Last fall, a demolition crew working on the new home of Studio Acting Conservatory in Columbia Heights made a startling discovery behind some drywall–an enormous frieze of the Last Supper sculpted by DC artist Akili Ron Anderson in the early 1980s and hidden after the building’s original occupant, New Home Baptist Church, moved to Maryland.

The participants in the Last Supper are African American, which reflects the influence of the Black Arts movement of the 1960s and ’70s on Anderson’s work at the time. He modeled many of the disciples on people he saw around New Home’s neighborhood, where he also grew up. “For me, and for the church at the time, the whole issue was to have their parishioners get comfortable with worshiping to an image that was similar to them,” he says.

Joy Zinoman, who founded both the Studio Acting Conservatory and Studio Theatre, hoped to find a new home for the piece, which is more than 21 feet wide and 10 feet high and anchored to the building’s cinderblock walls. Anderson did such a good job securing the sculpture to the building, in fact, that Zinoman says the best plan for taking it involved encasing the artwork in plaster, removing the entire section of the wall, and transporting it to its new home on a flatbed truck. The cost: between $800,000-$900,000, and maybe even more.

That plan, she says, was hatched by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, which made a number of visits to Zinoman’s building before deciding it could not acquire the artwork. It plans to clean the artwork and perform a 3-D scan of it, she says. Another potential new home for the work was Mother AME Zion Church, the oldest African American church in New York, which expressed interest in acquiring the frieze but whose budget, Zinoman says, was dwarfed by the cost of removing it. (Neither spokespeople for the museum, the Smithsonian, nor the pastor of Mother Zion have yet responded to requests for comment.)

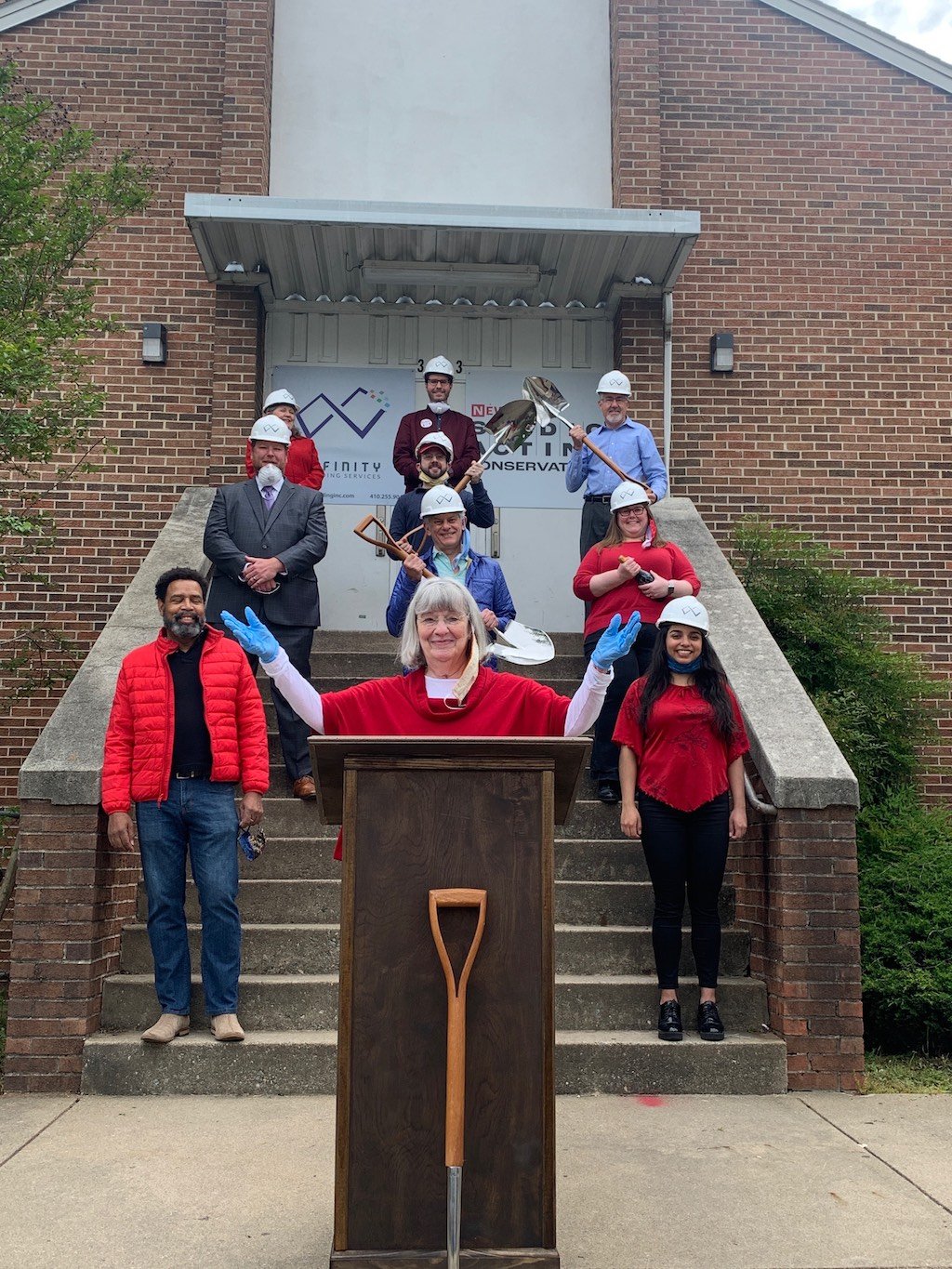

All of which is to say that on Tuesday morning, when the Studio Acting Conservatory holds its groundbreaking ceremony for the building on Holmead Place, Northwest, it will announce that the artwork will stay put. Zinoman was initially concerned that having such a prominent artwork on the walls of an acting studio could be distracting to students and teachers. Now she’s decided to install a heavy theatrical curtain in Studio B, on a track above it so it can be viewed as circumstances allow.

Studio Acting Conservatory held a well-attended open house this past January to show off the sculpture, and Zinoman says she hopes to open the studio often to people who wish to view the Last Supper. Anderson, a professor at Howard University whose stained glass works are visible around town, tells Washingtonian he’s been pleased with the response to the frieze’s discovery, which led to press in the US and abroad. “It’s good for an artist’s career!” he says.

Zinoman says she’d still consider finding a new home for the sculpture: “If at some later time somebody wants it and can take it, we’re still open to that.” Anderson says there’s more than one way to get it off the wall, and that anyone wishing to do so would have one great advantage: “Of course, the artist is still alive,” he says, “so the whole restoration could at least be supervised.” For now, he says, “Let’s see what happens, and maybe this will light a fire.”