When my boss offered me a comped ticket to the Bruce Springsteen show, I obviously said yes. I’d heard it was pricier to get into a Bruce concert than the Peter Thiel apocalypse bunker, and while I’d only knowingly heard around seven Bruce songs in my life, I was open to the opportunity to hear a few dozen more.

Prior to seeing Bruce, my impression of him was vague—a creature of the New Jersey boardwalks who clawed his way to fame through some mystical combination of huge muscles, loose hips, and earnest songs about cars. To me, Bruce was the embodiment of the kind of dumbstruck male sexuality most often seen in high school cafeterias, who also—bizarrely—happened to be best friends with Barack Obama. I wasn’t interested. Then, in 2016, Bruce’s memoir earned rhapsodic reviews, suggesting that he was a serious person with real things to say about masculinity and American decline. Really? The shirtless guy washing his Camaro in a headband? But I wanted to form an opinion for myself.

Outside Capital One Arena on Monday night, the scene is wild: the cops have shut down an entire city block so that the flock of dads may safely graze en route to Bruce. There are dads in bracelets, dads in vests, dads with hair almost-but-not-quite too long for an office job. Dads in denim jackets, red flannel shirts, and button-downs. There are some older women in peasant tops, walking alongside dads in shirts from The River Tour. One dad, standing in front of me in line, is talking to another dad about ticket prices. “I don’t tell my wife shit,” he says. “If it’s expensive? Nah.”

