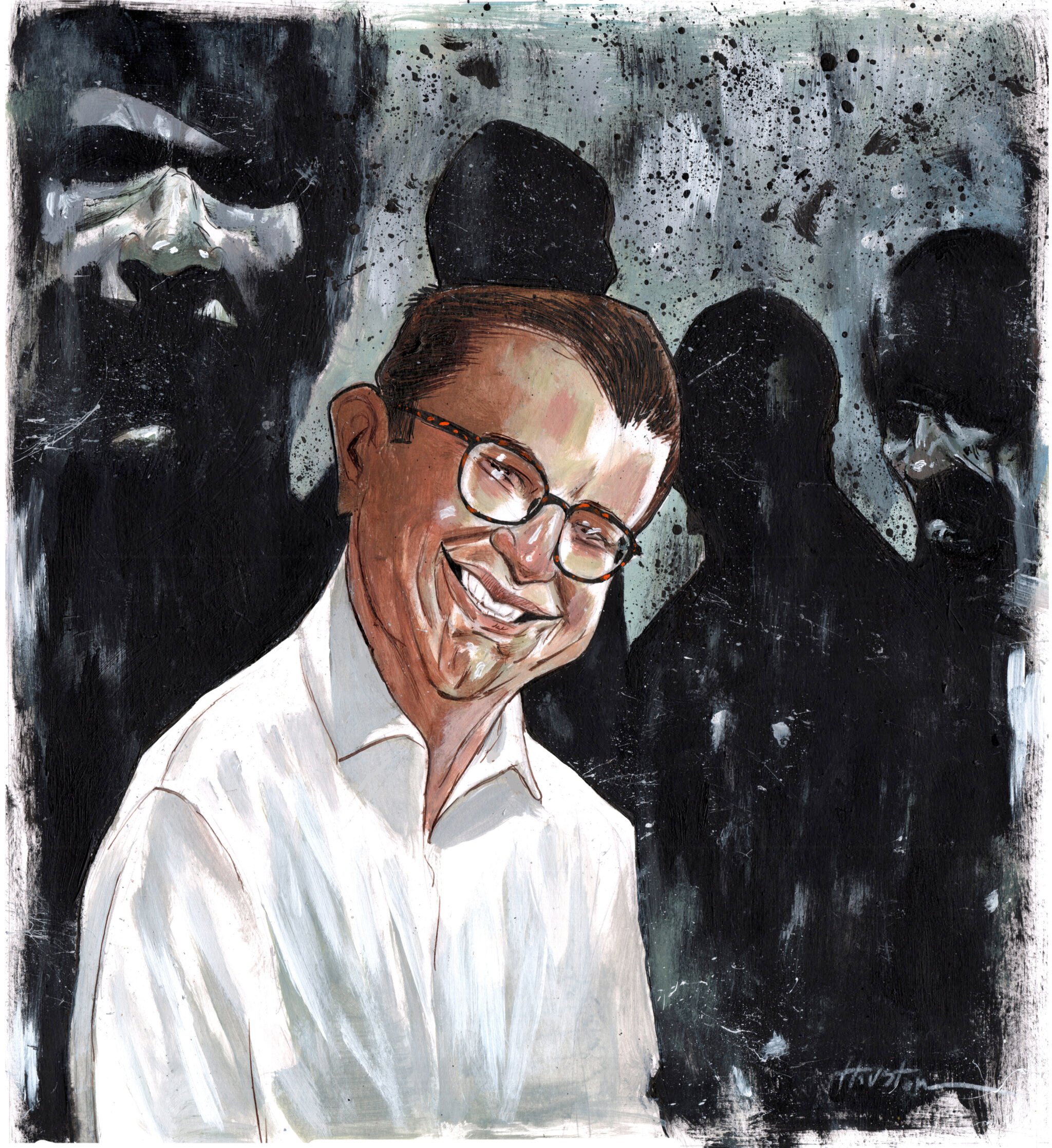

Phil Elwood is consummately nondescript: mid-forties white guy, checked button-down, jeans and sneakers, military-style buzz. “I have the most benign glasses,” he says. “I look like every other dude in DC.” It’s deliberate. For his whole career as a public-relations operative, Elwood’s goal was to shape the news from the shadows, and to avoid becoming the story himself.

