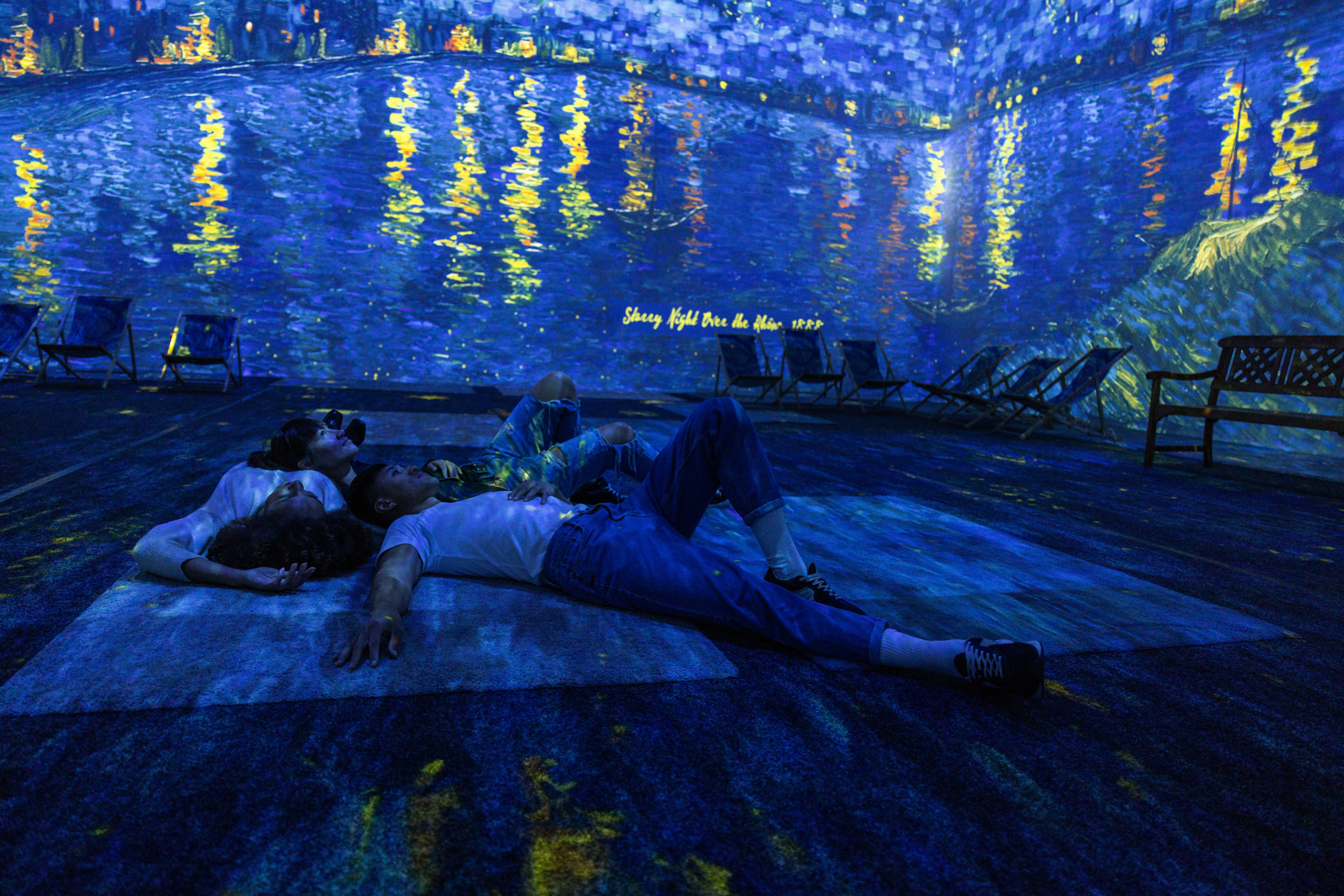

The last time I spent so long unable to peel myself off the floor was during a heinous bout of food poisoning in college. But here I was, lying on a furry mat inside a chilly 20,000-square-foot industrial cavern in a former Big Lots! in Brentwood, staring at the incandescent orbs of “The Starry Night” revolving around the main room at “Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience.” Other people were camped out on their own mats and lounge chairs, watching and vibing, letting giant 360-degree projections of Vincent van Gogh’s paintings wash over the room. This kind of feels like a brain massage, I wrote in my Notes app. Very soothing. Am I relaxed? At the end of the roughly 30-minute show, no one moved—and I realized that I didn’t want to leave, either.

