Back in January, the National Security Agency’s museum sent out a press release about an upcoming Valentine’s Day exhibit. Sorry, what? The NSA has a museum? For decades, the US government wouldn’t even acknowledge the agency’s existence, but now its press officer was beckoning me to Fort Meade.

The advertised exhibit involved “sweetheart codes”: love letters from American soldiers who wanted to “express their innermost personal thoughts, sometimes in the most passionate of terms” while also hiding their kinks from the postal censors. Apparently, the GIs would encode all the good parts for their girlfriends back home to decrypt.

Filthy historical letters sounded intriguing, but the real draw was the NSA. Like many Americans, I had no idea what the agency was up to besides lethally pissing off Edward Snowden and reading all my emails. So I let the press guy know that I would come, and that I was bringing my husband, too. This would be a work assignment and our Valentine’s Day date. What a joy to get credit for both.

Four days before Valentine’s Day, while driving to Fort Meade, I explained the sweetheart codes to my husband. Then I made what was perhaps a cruel joke: that maybe when he acts cold and aloof, it’s simply an encrypted expression of love. Chuckling, I paused to write this down, and Zak began to look worried, intuiting that nothing he said was off-the-record. When I asked what’s the matter, he wisely declined to answer, lest I write about that, too.

This struck me as a productive response. “Isn’t it interesting,” I said, “that you stridently object to me creating a record of our private conversations? I mean, that’s the whole problem with the NSA.”

“Yes,” he said, dispirited. “You have found an interesting echo that I’m sure you will write about.” He turned up the radio and theatrically refused to speak until we arrived.

The NSA museum is not called “The NSA Museum”—it’s the “National Cryptologic Museum.” That framing does a lot of work. “Cryptology” foregrounds the NSA’s fun parts (the making and breaking of codes), while burying its uglier aspects (the warrantless surveillance of Americans). The whole museum, in fact, is an NSA charm offensive: jokey wall text, a gift shop that sells NSA-branded “secret sauce” for barbeque, some kind of DARPA-funded video game car that emits an ethereal light. When we arrive, my husband and I wander the museum saucer-eyed before the press officer locates us for our tour.

Leading the tour is the museum’s director, Vince Houghton, a military historian who’s just come in from having a smoke. Though he’s an NSA employee, Houghton looks more like a basketball coach: sneakers, artificially weathered jeans, an oversized polo. Houghton is a serious person—a veteran, a scholar, the author of two books on intelligence—but he has a flair for drama. With the energy of a golden retriever, he describes the sweetheart codes exhibit as “literally about love, about sex, and about other things that are very not-NSA.” But first, he wants to show us everything else.

The National Cryptologic Museum is full of objects that not many people have seen: machines that were only recently declassified, artifacts that sat for decades in storage. “We have a warehouse,” Houghton explains. “It looks just like the one at the end of Raiders of Lost Ark—floor-to-ceiling crates in a dusty government building, two rows over is all the classified stuff.” During Covid, the staff inventoried the warehouse and found many of the items now displayed.

We begin with the world’s first known cipher device—a wooden wheel that may have belonged to Thomas Jefferson—which Houghton describes as “old as hell.” Then we wander past the Enigma machine used for Hitler’s communications, the two gadgets that made up the Washington-Moscow hotline, and the secure phone from President Reagan’s limousine. I pause before a mangled metal cube the size of a box of butter; it’s an NSA-designed communications system, recovered from the wreckage of space shuttle Challenger.

Despite the watchful eye of the press officer, Houghton is having oodles of fun. He loves the eccentricities of historical codebreakers, like the WWII naval officer who would come to work “looking like Hugh Hefner, walking around talking to admirals in a robe.” Modern cryptologists apparently have similar habits; the NSA, Houghton explains, does not have a dress code, so “supervisors can’t tell their people what to wear.” “You’ll walk around and see people in suits,” he says, “but you’ll also see people in flip-flops and Misfits T-shirts and mohawks or bathrobes. We have people you would expect to see at a Bad Religion concert, or at a Phish concert, but without the drugs.” When the PR guy interjects, I assume it’s to correct the record—but, no. He wants me to know that “some guy had on a kilt the other day.”

