Dave Chappelle arrives in less than two hours, and now, go figure, it’s about to rain.

It’s a Sunday night at the end of a second Covid summer in Washington. Chappelle is downstairs in the Kennedy Center, back home to screen his new documentary about doing comedy in a pandemic. Once the credits roll, a crowd will parade up here to the rooftop for the after-party. The producer of the bash is a 39-year-old born-and-bred Washingtonian named Vinoda Basnayake, whom you can hereafter think of as our town’s hookup to the Washington Famous and the Actually Famous, too.

Basnayake’s bank-robber-themed Dupont nightclub, Heist, has been hosting sky-high parties atop the Kennedy Center all summer. But Chappelle’s private soiree is the most VIP yet—with a guest list of White House staffers, local-DC bigwigs, and the comedian’s closest friends. To top it off, Basnayake’s usual point man is out tonight; the logistical nightmare is all his.

An army of cocktail waitresses in skimpy red dresses drag lounge furniture beneath an overhang and cover the cabanas with tarps. About 250 guests are about to arrive all at once, and every single one needs to get a rapid Covid test to enter. Oh, and no phones allowed. A company called Yondr will put everyone’s devices in secure pouches they can’t access until they leave . . . only said company hasn’t actually set up in the right place yet. Basnayake grabs a Red Bull.

Not that he’s all that stressed. Basnayake—just “V” to his friends—used to be the tour manager for a mega R&B superstar, has done tequila shots with Justin Timberlake in Vegas, and once appeared in a music video with Nicki Minaj (blink and you’ll miss it, but still). For the past ten years, he has operated some of DC’s sceneiest clubs and bars, drawing an international crowd and big-name celebs. First was Eden, where Kevin Durant and Drake and the Backstreet Boys came to party. (Basnayake has since sold his stake.) Now there’s the cocktail den Morris American Bar, near the convention center; the Cuban-inspired hot spot Casta’s Rum Bar in Foggy Bottom; and Heist, which Michelle Obama rented for her 53rd birthday and where the Nats and Caps popped bottles after their championship wins. Washington isn’t exactly known for its nightlife, but when the scene does hit, say, Page Six, Basnayake’s spots tend to be the backdrop.

But get this—all while trying to build up the city as a Saturday-night playground for the young, trendy, and ready to party, Basnayake has also held down the most Washington job in Washington. He’s a lobbyist.

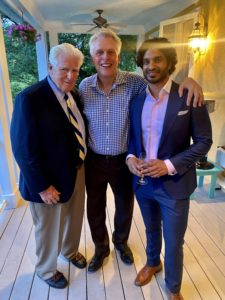

A protégé of the famed late King of K Street, Tommy Boggs, Basnayake reps foreign governments and corporations. He has the ear of government on both sides of the federal/local divide—a Hill top-lobbyist list-maker, a confidant of DC mayor Muriel Bowser, and no stranger to a White House holiday party. Between nightlife and swamp life, Basnayake has thrived in the murky thickets where it pays to be the guy who knows a guy.

He’s always introducing someone to their best friend/business partner/the former President of the United States.

And at Chappelle’s party, Basnayake knows them all: celeb chef Carla Hall, Nancy Pelosi senior adviser Michael Reed, and the Washington Football Team’s new president, Jason Wright. He upgrades Kamala Harris’s top spokeswoman, Symone Sanders, from a high-top in the back to his personal table in front of the stage and schmoozes with Bowser, whose group is in a private cabana ordering a magnum of rosé. (Says Basnayake: “The mayor likes rosé.”) When the Cellphone Police make DC police chief Robert Contee lock up his device, Basnayake is the one to help him get it back. Chappelle greets him with a hug.

As midnight approaches, the comedian takes the mike, red Solo cup and cigarette in hand. He pumps up the crowd to make some noise for the mayor’s birthday, then—“Quiet, everybody. I’ve got to get it on!”—croons Prince’s “1999.”

“Tonight, I guarantee, I will put money on it,” Basnayake said to me earlier, “somebody’s going to come up to me and say, ‘This doesn’t feel like DC. This feels like a rooftop in Miami. This feels like a rooftop in wherever.’ ”

But Washington’s power set is getting down to go-go tunes with the Lincoln Memorial behind them, while the guy running the show needs to be up in a few short hours for a partners meeting at his firm. So yeah, this isn’t Miami or LA or wherever. As Basnayake likes to say about his parties, “Nothing could be more DC.” And he’s kind of right.

