On January 30, Tiffany Cianci found out her baby had no heartbeat. Cianci and her husband, Ryan, had been trying for a few years to have their fourth child and had learned she was pregnant less than two months earlier.

The pregnancy had been troubled throughout January, with Cianci experiencing on-and-off contractions since slipping in the shower at Christmastime. Should she miscarry, her doctor told her in early January, there were several ways to end the pregnancy. After delivering the news about the baby’s heartbeat, Cianci’s doctor said she could take up to a week to choose between surgical intervention or continuing with the labor her body already had begun. A Catholic with strong views on abortion, Cianci wanted labor. “Whatever would happen would happen naturally,” she says. “That’s the advice I had from my clergy.”

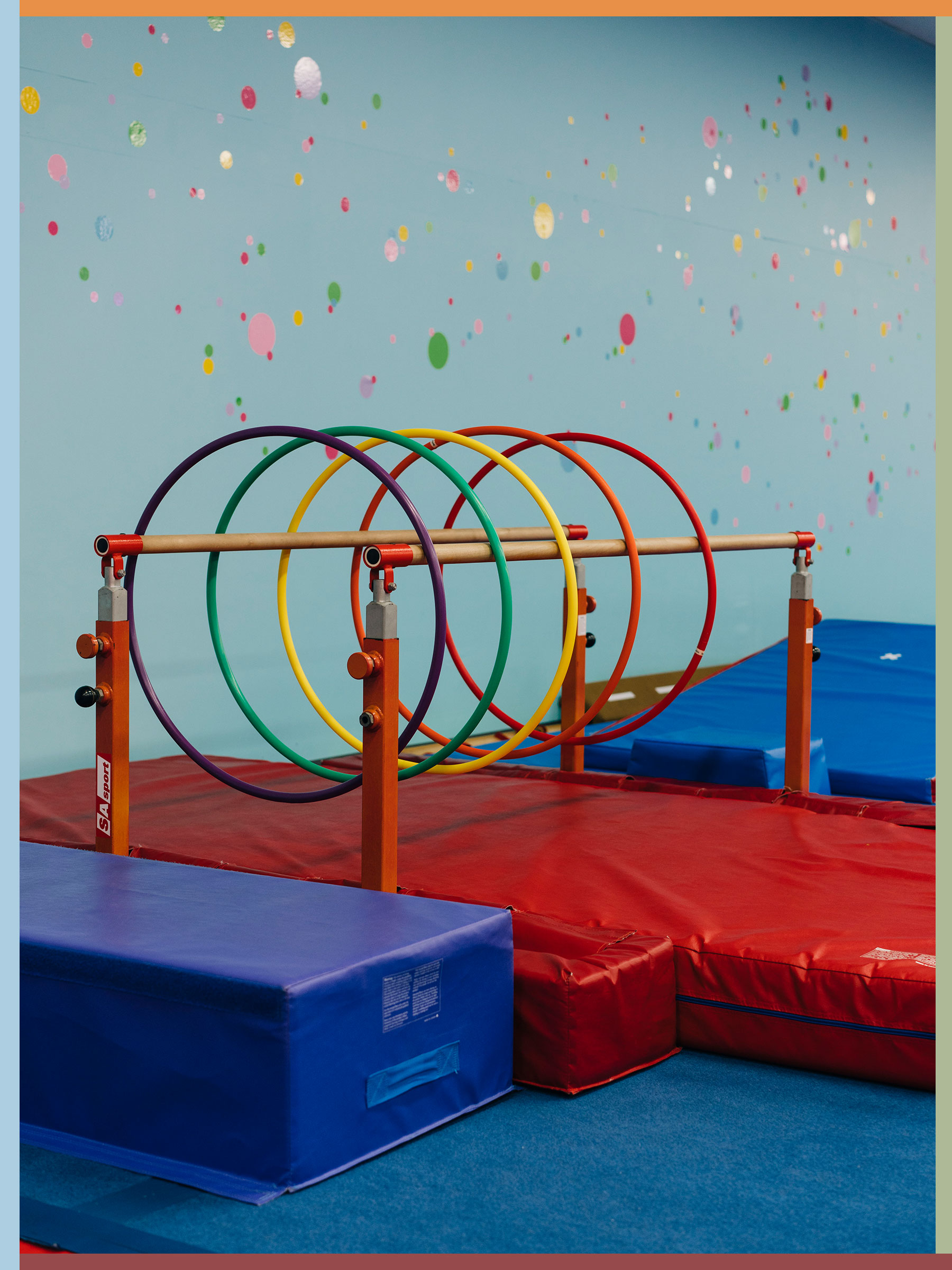

Cianci’s doctor wasn’t the only person who needed to know about her decision. There were also lawyers. Until the previous spring, Cianci had been the owner of a gymnastics facility for young children in Frederick, called the Little Gym, which was part of a national franchise chain. In 2021, the chain was purchased by Unleashed Brands, a private-equity-backed company. After Cianci pushed back against Unleashed’s efforts to change her franchise agreement, the company terminated her franchise.

