Contents

Deb Gottesman

Cofounder and codirector, Theatre Lab; Director, Life Stories Program

After founding the Theatre Lab—now the largest independent acting school in Washington—with her friend and codirector, Buzz Mauro, in 1992, Deb Gottesman noticed something curious. While many of her students aspired to careers onstage, others weren’t there to be actors at all. Some were lawyers who wanted eloquence in the courtroom, others office workers who wanted more creativity in their life.

“That’s when we started thinking, ‘If this stuff is so powerful, why are we limiting it to people who have the means to seek it out?’ ” says Gottesman. So around 2000, she began offering workshops to communities that could benefit from what theater had to offer: self-confidence and the chance to be heard. This included seniors in assisted living, incarcerated youth, wounded veterans, and others with rich stories to tell.

It’s part of the Theatre Lab’s Life Stories program, which helps people transform their experiences into dramatic works of art. “It’s been the driving force in what we do,” says Gottesman. Since the program’s founding, more than 4,000 people have participated, including those recovering from addiction and homelessness, mothers who have lost children to gun violence, and military families who have lost a loved one to suicide. It’s become so successful that Gottesman has begun a Life Stories Institute, which trains others to lead similar workshops.

“What I love about this work is that we start to see we are not just victims of circumstance, but we are also creators and can use our experiences to speak to other people,” says Gottesman. “When we see our stories reflected back in the eyes of the people who are watching it, accepting it, and holding it gently, it’s really powerful to realize we’re not alone in many of the things we thought we were alone in.”

It’s not the only way the nonprofit has made theater more accessible. In addition to other community programs, the Theatre Lab awards more than $150,000 in scholarships each year to its students, many of whom have gone on to impressive careers on Broadway and in Hollywood.

The secret to the organization’s success? “The understanding that theater is about community,” says Gottesman. “It is the perfect vehicle for celebrating every person who walks through our doors.”

Back to Top

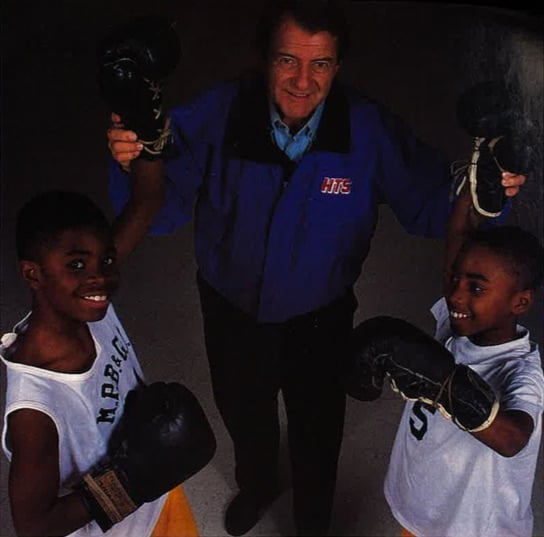

Michael Locksley

Head football coach, University of Maryland

Growing up in DC in the 1970s and ’80s, Michael Locksley learned grit and perseverance. When his parents’ marriage broke up, he lived in housing projects and relatives’ homes. His mother worked multiple jobs to keep the children fed, and he watched people he knew get killed or sent to jail. “I just saw it as ‘You know what? You’ve got to keep grinding,’ ” Locksley says. “Those struggles made me who I am today.”

Determination in the face of adversity has been at the heart of Locksley’s five-year run as head football coach of the University of Maryland, where, during the 2021 and 2022 seasons, the Terps won back-to-back bowl games for the first time in almost two decades. It has also inspired his efforts in the community.

In 2020, after witnessing firsthand the shortage of opportunities that minorities face when attempting to climb the coaching ranks, Locksley launched the National Coalition of Minority Football Coaches, a nonprofit committed to providing talented coaches of color with the skills, connections, and exposure they need to advance. In just three years, the organization has built a heavy-hitting board of directors—including Alabama head coach Nick Saban—and helped minority coaches secure marquee jobs, including Notre Dame head coach Marcus Freeman and the University of Virginia’s Tony Elliott.

“My job isn’t to make people hire minorities,” Locksley says. “My job is to make sure hiring officials know we have qualified individuals capable of running football programs at the highest level.”

Meanwhile, through a personal tragedy, Locksley has become an advocate for mental-health awareness. Over the course of his early twenties, Locksley’s son, Meiko, became increasingly unstable. Doctors diagnosed him with schizoaffective disorder, and in 2017 he was murdered by a still-unidentified gunman.

Locksley keeps two full-time mental-health professionals on staff for his players, and one game each season is dedicated to raising awareness about mental health. “It’s okay for a big, strong football player to say, ‘Hey, I’m not in a good space mentally,’ ” he says.

At the same time, Locksley in 2021 joined the board of directors of an organization near and dear to his heart: the Boys & Girls Clubs of Greater Washington. As a child, he’d found a safe afterschool haven at a Boys & Girls Club in DC. “That club saved my life,” he says.

Locksley’s service on the board, he explains, is a way to “pay back some of the people and some of the resources that helped make me who I am today.”