Two things people will tell you about V: One, he’s not the type to make enemies, which is interesting because it’s usually the other way around for influential people. Two, he’s always introducing someone to their best friend/business partner/the former President of the United States. “Only Vinoda,” says chef Spike Mendelsohn of that time his buddy Basnayake arranged for him to shake Bill Clinton’s hand at a gala at the Ritz. “That’s like an expression amongst friends: Only Vinoda.”

Washington is full of preeners who want you to think they’re more important than they really are. Basnayake (pronounced Bahz-NEYE-ah-ka) knows everyone, but he’s no casual name-dropper. He may be a striver, skilled at the humblebrag and the other conversational arts that get you ahead—but he’s also legitimately charming. Maybe it’s the way he never seems like he’s trying too hard, down to his go-to basic white tee, Adidas kicks, and man bun. (Surprise: He’s also an investor in Karma by Erwin Gomez, the West End salon.) He doesn’t come off as an operator, which is probably what makes him so good at being an operator.

Consider the following story from Jim Moran, the former Virginia congressman, who’s now Basnayake’s colleague: An embassy had been trying for years to remove the parking meters in front of its building, out of security concerns. One day, Basnayake was there getting in his car and someone from the embassy casually mentioned it. Basnayake casually said he’d see what he could do. Within a week, all the meters were shut down. Turns out he’s pals with the guy who headed up the city’s transportation department at the time. An inspector looked into it, and that was that.

Moran first met Basnayake more than a decade ago when Basnayake was lobbying him on behalf of Sri Lanka. Moran didn’t think Sri Lanka was particularly relevant to him, but Basnayake’s persuasiveness convinced him to visit the country. “I remember him more than I do the issue itself,” says Moran. (The South Asian nation was trying to show US officials how people displaced during its civil war weren’t being mistreated.) In another life, Basnayake probably would have been an international explorer, Moran posits: “A modern-day Marco Polo—because he’s willing to explore different lands and meet people that other people might be intimidated by.”

Basnayake is a son of Sri Lankan immigrants. His mom worked at the World Bank, Dad is an immigration attorney. He grew up in Kalorama and McLean and went to Gonzaga for high school. The first real party he ever hosted was a mixer, for the International Student Union he cofounded. “We were minority kids in a predominantly white environment,” says Shiv Newaldass, one of Basnayake’s close high-school and college friends. “And in order to feel more integrated, we needed to do things to make sure we were known and visible.”

By the time they both enrolled at Georgetown, Basnayake was busy befriending bouncers and establishing himself as the go-to guy for going out. One night at Sole, the erstwhile late-night spot on the waterfront, the owner cornered him. “I was like, ‘Oh, shit, I’m going to get in trouble because I just got 30 underage kids in here.’ ” Instead, he says, the owner offered him his first promoter deal: If he quit sneaking people in on weekends, Sole would make Thursdays 18-and-Up Night; Basnayake could charge whatever he wanted at the door and pocket the cash. If the bar made more than $5,000, he’d get a 20-percent cut of the rest.

The side hustle morphed into a full-blown promotions company Basnayake ran with a friend. By the time he graduated, the finance/international-business double major was doing ten events a week. That year—2003—a DJ told him about an R&B singer who was blowing up in the UK. Basnayake had no clue how popular this guy actually was, but he booked the artist for his first US show. Tickets sold out immediately. So did a second night. “So we booked an entire US tour around it,” Basnayake says. “Every city sold out.”

Jay Sean—as the world would soon know him—had no idea he even had fans in America before Basnayake landed him the gig. Within a few years, he was a global superstar with multiple tracks topping the Billboard Hot 100. If you turned on the radio in 2009, chances are you got sucked into his “Baby are you down down down down down” earworm with Lil Wayne. “I’m South Asian. Vinoda’s South Asian. My first tour was heavily South Asian,” says Jay Sean, whose real name is Kamaljit Singh Jhooti. “Vinoda was a big part in being able to see how you can take a very niche fan base and how quickly that can spread.”

After graduation, Basnayake spent two years as Jay Sean’s tour manager, then continued to work with him off and on into the peak of the singer’s fame, touring with a young Justin Bieber and arranging shows with Taylor Swift and Bruno Mars. For someone else, it might have been a dream gig. And it was a blast. But Basnayake really wanted his own hospitality company and nightclubs. He enrolled in a joint program at Penn Law and Wharton Business School, aiming to build some credibility.

