Written over the course of 17 years, Morowa Yejidé‘s new book, Creatures of Passage, is set in Anacostia in 1977 and follows twins—one living, one dead—who share names with the Egyptian gods Nephthys and Osiris. But that barely hints at the richness and complexity of the book’s many strands. “The novel brings to mind the best of Toni Morrison,” George Pelecanos recently wrote in the Washington Post. “It’s that good.” We talked to Yejidé about her journey to write it and some of the big ideas she’s exploring.

This is a hard book to know how to talk about. How do you respond when people ask what it’s about?

It’s about a lot of things. Essentially, it’s a window into the unseen Washington, the Washington that usually does not get covered by the media. It’s a window into everyday people’s lives in a fantastical context, so to speak. The community itself comes together to save a young boy who sort of represents the future of that community.

There are a lot of books where a city is essentially a character, but that seems especially true here. What were you trying to capture about DC and Anacostia in particular?

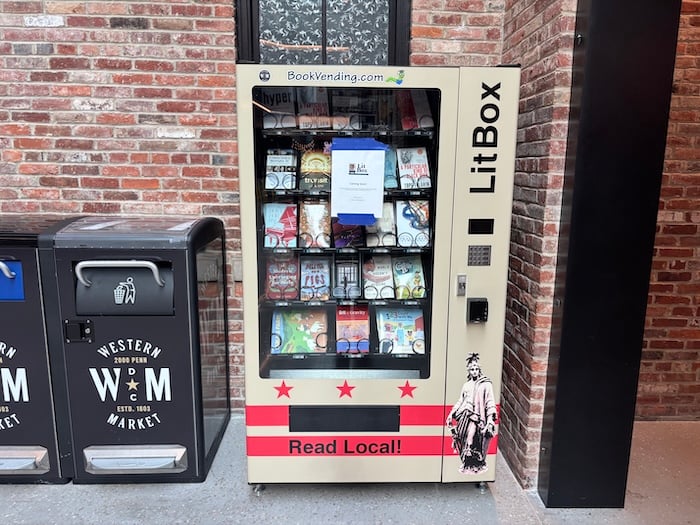

I really wanted people to know that beyond the government and the monolithic view we get of Washington, this is a very vibrant place where everyday people are living out their lives. They’re going from one generation to the next, dealing with one challenge or another. The city itself is unlike any other city in the country. The media has done a great job at giving a sense of, oh, this is a New York story or this is an LA story. I want to give a sense of what a Washington story can look like and feel like—from a Washingtonian’s point of view.

Your grandmother drove a cab in DC, and she was partially the inspiration for Nephthys, who ferries people around the city in her car. Tell me about how her experiences informed the book.

My grandmother in many ways was an extraordinary woman. I wondered about the people who got into her car, what their challenges were, and how she felt driving through the city, what it was like. She lived in a different era than I do, but of course many of the challenges remain from one year to the next, one generation to the next. It was the concept of her moving through time, me moving through time, and my sons—who are now college age—watching them move through this era. She was the spark of the idea of that sometimes the victory is in the ability to continue moving. For a lot of Washingtonians, particularly those in Anacostia, it’s not some great epiphany or magic bullet or magical situation that changes everything in their lives. It’s just the victory of insisting on moving forward.

The book took you 17 years to write, on and off, which means that the person who finished it inevitably wasn’t the same person who started it. What effect does that have on a book like this?

It sat collecting dust for many years. I set it aside to deal with life and enjoy life as a wife, as a mother. There were jobs in between, family responsibilities. So the story morphed with me—it changed with me throughout the years as I watched the city change. It grew up with my children. It was almost like another child in the family. [Laughs] Every once in a while we’d say, well, let’s, let’s see how it’s grown.

I don’t think I could have written Creatures of Passage as a younger writer, simply because it deals so much with gain and loss. As you get older and experience more of that, as I have, you get a sense of the longer view of things. As children grow and go off to college, you get a sense of the passing of time and how quickly it can go by, and also how permanent it is, how some things remain the same regardless of the year. Those were the types of things that informed my writing as I matured.

