Tewodros Aklilu had basically forgotten about the album that he and some friends self-released back when he was a young man living in DC in the ’80s. He didn’t realize that the super-obscure record, Sons of Ethiopia, had somehow found a following among collectors, who paid big money for rare copies. And he had no clue that a Danish guy named Andreas Vingaard, who lives in New York and runs a tiny reissue label, had become fascinated by the album and wanted to bring it to a new audience.

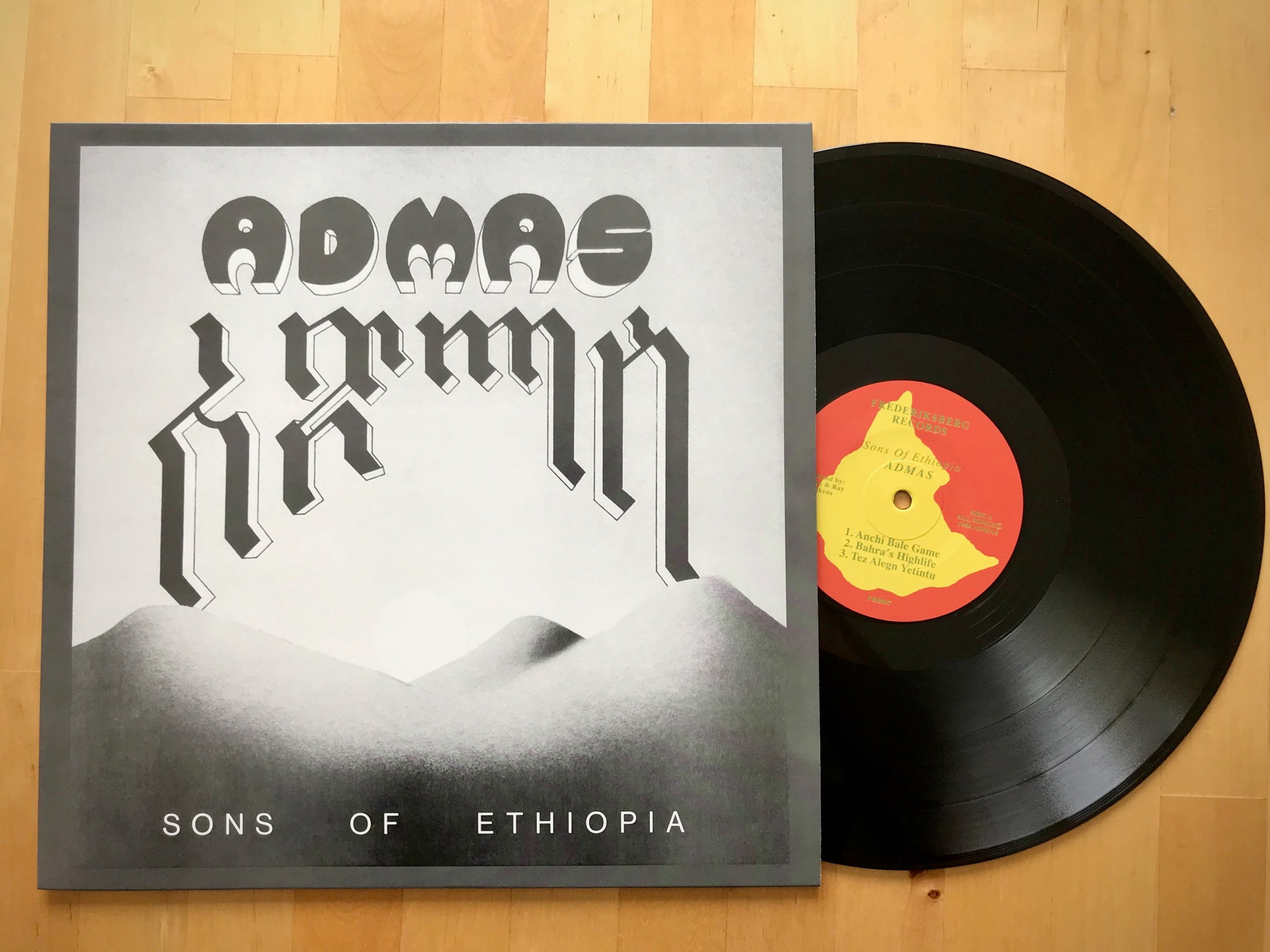

So when Aklilu heard from Vingaard on Facebook one day, he was more or less flabbergasted. “It was completely unexpected,” says Aklilu, talking on the phone from Addis Ababa, where he has lived for the last decade after spending 40 years in the US. “I had no clue. Zero.” Now Vingaard’s label, Frederiksberg Records, has released Sons of Ethiopia as a lovingly packaged vinyl reissue, complete with elaborate liner notes.

