The District of Columbia was in many ways a different city when Rayful Edmond III was sentenced to life without parole in 1990. The drug lord, who reportedly controlled a fifth of the city’s crack cocaine market, was arrested the year before, when DC suffered 434 homicides and Edmond’s home turf of Orleans and Morton places, Northeast, wasn’t close to luxury apartment buildings, an REI, and one’s choice of upscale grocery stores and gourmet eateries.

But it’s Washingtonians who will help a judge decide whether Edmond should be released from prison. Here’s a quick primer on who Edmond is, and why his freedom is not an easy question.

An early start in the drug trade

Edmond was “among the first of a new breed of drug dealers,” Harry Jaffe and Tom Sherwood wrote in their book Dream City. His parents both reportedly sold drugs, but they were small-timers compared to their son, who took advantage of cocaine’s entry into the local market and a DC police force reduced by what Jaffe and Sherwood call the “studied neglect” of Marion Barry’s administration. The cocaine trade was much more violent than what authorities had seen in markets for other drugs. Edmond and his crew “used intimidation and violence to protect their business,” prosecutors says; he was personally never tied to a homicide, but his enforcers were linked to 30 murders.

Conspicuous success

Edmond’s operation reportedly made hundreds of millions of dollars a year at its peak. He was a high-roller at big boxing matches in Las Vegas and Atlantic City and went on epic shopping sprees in Georgetown and New York. His Jaguar’s hubcaps had gold inlays. Edmond’s crew also pursued a Robin Hood image in his neighborhood. Tony Lewis Jr.‘s father was a top associate of Edmond; he writes in his excellent autobiography, Slugg, that he once saw Edmond win $10,000 at craps and throw it in the air so people in the neighborhood could pick up whatever they could. In DC, Lewis writes, “Kids knew more about Rayful than they did about Martin Luther King, Jr.” As Jaffe and Sherwood write:

He’d make sure neighbors had turkeys on Thanksgiving; he bought meals for the homeless, cars for his top staff, and clothes for his friends. He sponsored a basketball team in the Police Athletic League called “Clean Sweep,” the name of the police operation designed to get drug dealers off the streets.

The John Thompson story

Edmond was a huge fan of Georgetown University basketball and often sat courtside for games. He grew up with John Turner and attempted to befriend Alonzo Mourning. Legendary Georgetown coach John Thompson called Edmond in for a meeting and, according to the Washington Post, “lit into him.” The story continues:

He told the drug dealer to stay away from his players or suffer the consequences. Edmond, it was said, never associated with a Georgetown player again.

The Colombian connection

Edmond’s operation was moving so much product that he caught the attention of Melvin Butler, a gangster from Los Angeles with a connection to the Cali cartel. He and Lewis “allegedly imported more cocaine into Washington than any drug dealers in the city’s history,” the Washington Post reported in 1990. When crack hit DC in 1986, Edmond’s operation was able to immediately take advantage of the new market. (“But for the way he was raised and permitted to grow in our society, [he] could be running a major American corporation,” one of his attorneys once said.) Other crews, notably Jamaican gangs, pursued a large piece of the DC market, but Edmond was able to hold onto his turf.

