Justin “Yaddiya” Johnson always has a lot of projects in the works—have you heard his new EP, L.A.T.E.?—and his latest is what he calls “Go-Go Alumni”: A way to show, he says, “the impact that go-go has had on many successful people’s lives from the area.” Because the city’s homegrown music still fights for respect on multiple fronts. The mainstream has never known quite what to do with it, and while DC’s political establishment has embraced go-go in recent years, it hasn’t been that long since the powers-that-be pushed the music underground, citing its proximity to violence in previous decades.

Yaddiya’s big realization was that go-go—which, he notes, “is Black culture in DC—could be a vessel for change. The Moechella events that he helped organize beginning in 2019 helped thousands of native Washingtonians assert their place in a gentrifying city. Go-go was the pulse of racial-justice protests in 2020, and Yaddiya, who started promoting shows as a teenager, has taken DC music far beyond the District line. With the Go-Go Alumni project, though, he wants to highlight how DC culture infuses many aspects of life in the city. So earlier this month, his first class of a dozen prominent people gathered in a theater at Georgetown University—where a season-long celebration of go-go is in progress—to discuss their experiences with the music, and how it shaped their lives. “This is just the start,” Yaddiya says.

Janeese Lewis George

Attorney, member of the DC Council for Ward 4

“I don’t remember a time when go-go was not a part of my life. Go-go always feels like family-reunion vibes, just love, celebration, dancing. It just invokes so much joy and pride. Pride is a huge part of go-go, too, like, proud of who we are as DC culture, proud of who we are as Black people. That’s the feeling that you get every time you’re in that space. And as soon as you hear go-go music, it just feels like home.

“I’m the one who ran for office out of the whole #Don’tMuteDC movement. Yaddi was like, Janeese, you gotta be the one. So that activism made it more than just about go-go, but how do we preserve DC culture and make sure that we have a place in its future and that our music, our culture are preserved and celebrated in a positive way.”

Lafayette Barnes

Publisher/CEO, the Washington Informer Bridge

“I grew up on Mississippi Avenue in Southeast DC, Congress Heights. And there were times in the summer where I would walk down to Oxon Run Park and Backyard Band, or some major bands that you might pay 50 bucks to see, were just out in the park performing for free. It was always a bonding moment—a place of safety, a place where I can interact with people in my community and not have to worry about what gang I was from or anything like that. I went to Wilson High School, and in those days they had these things called Blackouts, when private schools like Sidwell, Gonzaga, and Maret had go-go parties. It’s part of my fabric as a person.

“We’re about to do an edition in the Bridge about, What does modern go-go look like? It’s not really my scene anymore. And not because I don’t want it to be, it just has become a lost scene. I thank the mayor for supporting it. But when things are commissioned by the government, the fun is taken out. Now it’s sort of turned into a more commercialized, politicized thing.

“My grandfather started the Washington Informer newspaper, and my mother became the publisher once he passed. I grew up in the newspaper office. The Bridge is a monthly insert in the Washington Informer, it’s basically our millennial, gen-Z facing product. We hope the Bridge can be the bridge for people to the Informer. I’m two, three degrees of separation from anyone that we’ve ever covered.”

June Sanders

Design director of DTLR; designer of the New Balance DC992, among other DMV-centered shoes

“I think you have to touch people emotionally. And that’s what go-go is: Emotional. When I’m creating, I want to make sure that whatever I’m designing touches people emotionally, just like go-go music.

“We made this music for us. If you don’t have nothing, you always have music. Go-go is the bloodline of what makes us happy. Mainstream artists, they know about go-go music. It’s big to us, but small to everybody else. It’s no knock on anybody else. We just love what we love.”

Virginia Ali

Owner, Ben’s Chili Bowl

“For me it was all about Chuck Brown. I opened the Ben’s Chili Bowl in 1958, when I was 24 years old. When I first heard go-go, it was from Chuck Brown, who used to hang out by the Chili Bowl quite a bit. It was music that you just couldn’t sit still. Every time we were in any place where he was playing, if you were seated, you had to get up and have some kind of movement, because the music just moved you. As a matter of fact, once he did a commercial for the lottery, and he did it right in front of the Chili Bowl. Everybody thought that commercial, we paid for it. [Laughs.] So it was beneficial to the lottery, to Ben’s, and to Chuck. I see the people moving into my community, young educated people, and they like go-go. One of my children wrote a go-go song: ‘The real DC is go-go and Ben’s.’ Whenever we do anything, we have the go-go bands. It’s part of the culture. It originated right here.”

Dre “Dre The Mayor” Hopson

Founder, HighRes Global, home to artists like yvngxchris, BabyFxce E, Adé, Innanet James, and others

“My uncle was actually in a go-go band, he was a backup drummer for Rare Essence. So as long as I can remember, the music was around.