Since then, Cianci had become embroiled in a bruising legal battle with Unleashed—and the fight was about to become more punishing. The company wanted her to testify in private arbitration in Arizona, home to the Little Gym’s corporate headquarters, on February 2 and 3. Through her attorney, Peter Lagarias, Cianci asked for a delay and sent along supporting medical documents, including a note from a nurse midwife in her doctor’s office.

While Cianci hadn’t made a final decision on her medical options, the note said she would be “scheduled for a surgical procedure within the next week.” For Unleashed, that wasn’t satisfactory. That evening, Laura Sixkiller, a partner at DLA Piper in Phoenix who was representing the company, emailed the arbitrator in the case, Pat Irvine. “We do not want to be unreasonable,” Sixkiller wrote, “but it is imperative that we move forward with the deposition this week and we believe the updated doctor’s note allows for that.” Irvine disagreed. “I read the note from the doctor as sufficient to justify postponing the deposition until at the earliest one week after her procedure,” he wrote.

Unsatisfied, Unleashed then asked to see “all available dates for the procedure so that we can be assured that they have selected the earliest date feasible.” Cianci had known about the possibility of surgery since January 5, Sixkiller wrote, so “if it can be scheduled this week, it should be. Given she had her deposition scheduled, she should have a clear calendar.”

Irvine again disagreed. At home, Cianci wrestled with her decision. Throughout the month, even as she’d sent Unleashed’s lawyers every medical chart and doctor’s note, they had peppered her with discovery requests. She posted a video to a private Facebook group for owners of franchises, telling her story while sobbing. “I think it’s safe to say the price was too great,” she said.

The next morning, Unleashed sent another email demanding bank records. Lagarias told Cianci that the company intended to seek sanctions if she didn’t comply—possibly resulting in fines. The Ciancis already had maxed out their credit cards and emptied their retirement accounts to cover more than $350,000 in legal fees. Feeling overwhelmed and wanting to keep things moving, Tiffany decided to get the surgery. “I caved,” she says.

Before my first meeting with Cianci, I asked how I’d recognize her. “You can’t miss me,” she said, and she was right. The 41-year-old has blazing red hair, wears chunky eyeglasses, and favors bright prints. She talks quickly—“I’m very functional with my ADHD,” she says, “it helps me”—and when we couldn’t get together in person, she returned my calls within seconds.

Cianci’s new business is called Teeter Tots Music n Motion and is located in Frederick’s Francis Scott Key Mall. Most days, she says, she comes home around 8 pm and spends 30 to 60 minutes making dinner and checking her kids’ homework. She then heads upstairs to her office, where she works on her case until 3 or 4 in the morning. While reporting this story, I spoke with Cianci dozens of times over a seven-month span; every time I asked her how she was doing, she replied with some variation of I’m in hell.

“I was looking to not keep missing everything in my kids’ life.”

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. When the Ciancis purchased a Little Gym franchise in 2017, they were searching for better work/life balance. Tiffany had spent decades in the hospitality industry, first in Las Vegas, where she’d grown up, then around Washington and Baltimore. After years of study and overseas travel, she earned the title of master sommelier in sake. But after having her third child, she yearned for less travel and more time at home.

“I’d been killing myself traveling back and forth to Japan,” Cianci says. “I was looking to not keep missing everything in my kids’ life. I wanted something local that I could do.”

The Little Gym in Frederick fit the bill. When Cianci’s oldest daughter underwent two kidney reimplantation surgeries, it was one of the few places she was able to safely have fun. Cianci’s other children also took classes at the facility, and after its owner retired, the Ciancis decided to take the plunge into franchise ownership.

