When you hear the phrase “CIA invention,” you probably think of trick briefcases, shoe phones, or cars that transform into submarines with a flick of your Rolex. But while the Agency has cooked up plenty of goofy spycraft gadgets (does the world really need a robot catfish?), it also has a history of contributing to technological innovations that have significantly impacted non–James Bond culture, including the lithium-ion batteries that power our phones and the technology that became Google Earth.

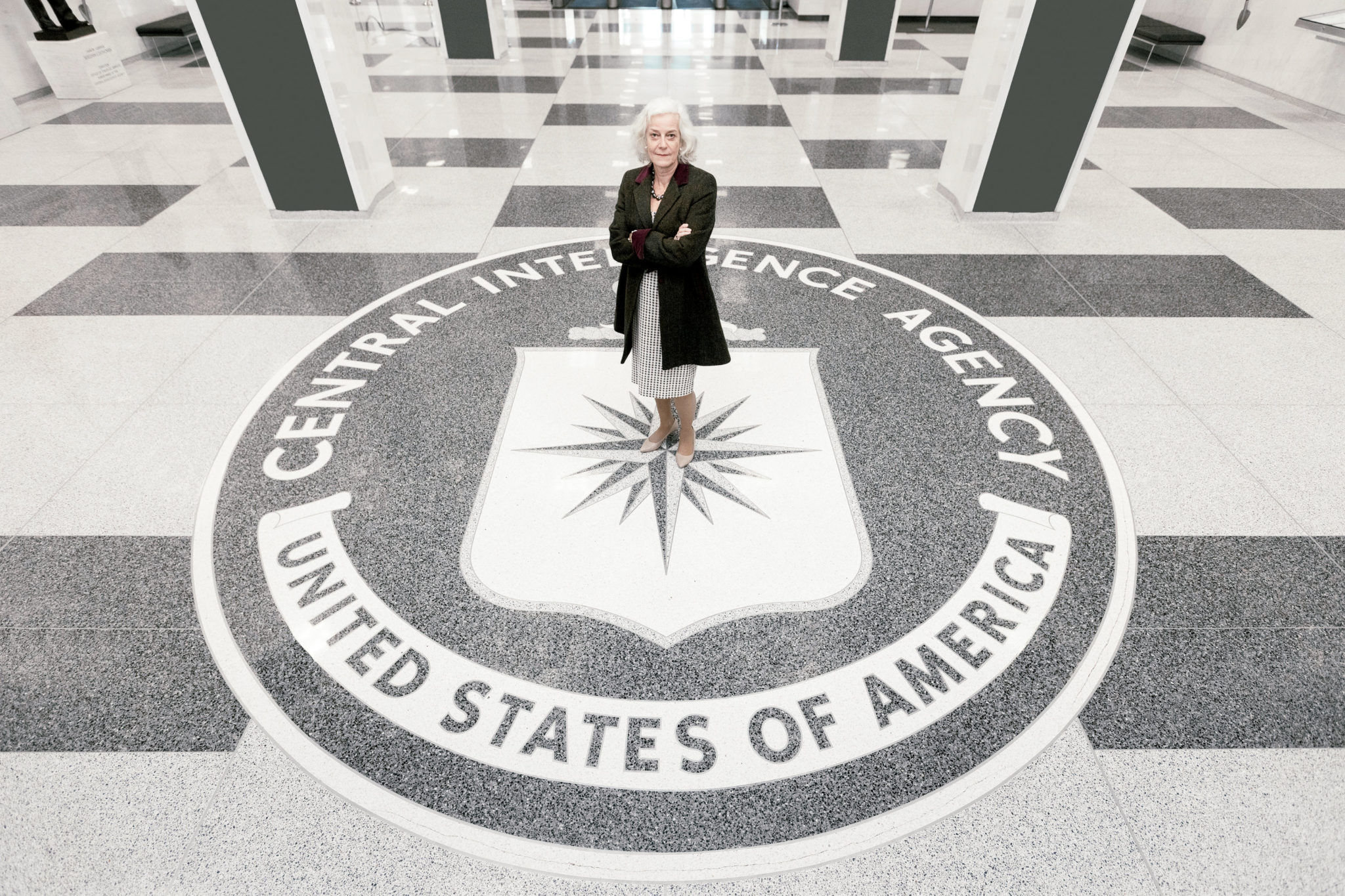

Now the CIA wants to bring more of its inventions to the public. In September, it launched CIA Labs, an incubator designed to cultivate tech projects—and make the CIA a little less insular. The concept was cooked up by Dawn Meyerriecks, the Agency’s deputy director for science and technology, a job roughly equivalent to that of “Q,” but without—we assume—people testing flamethrowing bagpipes outside her office.

Having previously worked at both AOL and the Defense Department, Meyerriecks has a deep appreciation for how innovation and technology are increasingly bringing the public and private sectors together. “We do everything from mascara to space,” she says, referring to the CIA’s efforts with conventional disguises and satellite-based snooping. “When we are asked to look at a national-security challenge, I can bring in, no kidding, experts from any discipline.”

Now CIA Labs intends to do the same in reverse—bring the Agency’s innovations to the outside world. Run by Meyerriecks from her office at Langley, CIA Labs is a resource for employees who have come up with original ideas during the course of their work. Meyerriecks’s team can help apply for patents and connect with experts for advice. Eventually, the plan is to partner with businesses that can bring ideas to the marketplace. Should profits ensue, the employee can personally earn up to $150,000.

The concept has already led to three patent applications, including one related to battery life. There’s a lot of untapped intellectual property at the CIA, Meyerriecks says, though getting inventions into the world has been a challenge for an agency so shrouded in secrecy. The hope is that there are overlapping interests with private industry and that each side can learn from the other. “It’s fundamentally a technology conversation,” she says. “There’s nothing spooky about it.”