It was just past midnight on a Thursday when I started zapping the apps. I was halfway through a bottle of wine, a bit giddy, methodically deleting all the little icons that have basically come to dominate my waking life. Goodbye, Twitter. See you later, Instagram and Facebook. So long, Wordscapes, YouTube, Netflix, Hulu, HBO GO, and—deep breath—Spotify.

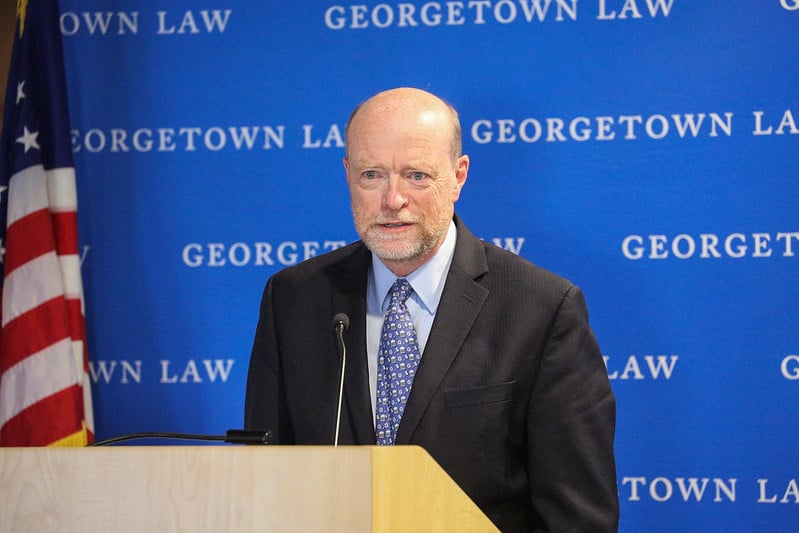

Why was I blowing up my entire online life? Because Cal Newport said I had a problem. The Georgetown University computer-science professor’s latest book, Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World, argues for an aggressive rethinking of our tech habits and lays out ways to fundamentally change one’s digital existence.

I’d read this kind of stuff before, of course. A library’s worth of books and articles promise practical advice to improve productivity and streamline your digital environment. But Newport—who has a doctorate from MIT—is taking a deeper approach, developing what he calls a “full-fledged philosophy of technology use rooted in your deep values.” His advice isn’t just theoretical. Before writing the book, he enlisted 1,600 people to try out his methods, which helped him refine his ideas.

When I recently read Digital Minimalism, I had to admit that I recognized a lot of myself in his criticisms of modern online life. Could the techniques that apparently worked for most of his test subjects also help me?

So I decided to ask him for help. Now here I was, putting his advice into practice, slightly tipsy and more than a little anxious about how I was going to handle my long-distance relationship, busy digital-media job, and basic life needs without access to the tools that usually make it all possible. Finally, I was done with the purge. I hit Do Not Disturb on my phone and went to bed. The next day, things would be different.

Before I started the detox, Newport had invited me over to his Takoma Park home for some in-person tips. When I got there, he led me to a tidy office space that Marie Kondo might approve of. I told him I was nervous about the experiment. “You’re going to have great success with it,” he said. “It’ll change your life. A lot of these technologies are having a much bigger impact on people than they realize. This gives you a grounded, consistent way to make decisions about tech.”

That sounded good to me. The first step was to cut out everything digital—that was the detox period—then reintroduce only what truly improved my life, consuming it in manageable doses.

Newport doesn’t have any social-media footprint—a bit surprising for a 37-year-old computer geek promoting a book. “I made peace that I’m just weird,” he says.

Many of his ideas were inspired by Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, which he read in his twenties. “What Thoreau sought in his experiment at Walden was the ability to move back and forth between a state of solitude and a state of connection,” Newport writes. “He valued time alone with his thoughts—staring at ice—but he also valued companionship and intellectual stimulation.”

Ultimately, Newport told me, I should figure out which parts of my life involve “optional technologies”—ones not critical to my personal and professional needs—and reduce or eliminate them. Microwave, yes; Reddit, no. Google Maps, yes; Netflix, no. The detox period lets you reset and then reassess which technologies truly add value to your life.

I was planning to detox for only ten days, not the full month, but it still seemed daunting. After all, I hadn’t even been able to read Digital Minimalism without taking frequent breaks to play the new word-puzzle game on my phone and tweet about the Gentleman Jack finale.

