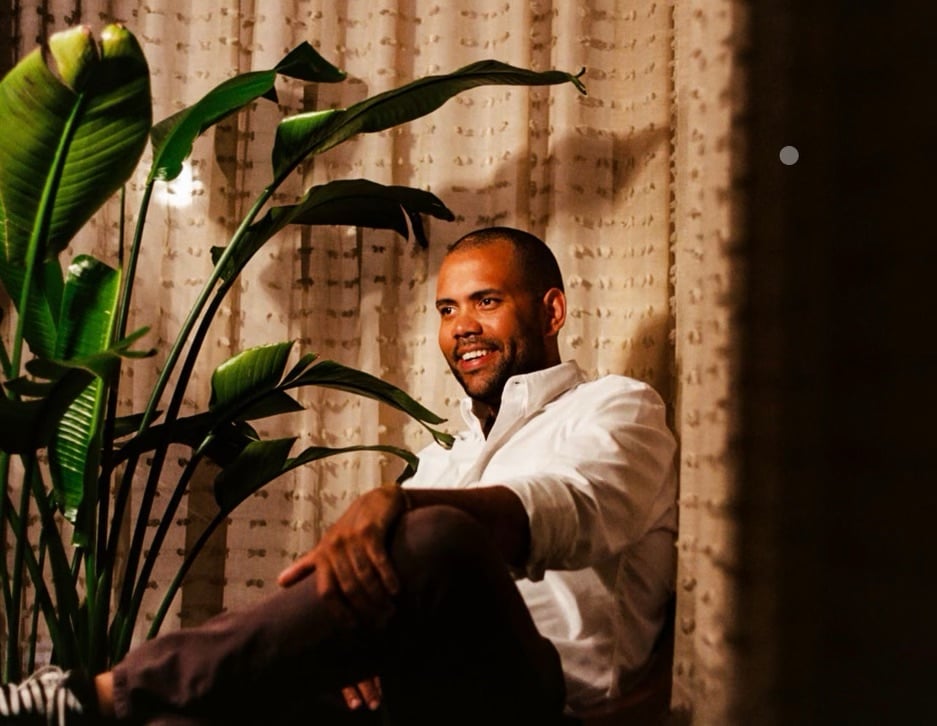

Robert Curtis, the former executive chef of Bourbon Steak who was preparing to open a Brazilian restaurant and bar in DC, has died. He was 35 years old. Friends, colleagues, and family remember him for being cool and collected, driven in his career but humble about his accomplishments, and generous with his time—but with a fun, silly side too.

“He set the bar so high for being a person,” his wife, Ursula Curtis, says. “Everyone of course thinks of him as having very high standards and setting the bar high as a chef and in the industry, but he was like that at home. He was like that as a partner, as a friend, as a son, as a brother.”

The cause of death has not been publicly disclosed.

Curtis was born in Philadelphia but grew up in Bethesda and DC. He cut his teeth working for Old Town fine-dining restaurants Brabo and Restaurant Eve before joining the Michael Mina’s Bourbon Steak, where he worked off and on, eventually becoming executive chef from 2020 to 2023. Curtis also spent a stint at Mina’s San Francisco restaurant RN74, went to Copenhagen to intern at world-famous Noma, and helmed Neighborhood Restaurant Group’s now-closed Hazel restaurant in Shaw, which received a Bib Gourmand designation from the Michelin guide.

Last year, Curtis became partner and culinary director at Unordinary Hospitality, which took over operations of South America-inspired Mercy Me in the West End. The group was preparing to open a Brazilian restaurant/bar called Cana in Adams Morgan this month.

“Everyone loved working with Rob,” says Albi chef Michael Rafidi, who cooked with Curtis at RN74 and had tried to recruit him for his own restaurant. “He was so calm. He was the nicest chef and the most balanced chef in the kitchen. He was the guy who was holding shit together. He was really one of the better cooks I’ve ever worked with.”

Caruso’s Grocery chef Matt Adler, who worked with Curtis at Neighborhood Restaurant Group, likewise remembers Curtis for his calm, stoic demeanor. In the early days of the pandemic when they were helping to run a grocery and pantry delivery service, Adler recalls how Curtis had prepared around 125 date-night dinners for two. Then the refrigeration went out over night, ruining the meals. “Any other chef I think I’ve ever met in my life would have freaked out, would have been upset or screaming or yelling. But Robert was just like, ‘No big deal. We’ll do it again next week. This shit happens, and we’ll figure it out.'”

The Bazaar by José Andrés chef David Testa, another former colleague from NRG, remembers Curtis as a grounding presence and leader-by-example amid the uncertainty of the pandemic, when Hazel closed and he was thrown into helping with Bluejacket brewery and opening the Roost food hall in Capitol Hill. Testa says he even jumped on the line to help with the Roost’s taqueria opening: “Even though it was tacos and nothing like Robert Curtis’s forté by any means, he created beautiful plates. He rocked it out and had a blast doing it… He just had the biggest smile on his face.”

Other former colleagues also remember Curtis as a versatile chef, whether it was honing his French cooking at RN74, exploring Turkish flavors at Hazel, and more recently diving into Brazilian cuisine for Cana.

“He could do it all, in a way, without dropping quality,” says David Van Meerbeke, the director of operations for Yellow who got to know Curtis as a sous chef at Bourbon Steak when he was general manager there. Years later, Van Meerbeke still remembers a North African-spiced steak tartare from a tasting with the chef.

“It felt like everything he put up was ready to go on a menu. And it probably was because he was immensely talented. But he probably did do the work on the back end, too,” Van Meerbeke says. “His food was some of the best, in my opinion.”

Curtis was quietly generous, too. Kylin Brady, a captain at Bourbon Steak, recalls a particularly rough dinner service. She’d recently moved from Florida to DC and was missing her mom and brother, who Curtis knew she was close to and would often ask her about. So, at the end of the night, he handed her a to-go bag with a fully cooked dinner. “He told me he knew it wasn’t the same as having them here with me but just a little something to make me feel less lonely. Such a simple gesture, but it left an imprint on my heart,” Brady says.

At Bourbon Steak, Curtis was among a group of local chefs who opened their kitchens to create dishes with kids who have intellectual or developmental disabilities as part of a Best Buddies program. Chefs Stopping AAPI Hate executive director Pamela Yee says she got to know Curtis when he donated a private dinner to raise money for victims of the Monterey Park mass shooting, and he continued to help her out even with gift cards for her kids’ school fundraiser.

“Some chefs chase all the awards, the accolades, and all that. For him, it was just he wanted you to come in. He wanted the connection. He wanted you to come in for the birthday. He wanted you to get fed and have a good time,” Yee says. “He was quiet, but he made such an impression.”

Ursula, Curtis’s wife, says he had a silly side too. The couple took holiday cards with matching outfits to the next level, sending out goofy photo postcards of themselves for Fourth of July, National Hawaiian Shirt Day, and National Donald Duck Day. “He was a Michelin chef but also a meme lord, and I just loved the duality there,” she says.

Ursula says he had a lot of passions outside the kitchen: he was a trivia whiz, traveled frequently, dug style and design, loved DC punk music but also poetry, and could read tarot cards. “He was pretty spiritual. I’m not sure a lot of people knew that.”

He also loved to surprise her at the airport when she was coming back from a work trip or have a bottle of wine or dessert sent to her if she went out to dinner.

“He just went above and beyond, and he was so caring and just so nurturing. He was like that really with everyone in his circle,” Ursula says. “He was so loved by so many people.”