View this post on Instagram

My main reason for being there was, I imagine, the same as everyone else’s: I had been worn down by the relentless “buy tix now” pleas in my Instagram feed. In recent years, so-called immersive experiences have exploded in popularity worldwide, with many making their way to Washington. There are digital-art exhibits such as “Mexican Geniuses: A Frida & Diego Immersive Experience,” which opened in August in Brentwood. There are pop-culture-centric experiences in which you get to inhabit the fictional worlds of TV hits like Bridgerton, Friends, and The Office—as well as book-and-movie-inspired ones such as the wildly popular “Harry Potter: A Forbidden Forest Experience,” a nighttime woodland-trail journey that opened in Leesburg in October. There are educational experiences, like National Geographic’s “Beyond King Tut,” on display until February. There are even “pop-up bar” experiences that are light on education and heavy on comedy and cocktails, including one inspired by The Little Mermaid.

The last of these—which came here last winter and promised a “spellbinding journey to the underwater kingdom”—was my first immersive experience. It left me skeptical. I had pictured it as Sleep No More meets Splash Mountain in a speakeasy, but the vibe was more high-school musical meets dinner theater: While actors belted about deep-sea love and loss, I drank suspiciously strong deep-sea potions from a treasure chest and scarfed down gas-station-quality sandwich rolls (wait, were they supposed to be sushi?!) to lessen the effect of said potions. When it was over, I felt far from brain-massaged. More like swindled and tipsy. Still, I kept sampling immersive experiences, walking over hot coals like Pam from The Office and putting on virtual-reality glasses to float away into the afterlife with the souls of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera as they narrated their rocky love story. I figured there had to be a deeper reason these experiences were in demand right now, at this particular cultural moment.

It was at van Gogh that the answer dawned on me. More than 5 million people in the world have visited this experience, with more than 550,000 tickets sold in Washington, and so many have described it as cathartic. In my supine state, it occurred to me that immersive experiences are basically mass group therapy, a salve for the stress of our never-really-over pandemic, increasingly worrisome politics, and everything else that in recent years has left us feeling isolated and burned out. As I lay there watching the petals of “Almond Blossom” fall gently to somber orchestral music, I felt relaxed, not anxious, for the first time in seemingly forever. I left feeling rejuvenated.

Vinita Mehta, a clinical psychologist in Dupont Circle who specializes in depression, anxiety, and life transitions, confirms my mass-therapy hypothesis. “Think of rocking a baby or the steady beat of a metronome,” she says, adding that getting lost in the colorful patterns of projected art can be a powerful form of stress relief. “Repetition can provide predictability, containment, and structure as we come out of a collective trauma.” It’s about temporarily restoring mental order in a messy world.

Mehta believes that these huge rooms with wraparound projections became more popular as pandemic restrictions lifted in 2021, because they provide us with a way to “be alone with others,” sharing a common perspective without having to do any pesky talking. This type of environment provides a satisfying middle ground between going out and being social, which some of Mehta’s clients say they no longer have much “endurance” for (honestly, same), and staying home, which many people are tired of (honestly, same). I felt this powerfully at “Mexican Geniuses,” where families hung out on beanbag chairs, watching as Kahlo’s self-portraits and Rivera’s murals danced all around us. We were silently united by the tragedies of Kahlo’s life, and by her and Rivera’s political ideals and tumultuous relationship.

Laura Miles, an art therapist at Alexandria Art Therapy, says she had just gone through a breakup when she visited her first immersive exhibit in 2018. It was Gustav Klimt at the Atelier des Lumières in Paris, where you can step into iconic, moving paintings such as “The Kiss.”

“To say that I felt overwhelmed with emotion is an understatement,” she wrote in an e-mail to me. “I stayed over four hours and cried almost the whole time. I got goosebumps on my scalp, something that’s only happened a handful of times for me.” Her experience isn’t singular: On social media, viewers regularly describe these shows as “stunning” or “breathtaking.”

