Bob Dole—a Washington fixture who served for 27 years as a Republican Senator from Kansas, and was also a former candidate for both the presidency and vice-presidency—died in his sleep on Sunday at the age of 98. Last February, he had revealed he was being treated for lung cancer.

In February 1985, Washingtonian ran the following profile of Dole, who had been elected Senate Majority Leader the year before.

Here is the text of that 1985 article:

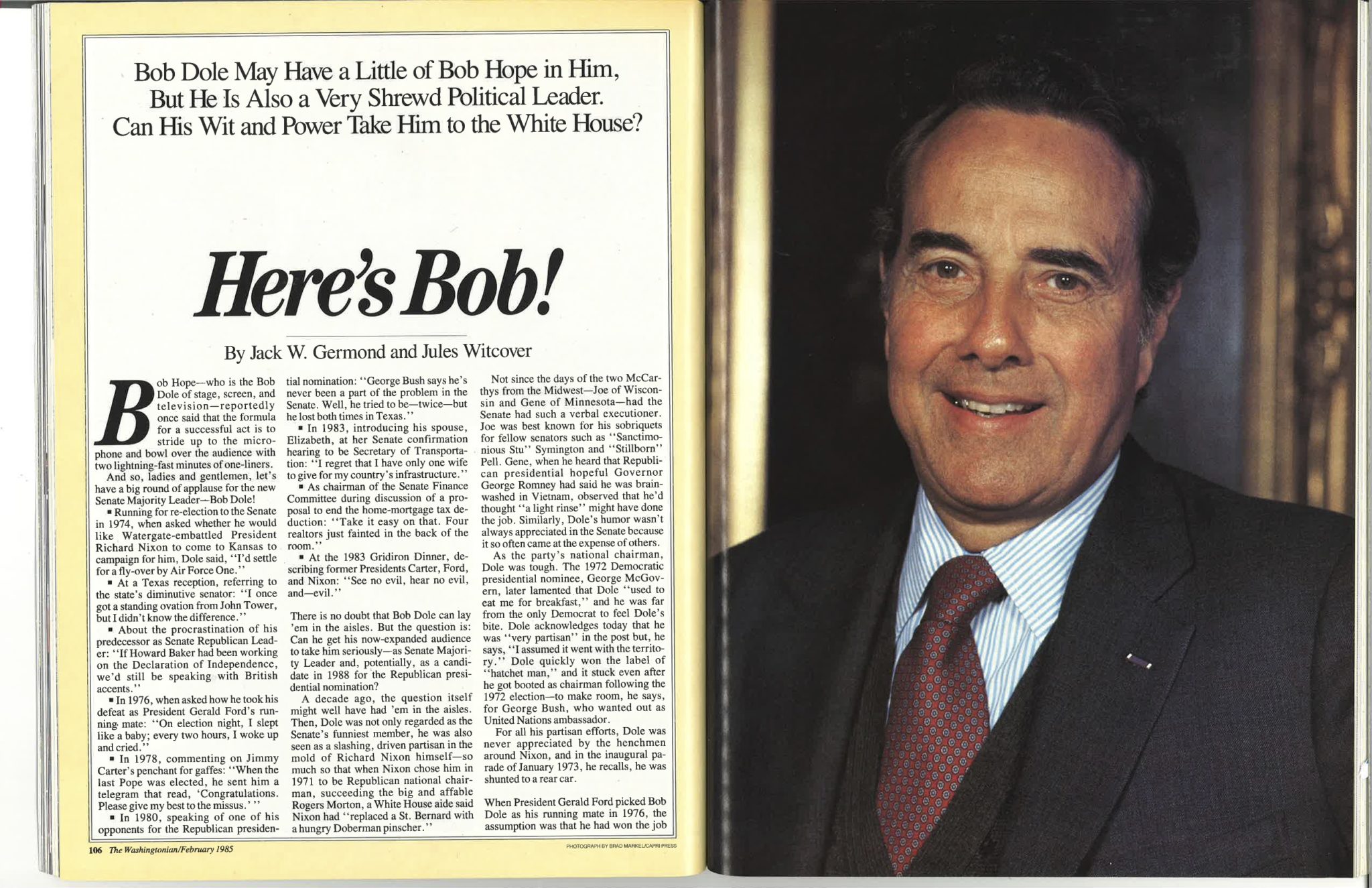

Bob Hope — who is the Bob Dole of stage, screen, and television — reportedly once said that the formula for a successful act is to stride up to the microphone and bowl over the audience with two lightning-fast minutes of one-liners.

