Even if you did know the address of Ed Maibach’s office, you could walk right past it without a second thought. It’s in an anonymous-looking building in a perfectly ordinary stretch of the Virginia suburbs. The indistinct setting suits Maibach, who—due to the nature of his work—doesn’t list its physical location on his website. “Simply because,” he says, “there are a lot of crazy people out there who have a lot of anger and feel entitled to express their anger in really inappropriate ways, and sometimes really dangerous ways.”

Maibach’s professional endeavors are similarly discreet. Though he labors each day to alert Americans to the dangers of climate change, you won’t find him waving a NO FOSSIL FUELS banner from atop a tall building or protesting outside a congressional lawmaker’s home. Instead, this George Mason University professor deploys a behind-the-scenes strategy that would impress the savviest operators on K Street. Except rather than shilling for tech giants or Big Pharma, he works on behalf of the Earth.

About 13 years ago, Maibach identified a TV meteorologist in Columbia, South Carolina, who was willing to use his airtime not just to provide tomorrow’s forecast but to show viewers how climate change was impacting their local community. Over the next decade, Maibach would expand this experiment into what you might call a weather underground—a coast-to-coast network of TV weathercasters who believe that educating their audiences about global warming is as crucial as telling them when to bring an umbrella. The initiative, known as Climate Matters, has forced Maibach to confront a series of entrenched problems inside the broadcast-meteorology community, including alarming levels of climate denial and skepticism, fears about alienating audiences, and the occasional harassment of participating weathercasters. Yet by the end of 2021, the Climate Matters network of meteorologists had penetrated into nearly every media market in the country, and Maibach had pioneered a promising new approach to a complex crisis.

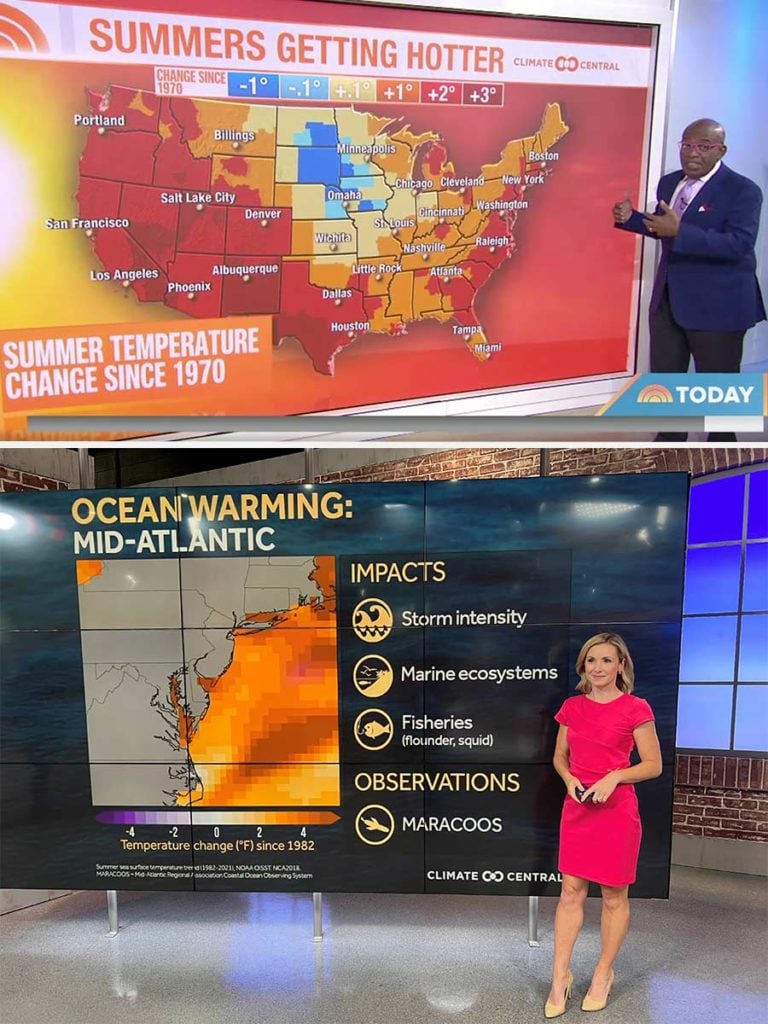

Truth is, if you’ve recently watched the weather report on the local news in the Washington area, there’s a decent chance you’ve seen Maibach’s handiwork—the Climate Matters network now includes weathercasters at NBC4, WUSA9, WJLA7, and Fox 5. But like local-news consumers across the country, you wouldn’t have known that behind that telegenic meteorologist are a social scientist in his sixties and a team of academic researchers, data crunchers, and ex-weathercasters. “To a lot of our viewers, it’s lost on them how much work Climate [Matters] really is doing,” says Kaitlyn McGrath, a meteorologist at WUSA9. “But it is so far from lost on us.”

