The last time I talked with Roni Stoneman, she was fired up about a show she had played with her sister Donna. In their 80s and game as ever, the Stoneman sisters still performed together like they had since childhood, mostly at benefits and special events. And this event was extra special.

It was an appearance at National Fiddlers Hall of Fame in Tulsa, where their brother Scott was being inducted posthumously. He had taught them both to play music, and they had stellar, history-making careers as the first women to play lead instruments in a bluegrass band: Roni on banjo, and Donna on mandolin.

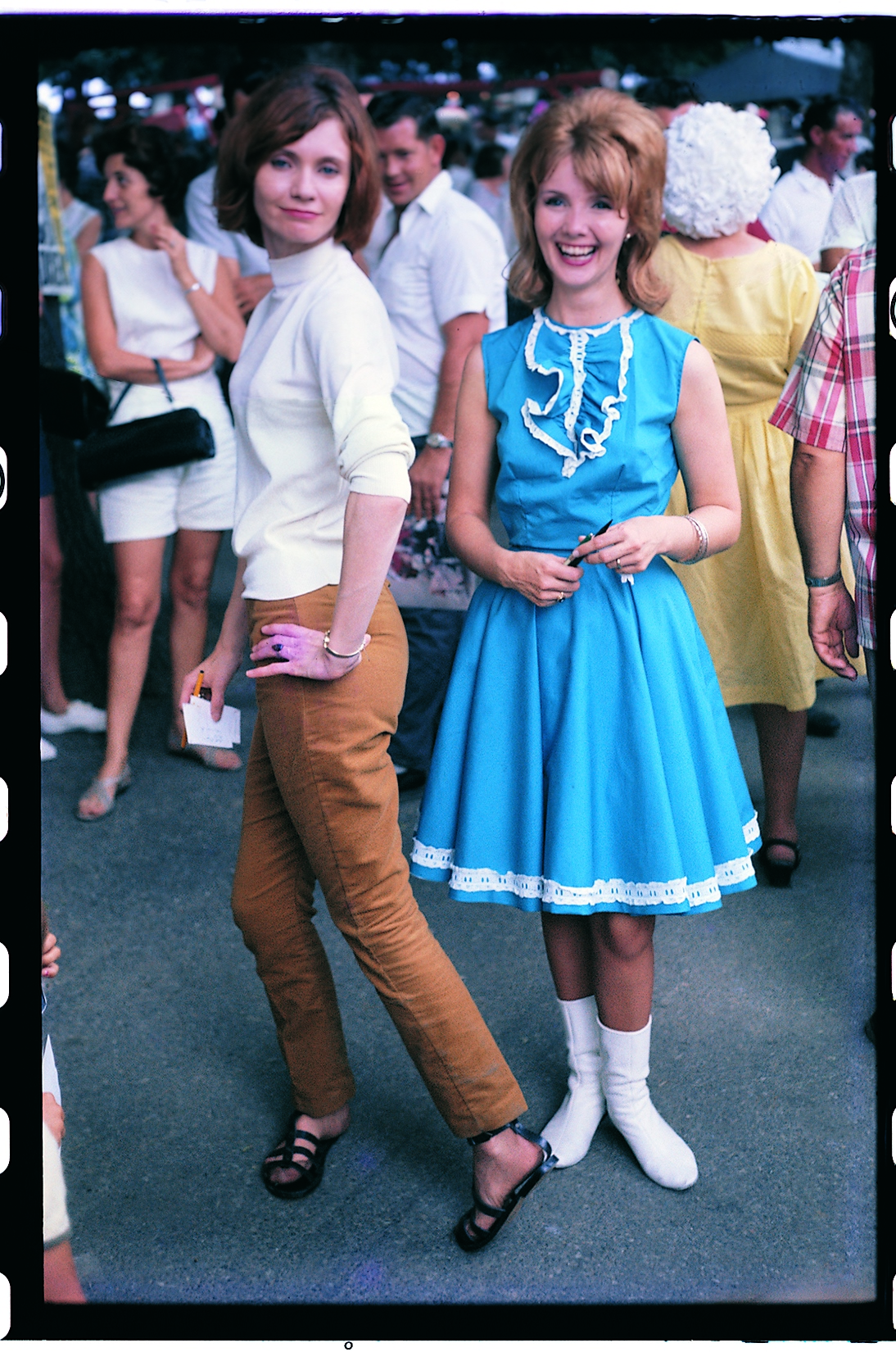

Scott was their mentor and their band mate and their hero, like he was for Jerry Garcia, who hailed Scott as “the bluegrass Charlie Parker.” In the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, Roni and Donna worked with Scott onstage six nights a week, five shows a night at The Famous, a rough honky-tonk in downtown DC, what Roni called a “skull orchard” for the brawls that often broke out.

Roni had told me stories about her brother’s intensity and feral energy onstage that echoed what I had heard from many musicians who shared the stage with him, like DC bluegrass great Bill Emerson, among others. But Roni’s visceral accounts went beyond the usual superlatives, and gave a picture of a once-in-a-generation music phenom in the heat of the moment, plying his craft for drunk sailors while bottles flew.

“Scott was the hardest-working musician I ever saw,” she said. “He didn’t just play a song, he attacked it. He put his whole heart and soul into it. Let me tell you what Scott did: He would sweat so bad, it would run down the tail-piece of the fiddle, and it would come apart because of the moisture. On the breaks in the kitchen, he’d say, ‘Roni, help me tape the bottom of my fiddle together.’ And I’d hold it real tight for him and he’d tape it up. He played many nights with his fiddle held together with electrical tape.”

Roni lived with the same intensity as her brother, and I was remembering her force-of-nature quality when news came of her passing at 85 last week in Nashville. I had gotten to know her well over the last two decades, when I wrote a book, Pure Country, and several feature stories on Roni and her family, DC’s legendary country-music clan of 23 children, many of them musicians.

