Kojo Nnamdi first hit the DC airwaves back when he was managing an activist bookstore. Now, a half century after starting his career at Howard University’s radio station covering the global Black diaspora, he’s retiring as host of a WAMU show that’s synonymous with hyper-local coverage. How did a young radical from Guyana become the guy we go to for reasonable conversation about area development controversies and transportation debates?

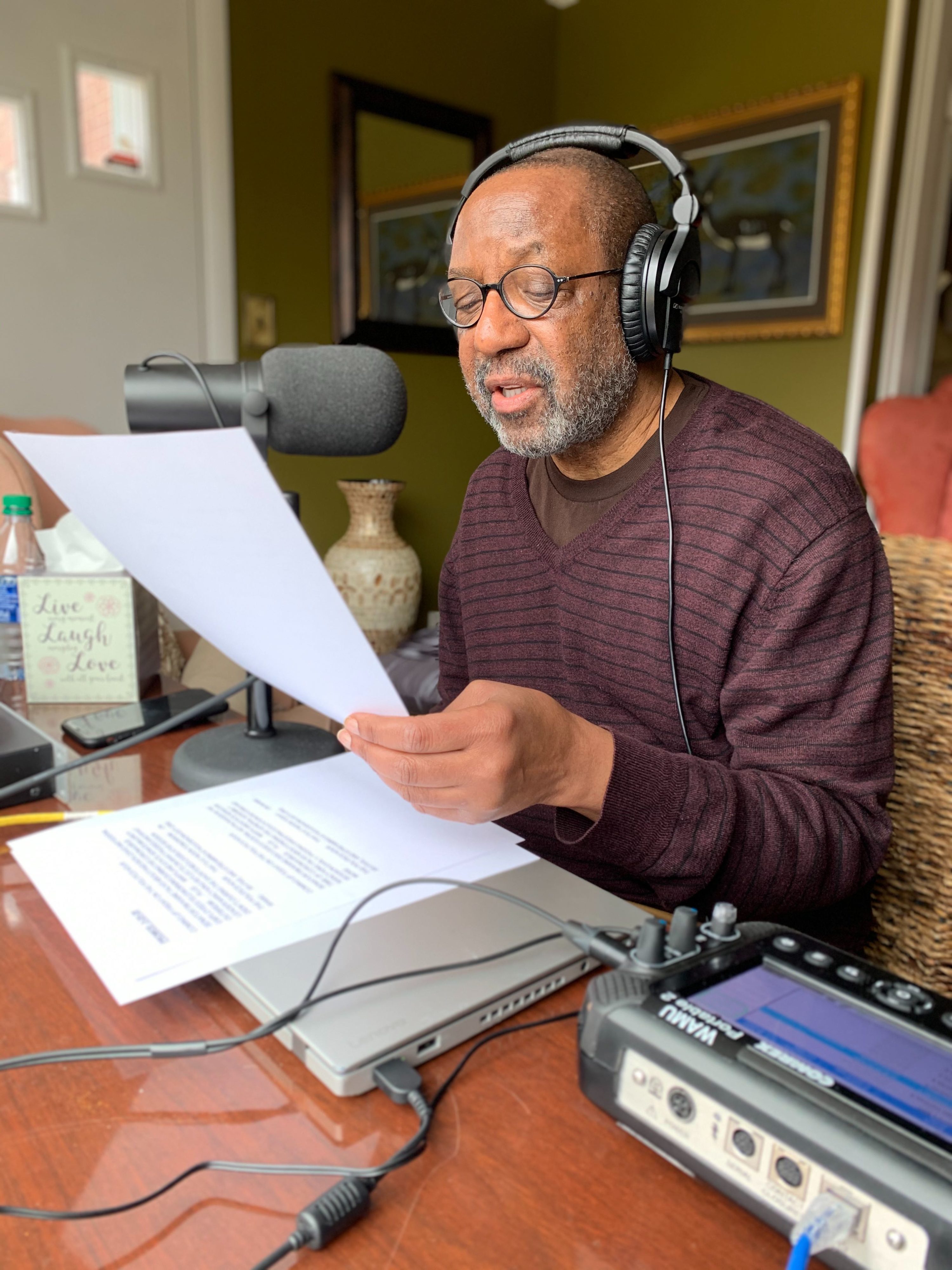

With The Kojo Nnamdi Show set to end in April (he’ll continue to host The Politics Hour on Fridays), the man formerly known as Rex Paul allowed us to turn the microphone around and interview him about the one Washington institution that’s rarely analyzed on the show: Nnamdi himself.

