Until a few days ago, it apparently would’ve been perfectly legal to have a big ol’ baboon or an 11-foot king cobra as your roommate in Loudoun County.

Only recently did the locality ban the private ownership of such creatures, along with a number of other exotic and venomous animals. Here’s what’s now off-limits: non-human primates, such as baboons and marmosets; non-native species, such as koalas and kangaroos; any venomous creatures, such as scorpions and king cobra snakes; wolf hybrids; and more. (Some common exotic pets, such as hedgehogs and guinea pigs, are still legal.)

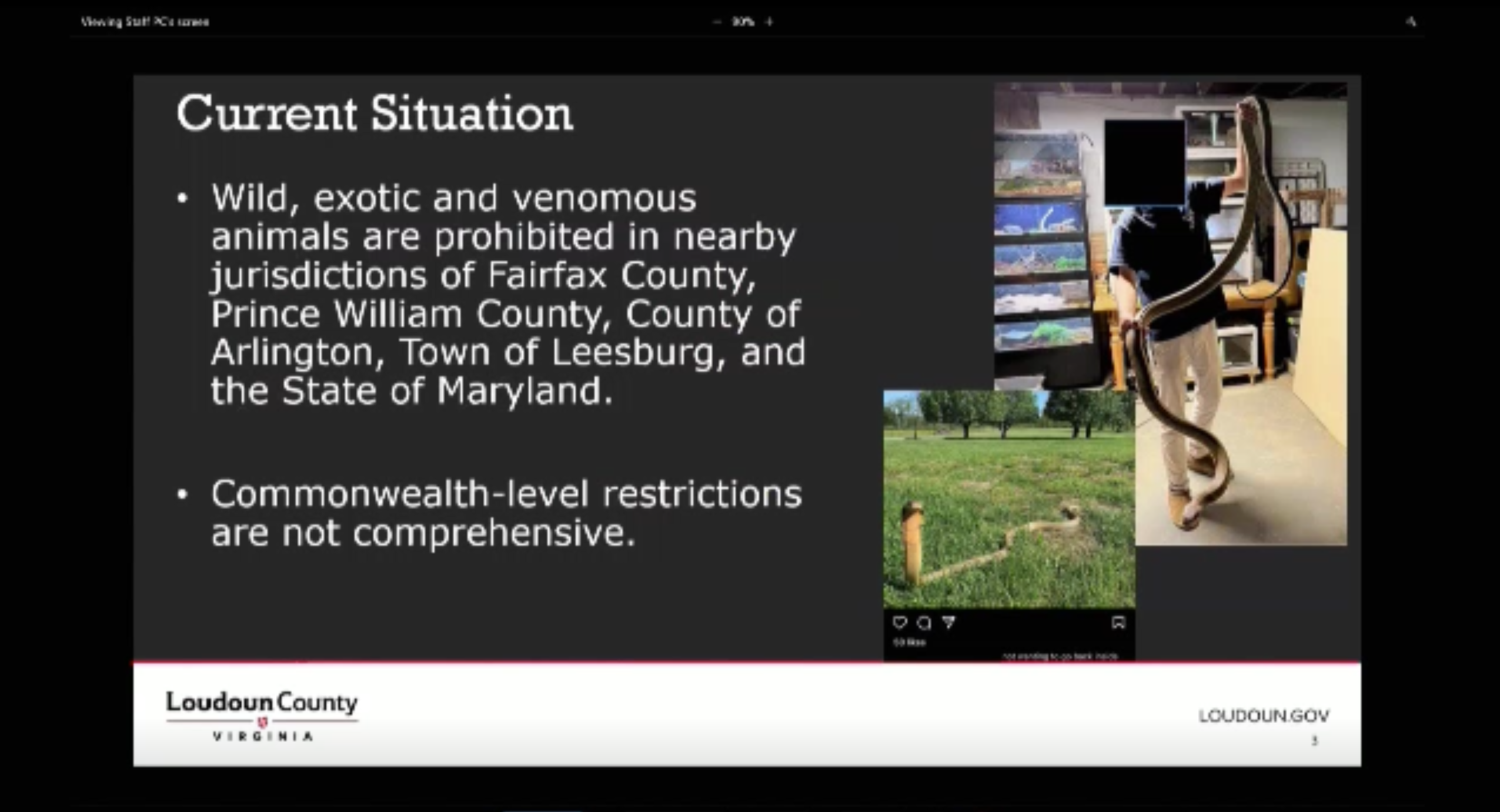

Since neighboring jurisdictions, including Fairfax, Arlington and the state of Maryland, have already banned such creatures, Loudoun County was sort of the final frontier for exotic animal owners in the area.

“If someone were to have one of these animals for private ownership, the place they would likely want to be living would be Loudoun County,” said director of animal services Nina Stively at a Board of Supervisors public hearing on Feb. 15. In other words, if you were a perfectly sane person who wanted, say, an emotional-support kangaroo, Loudoun would’ve been your best bet. No longer.

But why ban them now? Why didn’t they prevent the ownership of these beautiful wild beasts long ago?

“I don’t think there’s a specific reason as to the length of time that it took,” said Loudon’s chief of humane law enforcement, Chris Brosan. “Obviously, anytime you put a new ordinance in place, it’s a time-consuming situation. It just seemed appropriate to push forward with this type of ordinance given the situations that we’ve seen recently.”

“Situation” is a kind word. Just last year, one Virginia man was allowing his pet alligator to freely roam his property. At one point, the gator had gone missing for an entire week until someone spotted it at a Virginia vineyard. When officers arrived at the owner’s home, they found two other alligators, a caiman, and seven venomous snakes, including gaboon vipers and an 11-foot king cobra.

At the time, the Department of Wildlife Resources had license to remove the alligators and caiman from the home (Virginia state law already prohibits private ownership of them), but the lack of local regulations meant the venomous snakes could stay behind with the owner, who, apparently, granted similar freedoms to his king cobra.