Since that Klimt show, Miles has seen three different immersive van Gogh exhibitions in the US. (There are more than 50 immersive van Gogh exhibitions from five different entities in the world right now, thanks partially to an influential scene in the Netflix series Emily in Paris.) As Miles was writing to me, she was in Paris again, having just revisited the Atelier to see shows featuring Paul Cézanne and Wassily Kandinsky. Like Mehta, she thinks the feeling of being “immersed” in a work of art can be therapeutic.

“The experience of living inside a work of art is, for me, a unique opportunity to experience a piece on a multisensory level,” Miles says. “The images move around you in fluid ways, the music is chosen carefully to enhance the feeling, and you let go of everything that doesn’t matter in that moment. Integrating the senses in such a way can help us feel more connected to our internal world and our external one—like that feeling of looking at the stars and feeling both minuscule and infinite.”

In this moment, it makes sense that people are demanding chill, contemplative time—a “third space” to be alone with our thoughts, and perhaps even with the new ways we’ve started to see ourselves as the pandemic has shifted so much of life as we know it. When I asked whether stress relief was part of the puzzle in planning these experiences, Francisco Hein, cofounder and chief marketing officer of Fever—the global entertainment company that promotes many of them—simply said: “The journey that you described is intentional.”

Immersive experiences are as old as history, with no one way to define them. There’s evidence that prehistoric people were lighting caves with fire to create a moving effect with animal paintings. In the 18th and 19th centuries, before the rise of motion pictures, phantasmagoria was a type of theater that used “magic lanterns,” or early projectors, to display spooky images. Lean into the concept, and amusement parks, haunted houses, and video games all qualify as immersive, too.

The current wave of experiences can be considered tech-driven, simplified cousins to digital-art installations like those at DC’s Artechouse. You can also see the early roots of today’s experiences in the work of artists such as Yayoi Kusama, who has been creating immersive art installations since the 1960s. (Kusama has spoken candidly about her work being healing and therapeutic when dealing with her mental illness.)

Digital immersive experiences are seeping into museums looking for new ways to draw in audiences. Some people have argued that they help democratize art for marginalized populations who may not feel comfortable in a museum environment. In 2017, Kusama’s “Infinity Mirrors” brought 160,000 visitors to the Hirshhorn Museum and was quite possibly one of the most Instagrammed art exhibits ever, with its dotted pumpkins and twinkling lights taking over feeds for months. Her “One With Eternity” exhibit, which included a psychedelic mirror room called “My Heart Is Dancing Into the Universe,” took over the Hirshhorn this year after a long, pandemic-related delay.

View this post on Instagram

Janet Kraynak, an art historian and professor at Columbia University, questions both the artistic value of Fever-style immersive experiences and the notion that they make art more accessible to a wider range of people.

“They’re not actually providing the viewer with any real knowledge or information about the art, its importance, and its history,” Kraynak says. Digital experiences, she adds, also can flatten the significant physical aspects of an artist’s work, such as Rivera’s large-scale murals or van Gogh’s revolutionary use of color and distinctive impasto brushwork. “In transforming paintings into interactive screens, they decontextualize the art while condescending to the audience.” (Art critic Ben Davis put it another way, writing: “Van Gogh without the impasto is like, I don’t know, facetuning Frida Kahlo to give her Lily Collins eyebrows.”)

I didn’t think I would enjoy stepping into “The Office Experience” as much as I did stepping into “The Starry Night.” Like many card-carrying, slightly embarrassing millennials, I grew up watching the longrunning television series. Still, I had doubts about how effectively it would translate to a live experience. I mean, the actual world of The Office is pretty boring. I’ve been to Scranton: There’s a mall. Would I have to answer phones for a midsize paper company? Would I have to sit through the entirety of Threat Level Midnight? Would I get to feel God in a Chili’s? (Oh, please say yes.)

Unfortunately, I did not feel God in a Chili’s, although that still ranks in the top five of my life goals. However, I did spend a remarkably carefree afternoon reliving all my favorite moments from the show and playing around like a big kid in a ginormous space behind the ornate facade of the historic former Woodies building, where the production company Original X* had recreated the universe of the Dunder Mifflin Paper Company. At first, I was overwhelmed because it was a lot: The main draw is a huge replica of The Office set, complete with character-specific Easter eggs such as Dwight’s famous Jell-O stapler in his desk and hilarious voice messages; it’s tempting to open every single drawer and pick up every single phone to take in all the details. But then I sort of surrendered to it all (including Threat Level Midnight playing on a small screen), and it ended up feeling just as therapeutic as the visual-art experiences. I stepped outside feeling disoriented, surprised that it was still light and that I was in DC and not Scranton—but in the best way.