In doing so, Cianci was following a well-worn entrepreneurial path: Pay an upfront fee and a cut of your profits to a corporate mother ship, agree to a set of standards covering everything from employee attire to the color of wall paint, and in return enjoy business support and the use of a nationally known and trusted brand name.

At the time, Cianci felt it was a fair deal. She enjoyed drawing on her previous study of music and dance, loved working with children, and appreciated the then–family feel of the larger company, which has nearly 400 locations and offers physical instruction to children from four months to 12 years old. Every year, the Little Gym organized an annual business conference for franchisees like Cianci—a gathering where kids were welcome, and just like classes at the gym, sessions opened with the company’s signature “Hello Song”: Oh, you come to gym for fun / And we’ll get you on the run / How do you do, how do you do, how do you do?

During their first three years of ownership, the Ciancis invested a big chunk of their savings, about $200,000, into replacing old equipment and building a local following. By early 2020, they were on track to become profitable—and even when the pandemic hit, Cianci was able to keep her business afloat, joining forces with 19 other franchise owners to offer virtual dance and gymnastics classes that were popular with parents struggling to juggle childcare and working from home. The Little Gym’s national office helped out by allowing franchisees to defer payments until they could reopen. When Maryland finally allowed Cianci to reopen in the summer of 2021, she says, “I was so excited.”

That same week, The Little Gym organized a conference call for franchisees. Also on the line were representatives of Unleashed, a Texas-based company that has 1,300 franchise owners across six brands and is the brainchild of founder and CEO Michael Browning Jr.

Browning started Unleashed in 2021. Building on the success of Urban Air, a trampoline-park chain Browning had previously created, the new company began buying other chains offering children’s activities such as e-sports and martial arts. The business strategy was simple: Own kid-centric brands, cross-market and cross-sell, and make money across entire childhoods, with today’s Little Gym toddlers becoming tomorrow’s teenage black belts.

Last December, Unleashed sold a majority stake to the California-based private-equity firm Seidler Equity Partners for an undisclosed price that Axios reported could be around $1 billion. The company plans to keep expanding—but its rapid growth has come with controversy. According to court documents and the trade publication Franchise Times, more than 100 franchise owners have sued Unleashed. They accuse the company of changing the terms of their contracts, misleading them about the expense and difficulty of ownership, and imposing requirements and fees that make their businesses unprofitable.

In court documents, Unleashed has denied those allegations. In other articles and public statements, the company has said that the lawsuits represent a small percentage of its franchise owners and that its changes have benefited owners by boosting revenues. That’s similar to the position taken by the International Franchise Association, an industry trade group, which says most owners are content. “Tiffany’s story is one story of 800,000 stories in the business,” says IFA’s CEO, Matthew Haller.

Washingtonian spoke with former and current Unleashed franchise owners who said the lawsuits reflected their experiences with the company, but none would go on the record.

During the initial call with Little Gym franchisees, Cianci says, Unleashed was introduced as a marketing partner—but soon enough she realized the company was taking over. At first, Cianci felt hopeful. Unleashed promised to invest in technological upgrades that the pandemic-battered franchisees desperately wanted, such as new point-of-sale systems, a refreshed website, and an app.

Cianci’s optimism wilted, however, as the company made a series of moves that she found perplexing. At the Little Gym’s annual convention, she says, organizers cut a beloved longtime employee’s mic during the “Hello Song”—then announced that the song and other rituals would no longer be a part of the event.

According to court filings, Unleashed would call Little Gym owners at work at odd hours and during slow times, like spring break, to see when phones were answered. The company says it called “during normal operating hours.” This was used to justify creating a national call center that would handle customer service for individual locations—something franchisees potentially would have to pay extra for.

In November 2021, Unleashed asked Cianci and other owners to sign ACH agreements that would allow Unleashed to automatically deduct franchise fees and royalty payments from owners’ bank accounts. Cianci discovered that a group of Urban Air franchise owners had sued Unleashed in 2020, claiming that the company used ACH agreements to siphon fees from their accounts that hadn’t been codified in its franchise agreements.

Cianci consulted her personal lawyer and decided not to sign Unleashed’s agreement, worrying that its wording could open the door to something similar. Having previously made payments via an online service, she began to mail checks to the Little Gym’s corporate office—which she says she understood to be allowed under the terms of the ten-year franchise agreement she had signed in 2017. The company says Cianci was “literally the only Franchisee in the system who refused to sign.”

