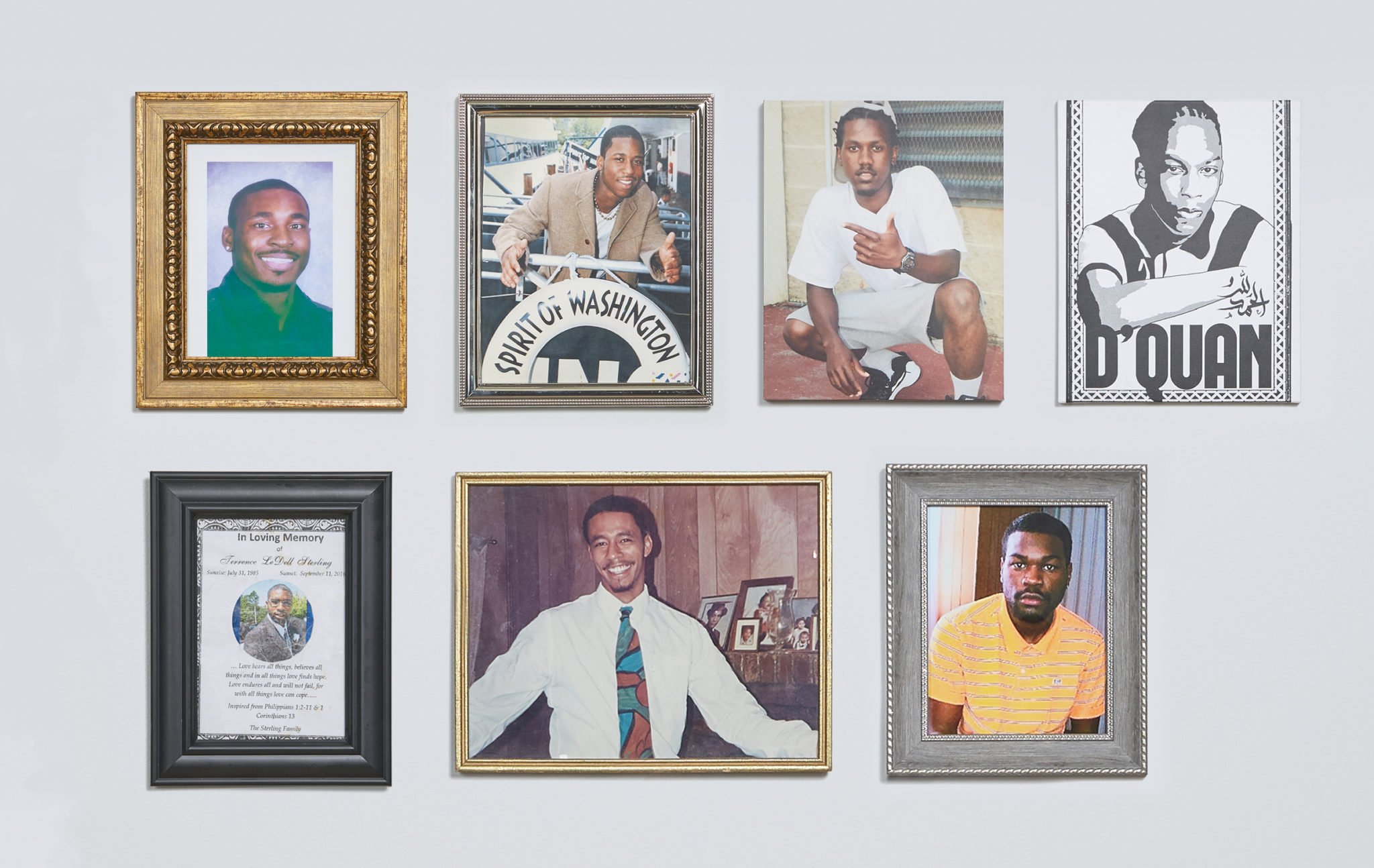

Over the past five years, police have killed more than two dozen Black Washingtonians. None of their deaths garnered the attention of Breonna Taylor, Michael Brown, or George Floyd. And yet—police killings of African Americans in Washington go back decades, brutalizing those left behind, who have searched for answers they suspect would have come easily to white residents. Today, though, amid a national reckoning around police violence, some of these loved ones have renewed hope that even as they’ve had to relive their personal traumas, this time it may not be in vain. Here, seven families spotlight the lives they lost and their quests for justice.