Back to Top

Mirah Horowitz

CEO and founder, Lucky Dog Animal Rescue

Mirah Horowitz didn’t know many people when she moved to DC as a young lawyer. So she adopted a black Lab, Sparky. Soon after, “it occurred to me that someone had fostered Sparky and that’s how I was able to find him,” she says. “I thought, ‘I could do that. I could foster and give someone else what I was lucky to receive.’ ”

Things snowballed from there. After volunteering at a local shelter, she and a few other volunteers created their own rescue organization. Four years after adopting Sparky, Horowitz founded Lucky Dog Animal Rescue in 2009.

For Horowitz, who at the time worked at the Justice Department, the rescue was a passion project. “I never envisioned it as a career,” she says. For nearly ten years, she juggled being executive director of Lucky Dog with working full-time as an executive search consultant for other nonprofits at Russell Reynolds Associates. It wasn’t until 2019 that Horowitz quit her desk job to make animal welfare her main focus. “At that point,” she says, “it was clear this was a calling.”

Since 2009, Lucky Dog has found homes for more than 27,000 animals at high risk of euthanasia—a feat Horowitz attributes to her volunteer force of 2,000 people. At any given time, more than 100 rescue animals are with local Lucky Dog foster families. “Because we don’t have a brick-and-mortar in the area, all our animals are touched by foster homes and volunteers,” says Horowitz.

While Lucky Dog’s animals come from all over—including local shelters as well as disaster-affected areas far away—most are from under-resourced places in the rural South, where many shelters face staggeringly high euthanasia rates. To help lower those numbers, Lucky Dog recently opened a rescue campus in South Carolina to provide veterinary care and temporary housing to at-risk animals awaiting transport to the Washington region.

“More animals are entering shelters than are leaving the shelter alive,” says Horowitz, who spends much of her time fundraising nearly $3 million each year and forging partnerships with other animal-welfare leaders. Still, her favorite part of the job is when she can sneak away to rescue events: “That’s when you see all the hard work pay off. You get to see the animal come off the transport van, and it’s like they’re taking their first step to freedom.”

Back to Top

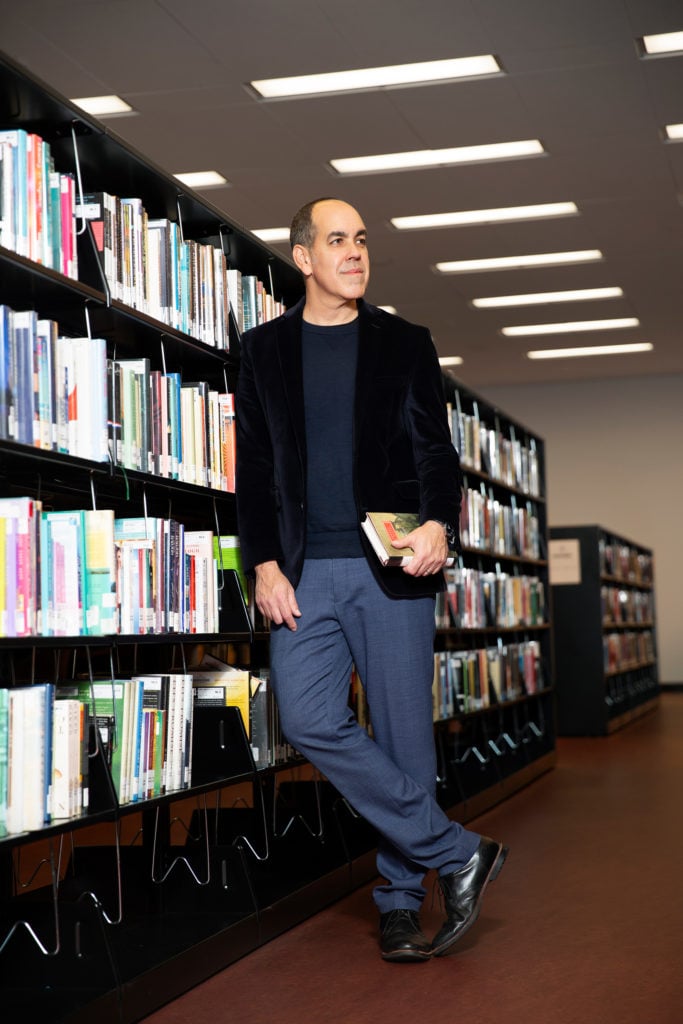

Richard Reyes-Gavilan

Executive director, DC Public Library

For Richard Reyes-Gavilan, libraries are more than places to borrow a book—they’re “engines of civic activity.”

Not that there’s anything wrong with traditional, book-centric libraries. “But as an organization funded by the government, we would not be able to justify our existence if [that’s all we did],” he says. “We have to provide solutions to civic problems, under the large umbrella of information literacy.”

For a glimpse of how large that umbrella is, take a look at some of the DC Public Library’s free services: American Sign Language courses; computer-literacy classes for adults; places to vote (and register to vote); access to news publications; and reservable sewing machines, recording studios, and 3D printers. Together, these services constitute “the library of the future,” says Reyes-Gavilan. “It’s embracing that notion that we are civic learning spaces.”

This vision for what a library can be is what appealed to DCPL’s board of trustees when it appointed him executive director in 2014. What lured Reyes-Gavilan—a native New Yorker and previously chief librarian of the Brooklyn Public Library—to DC was the opportunity to become “a leader in what public libraries can look like,” he says. “I knew I wouldn’t have to fight for funding as much as I did in New York. I could worry more about how to use the funding.”