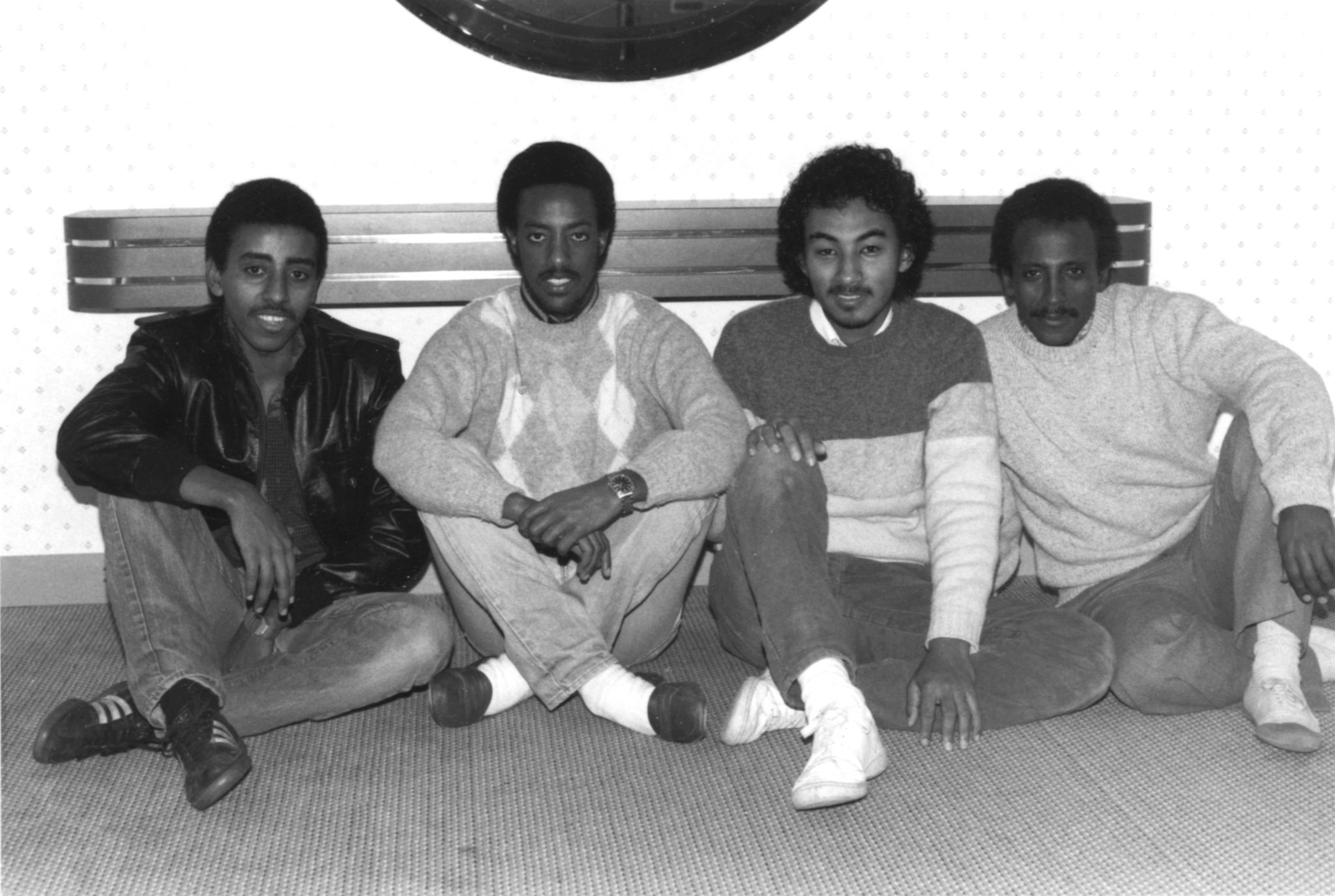

In the early ’80s, the band—known as Admas—played weekend gigs at Red Sea restaurant in Adams Morgan, setting up after the dinner rush and performing sweaty sets that went until 2 or 3 in the morning. Core members Aklilu, Abegasu Shiota, Henock Temesgen, and Yosef Tesfaye were mostly just having fun. “There was no career ambition, really, at that time,” says Aklilu, who back then was a full-time student at George Washington University and worked as a parking-lot attendant. “Everybody was doing something else. Being a musician was not rewarding financially. Our parents were discouraging us from doing it. So that’s what we were facing. But the audience was beautiful. It was a packed house.”

A synth-heavy mix of jazz, funk, Ethiopian music, reggae, and other sounds, Sons of Ethiopia came about by happenstance. Shiota wanted to learn about music production, so he rented a four-track tape recorder to play around with. “We had no intention of making an album,” says Aklilu. “We were experimenting, recording every day. And after about eight songs, we said, ‘We have an LP!’ We checked how we could make a record, and it was easier than we thought. So we went for it.”

A synth-heavy mix of jazz, funk, Ethiopian music, reggae, and other sounds, Sons of Ethiopia came about by happenstance. Shiota wanted to learn about music production, so he rented a four-track tape recorder to play around with. “We had no intention of making an album,” says Aklilu. “We were experimenting, recording every day. And after about eight songs, we said, ‘We have an LP!’ We checked how we could make a record, and it was easier than we thought. So we went for it.”