During one board of supervisors meeting, Stively shared an Instagram post from the owner, which showed the tropical creature slithering around a Loudoun field. “If you could read the caption, it says, ‘He doesn’t want to go back inside,’ so this was a snake essentially roaming,” said Stively, who noted that snakes are talented escape artists and can quickly slip into plumbing and ventilation systems. She added that the nearest anti-venom would have to come from the Smithsonian National Zoo, which has a limited supply, or from the Kentucky Reptile Zoo.

This apparently wasn’t an isolated incident. According to the report, officers have responded to residents owning scorpions, foxes, coatimundi, and wolf hybrids. Brosan says he’s personally had 26 encounters with privately owned non-native venomous snakes.

That’s also an issue because such creatures can carry harmful zoonotic diseases—armadillos carry leprosy, for example—and pose serious risks to local ecosystems (as many, many headlines out of Florida have shown). Plus, exotic pets put first responders at risk, said Stively. They may respond to a call not knowing that, say, a loose baboon is inside the home.

People who already call such creatures family won’t have to part with them just yet. A grandfather clause gives residents until May 8 to register their exotic pets, which would allow them to keep an animal throughout the rest of its natural lifespan—so long as the county knows about it. All non-registered pets will be taken away.

The county also hopes that grandfathering the animals will prevent current owners from doubling down on secrecy. Otherwise, there’s really no way of knowing how many exotic animals currently call Loudoun home, says Brosan.

He said that as of yesterday afternoon, no one has stepped forward to register an exotic or venomous animal, though he added that it’s only been a few days. For reference, according to a board of supervisors report, when Arlington County passed a similar ordinance in 2015, people came forward with a wide variety of species, including vervet monkeys and armadillos, some of which were housed close to other residences.

Asked what might compel people to own such animals, Brosan was pretty empathetic: “I think most people are fascinated with wildlife and a lot of people have great relationships with animals, so they kind of merge the two and take up an exotic pet,” he said. “But people can get in over their heads pretty quickly. There are just some animals that should be not should not be pets.”