And so, ladies and gentlemen, let’s have a big round of applause for the new Senate Majority Leader — Bob Dole!

- Running for re-election to the Senate in 1974, when asked whether he would like Watergate-embattled President Richard Nixon to come to Kansas to campaign for him, Dole said, “I’d settle for a fly-over by Air Force One.”

- At a Texas reception, referring to the state’s diminutive senator: “I once got a standing ovation from John Tower, but I didn’t know the difference.”

- About the procrastination of his predecessor as Senate Republican Leader: “If Howard Baker had been working on the Declaration of Independence, we’d still be speaking with British accents.”

- In 1976, when asked how he took his defeat as President Gerald Ford’s running-mate: “On election night, I slept like a baby; every two hours, I woke up and cried.”

- In 1978, commenting on Jimmy Carter’s penchant for gaffes: “When the last Pope was elected, he sent him a telegram that read, ‘Congratulations. Please give my best to the missus.’”

- In 1980, speaking of one of his opponents for the Republican presidential nomination: “George Bush says he’s never been a part of the problem in the Senate. Well, he tried to be — twice — but he lost both times in Texas.”

- In 1983, introducing his spouse, Elizabeth, at her Senate confirmation hearing to be Secretary of Transportation: “I regret that I have only one wife to give for my country’s infrastructure.”

- As chairman of the Senate Finance Committee during discussion of a proposal to end the home-mortgage tax deduction: “Take it easy on that. Four realtors just fainted in the back of the room.”

- At the 1983 Gridiron Dinner, describing former Presidents Carter, Ford, and Nixon: “See no evil, hear no evil, and — evil.

There is no doubt that Bob Dole can lay ‘em in the aisles. But the question is: Can he get his now expanded audience to take him seriously — as Senate Majority Leader and, potentially, as a candidate in 1988 for the Republican presidential nomination?

A decade ago, the question itself might well have had ‘em in the aisles. Then, Dole was not only regarded as the Senate’s funniest member, he was also seen as a slashing, driven partisan in the mold of Richard Nixon himself — so much so that when Nixon chose him in 1971 to be Republican national chairman, succeeding the big and affable Rogers Morton, a White House aide said Nixon had “replaced a St. Bernard with a hungry Doberman pinscher.”

Not since the days of the two McCarthys from the Midwest — Joe of Wisconsin and Gene of Minnesota — had the Senate had such a verbal executioner. Joe was best known for his sobriquets for fellow senators such as “Sanctimonious Stu” Stymington and “Stillborn” Pell. Gene, when he heard that Republican presidential hopeful Governor George Romeny had said he was brainwashed in Vietnam, observed that he’d thought “a light rinse” might have done the job. Similarly, Dole’s humor wasn’t always appreciated in the Senate because it so often came at the expense of others.

As the party’s national chairman, Dole was tough. The 1972 Democratic presidential nominee, George McGovern, later lamented that Dole “used to eat me for breakfast,” and he was far from the only Democrat to feel Dole’s bite. Dole acknowledges today that he was “very partisan” in the post but, he says “I assumed it went with the territory.” Dole quickly won the label of “hatchet man,” and it stuck even after he got booted as chairman following the 1972 election — to make room, he says, for George Bush, who wanted out as United Nations ambassador.

For all his partisan efforts, Dole was never appreciated by the henchmen around Nixon, and in the inaugural parade of January 1973, he recalls, he was shunted to a rear car.