According to Ben L’Italien, a franchise consultant who teaches at Georgetown University, it’s not unusual for private-equity-backed companies to try extracting more cash from franchise owners when they acquire chains, particularly when they finance those acquisitions through debt. But Cianci says there wasn’t a lot of extra revenue to be squeezed from a business that divides its customers into groups like “jazzy bugs” and “giggle worms.”

“They bought us for the money,” she says of Unleashed, “and [owners] didn’t buy [franchises] for the money.”

Unleashed encouraged Little Gym owners to sell more birthday parties, even though many owners thought the financial return wasn’t worth the effort. As the company acquired more brands, it ordered cuts to Little Gym programs that were similar to those of its new corporate siblings, such as martial-arts classes and building with Lego bricks. The company says these programs were “highly underutilized by the customers.”

During an April 2022 call with franchisees, some of whom were balking at Unleashed’s changes, Browning issued what sounded like a soft ultimatum. “From this day forward, we need unity,” he said. “And if we find that we have people either trying to create disunity or not supporting the vision, we will help you exit.”

Late that month, Unleashed sent Cianci a notice of default for not signing the ACH agreement. Shortly thereafter, the company sent notices to other owners who had not signed the call-center agreement, warning that they also would be found in default. Meanwhile, Cianci was helping organize her fellow owners. A group of them formed the Happy Handstands Franchise Association in May and elected Cianci as its president. Cianci says 93 percent of Little Gym owners ultimately joined. On May 19, the association sent a cease-and-desist letter to Unleashed, asking that the company rescind the ACH agreements and call center.

The next day, Unleashed terminated Cianci’s franchise.

Unleashed said it was terminating Cianci’s franchise for being habitually late in paying fees and royalties. The company says she was between 90 and 151 days late on “at least six separate occasions.” Cianci says she had been paying on time—but Unleashed hadn’t been cashing her checks. To comply with a non-compete clause in her franchise agreement, she would have to “de-identify” her Frederick gym by removing all Little Gym “trade dress”—company logos, signs, leotards.

Unleashed said it was terminating Cianci’s franchise for being habitually late in paying fees and royalties. The company says she was between 90 and 151 days late on “at least six separate occasions.” Cianci says she had been paying on time—but Unleashed hadn’t been cashing her checks. To comply with a non-compete clause in her franchise agreement, she would have to “de-identify” her Frederick gym by removing all Little Gym “trade dress”—company logos, signs, leotards.

“There’s no such thing as a trade secret in gymnastics. Everyone knows how to teach a cartwheel and a forward roll.”

Cianci’s franchise agreement required her to try to resolve disputes in arbitration. She filed for an injunction, arguing that her franchise’s termination amounted to retaliation for her involvement with Happy Handstands. An arbitrator declined to move the case forward, and Unleashed says the Little Gym did not learn Cianci was leading the association until “several weeks” after her franchise was terminated.

In early June, Cianci had surgery on her broken right foot. Hobbled, she worked to revamp her business, renaming it Teeter Tots and changing the classes it offered. During this time, Unleashed made a settlement offer that would require her to accept the changes to her franchise contract—and, she says, to promise never to advocate for owners again. Unleashed says the Little Gym never asked for that. Cianci declined.

Then things got weird. According to court documents, Unleashed sent “secret shoppers”—including a private investigator—to her studio. Pretending to be parents, the shoppers tried to get Cianci’s employees to admit that their new business was exactly the same as the Little Gym’s. Their goal, Cianci says, was to show that she was drafting off her previous association with the company’s brand, thereby giving up trade secrets. “There’s no such thing as a trade secret in gymnastics,” Cianci says. “Everyone knows how to teach a cartwheel and a forward roll.”

In July, Unleashed sued Cianci in superior court in Maricopa County, Arizona, alleging that she hadn’t de-identified quickly and thoroughly enough. An Unleashed lawyer sent an email to all Little Gym owners warning them not to share information with a certain unnamed owner who had been terminated for not paying royalties and fees on time. The email also contained a screenshot of a Facebook post that the Unleashed lawyer said came from the unnamed owner, using a derogatory and misogynistic vulgarity to describe a customer. Cianci denies that the post came from her.