Just what has he done with some of that funding? He’s helped open a branch for inmates in the city jail. He’s helped oversee the implementation of a “books from birth” program, mailing a free book monthly to participants from birth through age five. He’s fostered ambitious art exhibits and library programs. And he’s implemented an equity-focused master plan, Next Libris, that’s working to distribute library services fairly throughout the city. Currently, DCPL’s smallest branches are in largely low-income communities, but he and his team are working on addressing those service gaps. For example, they’re currently planning a bigger, full-service library in Congress Heights.

“What I try to do every day is sell people on the wonder of this institution,” says Reyes-Gavilan, who manages an annual budget of more than $75 million and has overseen the renewal of eight branches, in-cluding the $211 million renovation of downtown’s Martin Luther King Jr. Library. The work is never done for Reyes-Gavilan, who is already thinking of his 2030 plan for the MLK library. “We need to continue to evolve,” he says. “Residents’ needs evolve so quickly, so the job’s never really finished.”

Back to Top

Alan Meltzer

CEO, NFP/Meltzer Group

Alan Meltzer arrived in DC in 1969 on a wrestling scholarship to American University. Between studies, the working-class kid from Massachusetts held several jobs to make money. When the captain of the wrestling team told him a bar in Tenleytown needed a dishwasher for the night, Meltzer took the gig.

He would work at that bar, Mr. Henry’s, for years, dropping out of college to buy the joint with two classmates in 1972. One day, a friend asked if the bar was making a profit. It was. The friend suggested he give a bit to charity. “As I did better, I got more generous,” Meltzer says.

Did he ever. He left the bar business and in 1982 started the Meltzer Group, an insurance agency that grew to more than 300 employees. Meltzer and his wife, Amy, have given millions to AU, including $10 million to build a new athletic facility that will be named for them.

They also give to the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation and Children’s National hospital in honor of their son Mark, who has type 1 diabetes. They started giving money to MedStar after Alan had a stroke in 2018; he credits the doctors and nurses with his complete recovery. They also donate to Jewish organizations, including the United Jewish Federation and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

“The more money I gave away, the more money I made,” Meltzer says. “I’m not religious, but God looked out upon me. We almost never say no to anybody.”

He says his charity extends to his employees: “I try to treat the people who work with me, who have made me very successful, very well.”

Although Meltzer, 72, sold his company in 2016, he’s still working there. “I don’t want anyone to think I’m a saint. I’m not. I’m just a hardworking guy who likes to give back. How many houses can you have?”

One thing Meltzer did not have: a diploma. In 2019, he went back to AU to finish his bachelor’s degree. “I didn’t graduate until 2021. They made me work my butt off for it. I took five classes, including algebra. At 70, taking algebra is not easy.”

Meltzer has never been one to take it easy. He does seem to take it all with a sense of humor, evidenced by his philosophy on philanthropy: “Give until it hurts, then give a little more and you’ll feel better.”

Back to Top

Nicole Lynn Lewis

Founder and CEO, Generation Hope

Nicole Lynn Lewis was in her senior year of high school, with several college acceptances in hand, when she got the news: She was pregnant. “It was devastating,” says Lewis. “I knew I wanted to go to college, and then, more than ever, it was important for me to get a degree because I was going to have a little one.” But it felt impossible. No college seemed prepared to accommodate a young mother.

So she took a year off, during which she experienced periods of homelessness while navigating a difficult relationship with her child’s father. Determined to make college work, she reopened her applications and started school at William & Mary about three months after her daughter was born. “Having to get to class every day, even when you have a sick baby—it was incredibly hard. It was a 24-hour act of survival.”

Despite the odds—nationally, fewer than 2 percent of teen mothers obtain a bachelor’s degree by age 30—she graduated in 2003. It was “the spark that lit the fire for Generation Hope,” she says. “I felt this overwhelming desire to make sure it wasn’t as hard for other young parents.”

Since Generation Hope’s founding in 2010, its mission has been to help student parents succeed. The nonprofit provides a variety of support, including financial help and mentors. “Each student is matched with someone who, if you have a teething baby at 2 am and a midterm the next day, can say, ‘Let’s figure out how we can get you through this.’ ” So far, it has helped more than 450 student parents, both men and women, work toward degrees. What’s more, roughly 30 percent didn’t stop at a bachelor’s—they went on to graduate school.

Still, many of the barriers that have historically kept student parents out of college—the cost of both childcare and higher education—have only risen. It’s why Generation Hope also has an advocacy arm that works with organizations across the country to fight for student parents, who account for roughly 20 percent of undergraduates nationwide. As Lewis puts it, “It’s about making sure that the system across the country is set up for parents and students of any age to be successful.”

Back to Top

Darius Baxter

President, CEO, and cofounder, GOODProjects

Despite losing his father to gun violence at age nine and experiencing periods of poverty as a young boy in DC, what Darius Baxter largely remembers from his childhood isn’t bitterness—it’s love. “It was dramatic at times, for sure, but I always felt the love,” says Baxter. “My mother, who was a public-school teacher, surrounded us with love and instilled in us the importance of education.”

Because of her and the discipline gained through football, Baxter earned a scholarship to Georgetown University. It was there, in a shared townhouse during his senior year, that he and two friends, who’d also grown up in low-income communities in the area, brainstormed ways they could return the love and opportunities they’d received. They founded GOODProjects, a nonprofit that works to eradicate poverty one community at a time.

