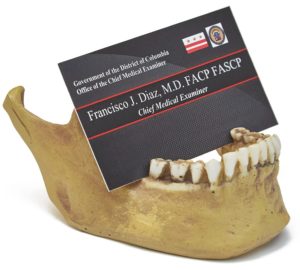

If, God forbid, you should die a non-natural death in the District of Columbia—homicide, suicide, overdose, car crash—you will likely end up in the care of DC’s chief medical examiner, Francisco Diaz. A tall man in a dark suit, Diaz is an expert in autopsies: He says he’s probably performed 10,000 of them in his career. His desk is a mess of plastic skeletons and autopsy reports, and his business-card holder is a model of a human jaw. Diaz’s office, in a glassy building just south of the Mall, sits above a warren of sterile-looking rooms—an autopsy facility with theater seating for teaching, a biosafety area where pathologists in protective suits work on infectious corpses, and a cold room where the bodies are stored.

A native of the Dominican Republic, Diaz came to the United States in 1995 for specialized training in pathology and decided to stay. He has since worked for medical examiners’ offices in both Philadelphia and Wayne County, Michigan (which includes Detroit). In 2017, Diaz became the District’s deputy chief medical examiner and medical director, and he took over as chief in January 2021. We spoke about his difficult work during the Covid pandemic, how he handles politicized cause-of-death calls, and why TV depictions of autopsies are so bad.

How did you get into this line of work?

I was always attracted to autopsies. They’re a vehicle to advance science. If you look at the tradition of performing autopsies, I think it was paramount to advancing the knowledge of anatomy and physiology, surgery, internal medicine, and how the organs work. So ever since I was in medical school, I wanted to become a forensic pathologist.

What do you like about forensic pathology?

I think it’s more interesting than any other medical specialty. Some are more routine—day in and day out, they see basically the same thing. In forensic pathology, you have a constellation of things. If it’s not homicides, it’s something that could be a potential homicide. Is it a suicide or not a suicide? At age 38, a patient collapses on the street; at first you think it was a heart attack, but it turns out to be a brain tumor that the patient was never diagnosed with. So it brings challenges.

You were working in DC for all of Covid. What was that like?

It was an experience that is difficult to put into words. At least at the very beginning, you didn’t see a light at the end of the tunnel. In a single day, you are used to having six decedents coming in. Then [when the pandemic hit], the next day there are 25. And the next day, 27. The next day, 40. We were here every single day—every single day—because that’s the only way you can manage.

And, of course, we work with human beings. People [who work in the medical examiner’s office] are concerned if they’re going to get contaminated. At the very beginning, we didn’t know—are the decedents contagious or not? They are not. But that’s a concern that we had.

What was the day-to-day work like?

When people were pronounced dead at hospitals or died at home, we went to pick up the decedents. We have a Biosafety Level 3 suite, and that’s where we did the swabs [to test for Covid]. We opened an alternate morgue site that had refrigerated trucks for a few months. It was very intense. It took all the effort of each and every employee here for that period of time. As an agency, I think we did a remarkable job. Because if you see what happened in other places, you will see how decedents were accumulating in the hallways, in storage facilities, even in U-Hauls. And that didn’t happen in the District at all. There were no mishaps—no releasing the wrong body. We’re very proud of the work of each and every employee. They put their heart and soul into it. Everybody here was committed to the mission.

Every once in a while, you have to make a call that’s politicized—like determining the cause of death of Capitol Police officer Brian Sicknick, who died after protecting the Capitol on January 6. I’m curious what it’s like to be making a medical call when everyone else is thinking about it politically.

As you stated correctly, it’s a medical call. It’s for the purposes of public-health statistics. As a medical examiner, you cannot be thinking all the time that if I do X determination, then there’s going to be fallout. It comes with the territory.

That’s what makes forensic pathology, or being a medical examiner, stressful for a lot of people. Because as opposed to other medical fields, there is no positive feedback. So you can be a surgeon and work a million hours a week, but you may get the feedback “Thank you, doctor, for saving my brother’s life.” As a forensic pathologist, you don’t get that call. You’re not going to tell me, “Great job you did on the autopsy of my Uncle Joey.” You’re not going to say that.