“Go-go shaped my approach to life, because I always felt like our culture was different than anywhere else. I always felt like we stood out wherever we went because our music and fashion and go-go culture just didn’t blend with anything else. I love that. I love being an individual and our accent, our slang, all of that was centered around go-go music. I always wanted to export our culture to the world. I think the person who had the best run with making go-go and mainstream mesh was Wale. There’s been moments where mainstream culture has taken to what we do. But I think it performs best when we do it original.”

Avanté Davis

Photographer, artist, owner of the clothing brand GoonMilk

“I have been listening to go-go my whole life. My whole family’s been in the go-go scene. I had an uncle who was in [the band] Suttle Thoughts. It’s the lifeline around here, you know? My first go-go was at the Mad Chef [in Capitol Heights, Maryland], that turned into the Le Pearl. I literally used to walk there every single show. Go-go is the heartbeat of the city.

“I went to Morgan State. Nobody [there] liked go-go. But the bands would travel up to do homecoming shows. You would know who’s from here just by seeing them at the go-go parties. I had a girlfriend from Delaware, I wouldn’t say she didn’t like it, but she didn’t understand it until she went to a go-go. She was like, Oh, it’s an actual experience. When you see it, you understand it’s not just a cover of a song. You’re actually playing toward the crowd and having a call-and-response.”

Dr. Jennifer Hawkins

Foreign policy specialist

“I actually focused a lot of my work for my dissertation looking at how to use go-go music to get young people to vote. We did a whole campaign [called GoGo Vote]. We had a couple thousand kids register to vote. Just through the music.

“I’m in the foreign policy and international relations space, so I spend a lot of time now out of the country working on foreign affairs. To me, DC’s very interesting in the sense that the music we listen to is indigenous to Africa. Congas, drums, percussion: It’s a very African sound. It’s our connection to some places that most people in the city have never been. It’s that connection to our African ancestry. So when I go around the world, particularly on the continent, I hear go-go through congas, through dance. It’s very familiar to me. So it’s a fascinating connection to me of being like home away from home. I’m working on women and girls’ issues, but when I’m seeing women dance, when I’m seeing the percussionists play, it’s like being at home.”