Digital overload is a problem everywhere, but it’s especially acute in Washington, where events seem particularly consequential and big developments unfold not by the hour but by the second. Whether you work on the Hill or in a newsroom, today’s technology can get overwhelming. “It seems totally destructive for all of us and our relationships and the ability to connect with those around us, definitely,” says prominent political writer Olivia Nuzzi, who lately has been trying to cut back on Twitter, where she has 198,000 followers. “Part of it is the Trump effect. If you’re not online constantly, you might miss war with Iran or something.”

To Newport, much of this angst is just unnecessary. “There are a lot of people in this town in a self-imposed constant state of autonomic alert,” he says. “The way news is presented is trying to hit those triggers. It just completely frazzles people’s nervous systems. That’s definitely a DC problem.”

There’s a lot of truth in that, I have to admit. I’m a journalist, so I do need to keep up with what’s happening. But do I really have to be so hard-wired into the breaking-news cycle?

The answer is no, which I quickly learned when I dove into my detox. In addition to deleting Twitter and Facebook from my phone, I downloaded a content blocker for my work computer, which prevented me from obsessively checking my various newsfeeds. I still used e-mail and Slack, but I muted desktop notifications for both so I wouldn’t be distracted by constant pinging.

Thoreau walked to a pond and stared at it. That doesn’t sound very good to me; I’d rather look at Instagram.

What did I miss? Not much. Sarah Huckabee Sanders resigned, somebody tagged me in an unflattering photo on Instagram, and Meryl Streep confronted Nicole Kidman on Big Little Lies. But I did find myself struggling with an unusual predicament: free time.

I had followed Newport’s advice to include streaming apps in the detox, so I wasn’t able to fill my evenings with many of my usual distractions, such as watching Pose or The Bold Type. Instead, I tried to get excited about cleaning the apartment. Wiping dust off of my mirror offered a certain satisfaction, but—let’s be honest—I would have much preferred to be cackling at an episode of The Good Place.

I decided to start Celeste Ng’s Little Fires Everywhere, a novel I’d been meaning to pick up for months. I read it on the fire escape as the sun set. The sky was cotton-candy-colored and gorgeous. It was a lovely way to spend the evening—exactly the sort of thing Newport wanted me to experience. I couldn’t stop thinking about how perfect it would be for Instagram.

As the week progressed, I realized that one of the best parts of being on a digital detox is getting to tell people you’re on a digital detox. But this minor thrill soon wore off as I remembered that all the people to whom I was feeling superior got to pick up their phones in dull moments and find the vast internet at their fingertips. Being unplugged was hard.

On the fourth day, I stayed up late to finish Little Fires Everywhere. It had been months since I’d actually gotten to the end of a novel, and I definitely started to enjoy the sense of quiet and solitude that comes from detaching from the digital world. But I missed my old life.

So I decided to get a different perspective. I called up Jason Feifer, editor in chief of Entrepreneur magazine and host of a podcast called Pessimists Archive, which digs into how innovations we now take for granted—from umbrellas to cars to novels—used to be considered dangerous by technophobes. Whereas once reading fiction was thought to be frivolous or even harmful, “now we say, ‘Put down Insta and pick up the novel,’ ” Feifer told me. “These are all personal decisions. It’s not a question about technology. It’s a question about time. Spend your time however you see fit.”

In a way, that’s what Newport is saying, too. His idea is to ensure that your digital life is making you happier rather than more anxious and depressed. “Forget the ‘digital’ part,” he says. “The exciting thing about digital minimalism is what happens in people’s lives when they get back in touch with what they want to do.” Newport’s research suggests that for many people, tech is “bleeding away this energy of life,” and his solutions can make a real difference.

But I’m not so sure that’s the case for me. When I logged back in ten days later, I quickly ramped up to my old online self. Now I’m no longer quite as afraid of tech-free silence; I’m looking forward to more nights on the fire escape with a good novel. But mostly, I still plan to spend my time texting and tweeting and searching for that perfect Cardi B GIF reaction—not to mention closely following the news as it breaks in my various feeds.

In reality, I’m not some kind of helpless slave to digital culture. It’s just what I choose to do. And what about Thoreau and Walden and the power of silent contemplation? “Thoreau walked to a pond and stared at it,” Feifer told me. “That doesn’t sound very good to me; I’d rather look at Instagram. If you’d rather spend time staring at the pond, go stare at the pond. But that doesn’t mean that staring at the pond is better than staring at Instagram. We can’t put a value judgment on the way people spend their time.”

That sounds right to me. Which is why if anyone needs me, I’ll be watching Brooklyn Nine-Nine on Hulu. Feel free to reach out via text.

This article appears in the August 2019 issue of Washingtonian.