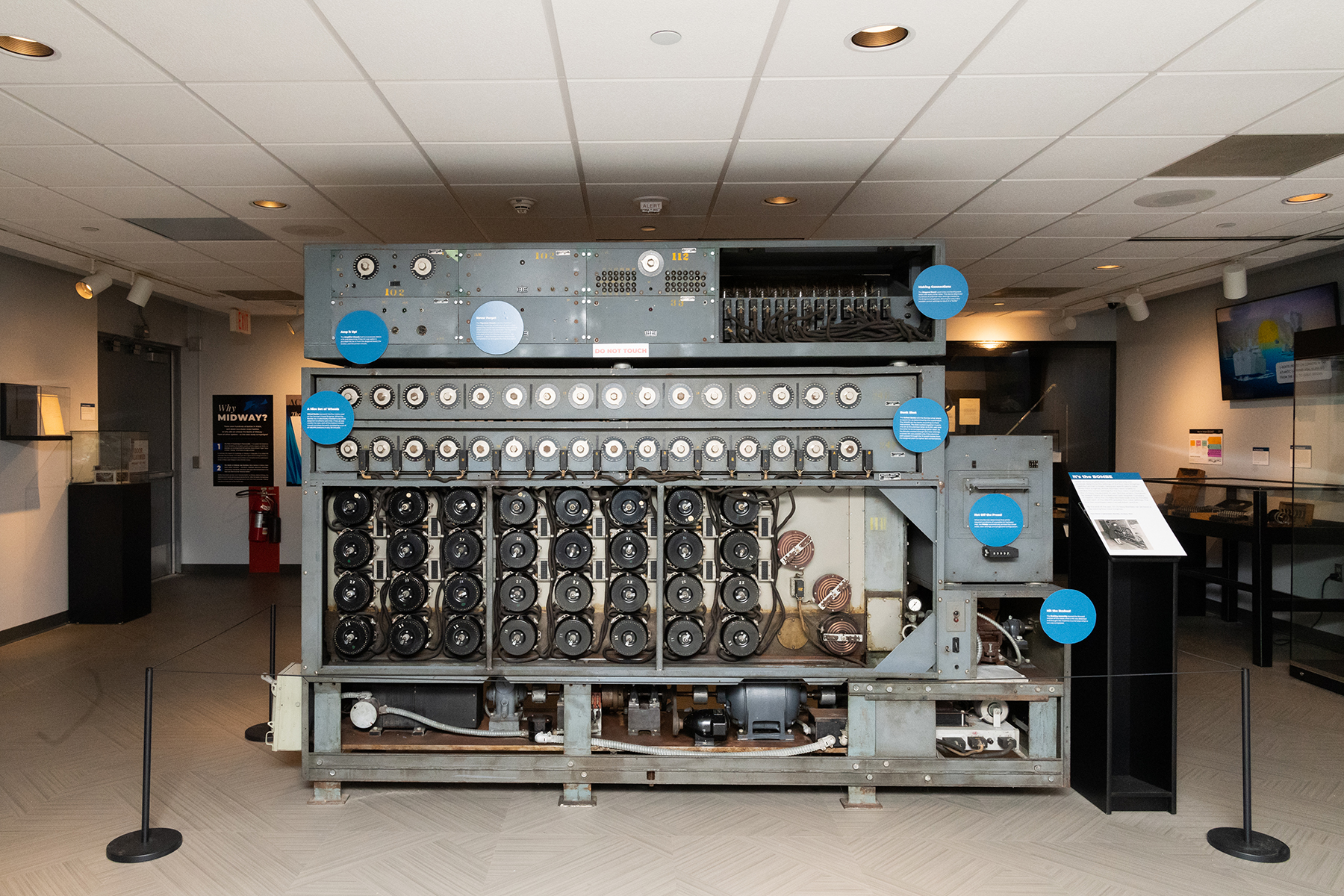

Houghton is an excellent tour guide. He has a televangelist verve that brings esoteric machines to life. I stand for a while before a recently-retired NSA supercomputer that looks like a panic room from the Matrix. Nearby are the hulking machines that once produced the nuclear codes. The star of the show is a WWII-era codebreaking machine called a “Bombe,” which ran 24 hours a day in a warehouse on Nebraska Avenue. Each day, this Bombe and her brethren would crack a new four-rotor Enigma code, enabling the slaughter of a whole lot of Germans in submarines. Without this machine, Houghton thinks the war might have ended differently; “most of Europe would still glow in the dark.”