Interviews with Roni were free-wheeling, punctuated by full-lunged renditions of songs and sound effects to make a musical point. She was unfiltered and strongly opinionated and no topic was off limits. She was the only person I knew whose favorite expletive was “Bull Hockey!” The topics ranged from contemporary country (“sissy”) to modern bluegrass (“prissy”) to the ability of her mother Hattie, and other mountain women like her friend Loretta Lynn, to foresee future events. Roni’s talk was a marvel, rooted in Southern oral traditions as old as the hills. It was a spontaneous combustion of archaic sayings mixed with her own salty slang and prone to long digressions. It was delivered rapid-fire at high volume, much like her signature banjo breaks.

So I was all ears when she told me about her trip to Tulsa to honor her brother Scott. It started out bad, with crappy accommodations, and got worse when she and Donna showed up for rehearsals for the induction ceremony. The way Roni told it, the event staffers snubbed the sisters like they were doddering old biddies, leaving them in the lurch without a fiddler to perform with.

“They figured we were too feeble to put on a decent show and not worth trifling with,” Roni said. “You know, too old to cut the mustard.” It was just the sort of situation the Stoneman sisters had faced their entire career, first as upstart women in a man’s world of hillbilly music, now as octogenarians stubbornly refusing to “act their age” and quit music for the retirement home. It wasn’t any use trying to explain that she and Donna had just recorded an album together and were actively performing.

Instead, Roni decided to have some fun with it. She gingerly hobbled onstage as if every step was a struggle, like the old Bag Lady in a Laugh-In skit. At the mike, she squinted into the crowd and meekly announced that the sisters were “up in years” but would try their best to manage a song or two without flubbing. Then, said Roni, she and Donna proceeded to put on a master clinic, Bluegrass 101: “The crowd was like to be in shock but they loved it,” she told me with a booming laugh. “We proved we didn’t need a fiddler to tear it up, nothing but ourselves.”