Right now, that community—or “GOODZone” as they call it—is in Southwest DC, where Baxter and his team have set a lofty goal: to elevate the incomes of 500 families in the District’s largest public housing project to $80,000 a year—far above the starting average of $14,700. “We want to create a case study for what place-based support looks like,” says Baxter.

As a “place-based” nonprofit, GOODProjects tailors its services to the multifaceted needs of a community rather than focusing on one symptom or cause of poverty. Because, as Baxter says, if you pour help into one issue in a resident’s life, they “still got to go to the same school that’s [messed] up or the same grocery store that’s not providing quality food or the same community with broken windows and people laid out on the street.”

Because of its holistic approach, GOODProjects’ services are vast (and often made possible by partnerships with other organizations): from a grocery-delivery program to a community health clinic to a six-week summer camp for kids to one-on-one mentoring.

“It’s about being intentional and having conversation with the community,” says Baxter, who regularly shares meals with parents and community members so he can hear their concerns.

Meals like these, he says, are among the most rewarding aspects of his work: “I find myself in this constant state of joy, because there’s no greater gift in life than to help those that are underserved. The thing I hear the most is ‘I can feel y’all love us.’ That’s been a blessing.”

Back to Top

Monty Hoffman

Founder and Chairman, Hoffman & Associates

Where some saw a wasteland, Monty Hoffman envisioned the Southwest DC waterfront as a bustling riverside hub that would one day rival San Francisco’s and Boston’s. The idea seemed a bit far-fetched at the time, but the developer was no stranger to beating the odds.

Hoffman arrived in Washington in 1984 with little in his pocket. He couch-surfed for six months until he landed an engineering gig at Donohoe Construction. One day, he and a coworker bought a townhouse in a crime-ridden neighborhood near Logan Circle to convert into six condominiums. People called them crazy, but the condos sold out in an instant. The duo quit their day jobs and founded PN Hoffman (now Hoffman & Associates), today one of the region’s largest developers. They rode the crest of the housing market, building condos all over Washington throughout the early 2000s. Then the market started to collapse and Hoffman’s partner left.

Not long after, an opportunity arose for Hoffman to join Baltimore-based Struever Bros. Eccles & Rouse for the bid to develop the Southwest DC waterfront. They won over more than a dozen competitors, but Struever Bros. ran into financial trouble and backed out.

That’s when Hoffman teamed up with commercial real-estate giant Madison Marquette. Almost a decade later, in 2017, the Wharf made its debut: apartments, condos, restaurants, hotels, shops, and music venues. The second phase was completed in 2022.

Hoffman says the biggest hurdle was changing the way people thought about the Southwest waterfront. That required what he calls “a big-bang theory,” in which he’d create a large presence with investors and tenants. It would take more than $1 billion, four acts of Congress, seven DC Council votes, and 800-plus meetings with Advisory Neighborhood Commissions and other community groups. “I had all these constituencies that I needed to bring together,” Hoffman says.

He was determined to keep neighborhood staples such as the Capitol Yacht Club and the Municipal Fish Market and bring in local shops and restaurants. “We needed something that was authentic,” he says. “Something that Washington and the whole nation could embrace.”

Hoffman estimates that nearly 8 million people have visited the Wharf over the past year alone. “It will soon no longer be a development,” Hoffman says. “People will think of it as a community and own it through their experiences.”

Back to Top

Shawn Yancy

NBC4 news anchor and founder, Giving Foundation for Women and Children

Shawn Yancy was pulling into the parking lot at Fox 5 on September 11, 2001, when American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon. It was just her second day on the job and a week since moving to DC from Pittsburgh. She and a photographer raced to the scene.

Yancy was frightened and devastated, but she remembers being moved as she covered the story. “In the days and weeks that came after, I got to meet the families that were touched by the horrific act and to witness the incredible love our community shared by coming together to support each other,” she says.

That experience inspired the young news anchor to approach every story from the viewpoint of the people affected, whether a teenager who won 50 scholarships or a family impacted by gun violence. Her reporting over the past two decades has earned multiple Emmys and a prestigious Edward R. Murrow Award.

Her work doesn’t end after the cameras stop rolling. When Yancy comes home late at night, she’s met with piles of clothes and toys in her living room, waiting to be donated to women and children in underserved communities. Fourteen years ago, she organized a clothing swap with a few girlfriends in her dining room. Whatever was left over was donated to a village in Liberia. She called it Girls’ Night Out and thought: “If we added a few more women, we could help more women.” Each year, additional people joined in, so she turned the swap into a big party whose proceeds would go to charities with similar missions to uplift women and kids.

What was once an annual gathering became a nonprofit called the Giving Foundation for Women and Children, with its own programs to provide essential items to those in need. In the past five years, the organization has donated not only clothing but thousands of hot meals, toys, and school supplies to families in the area and around the world. It also holds an annual Girls’ Night Out benefit gala with a bazaar of local shops and a DC-celebrity fashion show. The nonprofit has raised $180,000 since its inception.

“We’ve always believed that we’re stronger when we stand together,” Yancy says, “especially in helping women and children create pathways out of poverty.”

Back to Top

Tom Wilson

Forward, Washington Capitals

Tom Wilson has earned a reputation as the Capitals’ tough guy—a bone-crushing enforcer who makes opposing lineups tremble. But when he’s not body-checking opponents or burying rebounds in the back of the net, the 29-year-old forward is providing assists to neighbors in need.