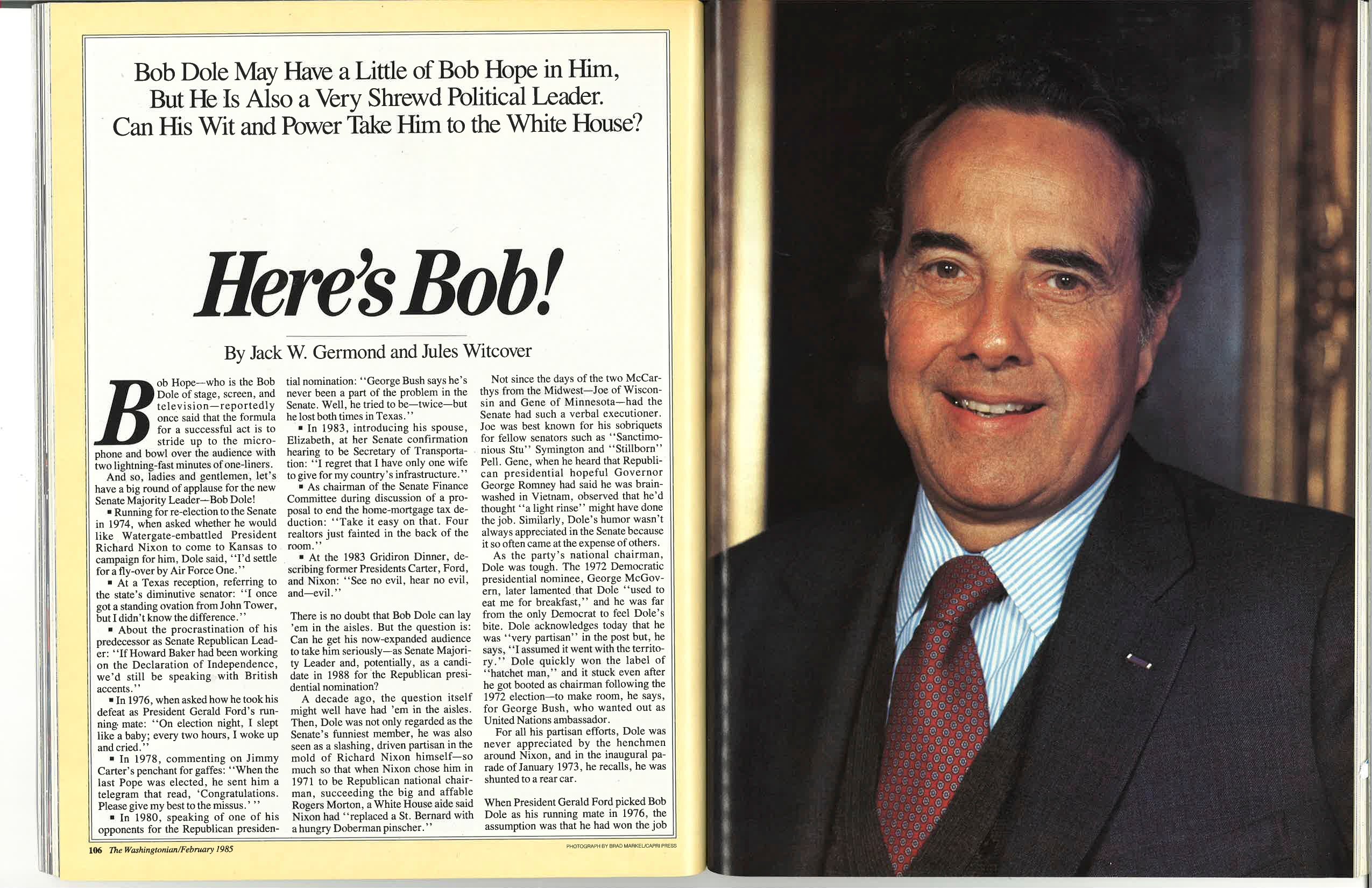

When President Gerald Ford picked Bob Dole as his running mate in 1976, the assumption was that he had won the job because he was such an experienced and effective ax-wielder. That view was reinforced in his debate with the Democratic vice-presidential nominee, Walter Mondale. Dole was his most acerbic–first trying to wisecrack his way through, then ranting at “Democrat wars”–one of which, he said, was World War II.

Many Republicans blamed the narrow loss of the Ford-Dole ticket to Carter-Mondale on Dole’s performance that night, though Ford himself credited Dole with holding the farm belt as well as the more conservative wing of the party. While Ford was campaigning from the Rose Garden, Dole observed later, he was assigned to “the briar patch” in the traditional running mate’s role of attacking the opposition and trying to be a lightning rod for the presidential candidate.

Later, he told dinner audiences: “I’ll never forget the Dole-Mondale debate–and don’t think I haven’t tried. I won’t say how we did, but halfway through the debate, three empty chairs got up and walked out. . . . President Ford was supposed to take the high road, and I was supposed to go for the jugular. And I did–my own.”