The parts of the book that deal with Nephthys in her car really capture what it’s like to drive around the city at night by yourself—that sort of surreal, dreamy state. Does that feeling have something to do with how the book came about?

It really does. A lot of places take on a different character and color and tone at night. Washington being such a majestic place, it doesn’t fail to mesmerize. I always thought there was a beautiful sort of magic that overtook the place at night and I was trying to capture that. Dawn as well.

I don’t want to get too abstract, but one of the things that I connected with most was this idea of porousness—all these boundaries that we think are impenetrable are actually kind of slippery: boundaries between life and death, the past and the present, the city and the people who live in it. Why does that idea appeal to you?

I think that fluid concept comes from my fascination with water, our most precious resource. It’s the most valuable thing; it’s what most of the planet is made of. It also represents the movement of time, and through one plane of existence to another in the story. I was trying to have a sense of the passage of time as a current—flowing like the river. If you could dip your hand in the water and stop everything, everything would be connected to everything else.

And then there’s the ripple effect: Something seemingly unimportant can many years later become enormous. Or a traumatic event in someone’s life can have long-reaching consequences. And also what happens to one generation is still felt throughout the decades by later generations.

Ghosts play a big role in the book. What makes the idea of ghosts meaningful to you?

I look at them as positive energies that were part of my family or part of my life. So even though my mother passed away, she’s still very close to me. My grandmother is still close to me, and others. It’s not like a ghost story where they follow you around the house and move things around. It’s more like what my mother said to me right before she died. She said, “You know, you carry me in your heart.” She put my hand on my chest and held her hand over top, and she said, “That’s where I’ll be.” That is probably what drove my writing of the ghosts—where they worry about their loved ones. Because in a way, [my mother] had one foot in this world and one foot in the next, and she was already concerned.

There are two kinds of ghosts in Creatures of Passage. There’s the ghost of Osiris, who is this core force in the book, but there’s also the ghost who lives in Nephthys’s trunk, who’s kind of literally baggage that she’s carrying around in the car.

Yeah, I always thought that would be an interesting element: Just as people have different experiences, ghosts would have different experiences, and their reasons for hanging around would be different. But ultimately, they all are charged with moving on. I mean, that’s what life requires, right? We have to move forward. We can’t go back. I was imagining what moving on might mean. Some are unable to move on, such as the girl in the trunk—just as people in this life are unable to move on. They kind of sit down on the curb of life. Things happen to them that break them. And I thought that could be true of a ghost.

I’m interested in the question of genre with this book. It’s obviously literary fiction and magical realism. But there’s also elements of fantasy, and it reminded me of some sci-fi books too. Is genre something you thought about as you were working on it?

I never thought about genre at all. Creatures of Passage to me is literary fiction. Having said that, it is polyrhythmic in many ways. It’s got magical-realism elements, it has horror elements. The sci-fi element, I see where you’re coming from with that, and I do enjoy sci-fi. That came from my fascination with cosmology, how the Big Bang Theory works and how the universe works. And I’ve always been an avid researcher and had a lot of interest in star formations and things like that. I was the nerd kid watching Nova as a middle-school and high-school student. Those elements add an interesting dimension; if you’re going to be scoping deep into someone’s thoughts, I also like to scope out as far as possible.

It’s not the subject matter that reminded me of sci-fi. I think it’s the way that the book creates a world that’s familiar and unfamiliar at the same time.

I see what you’re saying. I always enjoyed Isaac Asimov novels as a young person. Brave New World by Huxley I think is a masterpiece. Fahrenheit 451. Those types of stories do paint an alternate world, but that alternate world gives us a deeper view of the real world. That’s definitely something I was doing in Creatures of Passage. I’m just delighted that different communities of readers have found some interest in it.

This interview has been edited and condensed.