“My parents raised me to be, first of all, a good person off the ice and [to] try and live with the right qualities,” Wilson says. “Obviously, on the ice I’m a bit of a different player.”

Among Wilson’s many charitable endeavors is 43’s Friends (the name comes from his jersey number), an organization that provides Capitals tickets to ailing children through Make-A-Wish Mid-Atlantic. Wilson welcomes the kids and their families into the Caps dressing room and introduces them to teammates. “This is something to try to put a smile on their face and let them be a normal kid,” Wilson says, “and just let them know we’re in their corner.”

Says Lesli Creedon, president and CEO of Make-A-Wish Mid-Atlantic: “He’s got this tough-guy, kind of bad-boy hockey-player image. But when he’s talking to these little kids, it just melts your heart. You can tell he really cares.”

43’s Friends also supports military servicemembers and their families, who are often kept apart by deployments. “This game,” Wilson says, “can be a time for the kids to come out—or when the dad or the mom gets home from overseas, [they can all] come out as a family and just have a really fun night.”

In addition, Wilson is an ambassador for Wolf Trap Animal Rescue, has traveled to local hospitals to visit with patients, has taken part in the Hockey Fights Cancer initiative, and has donated money that has benefited organizations such as DC Central Kitchen, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, and the Greater Washington Urban League.

“I’ve been part of this community since I was 19, and I’ve kind of grown up here,” he says. “I take huge pride in living in this city and being a part of this community, [so] any chance I can give back is super-important to me.”

Deb Gottesman

Cofounder and codirector, Theatre Lab; Director, Life Stories Program

After founding the Theatre Lab—now the largest independent acting school in Washington—with her friend and codirector, Buzz Mauro, in 1992, Deb Gottesman noticed something curious. While many of her students aspired to careers onstage, others weren’t there to be actors at all. Some were lawyers who wanted eloquence in the courtroom, others office workers who wanted more creativity in their life.

“That’s when we started thinking, ‘If this stuff is so powerful, why are we limiting it to people who have the means to seek it out?’ ” says Gottesman. So around 2000, she began offering workshops to communities that could benefit from what theater had to offer: self-confidence and the chance to be heard. This included seniors in assisted living, incarcerated youth, wounded veterans, and others with rich stories to tell.

It’s part of the Theatre Lab’s Life Stories program, which helps people transform their experiences into dramatic works of art. “It’s been the driving force in what we do,” says Gottesman. Since the program’s founding, more than 4,000 people have participated, including those recovering from addiction and homelessness, mothers who have lost children to gun violence, and military families who have lost a loved one to suicide. It’s become so successful that Gottesman has begun a Life Stories Institute, which trains others to lead similar workshops.

“What I love about this work is that we start to see we are not just victims of circumstance, but we are also creators and can use our experiences to speak to other people,” says Gottesman. “When we see our stories reflected back in the eyes of the people who are watching it, accepting it, and holding it gently, it’s really powerful to realize we’re not alone in many of the things we thought we were alone in.”

It’s not the only way the nonprofit has made theater more accessible. In addition to other community programs, the Theatre Lab awards more than $150,000 in scholarships each year to its students, many of whom have gone on to impressive careers on Broadway and in Hollywood.

The secret to the organization’s success? “The understanding that theater is about community,” says Gottesman. “It is the perfect vehicle for celebrating every person who walks through our doors.”

Michael Locksley

Head football coach, University of Maryland

Growing up in DC in the 1970s and ’80s, Michael Locksley learned grit and perseverance. When his parents’ marriage broke up, he lived in housing projects and relatives’ homes. His mother worked multiple jobs to keep the children fed, and he watched people he knew get killed or sent to jail. “I just saw it as ‘You know what? You’ve got to keep grinding,’ ” Locksley says. “Those struggles made me who I am today.”

Determination in the face of adversity has been at the heart of Locksley’s five-year run as head football coach of the University of Maryland, where, during the 2021 and 2022 seasons, the Terps won back-to-back bowl games for the first time in almost two decades. It has also inspired his efforts in the community.

In 2020, after witnessing firsthand the shortage of opportunities that minorities face when attempting to climb the coaching ranks, Locksley launched the National Coalition of Minority Football Coaches, a nonprofit committed to providing talented coaches of color with the skills, connections, and exposure they need to advance. In just three years, the organization has built a heavy-hitting board of directors—including Alabama head coach Nick Saban—and helped minority coaches secure marquee jobs, including Notre Dame head coach Marcus Freeman and the University of Virginia’s Tony Elliott.

“My job isn’t to make people hire minorities,” Locksley says. “My job is to make sure hiring officials know we have qualified individuals capable of running football programs at the highest level.”

Meanwhile, through a personal tragedy, Locksley has become an advocate for mental-health awareness. Over the course of his early twenties, Locksley’s son, Meiko, became increasingly unstable. Doctors diagnosed him with schizoaffective disorder, and in 2017 he was murdered by a still-unidentified gunman.

Locksley keeps two full-time mental-health professionals on staff for his players, and one game each season is dedicated to raising awareness about mental health. “It’s okay for a big, strong football player to say, ‘Hey, I’m not in a good space mentally,’ ” he says.