In the wake of the Ford-Dole defeat, he recalls, Nixon called and warned him, “Now it’s scapegoating time.” But Dole weathered the criticism, and today he says of that 1976 defeat, “I’m sort of the survivor. Carter’s gone, Ford’s gone, Mondale’s gone. I’m still here.”

After the 1976 campaign, Bob and Elizabeth Dole sat down together and watched television tapes of the debate with Mondale as well as other campaign performances. Whether or not that exercise led him to blunt the point of his oratorical spear, he did seem to wield it with more discipline thereafter. His humor had always had a self-deprecating style, and this aspect increasingly dominated–to the relief of his colleagues.

As Dole approached 1980 and his first try for the GOP presidential nomination, he already had put much of the criticism for harshness behind him. “As long as you turn it on yourself, you’re all right,” he says now. “But you get on a roll sometimes,” he adds with a wry grin, “and your judgement leaves you. I try not to be a free spirit so much anymore.”

In competition with Ronald Reagan on the 1980 campaign trail, neither Dole nor any of the other Republican candidates was a fair match. He still led the league in one-liners, but he never achieved much political identification outside Washington.

As a long-time member of the minority party in the Senate, he never had much opportunity to demonstrate legislative effectiveness and political leadership. Dole ran poorly in the Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary and then got out of the race.