Then the most random thing happened. The summer before his second year, while most rising 2Ls were hitched to their desks at corporate law firms, Basnayake was still promoting. One of his venues was an outdoor nightclub at the Ronald Reagan Building, of all places. The building’s events director happened to be Barbara Boggs, who happened to be married to the famed Democratic lobbyist Tommy Boggs and who insisted Basnayake meet her husband. “She was like, ‘Just talk to him. I see all these VIPs and foreign dignitaries at your parties. I think your network of different people could be very valuable.’ ”

The following year, Basnayake landed a plum summer-associate position at Patton Boggs. He took it—why not, it was “something to do that was different.” But it was also the kind of job where you got to meet a presidential hopeful named Barack Obama and geek out with other politicos, so. He launched his first nightclub at the same time as his lobbying career.

Foreign lobbyists are longstanding fixtures of Washington’s influence industry who mostly managed to slip under the radar, until Donald Trump won the White House. Then came the scandalous headlines about Paul Manafort, Trump’s campaign chairman, and his right-hand, Rick Gates, who failed to disclose the $75 million they made running a covert lobbying operation on behalf of Ukrainian interests and broke a little-enforced federal law requiring foreign agents to share what they’re up to and who’s footing the bill. The jig was up—Beltway mercenaries secretly funded by less-than-savory governments were outed as a particularly icky breed of swamp creature.

Basnayake isn’t the lurk-in-the-shadows type. But even for an up-and-up registered foreign agent, the cloud of suspicion that developed after the Manafort fiasco is hard to escape. “There are certainly stigmas with nightlife and nightclubs, and there’s a ton of stigmas with lobbying and dark money and the whole industry of my day job,” Basnayake says. Not that everything he does is “God’s work,” he admits, but “I believe in what I’m doing. I wouldn’t put my name around an establishment that I thought was shit any faster than I’d take on a client whose cause I didn’t believe in.”

Basnayake got to Nelson Mullins in 2014 and three years later became the firm’s youngest partner, at age 35. He’s currently on the books as an agent for South Korea, a US ally with a trade-focused agenda in Washington, which is pretty much all he can say about that. He has helped Guinea get more Ebola aid from the US government and countered attacks on President Alpha Condé during his 2015 reelection (Condé, no longer a client, was recently overthrown following unrest over allegations of abuses of power). Then there was Karim Wade, a divisive, high-flying Senegalese minister imprisoned for allegedly embezzling hundreds of millions of dollars. A son of the country’s former president, Wade claimed to be the victim of a political witch hunt and hired Basnayake to push for his release by arguing to US officials, “Hey, this [supposedly] democratic government just arrested their opposition—we should care.” Wade was pardoned halfway through his prison sentence but still was ordered to pay a $230-million fine. “A successful campaign,” Basnayake says.

Basnayake’s biggest current client is Qatar, the über-wealthy Arab monarchy whose ruling Al Thani family holds ultimate power over the nation’s laws and courts. In Qatar, it’s a crime to be gay, women can’t marry without the blessing of their male guardians, and you can get seven years in jail for defaming Islam. Still, the Qataris have maintained largely simpatico relations with the US. In 2017, though, Saudi Arabia accused the Al Thanis of supporting terrorist groups and led a crippling trade boycott against Qatar in the Persian Gulf. Trump, fresh off a red-carpet Saudi trip, initially snubbed Qatar, too. Seeking more Washington influence, and a more flattering narrative, the Mideast nation boosted its spending bigtime with a slew of prominent lobbying and PR firms. According to the lobbying watchdog Open Secrets, Qatar paid Nelson Mullins $1.7 million in 2020 alone.

Lately, the work has been intense. When the Biden administration’s military pullout from Afghanistan went awry, Qatar —home to the largest American military base in the Middle East—won brownie points with the US by helping evacuate people from Kabul. Basnayake is one of the behind-the-scenesters keeping the relationship with Washington chummy. When Congressman Eric Swalwell, who has a large Afghan population in his California district, needed on-the-ground intel about specific individuals, Basnayake and his firm acted as go-betweens.

Repping the Qataris generally also involves more amorphous goodwill operations, aimed at casting a softer glow on the autocratic regime. And here’s where Basnayake’s night job can really come in handy. For Qatar’s annual autism-awareness gala (one of the country’s pet philanthropic causes, who knew?), Basnayake helps secure A-list entertainers. Qatar also wants to be viewed as a major patron of the arts, so the state is a longstanding sponsor of the Kennedy Center. “I’ve definitely played a role in shepherding that relationship,” Basnayake says, “and maybe even getting visibility for opportunities that they wouldn’t have otherwise necessarily known about.” Like a VIP cabana at a Dave Chappelle party full of administration types and other Beltway bigs.