It all began in 2008, when Maibach teamed up with a fellow academic researcher, Anthony Leiserowitz of Yale, to try to get a better sense of how the public felt about climate change. Through a national survey of more than 2,100 adults, the two unearthed a striking fact: Americans considered TV weathercasters among their most trusted sources of global-warming information, ranking them behind only scientists and family members—and well ahead of the mainstream news media. Such credibility was rooted in several factors. TV weathercasters are often celebrities in their communities, and they’re likely to be the only scientists that their viewers know by name. Moreover, Americans have long depended on weathercasters when making decisions in their daily lives. “It can be everything from the mundane, ‘Do I take an umbrella to work today?,’ ” Leiserowitz says, “to the most existential, ‘Do I evacuate my home because of an oncoming storm?’ ”

Maibach recognized the significance of the finding. He was by then a leader in the field of public-health communications, a discipline that uses broadcast, digital, and other media strategies to improve the health of communities. After earning his PhD from Stanford in 1990, Maibach went on to help run public-service advertising campaigns addressing a range of health issues, including HIV/AIDS, cancer, and smoking. But it wasn’t until he participated in a study tour in the Italian Alps in 2006 that he decided to make climate change the focus of his career. During the trip, he attended lectures by respected European scientists about the ways that warming temperatures were affecting ecosystems. “For the first time, I really understood the enormity of [climate change] as an issue facing human civilization,” Maibach says. “And perhaps more importantly, for the first time, I understood the enormity of it as a public-health issue facing humanity.”

Thanks to his prior PSA campaigns as well as his academic research, Maibach knew that credible spokespeople would be the linchpin of a successful effort to address climate change. “If the messengers aren’t trusted,” he says, “there’s no possibility for effective education.” Once he saw the results of the 2008 survey, he knew he’d identified an influential group of voices.

Less than a week after the research was published, Maibach received an unexpected call. It was Joe Witte, the veteran on-air weatherman then working for WJLA’s Channel 7. “I’ve just read your survey report,” Witte said. “And you’ve taught me that I’m a trusted source on global warming.”

Witte placed the call during a period of professional self-examination. Then in his mid-sixties, he was winding down his career in TV and casting about for a new undertaking. Roughly two years earlier, he’d experienced something of an epiphany. From his home in Rosslyn, he was flipping among national news programs—on NBC, ABC, and CBS—when the networks began to address a new report from the Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change. On each of the three competing news programs, stern-faced anchors laid out the dire environmental warnings contained in the IPCC’s report, while producers rolled footage of polar bears ambling across the tundra or chunks of glaciers splashing into the Arctic Ocean. After 40 years in local television, Witte was struck by the disconnect between the footage and the audience. “I just thought, ‘Oh, my God—nobody is giving the local angle,’ ” Witte says. “ ‘These are great images, but they have nothing to do with the viewer.’ ”

Even Americans who accepted the reality of global warming tended to view it as a distant problem.

Though he didn’t know it at the time, Witte had hit on what was then a critical roadblock in the effort to address climate change. As Leiserowitz explains, even Americans who accepted the reality of global warming tended to view it as a distant problem. “Distant in time, as in the impacts wouldn’t be felt for a generation or more. And distant in space, [as in] this is about polar bears or developing countries, but not this country, not my community, not my friends, not my family, not me,” Leiserowitz says. “As a result, it just becomes psychologically distant—one of a hundred issues out there, and [people] don’t see why this is particularly important or urgent.”

Once Witte connected with Maibach, the two knocked around an idea. What if, they wondered, local TV meteorologists leveraged their platforms and credibility to show that climate change wasn’t some abstract concept involving glaciers but rather a here-and-now crisis whose impact was visible right in the daily weather report?

