About Goodbye RFK

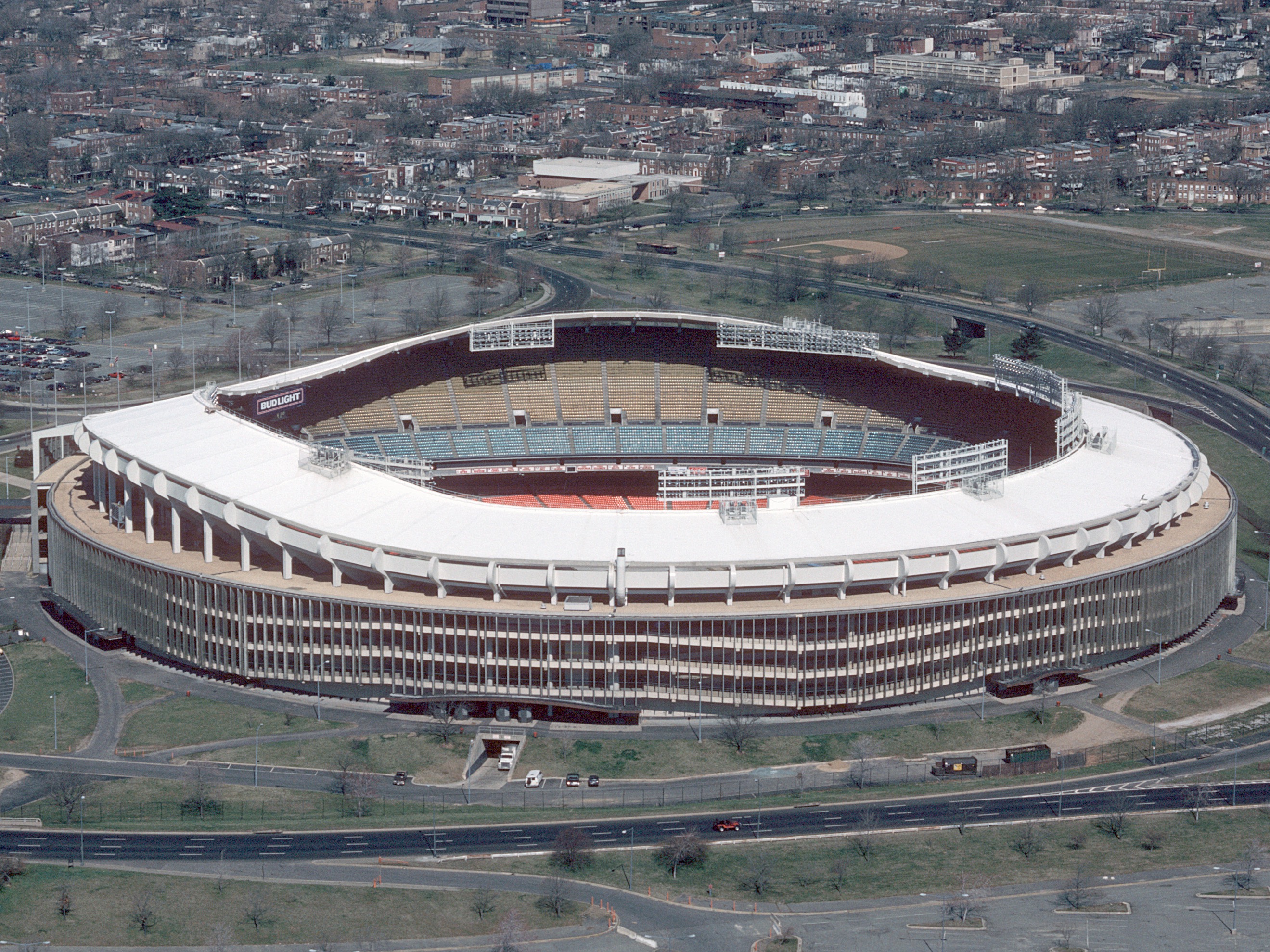

For 62 years, RFK was where Washingtonians came together. We celebrate and remember its history and legacy.

During its long history, RFK wasn’t just a venue for sports and concerts. It was also an instrument for social justice.

Though Washington’s football team represented a city with a majority-Black population, in the early 1960s it was the only National Football League franchise without a single Black player on its roster. This steadfast refusal to integrate was driven by the club’s famously racist owner, George Preston Marshall, who once said he would add Black players to the lineup only “when the Harlem Globetrotters start signing whites.”

Such naked bigotry outraged local activists and the press. Washington Post sportswriter Shirley Povich used his column to blast Marshall, describing the team’s colors as “burgundy, gold and Caucasian.” But opposition to the team’s integration wasn’t limited to the owner’s box. When civil-rights advocates held demonstrations near the stadium, according to the Post, they were met by pro-segregation counter-protesters from the American Nazi movement.

However, integration advocates had a powerful ally. In March 1961, President John F. Kennedy launched an initiative to root out discrimination in hiring federal workers—and his Interior Secretary, Stewart Udall, saw an opportunity to address the bigotry at the hometown football team. Doing so, Udall believed, would allow Kennedy to tackle a high-profile case of racial injustice while increasing his appeal with key voters, according to Thomas G. Smith, the author of Showdown: JFK and the Integration of the Washington Redskins. “[Udall] sold that to Kennedy as a shrewd political move,” Smith explains. “He said this would win us friends in the North and [would] win us friends among the Black community.”