Archie “Artie” Elliott III

December 8, 1968–June 18, 1993

Age: 24

Manner of death: Shot 14 times while handcuffed and seat-belted

Artie Elliott was driving home from his construction job when a District Heights police officer named Jason Leavitt pulled him over. According to media reports and court records, Elliott failed sobriety tests and admitted he’d been drinking. Leavitt handcuffed him and called for backup. A Prince George’s County officer, Wayne Cheney, arrived. They strapped Elliott into the front seat of a cruiser. The officers said they were talking by the passenger side when Elliott pointed a handgun at them from behind the closed window. Leavitt alleged that Elliott didn’t comply when he ordered him to drop the weapon. The officers fired 22 rounds, hitting Elliott 14 times.

An internal police investigation exonerated both officers, and a grand jury determined that there wasn’t enough evidence of wrongdoing to criminally indict them. Yet Dorothy Copp Elliott, Artie’s mother, is haunted by questions: How is it possible that Leavitt didn’t find the gun on her son—who wasn’t wearing a shirt—when he searched Artie? How did Artie manage to retrieve the weapon and point it while drunk and handcuffed?

The family filed a federal excessive-force lawsuit that was ultimately dismissed when an appeals court determined that Elliott had threatened officers, and thus deadly force was justified. Elliott and her ex-husband, who was then a state judge in Virginia, tried to appeal to the US Supreme Court, which refused the case. So Elliott protested. For 22 consecutive Wednesdays, she and other demonstrators blocked access to the Upper Marlboro courthouse. Once, Martin Luther King III, the civil-rights leader’s eldest son, showed up to take part.

Elliott, a teacher turned real-estate agent, wonders what would have happened if her son had been stopped in the age of cell-phone video. Even so, she’s feeling more encouraged than she has in a long while. After the police killing of George Floyd, an old MoveOn.org petition to get Artie’s case reexamined gained new traction. The State’s Attorney has agreed to review whether the case should be reopened.

“My son wasn’t a statistic—he lived for 24 years,” says Elliott. “I can just imagine what his future may have been like, his getting married and having children. He was going to build me a house.”