Maibach and Witte weren’t the first to discern the value of TV weathercasters in the arena of climate policy. Back in 1997, as the New York Times reported, President Bill Clinton summoned about 100 broadcast meteorologists to the White House for discussions with the administration’s top global-warming experts. Witte, who was among those invited, remembers standing in the security line outside the White House with a crowd of fellow forecasters. “It starts to rain,” he recalls, “and I think [only] two of us had umbrellas.” Once they were inside, the President—whose aides often lamented the lack of climate-change coverage on the evening news—told Witte and his colleagues that they were well positioned to shape public opinion on the issue. “You, just in the way that you comment on the events that you cover, may have real effect on the American people,” Clinton told the weathercasters, according to the Times.

The ingenuity of the White House’s approach may have backfired. That’s because while the Clinton administration failed to maintain an ongoing relationship with the weathercasters, advocacy groups that questioned the scientific consensus on global warming—such as the conservative Heartland Institute—seemed to recognize the wisdom of the strategy. “They actually ended up targeting the weathercaster community with climate misinformation,” Maibach says.

A surprising number of broadcast meteorologists were willing to believe the misinformation. That’s due in part to inadequate education—a 2016 survey of the American Meteorological Society’s members found that only about a third had undergraduate or advanced degrees in meteorology or atmospheric science—but it also reflected the influence of high-profile climate deniers within the field. Weather Channel cofounder John Coleman, for example, was an outspoken skeptic of global warming. By around the time Maibach and Witte joined up, only 54 percent of broadcast meteorologists believed in global warming, making them less accepting of the reality of climate change than the general public. “They felt [like], ‘I can’t forecast very well, seven days out—how can I predict something a couple of decades or 50 years out?’ ” says Mike Nelson, a weathercaster at KMGH-TV, the ABC affiliate in Denver.

In 2009, Maibach received a grant from the National Science Foundation to begin exploring his and Witte’s idea. Among their first priorities was to find a guinea pig—a TV weathercaster who believed in climate change and was willing to air one story a month detailing its impact on their local community. Though they found volunteers at stations in Denver and Detroit, they ultimately selected Jim Gandy, a respected meteorologist in the more conservative community of Columbia, South Carolina. “Because,” as Maibach puts it, “if you can make it work in a hard place, it has real potential to work in many other places.”

Gandy joined the effort at a time when the environmental-science community was under attack. He flew to Washington for his first meeting with Maibach and Witte in November 2009, just days after hackers had accessed a server at the UK’s University of East Anglia and released hundreds of internal emails. Climate deniers quickly seized on these messages, proclaiming—falsely—that they proved global warming was merely a concoction by corrupt academics. As the “Climategate” controversy gained national attention, Gandy began to worry that the Climate Matters experiment might alienate his South Carolina community—triggering a drop in viewership and an outflow of advertisers. “My reaction when all that occurred,” Gandy says, “was ‘I wonder what I’ve got us into.’ ”

Still, the group pressed forward. Gandy aired 13 segments on climate change over the course of 2010. Using peer-reviewed data, detailed weather maps, and high-resolution graphics—provided by Climate Central, a partner organization—he tied the nuances of Columbia’s weather to the broader issue of climate change. In the summer months, he showed his viewers how atmospheric changes were making the area’s temperature even more sweltering. On rainy days, he explained how global warming was affecting local precipitation levels. And in the spring, he demonstrated how higher amounts of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere were making poison ivy—a regional scourge—more toxic and abundant. “I had friends who were skeptical of climate change until they heard that one,” Gandy says. “It made them pause and think. And I said, ‘Well, if I can get you to pause and think, I have accomplished something.’ ”

To Gandy’s surprise, the segments on climate change didn’t generate the audience blowback he feared. In fact, at the conclusion of the yearlong experiment, his news director remarked, “I get more comments about what my anchors wear on the air every day than I ever got on Climate Matters.” Follow-up surveys soon determined that Gandy’s audience had come to see climate change as a more personally relevant issue than viewers of competing stations did. “As soon as we knew that,” Maibach says, “we got busy scaling it up.”

With his neat hair and straight teeth, Maibach could be mistaken for a weathercaster himself. A former competitive triathlete, he has a trim, wiry physique, and despite the gravity of the climate crisis, his personal disposition is unseasonably warm. His optimistic instincts were particularly useful during the period following the experiment in Columbia, when Maibach began working to expand the Climate Matters network to include meteorologists across the country. It was a daunting objective.