Meanwhile, Unleashed’s lawyers visited Mike Kelly, Cianci’s landlord. According to Cianci, they told Kelly she would no longer be able to pay her rent. (Kelly confirmed the visit to Washingtonian but wouldn’t comment on what was said; Unleashed told the New York Times that the visit was “part of a standard process to inquire as to the status of the lease.” )

Kelly declined to renew Cianci’s lease. He claimed that she owed back rent from the pandemic; she says Kelly forgave those payments and testified to that effect in arbitration. (Kelly declined to comment on Cianci’s claim, but in March, Kelly’s company sued Cianci’s company over the disputed past-due rent.) Kelly gave Cianci a few extra days to move out, and she vacated in early August—leaving behind several thousand dollars’ worth of equipment. Her previous location remains closed, and Unleashed says the Little Gym has taken possession of the space and intends to open a new location there.

Cianci set up Teeter Tots in a church basement, then moved to her current location, situated between a Macy’s and a lash-and-brow studio. The new business is specifically designed not to compete with the Little Gym: Cianci has modified her parallel bars and balance beam so they’re useless as gym equipment, and she teaches classes based on Kindermusik, a music-and-motion program that the Little Gym no longer uses. “I have 20 percent of the customers I had [with the Little Gym location],” Cianci says. “We lose money right now. I haven’t been able to focus on it, and haven’t been able to focus on growing it.”

Cianci isn’t afraid of a fight. In January, the New York Times highlighted her clash with Unleashed in an article about the problems that can arise when private-equity firms invest in franchise brands. The company responded by publishing a “debunking” on its website, annotating portions of the article with rebuttals, snarky commentary, and celebrations of its growth—all in red Comic Sans–like font.

Cianci isn’t afraid of a fight. In January, the New York Times highlighted her clash with Unleashed in an article about the problems that can arise when private-equity firms invest in franchise brands. The company responded by publishing a “debunking” on its website, annotating portions of the article with rebuttals, snarky commentary, and celebrations of its growth—all in red Comic Sans–like font.

One of those comments reads, “Were you aware Tiffany has a history of these types of articles when things don’t go her way?” The comment refers to a 2014 Baltimore Sun article about Cianci suing a previous employer, the Four Seasons hotel in Baltimore, after she was laid off as beverage director in late 2013.

In that case, court documents show, Cianci claimed managers at the hotel’s restaurants—then operated by the Mina Group—had tried to force her to serve alcohol that she claimed they’d acquired in violation of Maryland liquor laws. She also claimed that managers had harassed her as her pregnancy progressed and, after she gave birth to her daughter, asked her why she insisted on breastfeeding rather than feeding her baby formula. When she pressed for a private place to pump, Cianci said she was given an office with a huge window and had to sit under a desk to express milk.

The defendants were chastised by the judge for apparently presenting one of Cianci’s former employers with what they claimed was a valid subpoena. The hotel tried to enforce a provision that would require Cianci to move her case to arbitration, but the judge threw that out, too, because she’d signed it (under duress, she says) after making a complaint about alcohol sourcing.

The parties eventually settled. “All I can say about it is that the parties reached an amicable disposition,” Cianci says. The owners of the hotel rehired her to work in their restaurants. Cianci also says she has learned to carefully read documents that employers ask her to sign.

In September 2022, Cianci filed a motion accusing Unleashed and its lawyers of “unclean hands”—a legal term for acting unethically in relation to the subject of a lawsuit. Unleashed immediately moved to have its own lawsuit dismissed. The case moved back to private arbitration, a process in which disputes are settled outside of court through an independent third party—typically an attorney or retired judge—who listens to arguments, examines evidence, and issues a legally binding judgment.

Since the early 2000s, American companies increasingly have required customers and employees to sign agreements that force them to resolve disputes in arbitration. Proponents of arbitration say it saves money and time compared with the courts, but critics contend that it replaces the public legal system with a privatized version that stacks the deck in favor of businesses.

Unlike regular court proceedings, arbitration records are private, shielding participants from scrutiny. Many procedural and evidentiary rules that exist to ensure fairness in civil litigation do not apply; instead, arbitrators are largely free to determine what evidence can be presented. A 2019 Stanford University study of 9,000 arbitration cases found that “pro-business” arbitrators—those with a pattern of awarding customers less money than their peers—were 40 percent more likely to be chosen for cases. That same year, a report from the American Association for Justice, a trial-lawyer advocacy organization, claimed that individuals in arbitration had a better chance of being struck by lightning than winning a monetary award against a large company.