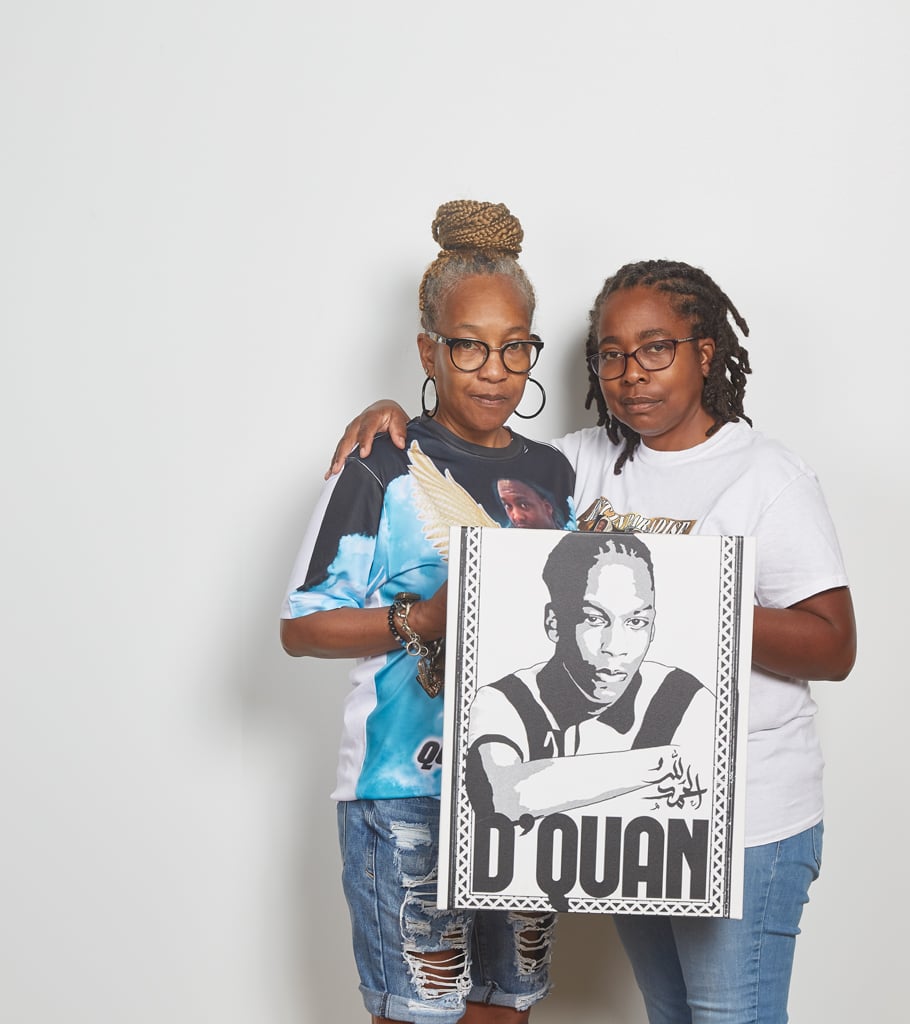

D’Quan Young

October 14, 1993–May 9, 2018

Age: 24

Manner of death: Shot five times

D’Quan Young died outside the Brentwood Recreation Center in Northeast DC. His killer was an off-duty cop. The Metropolitan Police Department has said that Young confronted the officer, who was on his way to a party nearby, and the confrontation escalated to a firefight. Police have not determined who fired first. Young was shot five times. Prosecutors declined to press charges, saying they couldn’t prove that the officer hadn’t been acting in self-defense. The officer returned to work. (He subsequently left the agency in 2019.)

D’Quan’s mother, Catherine Young, had sped to the rec center when word of the shooting reached her, but D’Quan’s body was already gone. She saw police tape strung everywhere, her son’s clothes and blood in the street. “It was just a nightmare,” says Young, a clerk at DC Superior Court. According to his autopsy report, three of the five shots struck D’Quan from the back, suggesting he was running away at some point. Young filed a public-records request asking for video that prosecutors said they’d reviewed, but she was denied. In July, just before releasing the video publicly, officials invited her to view it.

The surveillance-camera footage has no audio and was recorded from a distance. It appears to show D’Quan backing away as the cop shoots. D’Quan is obscured by a parked car, so it’s impossible to see whether he’s armed. Police say they found a gun at the scene with his DNA on it as well as a spent shell casing from the weapon. Through Young’s eyes, the video shows that the police officer was the aggressor. “He was going after my son,” she says. “My son was trying to get away.” Getting to see the video gave her no peace.

Relatives held a vigil on the first anniversary of D’Quan’s death, in hopes of keeping the pressure on law enforcement. This year, though, they marked the day in private. “It’s a strain on you to do all of that stuff,” says Young. The family is still considering whether to bring a lawsuit against the city. Michelle Young, D’Quan’s aunt, says friends and relatives wonder why they’ve held off so far. “The system is [supposed] to protect us,” she says. “Why should we have to sue?’’

Marqueese Alston

September 8, 1995–June 12, 2018

Age: 22

Manner of death: Shot at least six times

DC police officers were patrolling the Washington Highlands neighborhood when they came across Marqueese Alston, recently home from prison after a robbery conviction. The cops thought he had a firearm, according to statements by Metropolitan Police chief Peter Newsham. As they chased him down an alley, Newsham has said, Alston produced a gun and shot at them. Officers returned fire, killing him on the spot.

By early 2019, both the MPD and the US Attorney’s Office for DC had decided not to take action against the officers.