After securing Kennedy’s approval, Udall sprang into action. The Interior Secretary recognized that because the federal government owned the land on which the team’s much-anticipated new venue—DC Stadium, later renamed RFK—was being built, it had leverage over Marshall. Udall told the owner that if he didn’t begin integrating his team, Uncle Sam wouldn’t let them play in the new building.

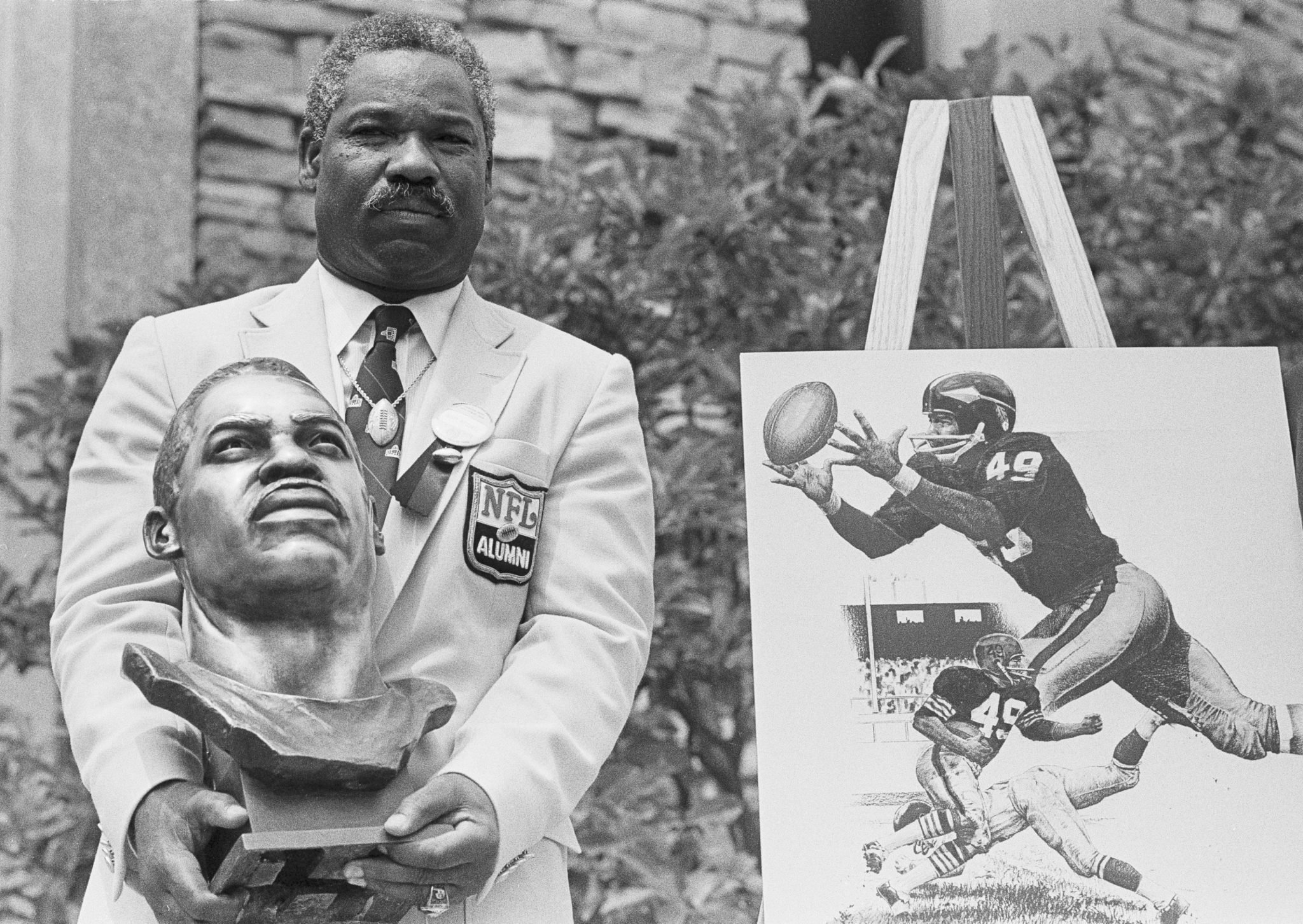

Initially, Marshall remained defiant, insisting to a reporter that Udall had “absolutely no jurisdiction over the stadium.” But the owner eventually caved. Udall permitted Washington to play in the new stadium with an all-white team in 1961, and the franchise agreed to add Black players the following season. After a dismal 1–12–1 campaign, Washington traded for Cleveland Browns halfback Bobby Mitchell.

Alongside three other Black players, Mitchell broke Washington’s color line in 1962. He became the team’s first Black star—and as he helped turn around their fortunes with electric offensive play that earned him an eventual place in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, everyone in DC wanted to claim credit for his arrival. As Mitchell once told a Post reporter, “It’s funny, I was in [Congressman] Adam Clayton Powell’s office one day that first year I played for the Redskins and he said, ‘I’m the reason you’re here playing in Washington.’ I’d just been to the White House and John Kennedy and his brother are telling me they’re the reason I’m here. The Interior Secretary, Stewart Udall, would tell me the same thing.”

Smith, by contrast, sees the integration of the football club as a total team effort, a historic feat that wouldn’t have been possible without public pressure from Washington’s Black community and reporters, the courage of players like Mitchell, and the federal muscle made firm by RFK Stadium.

This article appears in the April 2023 issue of Washingtonian.

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)