In Cianci’s case, Unleashed argued that she failed to sufficiently de-identify Teeter Tots and that her new studio competes with the Little Gym—even though there are no Little Gym locations in Frederick and the closest one is in Gaithersburg, about 26 miles away. Cianci argued that her new business was substantially different from the old one, that Unleashed defamed her in its lawyer’s email, and that her franchise’s termination amounted to retaliation.

The arbitration process, Cianci says, was both frustrating and expensive. She says Irvine, the arbitrator, repeatedly refused to allow evidence she wanted to introduce. She also had to pay for his time in advance, splitting the cost with Unleashed. In May, Cianci spent two and a half weeks in Phoenix testifying; while posting on TikTok in the evenings, she said she needed to come up with nearly $25,000 to continue the case, then floated the idea of selling photos of her feet online. “I did ballet for a really long time,” she told her viewers.

@tiffanycianci #greenscreen #PrivateEquity Billionaires are destroying my #SmallBusiness and i am so so so tired. But im not giving up! Any odeas where i can sell pictures on my feet? My toes are adorable. #THISISWHYWEFIGHT #SmallBusinesses Need HELP, #legislation, and the #FTC! @gofundme @nytimes @azhousedems ♬ original sound – TiffanyCianci

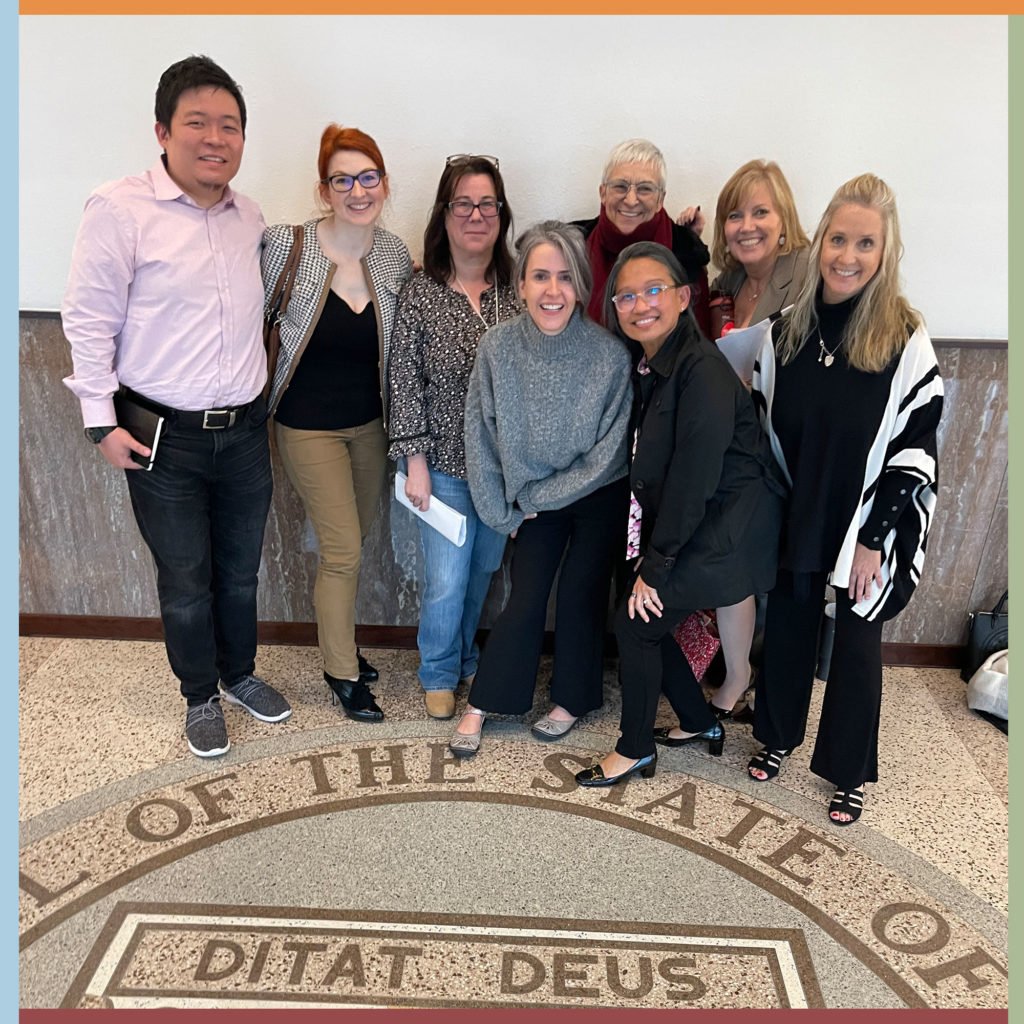

Outside of social media, Cianci has drawn attention to her case—and to some of the broader challenges facing franchise owners—by sharing her story with Franchise Times and the Dallas Morning News. Lawmakers are taking notice, too. In recent years, several states have floated legislation that would empower franchise owners; under President Biden, the National Labor Relations Board and Federal Trade Commission have shown interest in doing the same. While in Phoenix for arbitration hearings, Cianci spoke to Arizona lawmakers who were considering a bill inspired by her situation that would set stricter rules for terminating franchise owners and protect their right to form associations.

Industry lobbying efforts prevented the bill from reaching the state senate for a vote, says state representative Stacey Travers, who sponsored the bill. But Cianci made an impact. “[The lobbyists] came just to kill the bill and discredit Tiffany,” says Travers, adding that she intends to reintroduce the bill “every year” going forward.

“I’ve got to get an army to help me.” Cianci was upset—and uncharacteristically subdued—when we spoke on the phone. It was early June, and Irvine had just issued a preliminary ruling in her case. Most of it went Unleashed’s way. He found that the Little Gym had a right to enforce deadlines for Cianci’s payments even if it suspended them during the pandemic, and that whether or not the company retaliated against her for forming Happy Handstands was irrelevant.

Irvine also found that the Facebook post in the Unleashed’s lawyer’s email about Cianci defamed her. Irvine believed Cianci’s denial and said that Unleashed failed to investigate whether the post actually came from her. However, Irvine said that Cianci couldn’t show she’d been harmed by the post, so he awarded no damages. (Cianci says she couldn’t produce therapist bills to demonstrate the costs of her mental anguish over the email: “I was too busy fighting to go to a therapist.”)