At the same time, Locksley in 2021 joined the board of directors of an organization near and dear to his heart: the Boys & Girls Clubs of Greater Washington. As a child, he’d found a safe afterschool haven at a Boys & Girls Club in DC. “That club saved my life,” he says.

Locksley’s service on the board, he explains, is a way to “pay back some of the people and some of the resources that helped make me who I am today.”

Mirah Horowitz

CEO and founder, Lucky Dog Animal Rescue

Mirah Horowitz didn’t know many people when she moved to DC as a young lawyer. So she adopted a black Lab, Sparky. Soon after, “it occurred to me that someone had fostered Sparky and that’s how I was able to find him,” she says. “I thought, ‘I could do that. I could foster and give someone else what I was lucky to receive.’ ”

Things snowballed from there. After volunteering at a local shelter, she and a few other volunteers created their own rescue organization. Four years after adopting Sparky, Horowitz founded Lucky Dog Animal Rescue in 2009.

For Horowitz, who at the time worked at the Justice Department, the rescue was a passion project. “I never envisioned it as a career,” she says. For nearly ten years, she juggled being executive director of Lucky Dog with working full-time as an executive search consultant for other nonprofits at Russell Reynolds Associates. It wasn’t until 2019 that Horowitz quit her desk job to make animal welfare her main focus. “At that point,” she says, “it was clear this was a calling.”

Since 2009, Lucky Dog has found homes for more than 27,000 animals at high risk of euthanasia—a feat Horowitz attributes to her volunteer force of 2,000 people. At any given time, more than 100 rescue animals are with local Lucky Dog foster families. “Because we don’t have a brick-and-mortar in the area, all our animals are touched by foster homes and volunteers,” says Horowitz.

While Lucky Dog’s animals come from all over—including local shelters as well as disaster-affected areas far away—most are from under-resourced places in the rural South, where many shelters face staggeringly high euthanasia rates. To help lower those numbers, Lucky Dog recently opened a rescue campus in South Carolina to provide veterinary care and temporary housing to at-risk animals awaiting transport to the Washington region.

“More animals are entering shelters than are leaving the shelter alive,” says Horowitz, who spends much of her time fundraising nearly $3 million each year and forging partnerships with other animal-welfare leaders. Still, her favorite part of the job is when she can sneak away to rescue events: “That’s when you see all the hard work pay off. You get to see the animal come off the transport van, and it’s like they’re taking their first step to freedom.”

Richard Reyes-Gavilan

Executive director, DC Public Library

For Richard Reyes-Gavilan, libraries are more than places to borrow a book—they’re “engines of civic activity.”

Not that there’s anything wrong with traditional, book-centric libraries. “But as an organization funded by the government, we would not be able to justify our existence if [that’s all we did],” he says. “We have to provide solutions to civic problems, under the large umbrella of information literacy.”

For a glimpse of how large that umbrella is, take a look at some of the DC Public Library’s free services: American Sign Language courses; computer-literacy classes for adults; places to vote (and register to vote); access to news publications; and reservable sewing machines, recording studios, and 3D printers. Together, these services constitute “the library of the future,” says Reyes-Gavilan. “It’s embracing that notion that we are civic learning spaces.”

This vision for what a library can be is what appealed to DCPL’s board of trustees when it appointed him executive director in 2014. What lured Reyes-Gavilan—a native New Yorker and previously chief librarian of the Brooklyn Public Library—to DC was the opportunity to become “a leader in what public libraries can look like,” he says. “I knew I wouldn’t have to fight for funding as much as I did in New York. I could worry more about how to use the funding.”

Just what has he done with some of that funding? He’s helped open a branch for inmates in the city jail. He’s helped oversee the implementation of a “books from birth” program, mailing a free book monthly to participants from birth through age five. He’s fostered ambitious art exhibits and library programs. And he’s implemented an equity-focused master plan, Next Libris, that’s working to distribute library services fairly throughout the city. Currently, DCPL’s smallest branches are in largely low-income communities, but he and his team are working on addressing those service gaps. For example, they’re currently planning a bigger, full-service library in Congress Heights.

“What I try to do every day is sell people on the wonder of this institution,” says Reyes-Gavilan, who manages an annual budget of more than $75 million and has overseen the renewal of eight branches, in-cluding the $211 million renovation of downtown’s Martin Luther King Jr. Library. The work is never done for Reyes-Gavilan, who is already thinking of his 2030 plan for the MLK library. “We need to continue to evolve,” he says. “Residents’ needs evolve so quickly, so the job’s never really finished.”

Alan Meltzer

CEO, NFP/Meltzer Group

Alan Meltzer arrived in DC in 1969 on a wrestling scholarship to American University. Between studies, the working-class kid from Massachusetts held several jobs to make money. When the captain of the wrestling team told him a bar in Tenleytown needed a dishwasher for the night, Meltzer took the gig.

He would work at that bar, Mr. Henry’s, for years, dropping out of college to buy the joint with two classmates in 1972. One day, a friend asked if the bar was making a profit. It was. The friend suggested he give a bit to charity. “As I did better, I got more generous,” Meltzer says.

Did he ever. He left the bar business and in 1982 started the Meltzer Group, an insurance agency that grew to more than 300 employees. Meltzer and his wife, Amy, have given millions to AU, including $10 million to build a new athletic facility that will be named for them.

