Read more from our Ultimate Guide to Cherry Blossoms here.

The idea didn’t come from the mayor of Tokyo.

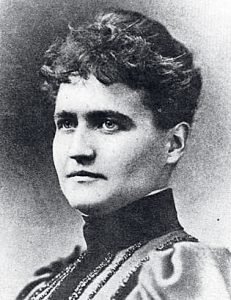

The story of how the cherry tree became the horticultural darling of our town actually begins with the National Geographic Society’s first female board member, travel writer Eliza Scidmore. She saw the famous trees in Tokyo in 1885 and vowed to bring them to the capital. It took two-plus decades, an ally at the federal government’s newly established Office of Foreign Seed and Plant Introduction, and some vigorous lobbying of the First Lady (Mrs. Taft), but by April 1909, 90 trees were ready to be planted along land running from the Lincoln Memorial southward. The public was soon enamored.

Before long, plans were under way for the city of Tokyo to give the US thousands of cherry trees, but almost immediately there was a problem. When the crop arrived in 1910, the USDA discovered that it was infested with foreign pests. No one wanted a diplomatic incident, but the agency saw no other solution than total destruction. So all 2,000 trees were collected into large pyres on the Mall and burned. Fortunately, the Japanese had a sense of humor about the mishap, the mayor of Tokyo joking, “Oh, I believe your first President set the example of destroying cherry trees, didn’t he?” Two years later, 3,020 replacements arrived—apparently pest-free. Washington had a new rite of spring.

It’s hard to believe, but over the next century, our beloved blossoms were threatened in all kinds of ways.

In 1938, when plans for the Jefferson Memorial called for removing trees along the Tidal Basin, a group of female activists (below) descended on the White House with petitions. They accosted workmen at the memorial grounds, wresting away their shovels. Some prepared to chain themselves to the trees. Outraged, President Roosevelt issued an ultimatum: The so-called Cherry Tree Rebellion should disband or its members and the trees would be uprooted. The protesters reluctantly relented.

WWII introduced a new menace.

Three days after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, vandals took a handsaw to four trees, writing TO HELL WITH THOSE JAPANESE on one stump. According to the Richmond Afro American, the act led to “talk of cutting [all] the trees down and re-placing them with an American variety” as angry patriots demanded that the trees be “torn up by the roots, chopped down, burned.” Instead, the National Park Service declared that the blossoms would become known as “Oriental” cherry trees. (The change was temporary; it lasted through the war.)

Decades passed without incident, but in 1999 trouble struck once again, this time in the form of toothy rodents.

The debacle began on April 3 when visitors to the Tidal Basin were stunned to find that a tree had been felled in full flower—its trunk gnawed through. A few nights later, four more trees became victims. The next night, another four voracious beaver terrorizes tidal basin, proclaimed the Washington Post.

The marauding animal became a sensation. Citizens took to the Tidal Basin with flashlights to patrol for the varmint themselves, and spectators from across the country hoped to catch sight of the furry villain. When a midsize female was caught, it seemed the ordeal was over. Then rangers trapped a small pup. Gah—the trees were feeding an entire family! Finally, on April 13—11 days and nine trees into the saga—a large male was taken into custody. All, at last, was well (though the Park Service never did disclose where it relocated its most wanted rodents).

The Tidal Basin has been spared serious endangerment since the funny beaver business of 1999—except, that is, from frost. Last year’s particularly harsh cold snap eliminated about half of the cherry-blossom buds and wreaked havoc on the peak-bloom schedule. Luckily, the only damage was to aesthetics, not the health of the trees. After all this time, Washington would wither without them.

This article appears in the April 2018 issue of Washingtonian.