Interviewing Kojo Nnamdi is a little bit like making paella for José Andrés. How do you think I should start?

It’s all up to you. You’ve known me long enough to know what you want to ask me.

Well, when you’re sitting next to someone at a party, what do you say to start the conversation?

“Hi, my name is Kojo.”

Let’s start there, then. Kojo Nnamdi is one of the best-known names in Washington. But when you first moved here 52 years ago, you were this unknown young guy from Guyana named Rex Orville Montague Paul. Why did you come to DC?

I left Guyana in September of 1967 because I gained admission to McGill University in Montreal. My high-school friends from Guyana, who had become my roommates in Montreal, were all wildly enthusiastic about the Black Power movement. I got caught up in their enthusiasm. I went to New York in 1968 and promptly joined that chapter. But that was at a time when the Black Panther Party was beginning to fall apart. And I didn’t really want any part of that.

I learned from a cousin who lived in Washington that there was a Black-education program at what was then Federal City College. It seemed to me just the kind of thing that I would be interested in. As it turned out, the people who were establishing what became known as the Center for Black Education were many of the same people who had organized Black people to register to vote in the South. They were members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC. And those people quickly became my mentors.

Guyana was a British colony when you were a young man. It also is a place with very different demographics than the United States. And then you’re suddenly in the midst of politics in the American context, during this period of ferment. What sort of perspective did you bring that others may not have had?

There is a conservative intellectual who accused Barack Obama of pursuing his father’s anti-colonialist perspective. That was the perspective that I brought. I had left Guyana at a time in the 1960s when the anti-colonial movement was at its height. I grew up in a family that was, if not overtly political, definitely in the middle of all of the discussions that were taking place. And so when I arrived in Washington, I had some sense of people struggling against forms of oppression.

What was Washington like when you arrived in 1969?

The city was still devastated by the riots that followed the murder of Dr. King in 1968. Fourteenth Street was someplace that people could only tell me what it used to be like. There was still a seething resentment over not only what had happened to Dr. King, but in general the condition of Black people. But that was also accompanied by the rise in the Black Power movement. That injected a certain amount of pride in people. When I saw Black men in the streets in Washington, they almost invariably gave you the Black Power salute.

Was that different from New York?

Yes. And I was surprised about that. By 1969, [Washington] had become a Black-majority city, and so everyplace you went, you got these feelings of brotherhood and solidarity.

Where did you live?

The first place I lived was at 1447 Chapin Street, Northwest, in a large one-bedroom apartment, for which I paid $87.50 a month. If you were to go to that same address now—it’s right off Meridian Hill Park—you would not be able to get into that one-bedroom apartment for less than $2,000. And I thought $87.50 was a rip-off!

You got into media thinking about these enormous global things: the Black diaspora, Black power, nationalism, inter-nationalism. But your radio show has been focused on the most granular things—neighborhood issues, local government.

When I first started, WHUR, like much of the Black activist community at the time, had grandiose notions. The station slogan was “360 Degrees of Total Blackness.” And the newscast that I edited, called The Daily Drum, was noted because it covered the Black world. It wasn’t until I went to Howard University Television, hosting a show called Evening Exchange, that my local focus began to grow. Both of those jobs came at a time when DC was just getting home rule, when politicians like the Reverend Douglas Moore and Marion Barry—politicians who had had a history in kind of the Black-nationalist movement—were coming to power. They became fairly frequent guests. And so I became increasingly recognized for knowing what was going on locally.

And then Mark Plotkin [the former WAMU fixture, who died in 2019] asked if I would have a conversation with the program director at WAMU about cohosting the show called The Politics Hour. Long story short, I ended up hosting the entire ten hours a week of the show that was then called Public Interest.

When you took over, was there anything you thought you really wanted to accomplish?

Because I already had a full-time job at Howard University Television, there was no financial incentive for me to take this lower-paying radio job. But it occurred to me that up until that point, I had been working for a university-owned, predominantly Black station on one side of town and I was being invited to host a show at a university-owned, predominantly white radio station on the other side of town. One of the problems in Washington, both then and now, was the lack of racial equity and the racial divide, and I thought this would be a wonderful opportunity to create a dialogue between white and Black Washington.

In these 23 years, has there been a favorite subject for you?

Probably statehood. Well, statehood and Marion Barry.

What was it about Barry?

