About Coronavirus 2020

Washingtonian is keeping you up to date on the coronavirus around DC.

As lockdowns begin to lift across the country, Americans are anxiously wondering what the “new normal” is going to look like until we have a coronavirus vaccine. Designers at Gensler, a multinational design and architecture firm with a big DC presence, have been writing a lot about the future of design in the age of covid, and how to adapt workplaces for the new realities of life amid a pandemic.

This diary about what a typical workday looks like in China, penned by one of Gensler’s Beijing employees, Francois Chemier, is a fascinating scroll. Sure, we may not be primed to adopt all the movement-tracking features of a communist country, but the diary makes for a provocative thought experiment.

Here are some of the biggest takeaways from Chemier’s account:

Temperature Scans and Masks Are Everywhere

From the moment he steps out the door, Chemier must be wearing a mask. “If you forget it, the guards at the one remaining exit from your community will remind you and not let you leave until you wear one,” he writes. At the subway entrance, guards ensure he’s wearing a mask and take his temperature. And again when entering his office. And again at the restaurant where he gets lunch. And again when returning back home. “The body temperature scanning systems have been improved since the beginning of the outbreak—going from infrared thermometers to infrared cameras—allowing people to pass seamlessly,” Chemier writes. If you have a fever, guards will call an ambulance and take you to quarantine.

There’s an App to See How Crowded the Trains Are

Chemier is carless, so to get to work he has to choose between a rideshare bike, a cab, or public transportation. In some ways, the subway seems like the safest bet. The stations are completely disinfected every day, and passengers do their best to social distance. Chemier has an app that shows how many people are on arriving trains. “If the load is greater than 50%, I might wait for a less congested train to come along,” he writes.

Our Contact Tracing Looks Like Child’s Play

To enter many public buildings like offices and shopping centers, people need to have their personal “E-pass” badge scanned to ensure they don’t pose a risk of spreading the virus; the badges track their movements. In some cities, you need to enable an app that uses your location data to analyze where you’ve been in the past two months. “A green code indicates if you have been in Shanghai and have not traveled much, allowing you to access major malls, hospitals, and other public places,” Chemier writes. “A yellow code means you have been to potentially compromising areas that might have exposed you to the virus. A red code denies access altogether, meaning you have likely been in a place at the same time as a sick person.”

There’s No A/C

Beijing is even hotter than DC right now, but Chemier’s office isn’t allowed to use the A/C or central ventilation, and all of the windows are open. He doesn’t explicitly state why, but this is likely to improve air circulation and reduce the risk of spreading the virus through airborne particles. “It quickly becomes hot in the afternoon, especially with the mask, and turns cold at night when we work overtime,” he writes.