Perhaps this doesn’t sound like an ideal Valentine’s date, but I haven’t yet described the activity stations. At one, Zak and I dip toothpicks into a clear jar labeled “invisible ink” and etch messages onto scraps of paper. Then, we reveal those messages by coating a Q-Tip with purple liquid and rubbing it across the clear ink. It’s a blast. Later, he and I stand at two separate Enigma machines, encrypting messages to each other. When I punch his coded message into the typewriter keys, letters light up to reveal the decrypted word. He has simply written “Peep.”

I’m aware that this is NSA propaganda, a bacchanal of over-the-top military machines from generations of lavish defense spending. But I love the National Cryptologic Museum. Where else could I peek at the innards of a supercomputer then examine a handwritten cipher of yore? I learn that NSA intelligence contributed to the Bin Laden raid, and that the agency encrypted communications for the space program. And the terminology is intoxicating: “teraflops of computing power,” “Minuteman III nuclear silos,” “quantum encryption,” “exolinguistics,” “laser communications.” I know that “intoxicated” is how the NSA wants me to feel, but credit where credit is due.

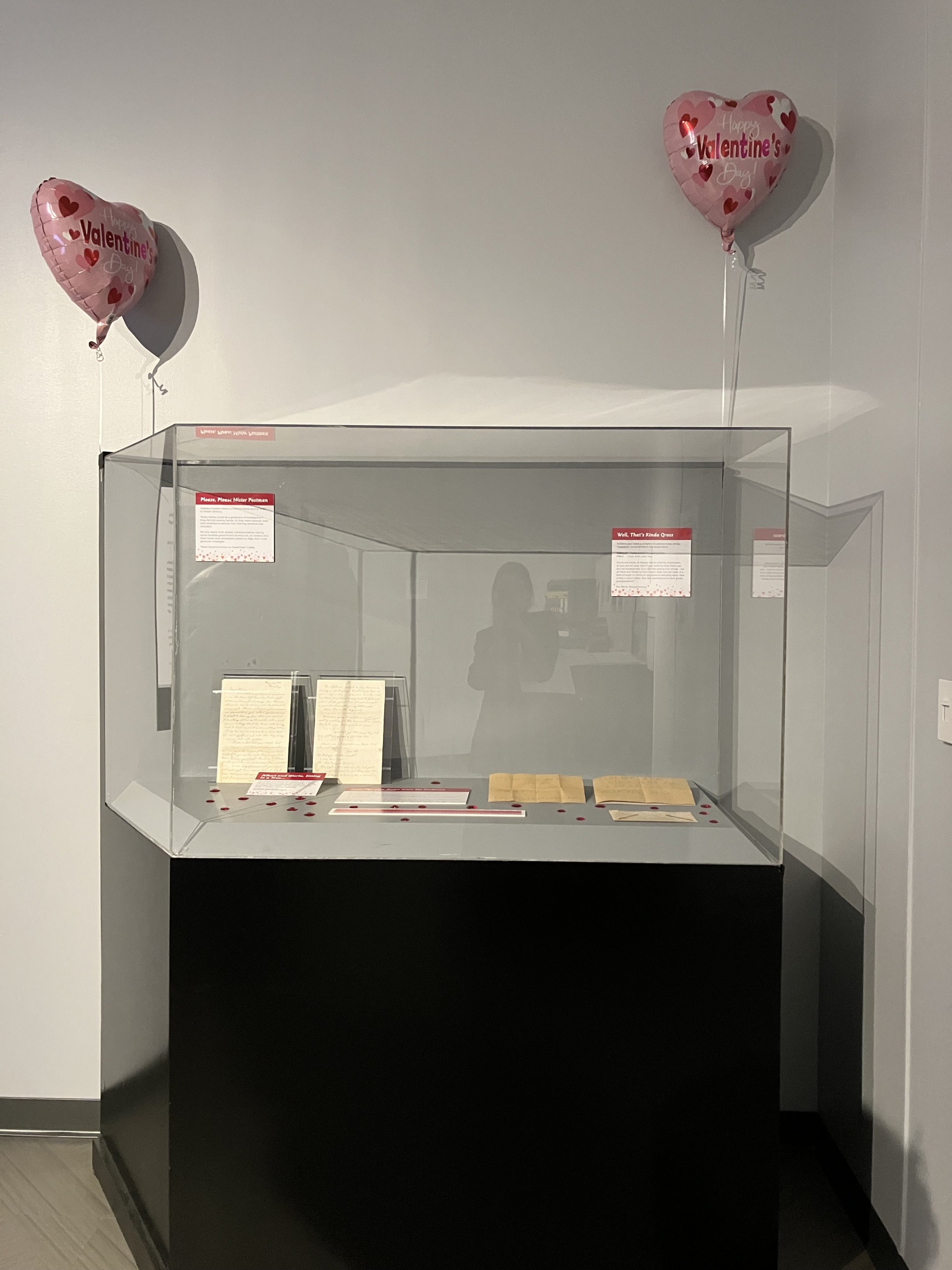

Finally, we arrive at the sweetheart codes—the exhibit we’ve come here to see. “Exhibit,” though, is sort of a generous word; it’s one medium-small display case, flanked with two heart-shaped balloons, that holds a single G-rated letter from the Second World War. In it, a soldier named Al writes to his girlfriend, Gloria, explaining the cipher they’ll use going forward. In vain, I search for the smut—the spicy letters that the press release promised—and alas, they are not on display. “We’re a family institution,” the wall text scolds, “so you are on your own if you want to look them up.”

Another thing that’s not on display is whatever the NSA does now. This makes sense—the museum’s focus is historical, and the agency’s present-day work is classified. But from what I gather, our nation’s army of bathrobed cryptologists intercept foreign communications to thwart terrorists. I’m not going to quibble with that.

Where I’m skeptical is the domestic side: I tend to enjoy my civil liberties, and I don’t love that American tax dollars once funded a communications dragnet into which our most innocuous calls could be swept. But I’ve come here to learn about ciphers and romance my husband during business hours, not to cross the NSA, so for most of the tour, I manage to stay out of trouble. Even when Houghton describes the agency as a “a pack rat in many respects, in that they keep stuff,” I repress the urge to ask about my instant messages from 2003.