The Little Gym, Irvine wrote, couldn’t show damages either, because Teeter Tots was not profitable. He found that Unleashed failed to show that Cianci had violated trade secrets, but also ruled that Teeter Tots incorporated elements of the Little Gym that could confuse customers. As such, Irvine ordered Cianci to close her business and forbade her from selling products or services to previous Little Gym customers for two years. Unleashed, he wrote, could also seek its legal costs from her.

Shortly after the ruling, Unleashed sent an email to Little Gym franchise owners about the case, stating “we won” and that Irvine’s decision “validates what we have long asserted.” A lawyer for the company told Washingtonian in an email that the “last thing [the company] ever wants to do is get into a lawsuit with a Franchisee” and that the ruling “is a win for all Franchisees and Franchisors.”

Ryan Cianci, Tiffany’s husband, says the entire battle has been wrenching for his family. He sometimes wonders if Unleashed was attempting to make an example out of them so that other owners stay in line. “For them, it’s a victory because this will get publicized,” he says. “Everyone who reads [about] it will say, ‘What won’t they do to me?’ ”

Tiffany Cianci plans to keep fighting. She hopes to appeal the ruling in court but said she needed to raise $20,000 in the next nine days to do so. She estimated that Unleashed’s legal fees were in the millions of dollars and that paying them would bankrupt her. When I asked whether she had $20,000, she said, “I don’t have $500 right now.” (The couple hope that a GoFundMe campaign might help them pay for an appeal.)

Cianci has opened other fronts in her campaign. In March, she filed an ethics complaint against Unleashed’s attorneys with the State Bar of Arizona, citing the email and the demands made during the end of her pregnancy. The association replied that it would investigate, and Unleashed “strongly” disputes Cianci’s allegations. As the FTC considers implementing more protections for franchise holders, she has been in touch with the agency’s staffers and has begun to hold informational online sessions for franchise owners who want to leave comments for the FTC and believes those sessions have led to thousands of the comments people left. “I just have to protect other people from this exact thing that happened to me,” she says.

Despite Irvine’s ruling, Cianci has no immediate plans to close Teeter Tots. A few weeks before the interim ruling, I was there when toddlers formed a line to receive hugs from “Miss Tiffany,” who had just returned from testifying in Arizona. One little boy showed her an elaborate truck that he had built from Duplo bricks. A small group of children ran in a circle, holding pool noodles and singing. All around us were brightly colored walls, foam steps, and safely rounded corners. “We’re in a padded room,” Cianci said. “But the rest of the world is not a padded room.”

This article appears in the July 2023 issue of Washingtonian.