He was always a fascinating person to cover and interview. And he had caused such a fundamental change in the way business was done in this city by including a lot more Black people in contracting and in higher positions in the District of Columbia. People all across the country were looking at this—but looking at him, also, first as he matured and then as he began to fall apart. He and I had a kind of falling-out. I guess it was in 2010 and Vincent Gray was running for office, and I did an op-ed piece for the Washington Post saying that people should not be comparing Gray with disgraced mayors who had preceded him. Barry came on The Politics Hour and chewed me out. He said he used to know me when I was a revolutionary and look at what I have become now—a hack.

Any other issues?

I think race relations in this region, racial inequity in this region, and the region’s turn towards becoming more and more “progressive” has been fascinating to watch. When I first came here, there were a lot of people in Washington, Black and white, who wouldn’t even go to Virginia. Okay? It was “Oh, no, no, you don’t go to Virginia.” A lot of those people now live in Virginia. This whole concept now known as the DMV was really coming together.

Is there a dumbest issue that you’d be happy never to cover again?

Oh, I haven’t given that much thought.

Well, can I ask your opinion about the McMillan Reservoir?

See there—you had to bring that up.

Is it true that people from the McMillan activist group used to pretend to be calling about something else and then start talking about that when they got on the air?

I hadn’t realized they’d stopped! Yes, that issue drove a lot of people’s passions. Because on the one hand, you had what was a predominantly Black community in which people wanted the same access to the kinds of stores and eating establishments and all of the things that people in the more affluent wards of the city have. But at the same time, this neighborhood around the McMillan Reservoir was seeing the kind of gentrification which included a lot of people who are essentially environmentalists—who did not want to see this place being developed.

DC has changed so much since you’ve been doing the show—the demographic change, the economic change. What do you make of it? I mean, do you like this DC we live in?

When I came here, it was a majority-Black city. It now has a Black plurality, maybe 47 percent. But it’s still my city, and I still love it. And while I am concerned about gentrification and people being forced to move out of their homes and move to the suburbs, the suburbs are part of our demographic. And so I not only claim the city—now I claim the whole region.

You think we should be optimistic about DC? A lot of the economic inequality is shocking.

Yeah, but I look at the way activism has also risen in DC. When I got here, activism was limited to something called the United Black Front. When I look around now, I see a much more broadly based movement—a movement often led by African Americans but often including white people—in all parts of the region that understands the problems that have been caused by gentrification.

Don’t get me wrong—gentrification has also had some advantages in terms of the city’s coffers. But we have to take ownership of the places in which we live. We need to know exactly what our ANC is doing if we happen to live in the District of Columbia, what our school-board members are doing in Prince George’s or Montgomery County. I feel very hopeful about the future in that regard.

In the years since you’ve been doing the show, there’s been so much change in media across the country. You see local newspapers going out of business. Shows like yours are increasingly unique. Do you think Washingtonians are as well informed as we used to be? Or have as much access to local information?

No, we don’t. I think that one of the reasons our show has increasingly been a destination for people is because other destinations, frankly, are going away. And when people want to find out what is going on locally or hyper-locally, they are now forced to rely on very unreliable social media. One thing that bothers me is the disappearance of local and hyper-local media where people can rely on accurate information. There are a number of independent organizations being formed to try to make sure that there’s a level of investigative local journalism still taking place. But those organizations are themselves struggling, and I don’t see an easy way forward. I know there are a lot of people who are determined, and that is where my hope lies. Even as I am going into semiretirement, I intend to continue to try to support such ventures in every single way that I can.

Your own station went through an upheaval over equity last year. How did that land with you?

I became more keenly aware of it when I made a habit of going to lunch with younger and newer Black employees of WAMU and listening to some of their complaints. I obviously am in a privileged position at the station. But if we say that we want diversity, then we not only have to go out and hire people who bring the diversity into the workforce, but we have to hire more diverse managers. We were hiring a lot of diverse people but were not putting them in management positions. And ultimately, that blew up on us.

You launched your career from a Black-owned, Black-run environment. I wonder whether it would have been as possible outside that environment.

It’s more difficult. By the time I got to WAMU, I already had a reputation. But I realized how much more difficult it is for reporters who are just starting out and who are looking for guidance from management, and what they see instead are attitudes which suggest that they’re not competent. That’s what they used to complain to me about, and that’s what eventually led to almost an internal revolt at WAMU and resulted in the management losing their jobs. I think that’s going to be a very important lesson going forward.

So what are you going to do now? You have four new free days a week.

Catch my breath. I have a memoir in the back of my head. I’m thinking about doing more traveling once the pandemic allows.

Do you think you might become one of those people who call into WAMU at noon?

Whatever comes up, I’ll be available to call in and harass whoever is on the air.

This article appears in the April 2021 issue.