At the 2000 NFL owners’ meetings, 35-year-old neophyte Dan Snyder was excited to run into Leigh Steinberg, then the NFL’s most prominent agent. Steinberg was seeking a new deal for journeyman quarterback Jeff George. “We’re interested,” Snyder told the agent at the time, according to Steinberg.

Steinberg was perplexed. Washington already had a starter in Pro Bowler Brad Johnson, who had led the team to a playoff berth and first-round victory the previous season. Still, Snyder—while never telling then-coach Norv Turner of his plans, according to Steinberg—persisted. Within weeks, George had signed a four-year, $18.25-million deal at age 32.

George would be a high-profile backup for one full season before his career ended and he became one of the most prominent free-agent busts in league history. Johnson left for Tampa Bay via free agency and would lead the Buccaneers to a Super Bowl victory—something our city hasn’t come close to since winning in 1992.

Twenty years after Snyder bought Washington’s NFL team, his impulsiveness is the defining characteristic of his torturous tenure, the one constant in the gradual decline of a local cultural institution.

The two-decade record is bad enough—41 games under .500 (139–180–1). Then there are the signings of George, Albert Haynesworth, Adam Archuleta, an aging Deion Sanders, and Antwan Randle-El—all acknowledged as five of the NFL’s worst free-agent acquisitions.

But it’s more than that. It’s the organizational tone-deafness that precipitated a 19-percent decline in attendance between 2017 and 2018, the reason why a once-proud fan base hardly shows up anymore. (Washington was third in NFL attendance the year Snyder bought the team. Today it’s last, filling up just 74.4 percent of FedExField.)

It’s about cheerleader scandals. It’s about suing aging fans for defaulting on their season-ticket packages during a national recession. It’s about the hubris it takes to refuse to change the racial-slur name.

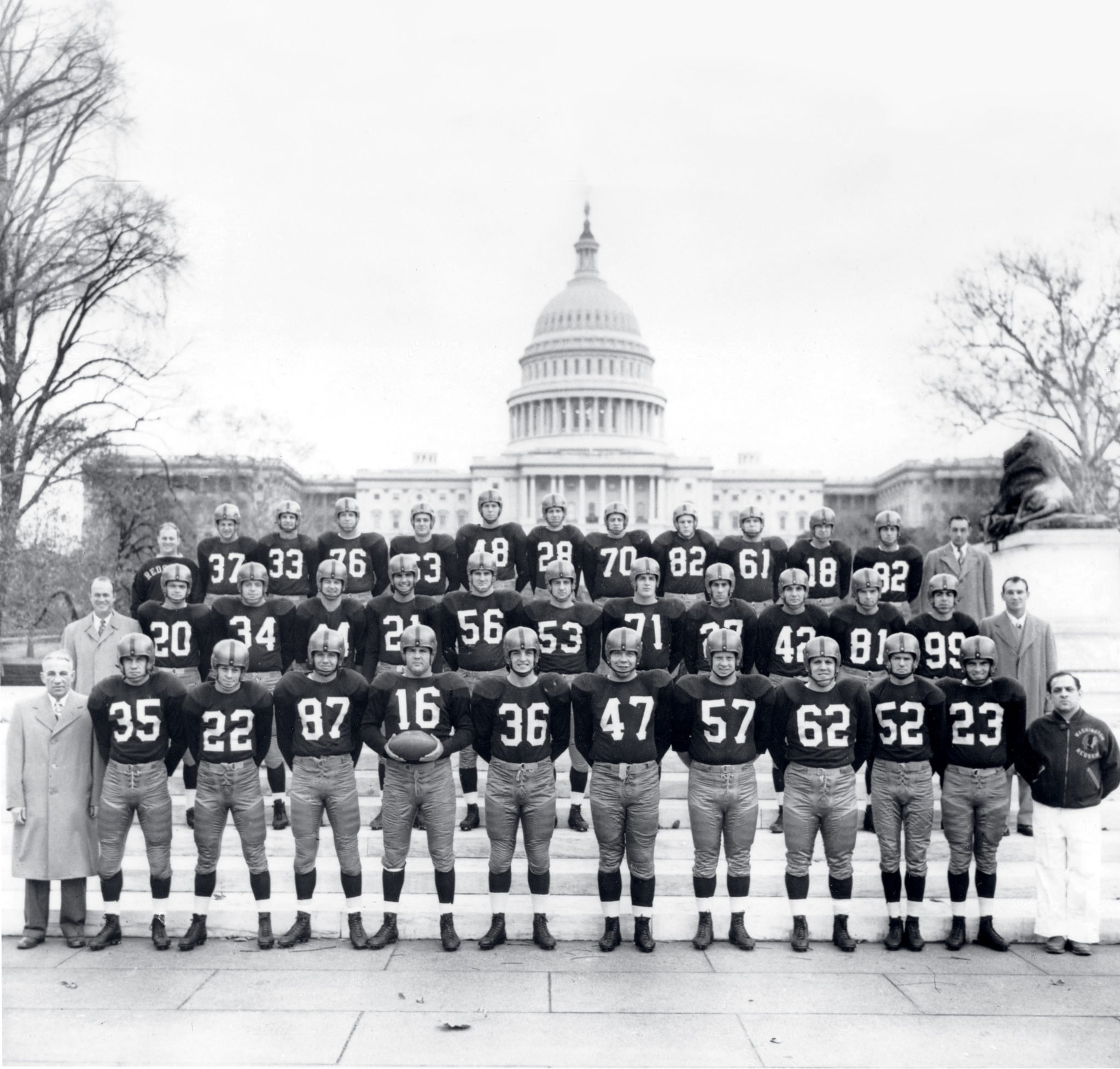

Anyone familiar with the team’s past knows that Snyder is not, despite the chaos, its worst owner. That would be George Preston Marshall, whose tenure ran from 1932 to 1969, when he died. Marshall is infamous for being an avowed segregationist who, along with former Bears owner George Halas, conspired to keep African American players out of the league in the 1930s and ’40s.

Marshall was the last owner to integrate his team, and that’s only because in 1961 Stewart Udall, John F. Kennedy’s Secretary of the Interior, threatened not to let them play on federal land, where DC Stadium—later renamed RFK—stood.

But as Snyder’s reputation has continued to plummet, Marshall’s afterlife has taken an unexpected turn. His granddaughter, Jordan Wright, writes regularly for the Native American news organization Indian Country Today. She wants the team’s name changed. And while Marshall’s will stated that not one penny of his fortune would go toward school integration, the George Preston Marshall Foundation is today known as an important provider of scholarships to needy children of all races in the Washington area.

About the only thing polarizing now is a memorial marker with his name and title outside RFK Stadium. (The DC Events authority is having a hard time giving it away; it needs to be moved at some point to accommodate redevelopment.)

All of which is just to say that legacies change over time, sometimes in unpredictable ways that have nothing to do with the person in question. That’s something that might comfort area football fans as they contemplate another season of low expectations.

This article appears in the September 2019 issue of Washingtonian.