Kevin “Scooty” Hallums

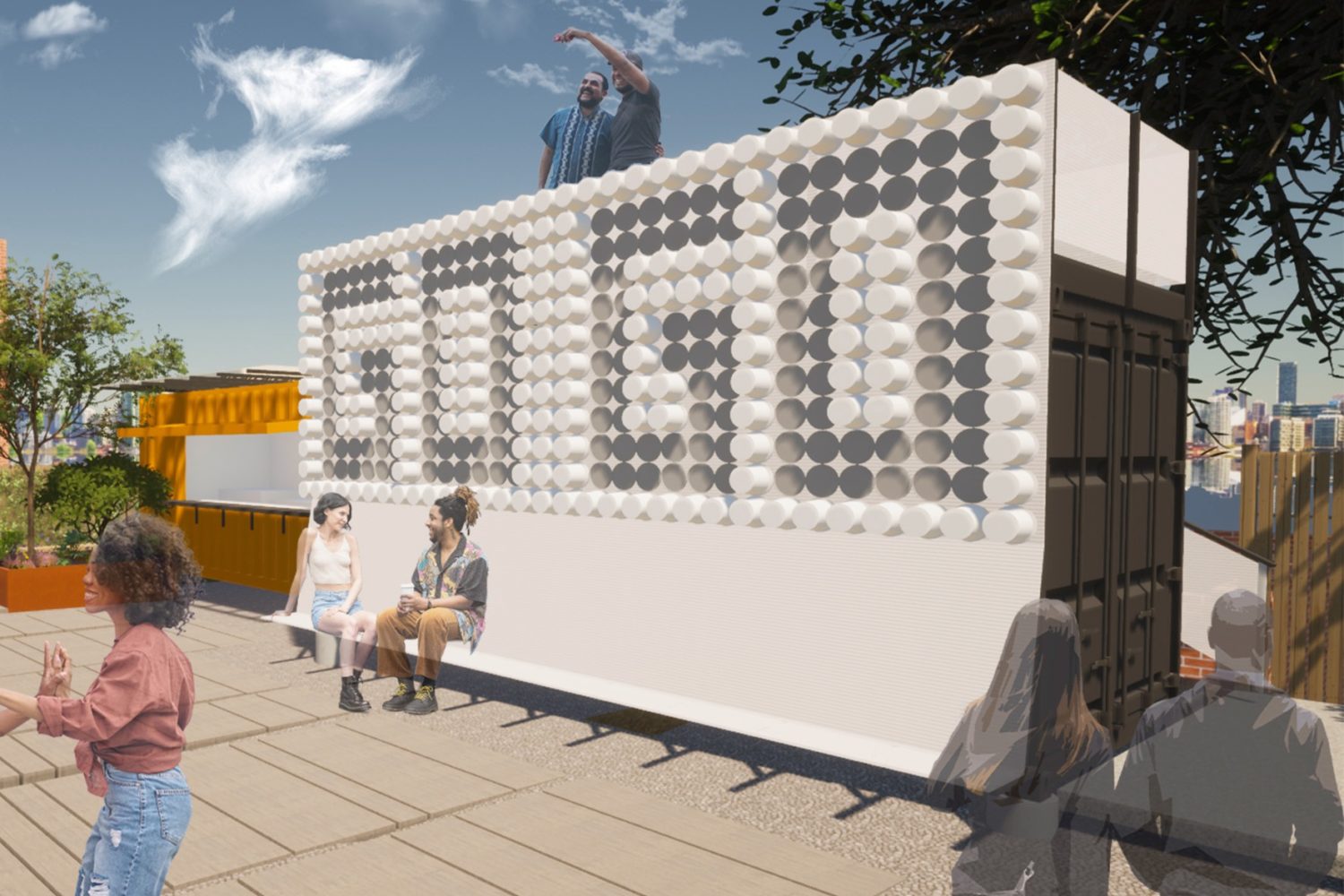

Co-owner, Sandlot DC

“I always call it the heartbeat of the city, but it’s definitely the theme music to my life. I think a lot of times that people don’t really understand the percussion in a live music aspect because they only hear the commercial version of it, they’ve never actually been, and felt the actual energy of being inside an actual go-go. You have different generations, you know, there’s a difference between a Rare Essence and a Backyard Band. And there’s a difference between a Backyard and a New Impressionz. I think that every band is trying to carve out their own lane.”

Sheldon “YOSHELLZ” Silver

Dancer; choreographer; co-founder, Beat Ya Feet Academy; Prince of Beat Ya Feet and Captain of the Washington Commanders’ Command Force

“I’m now teaching around the world. I use certain go-go songs in my classes. They have their own like, slums and projects in like Brazil and other countries. So they feel the authenticity of it. DC is so authentic, you can’t put a limit on what we can create. Go-go started one way—pocket beats, Chuck Brown and all that—but as a younger generation got involved, we put our own style and flavor in it. I’m open for it all.”

Rodney “Red” Grant

Humanitarian; philanthropist; entertainer; candidate for DC Council (at-large)

“In class, somebody would be the drummer, hitting on a desk, somebody might be the rototoms with their pencils. I’d be the fake horn. [Mimics a trumpet sound.] It’s a sound that only you can find, probably, in DC, but it’s used everywhere. We went crazy when we heard it in Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing. We couldn’t believe that a band from our city was actually in a real movie. I think when people recognize when you take that culture away, no matter who moves into the city and who says they don’t want to hear it, it’s detrimental to the whole city when you take it away. The people who move to the city, we welcome them, and they have to welcome the situation. It’s almost like going to New Orleans and telling them don’t play any brass band music. When people tell us your music sounds like some trash—I mean, this trash has been here for a while. It’s good. Trust us. It’s trash that we love. What’s the saying? Some people’s trash is another man’s treasure. It’s our treasure. Go-go’s our treasure.”

Kelsye Adams

Executive director, Long Live GoGo; organizing director, DC Vote

“My first experience with go-go was at a community event called Paradise Day. I had to be all of like 8 or 9 years old. I’ve literally never felt that feeling again—it was a first high on the music. I was elated for the whole week, I just kept telling everybody, “You gotta go see the go-go bands live! They’ll say your name!”

“I got Yaddi as the founder of Long Live GoGo, and he’s already done all the things. But as the executive director, for me to push different agendas and on the platform of us intersecting with politics. How do we use go-go to represent the 700,000-plus disenfranchised voices in Congress? Congress, keep your hands off DC! This is DC’s voice. The music needs to be a lot more respected, like when you get on Apple Music or Spotify it’s not a genre of music. DC’s voice is not heard on this music genre? It’s also not heard in the federal government. I think that that’s freaking insane. So we have so much more work to do.”