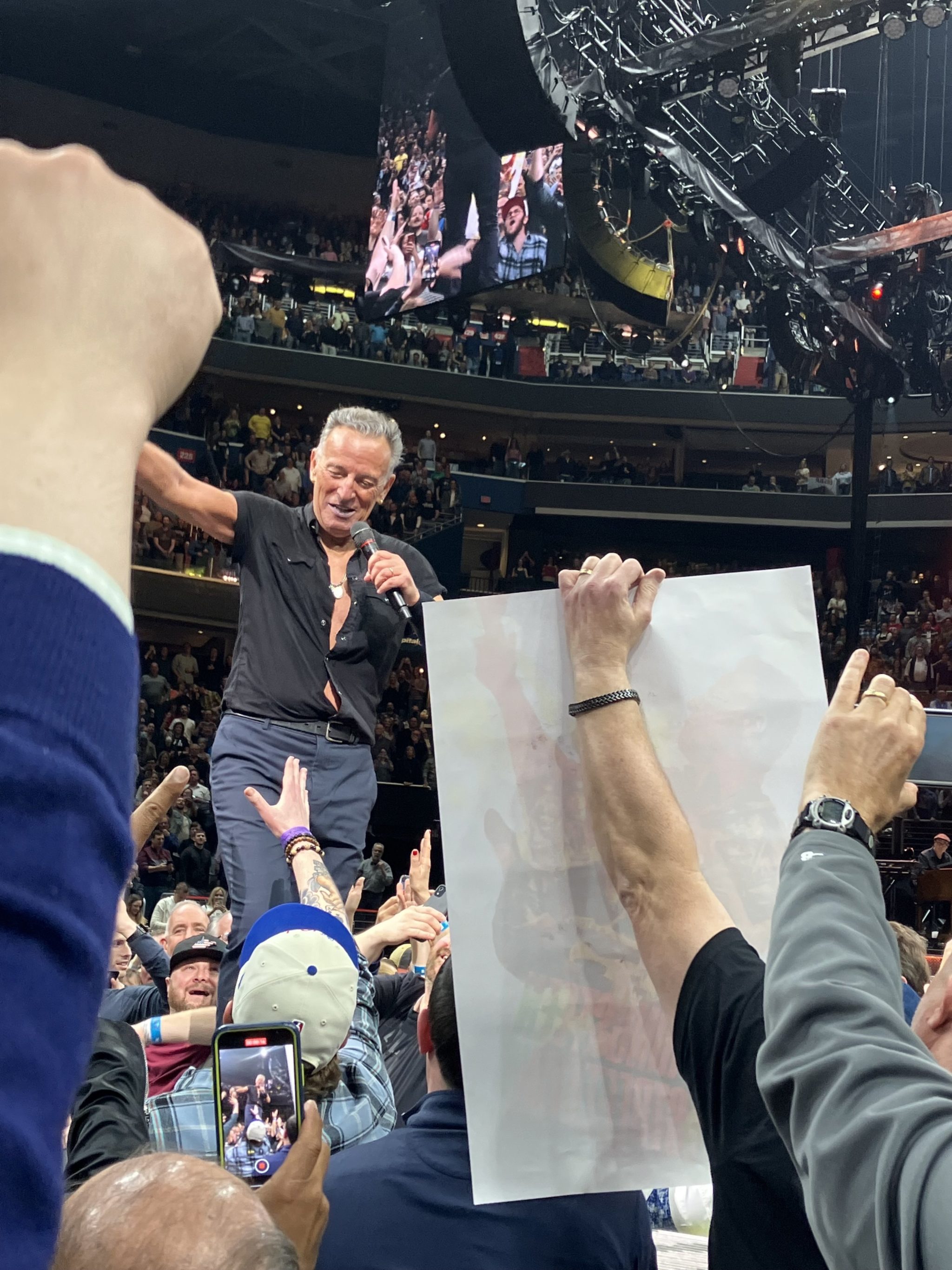

And oh, how expensive it is! When I’m escorted to my floor seat, just two rows back from the pit, the guy behind me claims he paid eight grand so that he and his wife could sit this close. “It’s kind of a bucket list thing,” he says. Sheepishly, I confess that I’m here for work and can only name a handful of Bruce songs, and he shakes his head at me, bewildered by my good fortune. In front of me, two dads who just met are chatting about iconic Bruce shows of the ’80s, then one holds out his hand and introduces himself as Greg. “Me, too!” the other one shouts. “I’m also Greg.” They vigorously shake.

Bruce Springsteen and the current incarnation of his E Street Band are supposed to appear at 7:30, and it’s 7:34 when one of the Gregs begins grousing. “If it’s going to be a three-hour set, it might as well start on time.” I blanch. A three-hour set? But a dad behind me (earring and button-down, first saw Bruce in 1978) reassures me that, now that the Boss is 73, it might be more like two-and-a-half. Just then, the lights flicker and the crowd begins booing. “It sounds like they’re booing, but actually they’re ‘Brucing’,” he explains.