Growing up in the family’s one-room shack in Carmody Hills, just across the District line in Prince George’s County, Roni learned early on to make do with little. Her parents, Ernest and Hattie Stoneman, came from southwest Virginia, and they were among the first recording stars in the 1920s when country was marketed as hillbilly music. But they’d lost their fortune in the Depression and came to Washington for work like countless rural migrants.

Nothing got Roni riled up more than when her family legacy—especially that of her parents—did not get the respect and recognition she felt it deserved. In her later years, she became the family chronicler and preserver of mountain lore, and she kept a close watch on the Stonemans’ place in country history. In 2019, I interviewed her for a story on the Ken Burns’ documentary, Country Music. Though Pop Stoneman got a brief cameo, Roni felt he’d been given short shrift, and she was irate that Hattie had been ignored altogether. Naturally, it was the Carter Family with Mother Maybelle who got the spotlight, which rankled Roni to no end.

“It’s always Mother Maybelle! Mother Maybelle,” said Roni, scorching the phone line from Nashville. “Well, what about our mother? Where in the cat-hair is Hattie? Mama had been recording with Daddy on Edison years before the Carters. Well, piss on it. Tell ’em I said to go piss up a rope.” Then her voice in fine fettle, she began to sing an old-time tear-jerker recorded by Pop in his heyday, “Somebody’s Waiting For Me”; the family had performed the song when they won a talent show at DC’s Constitution Hall in 1947.

Roni was all too aware of the sacrifice her mother had to make in giving up music to raise the family. Hattie tried to maintain order in the house, often to no avail. Visitors recall her doing chores and dipping snuff and periodically shouting, “Lord God, Ernest!” as kid-triggered disasters detonated around her. Roni says that when she got her first banjo, made by Pop out of spare parts, Hattie was too busy with her unruly brood to give her lessons in the drop-thumb claw-hammer style that was part of the mountain music tradition for generations: “Mommy wouldn’t take time to teach me. She said, ‘Lord have mercy, honey, you don’t need to play the banjo!’”

Instead, Scott taught her the new banjo style that was all the rage, the dynamic bluegrass style popularized by Earl Scruggs. Roni became so proficient that at age 18 she became the first woman to record in the new style with her rendition of “Lonesome Road Blues.” It appeared on the landmark 1957 Folkways album, American Banjo: Three-Finger & Scruggs Style. In the liner notes, compiler Mike Seeger praised her “individual interpretation of the style,” adding, “Just as it is rare for women to play ‘bluegrass style’ music,’ it is even more rare for them to play this banjo style.” Roni, who was pregnant at the time, remembered Seeger’s respect and devotion for the grassroots music her family made—and the fact that he was the first person she ever saw wearing corduroy pants and sneakers.

Along with Scruggs, two of her favorite banjoists were Don Reno and Ralph Stanley; she did a blistering version of Stanley’s 1956 instrumental “Hard Times” that became a showpiece of her stage act. “I don’t like a tinny-sounding banjo, I like a big, clear tone and I like the roll where it never stops,” said Roni, who had no love for slick pickers she’d hear at bluegrass festivals. “These trained ones, that’s had all the music notes taught to them, they don’t put their personality into it. In the old days, you could tell who was playing by the roll. Nowadays you can’t tell anything. Something’s been lost.”

As the second-youngest of the Stoneman clan, Roni became the most famous thanks to her role as Ida Lee Nagger in the TV show Hee Haw in the ‘70s and ‘80s. The skits were trailer-trash caricatures but echoed her own tumultuous series of abusive marriages.

Once, we got to talking about the old-time musician, Ola Belle Reed, who ran a country-music park in Rising Sun, MD, where the Stoneman family often played on weekends. Reed came from the mountains of North Carolina and like the Stonemans had made a career playing hillbilly music for homesick migrants like herself near the Mason Dixon line.