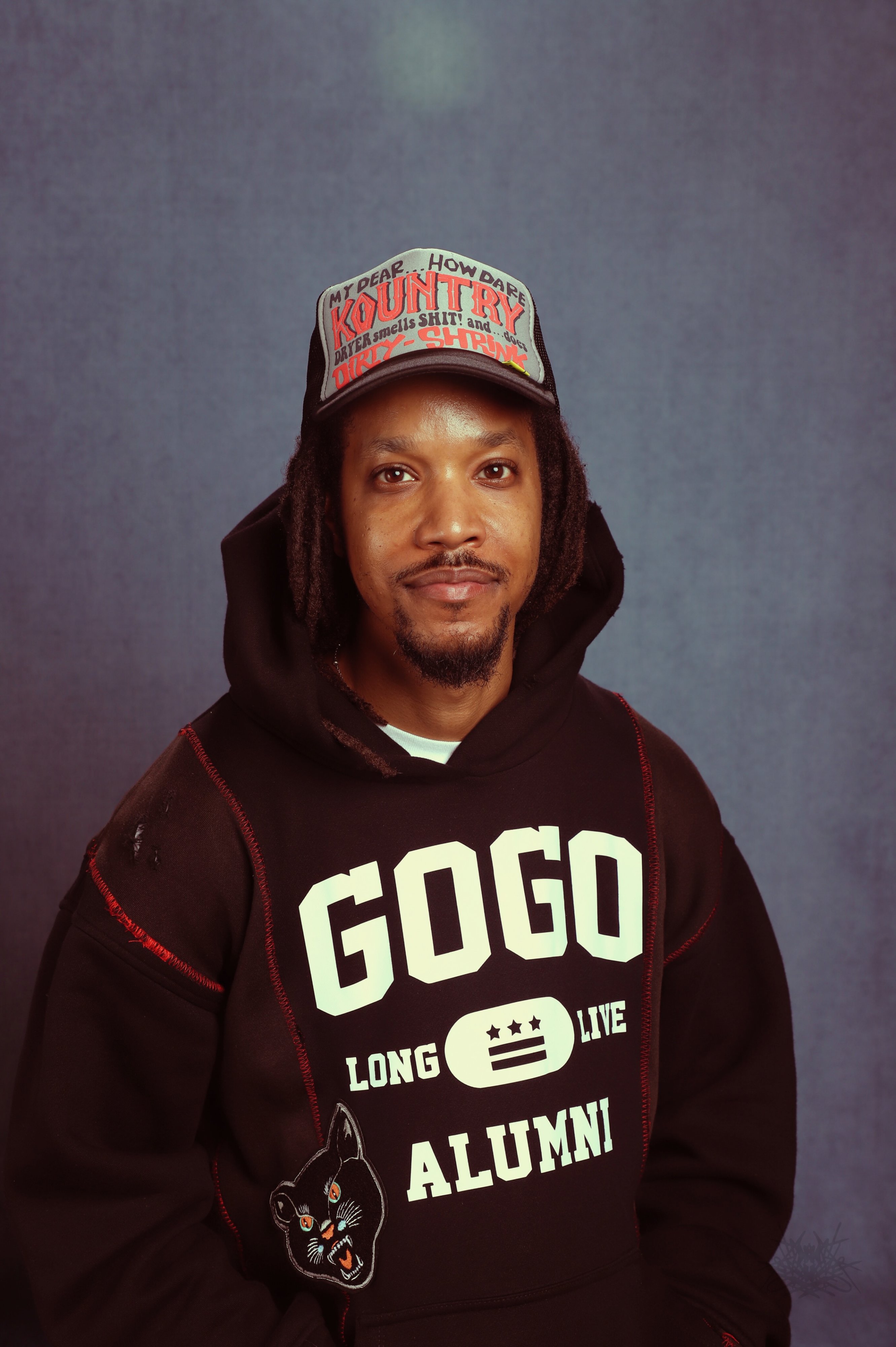

Justin “Yaddiya” Johnson

Musician; advocate; producer of Moechella; founder of Long Live GoGo

“I didn’t go to my first go-go till I was in my teenage years. I would go with friends, we’d go to the Mad Chef, the Brandywine Firehouse. It just seemed way over my head–not that I couldn’t understand the music, it was just the whole environment. It just felt overwhelming. A lot of these band members, you know, it’s their cousins in the crowd. You know, so whatever connection they got, you know, so it’s like these guys are around your neighborhood. And then you know, you go see them become a star on the weekend.

“You meet so many different people in the go-go from already so many different places, it’s like going to the damn community center. I became part of the Recording Academy because of go-go. Kennedy Center, because of go-go. I’ve gotten international notoriety because of go-go. When I meet people and hear Moechella has inspired them and impacted their lives, that means so that means a lot to me—that something that come from my heart really changed somebody’s life, or provided them an opportunity to inspire them to do better or inspire them to take action.

“If you ain’t got upper class and middle class mingling with the lower class or whatever class you want to say, it ain’t a go-go to me, man. You’ve got to bring everybody together. It’s the glue. It’s the glue of DC.”