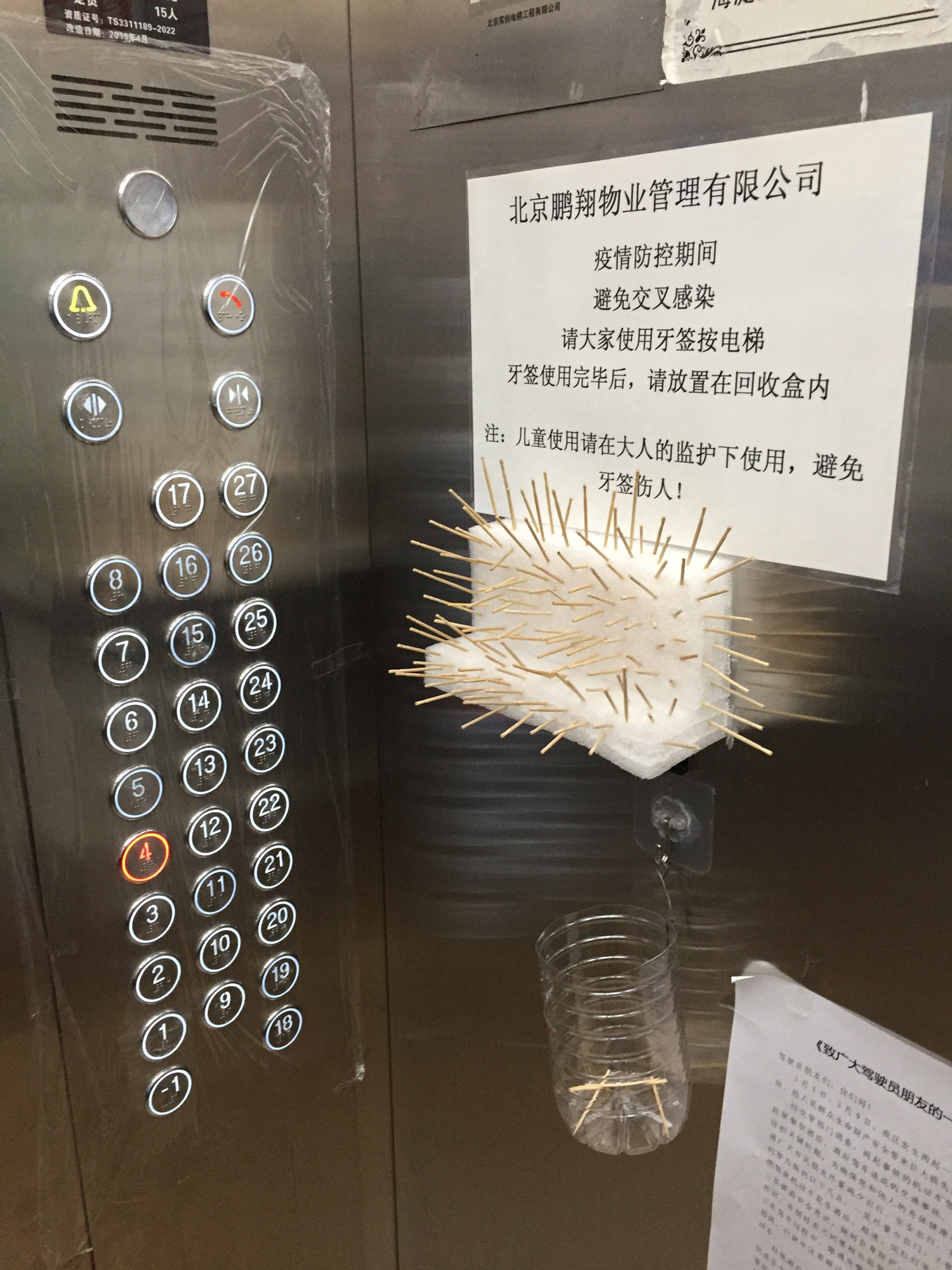

Even Elevators Are Jerry-Rigged for Social Distancing

In Chemier’s office, elevator capacity has been reduced from a 16-person to a 5-person maximum. The elevator cabs are cleaned with frequency and disinfected every day, and there are red markings on the floor of the elevator lobby to ensure people stay at least a meter apart while they wait. Things are even more intense in the elevator at Chemier’s apartment building. Management stuck a bunch of toothpicks into foam for people to use to touch the buttons—there’s a little waste-bin for people to dispose of the button-pushers once they’re done. “The sight of it makes me think of a hedgehog—and always brings a smile,” Chemier writes.

Getting Lunch Is an Ordeal

As mentioned before, all of the restaurants and supermarkets are taking temperatures, but that’s just one hurdle Chemier has to jump to get food. “Some places have free disinfectant and some don’t,” he writes. “Half of the seats have been removed to maintain social distancing, and the number of people per table has been cut in half. Not sitting in front of each other is the rule, but it isn’t always respected.” To get back to the office, he has to get his temperature scanned again, show his E-pass, wash his hands, and disinfect them again after opening the door.

To read the full day-in-the-life diary from Gensler, click here.