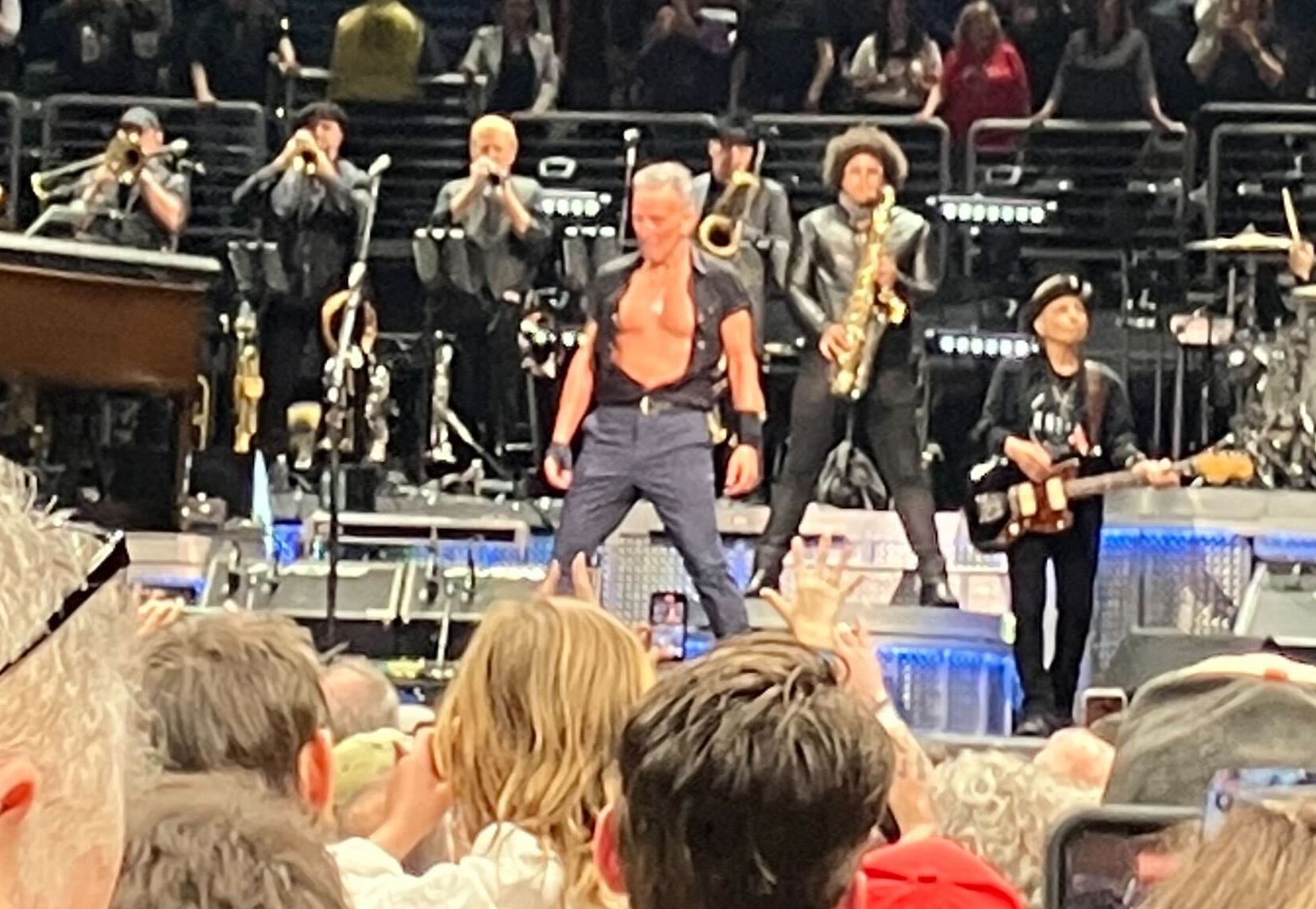

Dutifully, the Gregs insert their earplugs, and one-by-one, members of the E Street Band bound onstage. I swear, there must be 30 of them—including a man dressed as a pirate: leather pants and a billowing black-and-red iridescent shirt with a matching headscarf. Finally, from the bowels of the stadium, Bruce himself appears. He’s clad tight pants, boots, and a black button-down, sleeves rolled high. And there they are: The Muscles, the ruins of which can still clearly be seen.

Bruce counts off the band, and immediately I am bludgeoned by sound, legitimately concerned that I might go deaf. The keyboard is jangling into my brain, a sax screams a repetitive motif, and oh, God—the harmonica! It shrieks across the stadium like a fight between the biggest cats in the world. I wonder briefly if the beats rumbling through my chest might trip an arrhythmia. If decibels were raindrops, I’d have already drowned.

To be clear, it’s not that the E Street Band is bad—it’s just literally so loud that I can’t hear anything. The lyrics are gibberish, and any instrument playing below the range of “shrill” blends into formless, overcooked sound. Later, I will call my Boomer dad who cheerfully tells me that floor seats are for suckers and I should have sat by the soundboard in the back. But for what it’s worth, the crowd doesn’t mind—from their screaming, I can catch snippets of lyrics, such as “got down on my knees,” “all night,” “swamps of Jersey,” and “want to explode.”

One thing I can hear, loud and clear, are the Bruce guitar solos. Those rip. 10/10.