Then we start talking about movies. My husband asks which ones get the NSA right, and the question lights Houghton up. “The problem that we run into is that NSA is behind the other agencies in their public relations,” he explains. “I mean, CIA had Zero Dark Thirty. They basically co-wrote that movie. The Navy had Top Gun. At any one point, there’s, like, seven FBI shows on TV. But NSA’s portrayal in movies has been Enemy of the State. And it’s NSA running around killing people in the United States.”

This strikes me as a little beside the point. The American people don’t mistrust the NSA because of Enemy of the State—we’re mad about the illegal domestic spying. But when I raise this issue, the NSA’s public relations circuitry begins to smoke. After a short pause, the PR guy says, “Why don’t we move out of this room.” A tour group of retirees is moving through, and he clearly doesn’t want them to overhear. But we don’t leave the room—instead, Houghton tells me that we’ll discuss what I said in a second, and the PR guy slips away, perhaps to raise the alarms.

This all happens in front of the sweetheart codes, so Houghton gives his spiel about the dirty letters—the ones that are not on display. “Soldiers are 19-year-old boys,” he says, “so they’re basically telling their girlfriends what they’re going to do to them when they get back from the war. You don’t want some rando in Washington reading that.” He’s talking about the postal censors, but for a moment, I feel chagrined—I, too, am a rando from Washington who came here to read someone’s mail.

When Houghton is done, my mention of “illegal domestic spying” is still hanging rudely in the air. But he can’t address it without the press officer present, and somehow he still hasn’t reappeared. “Where’s Jim? We lost Jim,” Houghton mutters to himself. “Jim!” he calls plaintively down the hall. To cut the tension, my husband asks if people in the intelligence community struggle to date, and Houghton says the secrecy’s tough. After seven or so minutes, Jim emerges from a back hallway and joins us in a gaggle near the door.

“So I’m going to jump in and earn my pay and save Vince,” he says. “Your question earlier—that’s kind of outside what the museum can talk about. So if you have any specific questions about that, or even general ones, you can submit them to media relations, and we’ll be happy to answer them if we can.” Honestly, I’m shook—It’s been a decade since Edward Snowden. You’d think they’d have developed a better statement by now.

But I’m not trying to be Glenn Greenwald—I’m here on a date. And for that, the NSA museum excels. Secrets are sexy, and the gift shop is stocked; we got an NSA-branded ice scraper for the car. Before I leave, I throw out a Valentine-themed question: Is the human heart a puzzle, a code that people can break? For this one, the PR guy is ready: “It is, and you should come to the National Cryptologic Museum to unlock the mystery,” he says. On this, I’ll admit that he’s right.