They also give to the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation and Children’s National hospital in honor of their son Mark, who has type 1 diabetes. They started giving money to MedStar after Alan had a stroke in 2018; he credits the doctors and nurses with his complete recovery. They also donate to Jewish organizations, including the United Jewish Federation and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

“The more money I gave away, the more money I made,” Meltzer says. “I’m not religious, but God looked out upon me. We almost never say no to anybody.”

He says his charity extends to his employees: “I try to treat the people who work with me, who have made me very successful, very well.”

Although Meltzer, 72, sold his company in 2016, he’s still working there. “I don’t want anyone to think I’m a saint. I’m not. I’m just a hardworking guy who likes to give back. How many houses can you have?”

One thing Meltzer did not have: a diploma. In 2019, he went back to AU to finish his bachelor’s degree. “I didn’t graduate until 2021. They made me work my butt off for it. I took five classes, including algebra. At 70, taking algebra is not easy.”

Meltzer has never been one to take it easy. He does seem to take it all with a sense of humor, evidenced by his philosophy on philanthropy: “Give until it hurts, then give a little more and you’ll feel better.”

Nicole Lynn Lewis

Founder and CEO, Generation Hope

Nicole Lynn Lewis was in her senior year of high school, with several college acceptances in hand, when she got the news: She was pregnant. “It was devastating,” says Lewis. “I knew I wanted to go to college, and then, more than ever, it was important for me to get a degree because I was going to have a little one.” But it felt impossible. No college seemed prepared to accommodate a young mother.

So she took a year off, during which she experienced periods of homelessness while navigating a difficult relationship with her child’s father. Determined to make college work, she reopened her applications and started school at William & Mary about three months after her daughter was born. “Having to get to class every day, even when you have a sick baby—it was incredibly hard. It was a 24-hour act of survival.”

Despite the odds—nationally, fewer than 2 percent of teen mothers obtain a bachelor’s degree by age 30—she graduated in 2003. It was “the spark that lit the fire for Generation Hope,” she says. “I felt this overwhelming desire to make sure it wasn’t as hard for other young parents.”

Since Generation Hope’s founding in 2010, its mission has been to help student parents succeed. The nonprofit provides a variety of support, including financial help and mentors. “Each student is matched with someone who, if you have a teething baby at 2 am and a midterm the next day, can say, ‘Let’s figure out how we can get you through this.’ ” So far, it has helped more than 450 student parents, both men and women, work toward degrees. What’s more, roughly 30 percent didn’t stop at a bachelor’s—they went on to graduate school.

Still, many of the barriers that have historically kept student parents out of college—the cost of both childcare and higher education—have only risen. It’s why Generation Hope also has an advocacy arm that works with organizations across the country to fight for student parents, who account for roughly 20 percent of undergraduates nationwide. As Lewis puts it, “It’s about making sure that the system across the country is set up for parents and students of any age to be successful.”

Darius Baxter

President, CEO, and cofounder, GOODProjects

Despite losing his father to gun violence at age nine and experiencing periods of poverty as a young boy in DC, what Darius Baxter largely remembers from his childhood isn’t bitterness—it’s love. “It was dramatic at times, for sure, but I always felt the love,” says Baxter. “My mother, who was a public-school teacher, surrounded us with love and instilled in us the importance of education.”

Because of her and the discipline gained through football, Baxter earned a scholarship to Georgetown University. It was there, in a shared townhouse during his senior year, that he and two friends, who’d also grown up in low-income communities in the area, brainstormed ways they could return the love and opportunities they’d received. They founded GOODProjects, a nonprofit that works to eradicate poverty one community at a time.

Right now, that community—or “GOODZone” as they call it—is in Southwest DC, where Baxter and his team have set a lofty goal: to elevate the incomes of 500 families in the District’s largest public housing project to $80,000 a year—far above the starting average of $14,700. “We want to create a case study for what place-based support looks like,” says Baxter.

As a “place-based” nonprofit, GOODProjects tailors its services to the multifaceted needs of a community rather than focusing on one symptom or cause of poverty. Because, as Baxter says, if you pour help into one issue in a resident’s life, they “still got to go to the same school that’s [messed] up or the same grocery store that’s not providing quality food or the same community with broken windows and people laid out on the street.”

Because of its holistic approach, GOODProjects’ services are vast (and often made possible by partnerships with other organizations): from a grocery-delivery program to a community health clinic to a six-week summer camp for kids to one-on-one mentoring.

“It’s about being intentional and having conversation with the community,” says Baxter, who regularly shares meals with parents and community members so he can hear their concerns.

Meals like these, he says, are among the most rewarding aspects of his work: “I find myself in this constant state of joy, because there’s no greater gift in life than to help those that are underserved. The thing I hear the most is ‘I can feel y’all love us.’ That’s been a blessing.”

Monty Hoffman

Founder and Chairman, Hoffman & Associates

Where some saw a wasteland, Monty Hoffman envisioned the Southwest DC waterfront as a bustling riverside hub that would one day rival San Francisco’s and Boston’s. The idea seemed a bit far-fetched at the time, but the developer was no stranger to beating the odds.