Given the acoustic morass, I spend the first hour mostly watching. Bruce is howling into the mic, his face tomato-red under pulsing veins, sweat pooling on his upper lip. At one point, he kneels down and screams “wheee” into the mic—perfectly on pitch—then blazes the harmonica. He’s like a toddler in a kiddie pool on the first hot day of summer, buoyant and unselfconscious. It’s totally endearing to watch.

Not that you asked, but Bruce is still hot. Straight up. A fine looking man. Is he 73? Yeah. Does he look 73? Well, yeah. But he has the face of someone with fewer than two grandchildren—maybe three, max, if you get up close.

For a long moment, I admire Bruce’s hair on the Jumbotron, which is supple and wavy, thick like tropical grass. His hips are still shockingly loose, and during one song, he does a winsome arm gesture like an angel flapping his wings. Watching this wiry man in his tight black clothes swivel around the stage and growl into the mic, it hits me like a tidal wave: This is a rock star—a bona-fide, 20th century rock star. I’ve never actually seen one before. Wow.

When I told my boss I knew seven Bruce Springsteen songs, that was just an estimate. Actually, I can only name five—“Dancing in the Dark,” “Born to Run,” “Born in the USA,” “I’m on Fire,” and “Atlantic City”—none of which Bruce plays for the first two hours of his show.

But I’ll tell you what he does play: About an hour and a half in, the band quiets and spooky piano notes chime across the arena, a sound I can’t quite place. Then suddenly I can—it’s “Because the Night,” which I had not realized Bruce wrote for Patti Smith. Finally, it doesn’t matter that I can’t hear anything, because I actually know the song.

During “Because the Night,” the beats running through my body no longer feel like a cardiac threat, and the dads are transfigured into compatriots, sharers in the night, which definitely belongs to us. During the song’s shredding portion, I see a little girl illuminated in the red stage lights, held high in her dad’s arms. For a moment, they laugh into each other’s faces. It’s then that I briefly understand what everyone else must be feeling, the actual fans.

“Because the Night” is my peak Bruce moment, the only song I even remotely recognize until the 45 minute encore, when he plays slightly worn-out versions of “Born to Run” and “Dancing in the Dark.” But after “Because the Night,” I am looser. I’m grinning. I don’t even mind that someone spilled my $14 jumbo beer.

For the rest of the night, I clap enthusiastically as the band clowns around onstage. Bruce is doing some kind of sexy sideways hip popping thing, and I love it. He shakes his butt to the crowd while watching the trumpet play a wiggly little solo at the back of the stage, then does some melodramatic pseudo-conducting of the brass. At one point, the horn section hops up front and follows Bruce around in something resembling a conga line, bouncing up and down as they walk. Bruce looks slightly sheepish, but he still can’t contain his joy.

During the encore, things onstage come a little unglued. Between songs, Bruce starts making monkey noises into the mic while the pirate guy plays with his ears from behind. Then Bruce unbuttons his shirt down to the belt, popping out his bulbous pecs and flexing them as the crowd shrieks. Thousands of iPhones are raised to capture these historic, grandfatherly mounds, then Bruce tucks them back in without bothering to re-button. He is giving the people what we want.

Chest peeking out, Bruce soldiers on, and the sounds emanating from the stage appear to have freed the dads of their burdens. For the final songs, they’re “Brucing” like mad and miming drum fills while shouting something I cannot for the life of me make out. Watching them, it’s like I’m remembering the future; should I be so lucky, the bands of my youth may someday do stadium tours that let me feel 16 again for three ecstatic hours on a Monday night after work. The dad next to me is grasping at the air in front of him while shouting lines like “strap your hands ‘cross my engines.” In a few minutes time, while streaming from the arena, I will hear another dad remark that this night was so magical that he might skip his son’s wedding to go see Bruce again. That feeling seems worth eight grand.

But first, the E Street Band is excused and Bruce plays his final song solo—acoustic, stripped down, with every note audible. It’s great. Then he holds his harmonica aloft, shouts “the E Street Band loves you,” and walks offstage into the dark.