It’s easy to see how there’s a special synergy, as they say, between lobbying and nightlife. Basnayake has met future clients at parties, and sometimes brings clients to his venues. “These embassies are staffed by young people,” says Bob Crowe, who hired Basnayake at Nelson Mullins. “With Vinoda, we have the ability to invite them to clubs and dinners, so it’s a great marketing tool.”

Of course, not every job is a party. Jim Moran tells me about the time a Nelson Mullins client wanted “the most impressive building in DC, whether it was for sale or not.” The “distinguished, iconic” organization that owned the building didn’t officially have it on the market, but Basnayake had heard rumors they might be willing to sell and brought it to the ambassador’s attention. While Moran declined to name the client, Basnayake confirms what some basic Googling will tell you: He’s talking about Qatar’s controversial bid to buy the Carnegie Institution for Science’s treasured Beaux-Arts headquarters near Dupont Circle earlier this year.

Moran says Basnayake “got a couple of us who know board members [at the organization] to call them at night” to encourage the sale, in conjunction with more extensive negotiations led by the Qatari ambassador.

After the sale was announced internally, though, more than 100 Carnegie employees and associates wrote a letter to the organization’s leadership decrying a transaction with an “oppressive, brutal, and misogynistic regime,” the Washington Business Journal reported.

“There are certainly stigmas with nightlife and nightclubs, and with the whole industry of my day job.” Not that everything he does is “God’s work,” he admits, but “I believe in what I’m doing.”

Ultimately, Carnegie stood by the deal Basnayake helped orchestrate. The group’s president, Eric Isaacs, told Science magazine that the board of trustees “thought long and hard” about Qatar’s human-rights record, but “this was a decision to convert as much of our capital into science as possible.” The building’s final sale price was $65 million, nearly three times its assessed value.

When Basnayake bought Heist in 2017, he inherited the bank-robber theme and all its gimmickry—the (yes, real) bullet holes along the brass bar, the golden urinals, the vaults for Champagne. But he did change some of the more important features of the place. A lot of clubs tended to segregate their audience with hip-hop one night, Latin night another; Basnayake ditched promoters and made the music open-format every night. He also nixed cover charges and dress codes. “Nightclubs pride themselves on exclusivity,” he says, “which is them basically being dicks at the door.”

Basnayake had been the kid turned away for his sneakers, no matter whether they cost twice as much as another guy’s loafers, and wanted none of that. Plus, the appeal of clubs for him was meeting random people. Heist was about the “perfect storm” of college kids mixing with C-suiters and celebs.

“No one sees me as a nice guy,” says Marc Barnes, the legendary DC nightlife operator behind Dream, Love, and the Park at 14th. “Marc Barnes is the asshole because I state my opinion. But Vinoda has got to walk the fence. Vinoda’s the ultimate promoter because that’s what lobbyists are. They’re people that everybody likes and that can get along with everyone. They never really say or do anything bad. They just figure out a way to get things done.”

One of the bigger things colleagues credit Basnayake for getting done is working his connections at the Wilson Building to get more respect for the city’s nightlife scene. Basnayake became close friends with former mayor Adrian Fenty while volunteering for his campaign as a law student, and in turn befriended Fenty’s ally Bowser (who hooked him up with a “202” vanity plate for his matte-black G-Wagen). When officials began chattering a few years ago about creating a DC Office of Nightlife and Culture, Basnayake traveled around the country with then-councilmember Brandon Todd to see how other cities were doing it. DC’s nightlife commission was ultimately created in 2018, and the mayor tapped Basnayake as the inaugural chair. “Most nightlife and music venues in general . . . felt like they were constantly picked on and looked down upon and restaurants got all the attention and love,” explains Matt Cronin, general manager at Echostage. “And I think Vinoda did a lot to make downtown realize [nightlife] was an important part of the identity of DC.”

Last year, the commission had just released the first-ever report on the $7-billion economic impact of the industry when the pandemic completely shut it down. Basnayake became a key liaison between venue operators and the mayor’s office, organizing Zooms and helping the city think through its relief programs as he tried to figure out how to keep his own businesses afloat. He enrolled in a six-week digital-marketing class to help goose traffic at his spots, then up and launched an entire digital-media marketing agency. (The firm now has a staff of eight and runs campaigns for national clients, including his buddy Jay Sean’s new sparkling-sake brand.)

