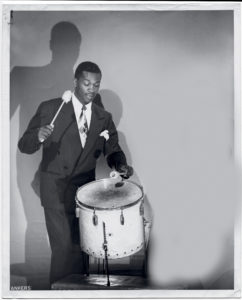

In the late ’70s, when he was a student at Georgetown University, Jay Bruder was assigned a term paper for a class in American history. Rather than drum up some new angle on, say, the Teapot Dome scandal, Bruder asked the professor if it would be okay to interview a local musician. Sure, the prof said. Bruder was a big fan of old R&B, so he decided to write about a singer, drummer, and bandleader named TNT Tribble, a well-known figure in DC’s bygone music scene. Bruder called up Tribble from his Georgetown dorm room. “ ‘Well, come on over Saturday afternoon,’ ” Bruder recalls Tribble telling him. “So I did.”

They met at Tribble’s house off of South Dakota Avenue in Northeast DC, and the two music fans hit it off. Bruder thinks he probably got an A minus on the paper. But what really mattered was that moment of connection to the past—to the music he’d come to love but couldn’t find nearly enough information about. “That’s what made me say, Okay, this guy has given us a lot,” Bruder says. “I need to make sure his story gets out there.”

Now, decades later, Bruder is making good on that promise. His old interview with Tribble was the start of years of research that went into a new doorstop box set titled R&B in D.C. 1940–1960, which Bruder spearheaded. It’s a huge undertaking: 16 CDs featuring 472 tracks, along with a 352-page hardcover book written by Bruder.

R&B in D.C. isn’t likely to be a massive seller; it has a price tag of more than $200, for one thing, and compact discs aren’t exactly in demand these days. But given the rarity of many of these recordings and the copious information contained in the book, the set offers a vivid look at an under-documented era in DC’s history—a time when a fast-growing African American population transformed the city, both demographically and culturally. “For me as a historian, it’s going to be absolutely invaluable,” says Georgetown history and African American studies professor Maurice Jackson, who coedited the 2018 book DC Jazz. “It’s an important time: In the 1940s and early ’50s, there’s a big movement to desegregate the city. In 1957, Washington becomes the first major city with a majority-Black population. But economically, Black people are not doing all that well. The incomes are so far behind the incomes of whites, even in the government. So music is a way to deal with those facts of life. This is basically working-class people’s music. It is the music of everyday Black people.”

“This era of music was pure–It was fun. They weren’t paid a lot. This was real passion.”

If you scan the liner notes of R&B in D.C., you’ll see some familiar names—renowned musicians such as Billy Eckstine, Don Covay, Billy Stewart, and Marvin Gaye, who shows up as a member of the Marquees and Harvey & the Moonglows. The latter group’s “Mama Loocie” is likely Gaye’s first-ever lead vocal released on record. But the set is primarily focused on lesser-known figures. You’ll get to know Delores “Baby Dee” Spriggs, a DC native who recorded racy singles like “It Feels So Doggone Good” and was described by the Washington Afro-American, in 1952, as “a package of dynamite.” You’ll meet street-corner vocal quartet the Blue Jays, who were students at Francis Junior High School when they recorded “Could I Adore You” in a small studio at 21st Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, Northwest. And you’ll spend time with Roosevelt High’s the Impalas, who started out as singers for Bo Diddley (back when he lived on Rhode Island Avenue, Northeast, and had a studio in the basement) and went on to a long career as the Jewels.