Aklilu borrowed $2,000 from his mother, a sum that paid for 1,000 copies of the album. “And if it was successful,” he says, “we were going to make more.” That proved unnecessary. Aklilu estimates they distributed about 800 of them, and then “we just kind of forgot about it, really.” None of the band members even owns an original copy, Aklilu says.

Vingaard, a passionate record collector, had heard about the Admas album after getting deep into Ethiopian music as a result of the popular reissue series Éthiopiques. A video journalist by trade, he started calling up key musicians from those classic records just to learn more. That led him to DC, which had seen a huge influx of Ethiopians in the wake of the 1974 coup that overthrew Haile Selassie. Vingaard tracked down Hailu Mergia and Moges Habte from the revered Walias Band, who have lived in Washington since the ’80s. (Aklilu says Habte was an important mentor to him.) Sons of Ethiopia fit perfectly into Vingaard’s areas of interest. Copies were hard to come by, but eventually he bought one on eBay for about $400. “The Admas record is an amazing testament to Ethiopian music,” he says, “but also to the multicultural potpourri of Washington, DC.”

After Sons of Ethiopia came out in 1984, most of the band members built careers in music. Aklilu has jazz and reggae bands in Addis Ababa, but his main gig is performing with Teddy Afro, a major Ethiopian pop star. Shiota has become one of Ethiopia’s top record producers, while Temesgen is a prominent music educator. (Neither Vingaard nor the group has been able to locate Tesfaye, the band’s drummer.) Now Aklilu, Shiota, and Temesgen are talking about recording new music together and, Covid permitting, going out on tour.

Asked why Sons of Ethiopia is finding new audiences all these years later, Aklilu speculates, modestly, that homebound music fans are starved for new recordings. Or maybe, it’s suggested to him, the album is simply good music? “It is good music!” he says. “I really think so. We put all of our hearts in it.”