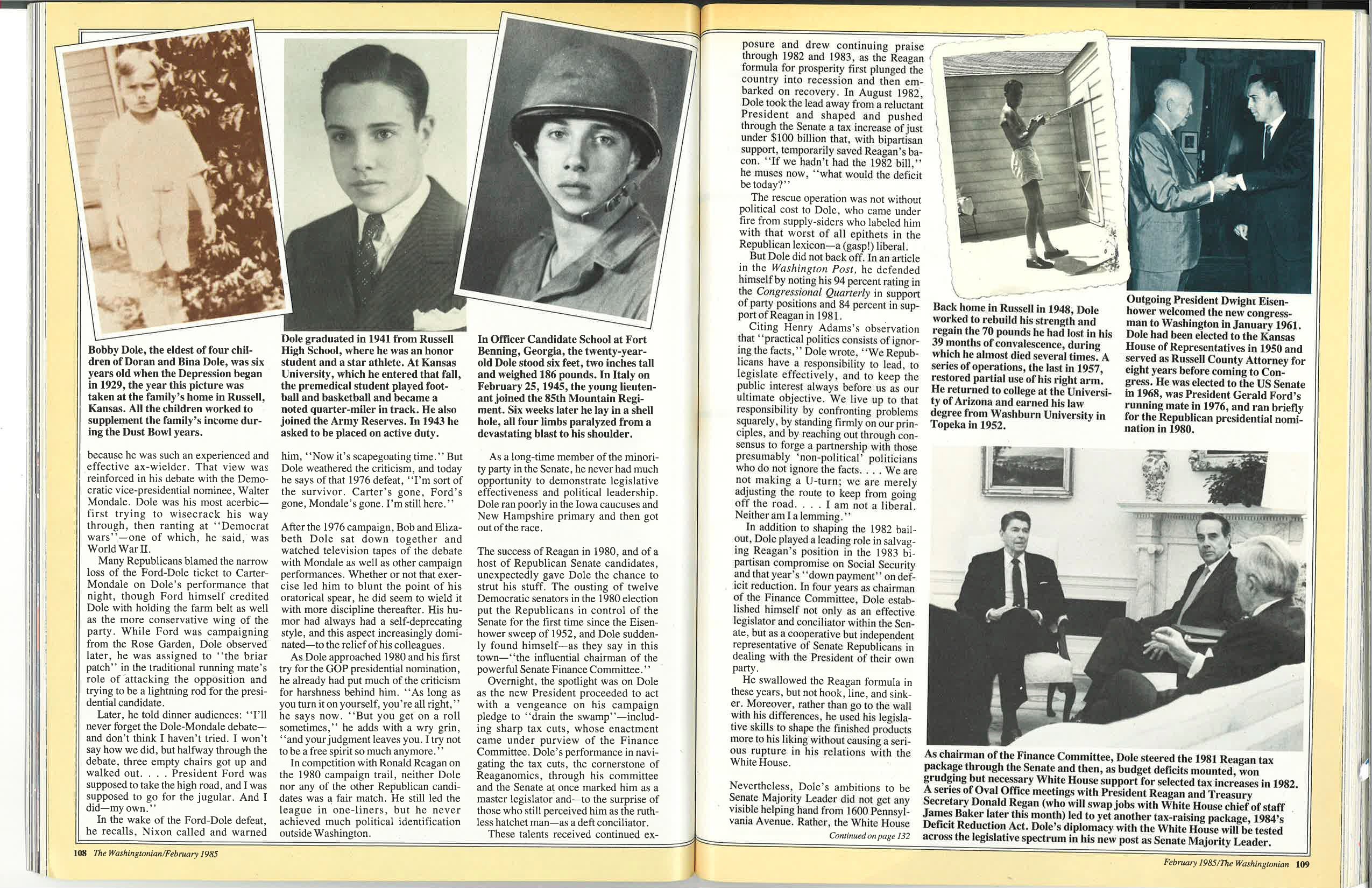

The success of Reagan in 1980, and of a host of Republican Senate candidates, unexpectedly gave Dole the chance to strut his stuff. The ousting of twelve Democratic senators in the 1980 election put the Republicans in control of the Senate for the first time since the Eisenhower sweep of 1952, and Dole suddenly found himself–as they say in this town–”the influential chairman of the powerful Senate Finance Committee.”

Overnight, the spotlight was on Dole as the new President proceeded to act with a vengeance on his campaign pledge to “drain the swamp”–including sharp tax cuts, whose enactment came under purview of the Finance Committee. Dole’s performance in navigating the tax cuts, the cornerstone of Reaganomics, through his committee and the Senate at once marked him as a master legislator and–to the surprise of those who still perceived him as the ruthless hatchet man–as a deft conciliator.

These talents received continued exposure and drew continuing praise through 1982 and 1983, as the Reagan formula for prosperity first plunged the country into recession and then embarked on recovery. In August 1982, Dole took the lead away from a reluctant President and shaped and pushed through the Senate a tax increase of just under $100 billion that, with bipartisan support, temporarily saved Reagan’s bacon. “If we hadn’t had the 1982 bill,” he muses now, “what would the deficit be today?”

The rescue operation was not without political cost to Dole, who came under fire from supply-siders who labeled him with the worst of all epithets in the Republican lexicon–a (gasp!) liberal.

But Dole did not back off. In an article in the Washington Post, he defended by noting his 94 percent rating in the Congressional Quarterly in support of party positions and 84 percent in support of Reagan in 1981.

Citing Henry Adams’s observation that “practical politics consists of ignoring the facts,” Dole wrote, “We Republicans have a responsibility to lead, to legislate effectively, and to keep the public interest always before us as our ultimate objective. We live up to that responsibility by confronting problems squarely, by standing firmly on our principles, and by reaching out through consensus to forge a partnership with those presumably ‘non-political’ politicians who do not ignore the facts…. We are not making a U-turn; we are merely adjusting the route to keep from going off the road…. I am not a liberal. Neither am I a lemming.”

In addition to shaping the 1982 bailout, Dole played a leading role in salvaging Reagan’s position in the 1983 bipartisan compromise on Social Security and that year’s “down payment” on deficit reduction. In four years as chairman of the Finance Committee, Dole established himself not only as an effective legislator and conciliator within the Senate, but as a cooperative but independent representative of Senate Republicans in dealing with the President of their own party.

He swallowed the Reagan formula in these years, but not hook, like, and sinker. Moreover, rather than go to the wall with his differences, he used his legislative skills to shape the finished products more to his liking without causing a serious rupture in his relations with the White House.

Nevertheless, Dole’s ambitions to be Senate Majority Leader did not get any visible helping hand from 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Rather, the White House hunkered down during the intense electioneering for the late-November balloting that led to Dole’s narrow election over the Senate assistant Majority Leader, Ted Stevens of Alaska. In the end, in fact, a belief among his colleagues that Dole would protect the Senate’s prerogatives while carrying the President’s mail on Capitol hill was a major factor in his election.

Now, unsurprisingly, there is nothing but praise coming from the White House about the choice. Outgoing White House chief of staff James Baker predicts Dole will be “an extremely successful Majority Leader, as perhaps the very best legislative tactician and strategist in the Senate. We found that to be the case in the first four years, during his tenure as chairman of the Finance Committee. And contrary to what people may say about his independence, while he felt free to question the President on some things, when the President decided, bob was with him more times than not.”