Since her son’s death, Kenithia Alston, Marqueese’s mother, has pressed to see the body-camera video. Amid an outcry over the city’s refusal to release it and a new DC law that forces officials to make such footage public, Mayor Muriel Bowser released it in August. The footage shows police running down an alley and shooting. After Marqueese is down, one cop says, “You good?” to another officer, then says, “I watched him turn and shoot at you.” But the footage is so shaky and moves so quickly that a viewer can’t clearly see Marqueese or what took place leading up to his killing. Before the city published the video, it provided a zoomed-in still image of Marqueese running with an object that police say is a firearm, pointed at the ground.

Alston and her lawyers at Georgetown Law’s Civil Rights Clinic contend that the footage only raises more troubling questions.

In June, she filed a $100-million wrongful-death lawsuit laying out her theory that Marqueese wasn’t actually armed and that after police shot him, they “[hauled] him across the pavement by his hands and feet, placing him next to a gun they claim had been in his possession.” Marqueese’s autopsy report—showing he was shot six times—indicates he was hit in the head, back of the arm, upper back, buttocks, and thigh.

Why did police approach her son in the first place? Why did they shoot him so many times?

“Justice,” Alston says, “would be for us to know the truth.”

Alonzo Smith

January 2, 1988–November 1, 2015

Age: 27

Manner of death: Cardiac incident while pinned under an officer’s knee

Alonzo Smith was a teacher’s aide at Accotink Academy, a Virginia school for children with special needs, and planning to return to college for a degree in social work. His last Facebook photo was of himself in a classroom, captioned “I’m all in for these kids.” Two days later, authorities said, Smith was seen around 3:30 am running shirtless and shoeless at a Southeast DC apartment complex, yelling for help. Police stopped him in a stairwell. The officers were “special police”—contractors who are licensed to make arrests and, in many cases, carry guns but who aren’t subject to the same oversight as Metropolitan Police Department officers. The officers shackled Smith, and one pushed a knee into his back, according to body-camera footage of MPD personnel who arrived on the scene. Smith soon stopped breathing, and he died shortly after arriving at the hospital.

His mother, Beverly Smith, who lives a few minutes from where Alonzo was killed, says the MPD didn’t notify her for another 36 hours. More agonizing still, they shared little about what happened.

The medical examiner found cocaine in Alonzo’s system and determined that body compressions had contributed to cardiac failure. His death was ruled a homicide. But the US Attorney’s Office for DC concluded it couldn’t prove that the special police had criminal intent or used excessive force. They weren’t charged or publicly named.

Smith became an activist, pushing for more local restrictions on special police, of whom there are thousands in DC. She hasn’t been able to watch the video of George Floyd dying under an officer’s knee, like her only son. It was too much to learn that Floyd called out for his mother as he lay dying. “I often wonder: What were my son’s last words?” Smith says. “Did he cry out for me, too?”

Terrence Sterling

January 31, 1985–September 11, 2016

Age: 31

Manner of death: Shot twice

Terrence Sterling, an HVAC repairman, was on his motorcycle on U Street around 4:20 am when police saw him driving at “dangerous speeds—sometimes estimated at 100 miles per hour or more,” according to a statement from the US Attorney’s Office for DC. Police pursued him, then caught up at Third and M streets, Northwest, and blocked his path. MPD officer Brian Trainer tried to get out of the car, when Sterling “revved his motorcycle,” accelerated toward Trainer, and crashed into the cruiser. Trainer fired two rounds into Sterling’s right side and neck. A toxicology report later showed that Sterling’s blood alcohol level was twice the legal limit. He was unarmed.

Footage of the shooting doesn’t exist—in violation of MPD policy, Trainer, a white four-year veteran of the agency, didn’t turn on his body camera until Sterling was already on the ground, dying. After nearly a yearlong investigation, prosecutors determined there was insufficient evidence to charge Trainer for the killing.

But the MPD’s internal investigation found that its officer violated use-of-deadly-force protocols: Trainer’s life was not in danger, the agency concluded, thus the shooting was not justified. The investigation found that Sterling had been trying to maneuver his motorcycle around the cruiser, not intentionally collide with it. Trainer was subsequently fired, and the city settled a wrongful-death suit filed by Sterling’s family for $3.5 million.