What kind of feedback do you get?

More often than not, it’s negative. If I decide an autopsy has to be performed, the family may be up in arms: “You’re going to cut her up!” Or the opposite happens—if I decide an autopsy is not necessary, they’re not happy, because they want X or Y. If we go and testify, the prosecutor would like you to say something that benefits them, but the defense attorney would like you to say something that benefits them, right? So we are in the middle of all that fire. And if you are not [focused] in your mission, that lack of positive feedback can wear you down.

I’m curious about TV and movie depictions of forensic pathology. Are there any that stand out as particularly accurate or particularly bad?

In my opinion, they are all bad. They have one good thing, which is that they get young people interested in science. But whatever they portray is not accurate.

What do you see that isn’t accurate?

Like, everything. So I don’t watch them unless I want a good laugh. A crime happens, and they solve it within 40 minutes—they have instantaneous answers for everything. You know, like, you were here, you left a hair there, you put it through a machine, and then you have answers. And depicting an autopsy—I mean, they just put an electric saw through the hair! You need to part the hair first. But they just put the electric saw right there. Imagine if you have a lot of hair—there’s no electric saw that is going to go through that. Just an example.

I read somewhere that pathologists sometimes catch colds from corpses. Is that true?

No, dead people do not breathe, so that means they don’t aerosolize. What you can catch is things from the blood, if you cut yourself. Let’s say you draw blood and then you puncture yourself. You have a chance of contaminating yourself.

You could also get tuberculosis from a decedent, because the electric saw could aerosolize things. So that’s why we don’t use electric saws to cut the ribs—we use shears. Meningitis you can get. Meningitis is contagious. So if you open a cranial cavity and there is bacterial meningitis and you’re not using the proper protection, you can get it.

Have you ever cut yourself?

I have never cut myself. [Knocks on the wood table.] I pay attention. When I was very young, a surgeon told me, “I don’t respect pathologists, because they don’t respect the scalpel.” And that was absolutely true. Pathologists talk with a scalpel—like, hey. [Waves his hand around like he’s cutting wildly.] But surgeons have an absolute respect for the scalpel, and that’s the best advice I’ve ever gotten. I always know where my sharps are. They are not under something. That’s where people get cut—they’re going to grab something and boom!

Is there any case that stands out as being the most unusual in your career?

Yes, I had a case that was very unusual. In 2012, I was the medical examiner that responded to the Detroit Metropolitan Airport because different federal agencies—customs, the CDC, and the FBI—were following a number of people that were trafficking in body parts.

Oh, like selling organs?

Selling body parts, not organs. Like heads, hands.

What’s the market for that?

For educational purposes.

Oh.

The reason we were called was that eight heads came from Israel. You’re too young, but there was a movie that wasn’t good with Joe Pesci. It’s called 8 Heads in a Duffel Bag. Well, that’s what we found—there were eight heads in containers. Do you know what he used as a preservative? It was mouthwash. That’s why they were decomposing.

We took jurisdiction of the heads, and I thought that was going to be the end of it. But the FBI followed up, and [in 2013] we were part of a team that raided a warehouse in Detroit. At the end of that operation, we recovered 1,200 heads and other specimens. That involved millions of dollars, because a body could sell for maybe $100,000. That’s what I was told.

Wait, were medical schools buying illegal body parts?

They didn’t know they were illegal, or that they were acquired illegally. A lot of [the specimens] were contaminated with HIV or hepatitis. The whole process took years. It was a huge operation. That was probably the most interesting case I’ve been involved with, because I wasn’t expecting that.

You regularly deal with awful stuff. Does that change how you see the world?

It does, in a way. You have what the French call “professional deformation.” That means that you see the world based on your profession. As a physician, you look at somebody and say, “Well, this person’s color is not good. This person may have liver disease.” So that’s an example. I tend to view the world like that.

It’s difficult to attract people to the field, because some people cannot do autopsies day in and day out. I mean, I cannot watch movies with torture. I don’t like horror movies. Some people that want to do this work—they think it’s cool. But it takes a toll. It changes you.

This article appears in the December 2022 issue of Washingtonian.