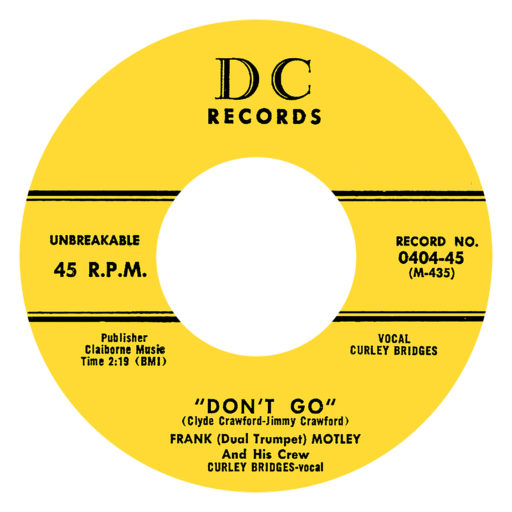

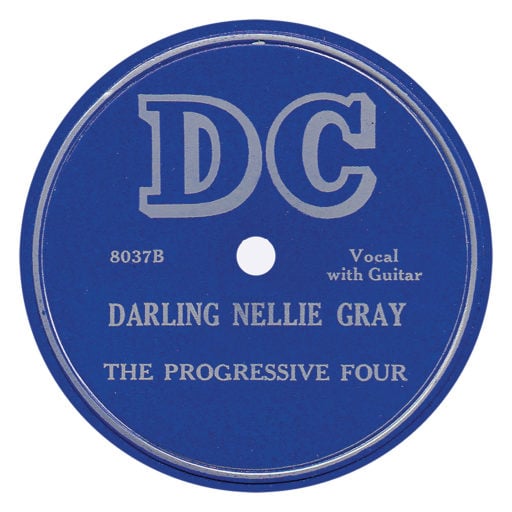

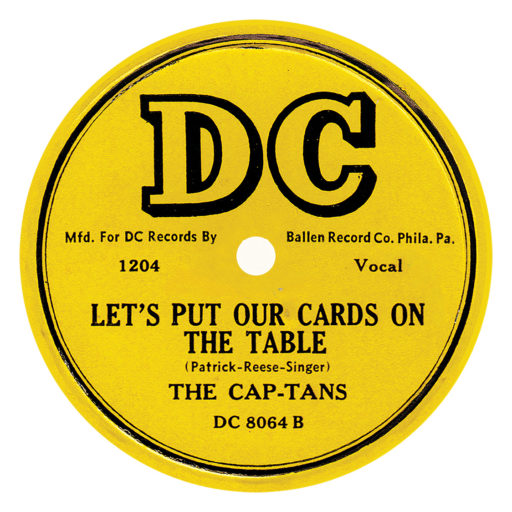

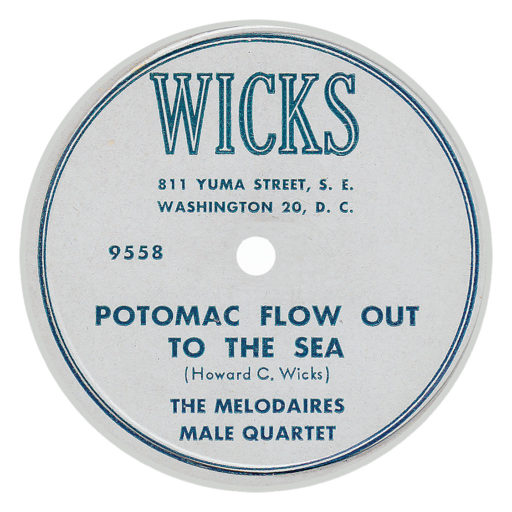

One character who pervades the set is Lillian Claiborne, the force behind a local company called DC Records as well as a crucial conduit between musicians of the period and other labels. Claiborne got her start releasing records by hillbilly and society artists (one called “The Wicked Little Cricket” was a minor hit), and she worked with Patsy Cline early in the country singer’s career. But it was the R&B scene in which she truly found her home. Claiborne, who died in 1975, helped birth a stream of significant records, including ones by the Progressive Four, the Cap-Tans, Frank Motley, and TNT Tribble himself. Bruder’s book devotes one of its longest chapters to her efforts.

Yet even members of Claiborne’s own family weren’t aware of her significance until recently. When Roy Graham connected with Bruder a couple of years back about his great aunt Lillian, he was under the impression that music had just been a sideline. Graham, who lives in San Antonio, remembers visiting Claiborne at an apartment on Connecticut Avenue and seeing records spread around the place. “My mother said, ‘Well, you know, I think it’s maybe a hobby,’ ” Graham recalls. “I never had any sense it was so extensive until Jay contacted me. It was very eye-opening and, frankly, great.”