“Not only do I have to live without him, I have to live with the fact that the person who killed him is free,” says Shanita Stagg, 37, a MedStar office supervisor and Sterling’s girlfriend of more than a year. She went to Trainer’s administrative hearing—a proceeding that was part of his firing. But she got little satisfaction watching the city make its case for terminating the officer. “It wasn’t enough,” she says. “Terrence will never come back.”

Ralphael Briscoe

November 21, 1992–April 26, 2011

Age: 18

Manner of death: Shot twice in the back

Ralphael Briscoe was outside an apartment building in Southeast DC on the afternoon that DC cop Chad Leo and several other officers approached him in their unmarked Ford Explorer. They were patrolling as part of a plainclothes gun-recovery unit often accused of doing “jump-outs”—confrontations that critics liken to stop-and-frisk and that they say amount to racial profiling. (The Metropolitan Police Department denies using such tactics.) Briscoe was talking on his phone, according to witnesses who testified in a civil wrongful-death suit. The officers asked him if he had any guns or drugs. He said no and started to walk, then run, away.

The police pursued him. Surveillance video, recorded by a pole-mounted city camera, shows the SUV gaining on him, then Briscoe crumpling to the ground. Leo, a white seven-year veteran of the force at the time, had shot Briscoe twice in the back. A crime-scene investigator found an inoperable BB gun nearby.

The MPD’s internal investigation determined that the shooting was justified because Leo said he thought Briscoe had pointed a real firearm at him. Prosecutors never brought criminal charges.

In the course of the wrongful-death suit, filed by Briscoe’s mother, Bridzette Lane, an alternate picture came into view. Though the surveillance video appears to show something in Briscoe’s right hand, it’s impossible to tell what it is. At trial in 2015, her lawyer argued that Briscoe had only been holding his cell phone and that the BB gun was planted. Curiously, the lawyer explained to the jury, the BB gun had no fingerprints on it.

In the end, the theory failed to sway the jurors, most of whom were white. Leo was cleared of wrongdoing in the lawsuit and later promoted to detective.

Lane, who works at the Department of Agriculture, says that right after her son’s death, she told her pastor she’d chosen to forgive the police officers: “But then, over the years and after the trial, I saw nothing happen [to them]. I hate them now. I hate Officer Leo, because he took my son from me. He didn’t have to.”

Gary Hopkins Jr.

June 5, 1980–November 27, 1999

Age: 19

Manner of death: Shot in the chest

On the last night of his life, Gary Hopkins Jr., a student at Prince George’s Community College, went to a dance at the West Lanham fire station, wearing his late father’s lizard-skin shoes. At the end of the evening, a fight broke out. According to Prince George’s County police, a tipster told them that someone in the car containing Hopkins and his friends had a gun—which was not true. Police confronted Hopkins. One officer drew his gun and, according to witnesses, held it to Hopkins’s head. At least nine witnesses said Hopkins put his hands up. Police said he grabbed the gun. A second officer, Brian Catlett, fired a fatal round into Hopkins’s chest.

In 2001, Catlett was put on trial for involuntary manslaughter and reckless endangerment. He waived his right to a jury, opting for a bench trial instead. A judge acquitted him, saying a defense expert convinced him that traces of Hopkins’s DNA were found on the gun.

Marion Gray-Hopkins, Gary’s mother, lost her son two weeks after her husband died of bone cancer. Twenty years later, she laments how “naive” she was at the time. The couple had raised their four kids in a middle-class neighborhood in Lanham, where they’d never previously feared police. She was an executive at Bank of America. But within a year of her son’s death, she was also an activist. By 2015, she had cofounded an anti-violence organization, the Coalition of Concerned Mothers. She also sits on the board of the ACLU of Maryland. “This is bigger than Gary,” she says, “and it’s bigger than any of these high-profile cases that you’ve seen. We’re talking about systemic racism and white supremacy.”

“The day my husband died, he said, ‘You know, you’re a soldier.’ That morning [before my son died], he said to me, ‘Dad was right—you’re such a soldier,’ ” Gray-Hopkins says. “I have to be a soldier, because they said I was.”

This article appeared in our September 2020 issue.