The end, Part 1

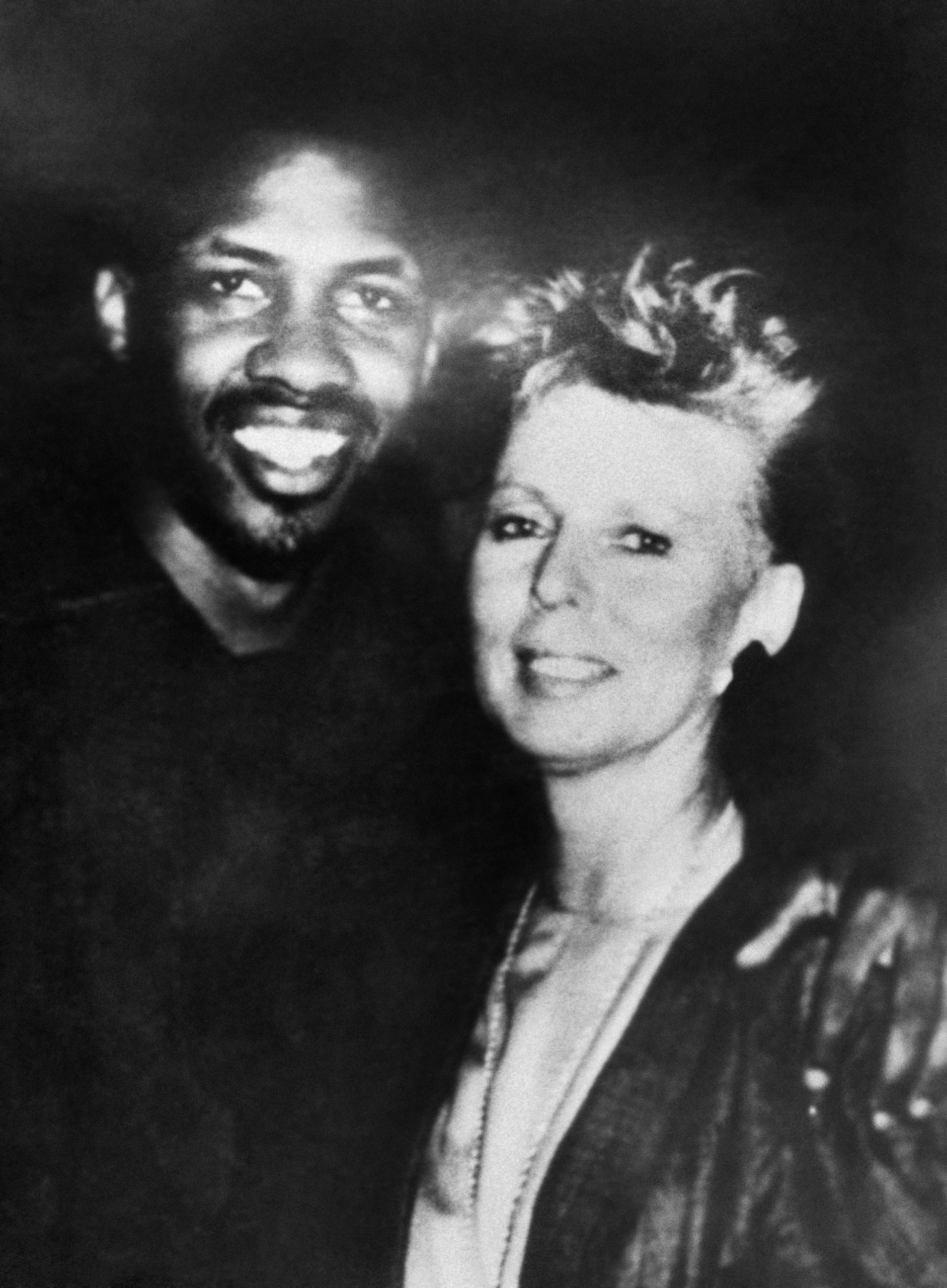

Edmond was arrested as part of a huge sting in April 1989 that snared 28 people—associates and family members. A girlfriend, Alta Rae Zanville, had worn a wire for months and recorded incriminating evidence of him, his coworkers, and his mother. He was convicted that December and sentenced to life in prison, but he predicted to Juan Williams the following June that he would spend perhaps two years behind bars. He also claimed that he never sold drugs. Regarding the reporter’s tape recorder, he explained his theory of non-involvement this way:

“Say like you want to buy another tape recorder,” he begins. “So I say, ‘Well, I know a guy who is selling tape recorders and he can give you a good price.’ So I tell you about him. I ain’t got nothing to do with it. I’m just telling you that I know the guy . . . Whatever y’all do is y’all’s business.”

The end, Part 2

This novel interpretation failed to sway the legal system, and Edmond was ordered to serve his sentence at a federal prison in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. There, the government says, he connected with Colombian traffickers incarcerated in the same prison, and Edmonds “facilitated narcotics transactions between associates of those Colombian drug traffickers and the defendant’s associates in Washington, D.C.” When caught in 1994, he pleaded guilty but agreed to turn informer in return for his mother’s release. He was sentenced to an additional 30 years.

The informer

Edmond’s deal with the federal government was immediately productive. He testified or agreed to testify in nine trafficking cases, participated in a sting operation that the feds say “resulted in the seizure of $190,000 in drug proceeds and convictions of eight defendants.” He also helped authorities solve two murders that happened in the prison. After his mother’s release in 1998, Edmond continued to cooperate, testifying in drug cases, providing intelligence for drug investigations that the government says led to more than 100 arrests of dealers, contributing information to homicide cold cases, and contributing to prison reforms. From the government’s motion to reduce his sentence:

Last, defendant’s drug trafficking operation conducted from inside USP Lewisburg precipitated a Department of Justice Inspector General’s (“IG”) investigation into telephone usage and visitation privileges afforded inmates by the Bureau of Prisons (“BOP”). The defendant spent hours explaining to IG officials how he and other inmates had exploited their prison telephone privileges for criminal purposes. Ultimately, the BOP completely revamped the inmate telephone system, eliminating inmates’ ability to make three way/conference calls and long distance calls. Going forward, inmates were restricted to calling only preapproved telephone numbers that have been vetted by BOP and other law enforcement officials.

What happens now?

A US District judge has ordered public forums to discuss the possibility of Edmond’s release. Two have been held so far. People can also leave comments via a website. “The defendant is 54 years old, and he has been incarcerated since April 15, 1989 – almost thirty years,” the government writes in its motion. The Washington Post reports Edmond is in the witness protection program while in prison and would continue in the program if released. The point may be moot: Pennsylvania prosecutors would have to agree to reduce his additional 30-year sentence.