Senators on both sides of the aisle, and especially those who have served on the Finance Committee with him, also predict that Dole will be an effective Senate leader. Republican John Chafee of Rhode Island says Dole “has an excellent capacity for bringing people together and touching all bases so people won’t be surprised. He makes sure you get your day in court.” Chafee says Dole’s sense of humor will stand him in good stead because it has softened and because it is natural and not programmed. “His wit is not into the class-clown area by any means,” he says. “He’s not always groping for the gag, as some people do.”

Democrat George Mitchell of Maine says that Dole, while not regarded with the affection in which retired Majority leader Howard Baker was held, is seen as “very able, intelligent, and articulate—aggressive and ambitious in the good sense of those words.” And Democrat Bill Bradley of New Jersey calls him “a strong leader, fair and knowledgeable, who understands compromise and how to deal across the aisle.”

On the far right, Dole remains anathema to many. Representative Newt Gingrich of Georgia, in a stinging letter late last year to budget director David Stockman, referred derisively to Dole as “the tax collector for the welfare state.” Dole has been a particular champion of the food-stamp program and of programs for the handicapped, but he cannot fairly be accused of being an apostle of the federal handout. He is the founder of the nonprofit Dole Foundation in Kansas that helps train and employ the disabled in the private sector.

Gingrich says he was “angry” when he wrote the letter and that it wasn’t intended for publication. And Dole’s observations right after his election as Majority Leader that he would take a look at a budget freeze, Gingrich says, suggested that he was “backing off tax increases” —death to supply-siders such as Gingrich, who says economic growth in “the Opportunity Society” will solve the deficit dilemma.

Others on the right are not so hopeful about Dole. Conservative master fundraiser Richard Viguerie calls Dole “Mr. Tax-Increaser ” and says he is no conservative. “Would you say,” he asks, “that someone George McGovern has said ‘has grown’ can be considered a conservative?” Dole for his part, observes, “I can’t be all bad. Viguerie’s against me.”

The opposition to Dole on the right, where he once seemed to sit very comfortably, is only one roadblock in a run for the 1988 Republican presidential nomination from the post of Senate Republican leader. Dole, in keeping with protocol, is not saying he will be a presidential candidate again. For one thing, he faces re-election to the Senate in 1986. His wife, Elizabeth, says they have not even talked about it, choosing to focus on the challenge of the Senate leadership for now.

But assuming he wants to shoot for the White House in 1988, some Senate colleagues and others doubt the wisdom of seeking the presidency while carrying the burdens of party leadership in the Senate. One reason for Howard Baker;s decision to quit not only the Majority Leader’s post but ht eSenate itself was that he was convinced that his unsuccessful 1980 effort to run for President—he was only Minority Leader then—was handicapped by his heavy duties on Capitol Hill. Baker insists that this reason was not his prime consideration in leaving the Senate, though he admits few seem to believe him. “Principal for me is that eighteen years is long enough,” he says, “and if I’m ever going to do anything else, whether it’s political or non-political, now is the time to do it.”

Dole himself, when he was faring poorly in the 1980 presidential race, expressed reservations about seeking the presidency from the Senate. “I guess it’s hard to give two jobs 100 percent,” he said then. “Maybe I’ve been too cautious. You can’t generate any money money if you’re not out there. Maybe I’m my own worst enemy. It’s so strange, but my biggest liability—my job.” If that observation was valid five years ago, it would seem even more so now, with Dole’s greatly increased Senate responsibilities.

There is, at the same time, an up side to the situation. For one thing, Dole, as the former Finance Committee chairman and present Majority Leader, ought to have a much easier job raising money for a presidential campaign than he had in 1979 and 1980. For another, as Majority Leader for at least the next two years, he will be much more influential—and hence likely to draw much more media attention—than was Baker as Minority Leader in 1979 and 1980. Dole will be seen coming out of the White House so often in the next two years that he’ll look as if he has set up premature residency.

The realities of politics may also work in Dole’s favor. As matters stand now, the chances seem good that he will have to surrender his Majority Leader post and slip down to Minority Leader in 1987. Of the 34 Senate seats up in 1986, 22 are held by Republicans and only twelve by Democrats, so the odds favor the Democrats’ regaining control. By that time, Dole should have obtained his biggest publicity boost from being Majority Leader and the somewhat lesser duties of Minority Leader might make it easier for him to focus on another presidential bid.