Bruder’s path from that chat with Tribble to his work on this CD behemoth took him around the country and the globe, even as his ears stayed trained on sounds from DC’s past. Born into a military family, he split his high-school years between Northern Virginia and Beirut, where his father’s work had brought the family for a time. He got into early rock ’n’ roll and R&B in high school, soaking up vintage sounds on Alan Lee’s Disc Memory Show on WGTB and, a bit later, Dick Lillard’s program on WMOD. To a white teenager from the suburbs, the music just “seemed a lot more sincere than [what] I grew up with in the late ’60s and early ’70s,” says Bruder. “It can be pretty raw. But you know that these guys and gals are giving it everything they’ve got.”

After college, Bruder followed his father and grandfather into a career with the Marine Corps. Over the years, he was assigned to combat deployments in places like Lebanon, Kuwait, and Iraq, and he served as commanding officer of the Forward Operating Base at Fallujah for part of the Iraq War. He eventually reached the rank of colonel.

But Bruder’s obsession with DC music never faded. In fact, digging into vintage sounds had served as an escape from the stresses of his job. During down hours, he would hunt for rare records and key figures from Washington’s R&B scene.

When Bruder was assigned to Camp Lejeune in North Carolina in the late ’80s, he spent some time trying to get in touch with Frank Motley, a prominent bandleader on the old local circuit who had last been seen living in Canada. After months of working his sources (which involved reaching out to people with names like Bumblebee Slim), Bruder traced Motley to Durham—just a couple of hours away. The two ended up spending an afternoon together, and Bruder was able to conduct the in-depth interview he’d been after.

On his way home from their meeting, Bruder decided to stop at an antiques mall, as he often did, just to see if it had any old records. He started flipping through a pile of 45s, and literally the third one was “Heavy Weight Baby,” an ultra-rare single on the Specialty label that was recorded by none other than Frank Motley. “I’d been looking for that for 20-plus years!” Bruder says. “That’s serendipity. That’s divine providence.” Bruder brought his discovery to the counter and watched the clerk ring up his Holy Grail purchase. The price: 75 cents.

Bruder retired from the Marines in 2010. By that time, he had amassed an impressive library of obscure records and earned a reputation in record-collector circles as somebody who knew what he was talking about. His newfound free time meant he might finally be able to write a book about the history of DC R&B.

Then in 2014, while he was giving a presentation at a conference for recorded-sound archivists in North Carolina, Bruder met Richard Weize, founder of Bear Family Records, a German company known for lavish archival collections devoted to classic American country and rock ’n’ roll artists. Weize asked if he’d be interested in putting together a compilation for his label.

Bruder—a bespectacled bald guy whom you might mistake for a high-school math teacher—originally figured that the project would take about a year and a half to assemble and fill six CDs. But extra research and input from other collectors led to additions, and Bruder was able to trace some records he had thought were lost. By the time he was done, he had revamped the track list 23 times and added ten extra CDs.

In its finished form, the collection opens with a virtually unknown recording by a group called the Lyles Brothers, which Bruder discovered in an album of 78s at an antiques shop in Falls Church. If he hadn’t stumbled across this forgotten vanity pressing and decided to include it, that music might be lost for good. So while the box contains plenty of songs by, say, the Clovers, who rose to national prominence after signing with Ahmet Ertegun’s young Atlantic Records, well-known hits aren’t really the focus. “If you’re interested in the Clovers, you can find the Clovers” in other places, Bruder says. “If, on the other hand, you’re looking for Frank Motley, there’s a lot that’s just never been released.”

DC’s R&B scene didn’t produce a huge number of records that hit the national charts. But Bruder’s box set, with its extensive contextual info and illuminating photos and posters, captures just how vital it was as a local phenomenon. “This particular era of music, it was pure—it was fun,” says Motley’s grandson Morris Clarke, who was close to the musician when he was growing up in Durham. (Motley died in 1998.) “They weren’t paid a lot of money to do this. This was real passion.”

The collection also offers a cohesive narrative of a time and place and culture that—as participants pass away and demographic change erodes the city’s institutional memory—is fast fading. “I want everyone to learn about these people and the community that nurtured them in what was a pretty difficult period for the African American community in Washington, DC,” Bruder says. “These folks, they accomplished a lot. And no, they didn’t have a ton of national hits. But they made some great music.”

This article appears in the September 2021 issue of Washingtonian.