Of the roughly 2,000 broadcast meteorologists working in America in 2009, Maibach wasn’t able to find a single one who was discussing on the air the local impact of climate change. To convince them to start doing so, he partnered with nonprofit and government institutions that were highly trusted by weathercasters, including the American Meteorological Society, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and NASA. Meanwhile, Maibach and his partners launched an aggressive effort to educate meteorologists on the science of climate change. They hosted in-person trainings, ran remote webinars, recruited climate scientists to speak at weathercasting conferences, and connected meteorologists with global-warming experts.

When those efforts weren’t enough, the Climate Matters team got creative. In 2012, Maibach enlisted Sara Cobb, of George Mason’s Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution, to run conflict-mediation sessions with groups of weathercasters who held opposing views. Over the course of these sessions, Maibach and his colleagues came to learn that for many broadcasters, refusing to accept climate change had less to do with science than it did with interpersonal grievances. “[The climate-skeptical weathercasters] felt disrespected by the climate-science community,” Maibach says. Once he and his colleague were able to address these wounded feelings, the weathercasters became more receptive to the truth of climate change. Today, the share of climate skeptics in the broadcast meteorology community has shrunk to less than 10 percent, Maibach says.

At the same time, Maibach and his colleagues set themselves to removing the more practical roadblocks preventing meteorologists from discussing climate change on the air. As it turned out, one of the biggest obstacles had nothing to do with ignorance, ideology, or even fear. It was simply the number of hours in the day.

As weathercasters juggled the demands of the internet-age news economy—updating weather apps, posting videos to social media, blogging—many simply lacked the time and resources to produce credible climate-related segments. To address this, Maibach’s partner organization, Climate Central, agreed to furnish climate-reporting materials to all participating weathercasters. “We really did bring this weekly, localized climate-change science content to TV meteorologists around the country,” says Heidi Cullen, who was then the chief scientist of Climate Central. “So that required [us] to really build the infrastructure to analyze data, produce TV-ready graphics, and produce simple social-media content that folks could use.”

These reporting materials proved essential, says Paul Gross, a meteorologist at WDIV-TV, the NBC affiliate in Detroit. “Climate Central filled such an important gap, in providing high-resolution, on-air-quality graphics and the science behind it, so that we could communicate the science very, very easily,” Gross says.

They also helped meteorologists make the issue of climate change more personally relevant to audiences, says Matthew Cappucci, a meteorologist at the Washington Post, WAMU, and Fox 5. “Nobody cares that the oceans rise two millimeters a year. No one cares that the polar ice caps are [melting]—because none of us have ever been to the North Pole,” Cappucci says. “And suddenly you have Climate Central come in and they say, ‘Hey, we got the local trends for your city. You might be noticing XYZ—here’s why.’ ”

The data that Climate Matters provides is pulled from credible science-driven institutions such as NASA and NOAA, among other sources. Maibach insists that although George Mason is home to the Mercatus Center—the influential libertarian think tank that’s received generous funding over the years from entities linked to Charles and David Koch—his work has never been subjected to ideological pressure from university colleagues or administrators. “There are plenty [of people] who, initially at least, didn’t trust the work coming out of my center because they assumed that our whole university is an ideologically driven university,” Maibach says. “But it’s just not true.”

At the start of this year, Maibach and his team were providing climate-reporting resources—in Spanish and English—to nearly 1,100 broadcasters in just about every media market in the country. In 2014, TV weathercasters aired 69 segments on climate change. By the end of 2021, the figure had surged by more than a factor of 80, to nearly 5,600 in that year alone.

In 2020, Maibach and others published the results of a randomized controlled experiment involving TV-news viewers in Miami and Chicago. They found that when meteorologists incorporated the local impact of climate change into their weather reports, their audiences became more likely to accurately understand the issue and to grasp its effect on their daily lives. In a separate study published that year, Maibach and fellow researchers found evidence to suggest that Climate Matters’ efforts with meteorologists “may be increasing the climate literacy of the American people.”

Providing reporting materials is only one of the ways Climate Matters helps local weather teams. A few years back, Mike Goldrick, vice president of news at NBC4, was looking to expand the station’s coverage of the local impact of climate change. Goldrick invited Maibach and Bernadette Woods Placky, the current chief meteorologist of Climate Central, to the newsroom to speak with his meteorology department. Since that time, Climate Matters has furnished NBC4 with data showing that Washington-area viewers largely accept the reality of climate change, encouraged members of their news team to participate in a training program for climate reporting, and alerted the station to climate-related stories they might want to cover. “It was super-important to have them become part of our circle,” Goldrick says, “to be somebody that we can lean on when we had questions.”