Hoffman arrived in Washington in 1984 with little in his pocket. He couch-surfed for six months until he landed an engineering gig at Donohoe Construction. One day, he and a coworker bought a townhouse in a crime-ridden neighborhood near Logan Circle to convert into six condominiums. People called them crazy, but the condos sold out in an instant. The duo quit their day jobs and founded PN Hoffman (now Hoffman & Associates), today one of the region’s largest developers. They rode the crest of the housing market, building condos all over Washington throughout the early 2000s. Then the market started to collapse and Hoffman’s partner left.

Not long after, an opportunity arose for Hoffman to join Baltimore-based Struever Bros. Eccles & Rouse for the bid to develop the Southwest DC waterfront. They won over more than a dozen competitors, but Struever Bros. ran into financial trouble and backed out.

That’s when Hoffman teamed up with commercial real-estate giant Madison Marquette. Almost a decade later, in 2017, the Wharf made its debut: apartments, condos, restaurants, hotels, shops, and music venues. The second phase was completed in 2022.

Hoffman says the biggest hurdle was changing the way people thought about the Southwest waterfront. That required what he calls “a big-bang theory,” in which he’d create a large presence with investors and tenants. It would take more than $1 billion, four acts of Congress, seven DC Council votes, and 800-plus meetings with Advisory Neighborhood Commissions and other community groups. “I had all these constituencies that I needed to bring together,” Hoffman says.

He was determined to keep neighborhood staples such as the Capitol Yacht Club and the Municipal Fish Market and bring in local shops and restaurants. “We needed something that was authentic,” he says. “Something that Washington and the whole nation could embrace.”

Hoffman estimates that nearly 8 million people have visited the Wharf over the past year alone. “It will soon no longer be a development,” Hoffman says. “People will think of it as a community and own it through their experiences.”

Shawn Yancy

NBC4 news anchor and founder, Giving Foundation for Women and Children

Shawn Yancy was pulling into the parking lot at Fox 5 on September 11, 2001, when American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon. It was just her second day on the job and a week since moving to DC from Pittsburgh. She and a photographer raced to the scene.

Yancy was frightened and devastated, but she remembers being moved as she covered the story. “In the days and weeks that came after, I got to meet the families that were touched by the horrific act and to witness the incredible love our community shared by coming together to support each other,” she says.

That experience inspired the young news anchor to approach every story from the viewpoint of the people affected, whether a teenager who won 50 scholarships or a family impacted by gun violence. Her reporting over the past two decades has earned multiple Emmys and a prestigious Edward R. Murrow Award.

Her work doesn’t end after the cameras stop rolling. When Yancy comes home late at night, she’s met with piles of clothes and toys in her living room, waiting to be donated to women and children in underserved communities. Fourteen years ago, she organized a clothing swap with a few girlfriends in her dining room. Whatever was left over was donated to a village in Liberia. She called it Girls’ Night Out and thought: “If we added a few more women, we could help more women.” Each year, additional people joined in, so she turned the swap into a big party whose proceeds would go to charities with similar missions to uplift women and kids.

What was once an annual gathering became a nonprofit called the Giving Foundation for Women and Children, with its own programs to provide essential items to those in need. In the past five years, the organization has donated not only clothing but thousands of hot meals, toys, and school supplies to families in the area and around the world. It also holds an annual Girls’ Night Out benefit gala with a bazaar of local shops and a DC-celebrity fashion show. The nonprofit has raised $180,000 since its inception.

“We’ve always believed that we’re stronger when we stand together,” Yancy says, “especially in helping women and children create pathways out of poverty.”

Tom Wilson

Forward, Washington Capitals

Tom Wilson has earned a reputation as the Capitals’ tough guy—a bone-crushing enforcer who makes opposing lineups tremble. But when he’s not body-checking opponents or burying rebounds in the back of the net, the 29-year-old forward is providing assists to neighbors in need.

“My parents raised me to be, first of all, a good person off the ice and [to] try and live with the right qualities,” Wilson says. “Obviously, on the ice I’m a bit of a different player.”

Among Wilson’s many charitable endeavors is 43’s Friends (the name comes from his jersey number), an organization that provides Capitals tickets to ailing children through Make-A-Wish Mid-Atlantic. Wilson welcomes the kids and their families into the Caps dressing room and introduces them to teammates. “This is something to try to put a smile on their face and let them be a normal kid,” Wilson says, “and just let them know we’re in their corner.”

Says Lesli Creedon, president and CEO of Make-A-Wish Mid-Atlantic: “He’s got this tough-guy, kind of bad-boy hockey-player image. But when he’s talking to these little kids, it just melts your heart. You can tell he really cares.”

43’s Friends also supports military servicemembers and their families, who are often kept apart by deployments. “This game,” Wilson says, “can be a time for the kids to come out—or when the dad or the mom gets home from overseas, [they can all] come out as a family and just have a really fun night.”

In addition, Wilson is an ambassador for Wolf Trap Animal Rescue, has traveled to local hospitals to visit with patients, has taken part in the Hockey Fights Cancer initiative, and has donated money that has benefited organizations such as DC Central Kitchen, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, and the Greater Washington Urban League.

“I’ve been part of this community since I was 19, and I’ve kind of grown up here,” he says. “I take huge pride in living in this city and being a part of this community, [so] any chance I can give back is super-important to me.”

Correction: This story has been updated to correct a previous version, which stated that Richard Reyes-Gavilan “created” the DCPL’s Books from Birth program. He did not create it but helped oversee its implementation.

This article appears in the January 2024 issue of Washingtonian.

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)