Casta’s Rum Bar had its covered outdoor patio; Morris pivoted to delivery cocktails. But subterranean Heist was deep in the red with no hope of reopening anytime soon. Unless maybe Basnayake could bring bottle service outdoors somewhere? “Then I was like, ‘I’m going to contact every national monument and suggest the idea of doing a socially distanced outdoor nightlife experience.’ ” The Sculpture Garden at the National Gallery of Art ghosted him. The Kennedy Center bit.

Attendance was capped at 360 people, and top-tier cabanas listed for $1,000. Tickets for the first night sold out in 15 minutes. In Basnayake’s mind, the concept was no different than what every other bar and restaurant in DC was already doing: They’d have socially distanced tables, serve food, and use a music playlist “curated” by DJs rather than hosting actual DJs, who were banned under city regs.

But the District simultaneously announced a live-entertainment pilot program, which allowed some venues to host events with no more than 50 people. Heist on the rooftop wouldn’t have live acts, but the timing and billing of the clubby pop-up stirred confusion and resentment. Some nightlife operators were rankled by what they perceived as special treatment for someone so wired into city government. “I think people were really startled and irritated by what seemed to be a special accommodation for him,” says one person involved in the scene who wished to remain anonymous because he didn’t want to sour his relationship with Basnayake. “It smacked of an insider deal.”

Basnayake says this is one case in which he pulled no special strings and the venue was publicly available for anyone to rent. Nonetheless, the Kennedy Center brass backed out for the time being. As Basnayake recalls them telling him, “If it’s going to be controversial, it goes against what we wanted, which was to uplift people.” He agreed. “I’m a very positive person, and this is something that I’m kind of bitter about.”

Basnayake lives in a five-story, ultramodern townhouse-with-elevator in Arlington with his two cats. (His rescue with gunshot wounds, Tupac, was recently voted the Animal Welfare League of Alexandria’s “Animal of the Year,” thanks to Basnayake’s promoter skills.) He also owns a place in Dupont Circle.

He has started seriously buying art, and his collection is pretty sick. Last year, he turned on Antiques Roadshow and stumbled onto an episode showcasing drawings that Kanye West did as a teenager. Basnayake is a big fan, having produced one of the rapper’s concerts the year of his first hit album. The art was presented by the husband of the superstar’s first cousin; Basnayake managed to track the relative down and offered to buy the drawings, valued at up to $23,000, for an undisclosed sum. They weren’t interested, he persisted, they relented. Only Vinoda.

Sure, Basnayake could more than get by on just one of his careers, but that would be like neglecting half his brain. Lobbying scratches that strategic itch, nightlife hits his creative needs. So, naturally, as the pandemic recedes, he’s doubling the size of his hospitality company.

For starters, he’s reopening Heist this winter with a totally new look (see ya, bullet-riddled bar) and running a “Haunted Heist” Halloween pop-up at Markoff’s Haunted Forest near Poolesville (think zombies and VIP tables strewn amid the cornfields). A rooftop lounge, Ciel Social Club, just opened at the new AC Hotel by Marriott in Mount Vernon Triangle. At FedExField in Landover, Basnayake is in talks about a lounge where the football crowd would get a nightclub experience during a game—a trend that has already caught on in Miami and Las Vegas stadiums.

Then there’s Leila, a Persian/Arabic/Indian restaurant and hookah lounge neighboring an Auntie Anne’s in Tysons Corner Center. During Covid, he has noticed that suburbanites are going out closer to home. And Tysons is hot. So he wants Leila to benefit from being inside one of the busiest malls in America without it feeling like one of the busiest malls in America. Picture Mediterranean-style day beds on the patio and moody window treatments to block the views of the Sunglass Hut.

In one of the brief down moments before the Chappelle party, I ask him how he balances two careers or, you know, sleeps. “As exhausted as I am right now and as tired as I probably look right now,” he says, “the minute this thing turns on, I turn on.” Okay, but does he ever take a day off? “I mean . . . it’s just that like . . . .”

Finally, he pulls out his phone and shows me a photo of a plaque on his desk:

A master in the art of living makes little distinction between his work and his play, his labor and his leisure, his mind and his body, his education and his recreation, his love and his religion. He barely knows which is which.

“That’s my thing,” he says. Then Chappelle’s publicist arrives, and Basnayake is on.

This story has been updated to clarify the details behind the Carnegie building sale.

This article appears in the November 2021 issue of Washingtonian.