Even as they’ve increased the airtime they’ve devoted to climate change, many of the weathercasters in the Climate Matters network have been surprised by how little negative attention these segments have generated. “I get some emails from viewers,” says Mike Nelson of Denver’s KMGH-TV, “[and] nine out of ten say, ‘Thank you—you’re the only one talking about this, and that’s one of the reasons why we watch you.’ ”

This experience squares with a body of research suggesting that climate change isn’t nearly as polarizing as it’s often portrayed. In a survey conducted in September 2021, Maibach, Leiserowitz, and others found that only 19 percent of Americans were either doubtful or dismissive of human-caused global warming, while a far greater share—58 percent—were either alarmed or concerned. “The narrative changed a long time ago, but the media was following an older narrative,” says Placky. “[The public’s] interested. They have questions, and people aren’t answering their questions.”

Climate change isn’t nearly as polarizing as it’s often portrayed. In a 2021 survey, only 19 percent of Americans were either doubtful or dismissive of global warming

Not all viewers have been so receptive. In June 2021, Chris Gloninger left his Boston station to become chief meteorologist at KCCI, the CBS affiliate in Des Moines. Upon arriving in Iowa, he began using the Climate Matters materials to show his viewers how climate change was affecting the local weather, just as he’d done at his previous job. The reports sparked disapproval by some members of this more conservative community. “When I was in Boston, [I] was preaching to the choir,” Gloninger says. In Iowa, however, he was “in the lion’s den,” as Gloninger puts it.

Earlier this year, he received a terrifying email: “What’s your address, we conservative Iowans would like to give you an Iowan welcome you will never forget, kinda like the libtards gave JUDGE KAVANAUGH!!!!!!!” The threat was a reference to the June incident in which a California man was charged with attempted murder after he was arrested near Supreme Court justice Brett Kavanaugh’s home with a handgun, zip ties, and other ominous materials. Gloninger filed a police report. Law enforcement subsequently identified the man who had made the threat and, according to court records, charged him with third-degree harassment, a misdemeanor.

In the wake of the incident, KCCI’s management added new security measures at the station and provided Gloninger with security guards when he was reporting at the state fair. Still, the experience left him unsettled. “There isn’t a time in the day where I don’t think about it,” Gloninger says. Despite it all, he continues to make use of the Climate Matters materials by regularly airing reports on climate change. “Unless there is a tornado touching down or a major hurricane making landfall or floodwaters inundating a community, there isn’t anything that’s more important than what we’re doing [on climate change] day to day,” Gloninger says. “That should be all of our responsibilities as broadcast meteorologists to be doing this, especially when the weather is quiet.”

That’s precisely how Maibach sees it. When he counsels weathercasters on how to handle negative blowback from viewers, he provides them with research data showing that the most hardcore climate deniers—“dismissive,” he calls them—represent just 9 percent of the American public. “So it’s absolutely a foregone conclusion that you will hear from them,” Maibach says. “But if you don’t speak, if you don’t educate your viewers about the local impacts of climate change, you’re self-censoring to keep them placated—and that’s not serving your audience.”

Even as he continues to increase his network of meteorologists, Maibach is working to expand Climate Matters’ reach by teaming up with a different set of messengers. A few years ago, he found survey data indicating that while many local print and online journalists were eager to tackle climate change, most didn’t feel they knew enough to cover the topic. “It just became obvious to us,” Maibach says. “This is the next group of journalists that we can work with to help them really lean into this story.”

Since that time, through a partnership with the Local Media Association, the Climate Matters team has provided reporting resources to community journalists across the country. As is the case with the weathercasters, the goal is to help them show readers how climate change isn’t a far-off curiosity but an ongoing crisis they can see all around them.

Whether it’s on the local weather report or in the community newspaper, the efforts of Climate Matters’ affiliated journalists will only grow more important in the future. That’s because even in the most optimistic scenarios, global warming is expected to increase significantly over the coming decades. The result is likely to be more flash floods, longer droughts, bigger wildfires, additional heat waves, and more intense storms. On-air meteorologists and local-news reporters will be uniquely positioned not only to educate the public on the relationship between climate change and extreme weather events but also to help them navigate life in a warmer world. “What do we want to do to protect our infrastructure [and] to protect our people’s health? . . . How do you create a climate-ready America?” Maibach says. “It absolutely begins with helping people understand the reality of the problem they’re dealing with, so that they can make better choices about ways of dealing with those problems.”

This article appears in the November 2022 issue of Washingtonian.

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)