It was the early ‘60s, and Roni was a working mother of young children with a deadbeat husband who mistreated her. Onstage, she put on a brave and happy face as the Stonemans’ star comedienne, but Ola Belle—two decades older and a good deal wiser—could see through the veneer. “I was trying to smile even when I had no money and nothing but troubles,” recalled Roni. “I’d be out there greeting with audience, flirting with the Amish boys. Later, she would see me standing there alone and she’d come over and say, ‘Roni, I need to talk to you.’”

Ola said she could tell that Roni was going through hard times in her personal life, and tried to give advice. Roni realized that Ola Belle had that same sort of uncanny gift that she had seen in her mother, Hattie, and her friend, country singer Loretta Lynn. “It takes a mountain woman to know the sorrows of people before you can do that,” she said. “It’s a special thing that some mountain folks have. Most men aren’t sensitive enough. It takes a mountain woman who’s gone through the trial and tribulations that a woman goes through. As the old folks say, she had a way of foretelling what was coming down the road for you.”

Ola Belle told Roni she would be suffering more abusive relationships unless she learned to stand up for herself. “She told me, ‘Don’t let ‘em do that!’ And I’m going ‘Huh?’ standing there just listening to her,” recalled Roni. “I was young and I didn’t’ know nothing. She knew I wasn’t being treated good and she knew what kind of husband I’d get next. She could tell I was going to step into a big pile the second time, and she was right. He was bad news. He was a high school principal—who would have ever thought? He beat on me and took drugs and did terrible things.”

Despite the string of bad marriages, there were many career triumphs as well. In 1969, Roni appeared on Glen Campbell’s Goodtime Hour TV show. She was the only female in an all-star banjo band that included Campbell, John Hartford, and a young Steve Martin, spearheading a six-banjo version of the traditional mountain tune, “Cripple Creek.”

In 1989, Roni was hitting her 50s in full stride as a solo artist. In the best DIY tradition, she released the self-produced, cassette-only First Lady of the Banjo, as she now billed herself. It featured a cover shot of Roni casually lounging Huck-Finn-style high in a tree with her banjo, a throwback to her tomboy days climbing the shade trees in Carmody Hills.

After she lost her job on Hee Haw in 1991 due to layoffs, she started an all-female country band, The Daisy Maes, a short-lived venture named for Li’l Abner’s wife in the cartoon strip. The band’s ill-starred run, which included good-ole-boy boo birds giving them hell at venues throughout the South, proved to Roni that audiences were not yet ready for “girls who could play better than the guys.”

In her final decades, Roni continued to tour and record. She made several albums for the local Patuxent label, including two with her sisters Donna and Patsy, who died in 2015. The most recent, The Legend Continues, was released in 2020 and featured Roni on a batch of family favorites with Donna, who survives her sister as the last Stoneman. “Those albums for Patuxent was our way of telling the young generation to look in on our music,” said Roni, “and to check out what we can do and not just what we did way back in the past. Too many dids! I was gonna name my new band Roni Stoneman and the Dids!”

Her passing leaves the country-music world one step closer to the Assembly-Line Auto-Tuned Hellscape of modern-day Nashville. This shallow, dumbed-down corporate product is alien from the homemade music made by three generations of the Stonemans, who as Roni liked to say, didn’t exactly get rich for their efforts. “The only thing that the Stonemans were made for is to entertain the people and never get paid,” she once told me. “That’s our claim to fame!”

Even so, the musical legacy of Roni Stoneman and her kinfolk was made to last, and it will endure, even as such roots music becomes ever more rare, as does the traditional Appalachian mountain culture (transplanted as it was) that made the extraordinary lives of Roni and the Stonemans possible. In the words of author Shelby Foote, writing about bluegrass-biker outlaw and old-time musician Jimmy Arnold, who hailed from the same part of southwest Virginia as the Stonemans: “Pretty soon, I fear, we’re going to run out of people like him and we’ll be much poorer for the loss.”

Those same words apply to Roni Stoneman—who would no doubt hear such high-falutin’ sentiments and shoot right back with all her contrarian might: “You ain’t as poor as us Stonemans were! Bull hockey on that!”