Other attendees confirmed my hunch that the point here was letting us indulge in nostalgia for a beloved show, a feeling that in itself is therapeutic. So is the fact that the experience makes the show tactile following months of working from home, posting on social media, and binge-watching Netflix—all of which Mehta says may start to feel like a “sensory-deprivation tank” after repeated exposure. Today, we need to touch things, not just look at screens. At one point, I found myself picking up Pam’s phone at the reception desk: “Dunder Mifflin, this is Natalie.”

I stepped outside feeling disoriented, surprised that it was still light and that I was in DC and not Scranton—but in the best way.

“Giving guests the ability to step into a set that they know like the back of their hand, and live it and walk it—I think there’s something really cool about that,” says Terry McMahon, senior creative director at Original X Productions, which was also behind a Friends experience. “You’re walking into this thing that you’ve probably spent tons of hours watching on TV.” The creators worked on the experience for an entire year before it launched in its original location, Chicago, and they even consulted with NBC to make sure everything looked and felt as authentic to the show as possible.

View this post on Instagram

That emphasis on the physical—and on being here now—sets today’s experiences apart. In 2017 and 2018, a wave of pop-ups emerged that seemed engineered to create picture-perfect Instagram content. One of them is the Museum of Ice Cream, where you can snap a photo of yourself swimming around in a candy-colored ball pit; another, Rosé Mansion, allowed attendees to take a selfie lying in a bathtub of rose petals. These “experiences” were mostly about posting on social media, which in turn helped promote them to new customers. The New York Times dubbed this a “masochistic march through voids of meaning,” which isn’t completely off-base. I would call the sensation evoked by these experiences a brain-pummeling, rather than the sought-after brain massage.

Since then, however, the Instagram aesthetic and the platform’s algorithm have changed so that pretty, posed, and pastel images no longer feel relevant. At The Office, there were a few “suggested” social-media moments, and staff was on hand to help with photos. Yet most of the content creation was personal, not meant for mass consumption or eliciting maximum FOMO. Yes, you can capture yourself playing Dunderball, goofily dancing down the aisle at Pam and Jim’s wedding, and even making your own Office-style confessional—but if your hair is out of place or you’re laughing like a hyena, then all the better. The people I talked to afterward said they cared more about enjoying the experience in the moment and that they were going to send pictures and videos around to close friends. They didn’t plan to post them widely.

Just as our prehistoric ancestors moved on from cave fires, audiences will eventually move on from today’s 360-degree art and touchable pop-culture immersion experiences. “I think we have a deadline with these kinds of experiences, probably five years, that’s it,” says Bernardo Noval, founder and CEO of Brain Hunter, which created “Mexican Geniuses” and brought it to the US. The next step? Noval says it could involve the metaverse, the virtual-reality world that Meta and other tech companies are attempting to bring into existence via VR goggles, billions of dollars in R&D spending, and convincing our bosses that the latest cutting-edge technology for meetings involves giving the avatars from Wii Sports fully animated legs. On the other hand, there are also signs that audiences are tired of everything being so tech-forward: Old-school arcades, for example, are a big feature of the Stranger Things experience, now running in Atlanta, Los Angeles, and London.

Whatever shape or medium immersive experiences take on next, they’ll continue to provide entertainment and escapism. Recently, I found myself scrolling through the Fever app in the middle of the night, sending immersive-experience links to friends and family, and planning upcoming weekends centered around them. Maybe I’m still chasing that feeling of renewal. What I know is that I’m not going for particular brushstrokes or pure pop nostalgia. At their heart, immersive experiences aren’t really about those things. They’re about us. At their worst, they’re an excuse to meet over cocktails with friends IRL. At their best, they let us step outside ourselves and, hopefully, make inroads into healing our individual and collective traumas. One day, we might get sick of digital-art exhibits, or no longer watch The Office. But the need to be alone together, the wish to lose ourselves in a fictional world for an afternoon, the desire to leave the house while still feeling at home—these are timeless human impulses. And, just kidding, we’ll be watching The Office until we die.

This article appears in the December 2022 issue of Washingtonian. *An earlier version of this article referred to the production company as Superfly X, but the company has changed its name to Original X Productions.