Dole says his first priority politically will be to retain GOP control of the Senate. His own political-action committee, Campaign America, already has $500,000 in the till that will go primarily for the re-election of Republican senators—and, not incidentally, the storing away of political IOUs.

Dole’s observation upon being elected Majority Leader that holding on to the Senate was number-one with him and that Senate Republicans would support Reagan “when we can ” raised some eyebrows at the time, hinting as it did at the famous Dole independent streak. On that point, Howard Baker says, “He has one fundamental question to decide, the same question I had. I had to decide whether to be a Bob Taft or a Bill Knowland. Bob Taft [as Majority Leader] decided to support President Eisenhower, and he did it with great grace and skill. Knowland tried to be President himself. He lost the Senate, got himself defeated, and damaged Eisenhower. I read with great interest the columns and newspaper accounts about how independent the Senate may be [under Dole], and that’s all well and good. The Senate is an independent body. But it’s also going to be part of the team, and the leader has to be the point man, and I rather expect Dole will come down on that side.”

Baker says he and Dole have discussed the matter of running for President from the Majority Leader’s post, “and we’ve acknowledged one of us is making a mistake.” Baker points out that the job has “built-in pitfalls” that go beyond the possibility of differing with the President on specific votes and being tied down to the Senate. The Majority Leader, he says, “has the necessity of dealing with the other fellows’ issues every day and leaving precious little time for talking about your own positions and issues.”

Concerning the possibility of a conflict between Dole’s role as Majority Leader advancing a Republican President’s legislative goals and the need of a presidential hopeful to demonstrate independence, Jim Baker says the White House isn’t worried. “It’s not easy to run for President from the majority leadership,” he says. “I think that’s one reason Howard Baker got out. I don’t see Bob using that office to maintain an independent posture from the President. The best way to be a presidential candidate is to be a good Majority Leader, and to be a good Majority Leader he will want to work with the President.”

Dole says that while “1988 is probably remote for me,” he doesn’t agree with Howard Baker that being Majority Leader would be detrimental in seeking the White House. He says he knows he will have to walk a fine line between working with Reagan and defending his own and the Senate’s independence, but he notes his strong record of support for the President over the last four years and says he sees no reason it can’t be continued while retaining independence. “I can’t serve the Senate and be a lap dog,” he says bluntly. And Bill Bradley, who himself is being mentioned as a 1988 presidential prospect on the Democratic side, says, “There ought to be a moratorium on talking about everybody’s presidential ambitions for at least eighteen months.”

Finally, there is what one of Bob Dole’s colleagues calls his “extraordinary energy and stamina.” Lean and fit at 61, he has been a whirlwind of activity not only as chairman of the Finance Committee but in taking leadership roles on legislation in his other two committee assignments before becoming Majority Leader—on Agriculture and Judiciary—and on the Senate floor.

Elizabeth Dole says her husband’s being Majority Leader won’t change their lives all that much because he’s always on the go anyway. Another presidential campaign would only be in keeping with the all-out pace that has been his lifestyle for years.

Four years is a long time, and a lot can happen to clarify whether it will make sense for Bob Dole to try one more time for the White House in 1988. He has long since demonstrated that he has the sense of humor to be a very popular President, and in moving up to Senate Majority Leader he has shown he has the legislative and conciliatory talents to lift him to the vanguard of Capitol Hill operatives. But as a national figure able to draw the kind of support required for election to national office, he remains a question mark, with his 1976 and 1980 setbacks marked up against him.

Like Howard Baker before him, Bob Dole has succeeded far more inside the Beltway than outside it. One of his critics, Viguerie, observes that Dole’s quick wit and independence have made him a special favorite of the news media in Washington without giving him a comparable national constituency. “Try taking it into Iowa, New Hampshire, and Florida [early caucus and primary states],” he says. “News-media popularity is capital you can’t spend there, and it has a short shelf life.” In fact, Viguerie insists, such popularity is a negative nowadays. “It’s inconceivable now that anyone who has the support of the national media is going to get the Republican nomination,” he argues.

For now, Bob Dole is riding high, and he doesn’t have to resort to Bob Hope one-liners to get attention. He used to get a laugh by asking Republican audiences, “Can you hear me on the left? I know you can hear me on the right.” Now when Bob Dole, Majority Leader of the United States speaks, even E.F. Hutton listens. Especially E.F. Hutton.