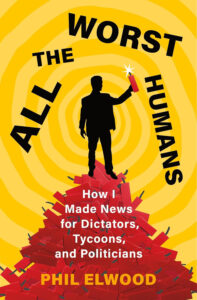

Now Elwood is stepping into the light. In July, I met him at Joe’s Stone Crab—a boozy lunch joint by the White House—to talk about his new book, All the Worst Humans. It’s a mid-career memoir that is, in simple terms, an account of his decade or so of reputation-laundering for various dastardly regimes, including the Gaddafis and the Assads. It’s basically the PR industry’s Kitchen Confidential, a dissection of the profession’s grittier corners. The book is shocking, gross, dark, and funny. It’s self-deprecating and self-mythologizing at once.

But All the Worst Humans is also, in Elwood’s telling, a bit of a career refresh—a way to burn bridges so that he can no longer do the kind of work he once did, plus an attempt to bring some of the shadiest practices of his industry to light. “People come to me all the time and ask me to do things that are whack,” he said. “But I wanted to stop myself. I don’t want to get away with that stuff anymore. I don’t want to have to answer the question ‘Will you work for this baddie?’ ”

When Elwood says that, it’s a little tough to know what to think. He’s a seasoned PR operative; his expertise is spinning reporters to write favorable stories for his clients. It’s not lost on me, as we eat shrimp cocktail at the bar, that in this case, his client is him.

Here is, in broad terms, Elwood’s story: After a peripatetic childhood, he won a debate scholarship to the University of Pittsburgh, developed a drug problem, then dropped out in 2000. Instead of going to rehab, he moved to DC, landing—through a friend—an internship with Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, which he parlayed into a job with Senator Carl Levin. While working on the Hill, he graduated from Georgetown University, then got a master’s at the London School of Economics. When he returned to DC, he found a job in PR.

At first, the work was typical; Elwood was asked, for example, to try to influence the MPAA rating for an expletive-laden Iraq War documentary. An R rating could depress ticket sales, so he concocted a moral argument: that the film must be PG-13 because teens who might consider enlisting should be able to see what horrors await. The filmmakers presented Elwood’s case to the MPAA, which voted to rate it PG-13.

Later, Elwood moved to a megafirm with lots of clients overseas, entering a nook of the PR world that’s known—somewhat euphemistically—as “private-sector international relations” or “public diplomacy.” His first dodgy assignment, back in 2008, was for the Libyans. He was sitting at dinner when a text arrived from his boss ordering him to drop everything and check his email. There he found an op-ed from Muammar Gaddafi. Elwood was to edit what he calls “600 words of crazy” into something coherent enough to print, then send it to whichever paper would run it the fastest. A few days later, Elwood’s wordsmithing ran under Gaddafi’s byline in a national publication, castigating the West for “provoking Russia,” which had invaded Georgia just a few months before.

The work Elwood did earned him a subpoena from the Robert Mueller investigation. The subpoena, now framed, hangs in his bathroom.

From there, Elwood embarked on a decade of high-stakes PR capers—stunts that often looked more like diplomatic maneuvering than managing a client’s image. In 2010, Elwood used a dormant nonprofit, a fat check to a lobbyist, and a never-passed congressional resolution to help torpedo the American World Cup bid on behalf of Qatar. A couple years later, when a US anti-gambling law thrashed the economy of Antigua, he fought it by provoking a trade war. And then came his work for an Israeli firm called Psy-Group, which pitched the 2016 Trump campaign on a plan to use social media to influence the election. (Elwood insists he wasn’t involved in that effort, and the Trump team apparently turned them down.)

The work Elwood did for Psy-Group—moving enormous sums of money between dummy corporations, printing and delivering mysterious documents—earned him a subpoena from the Robert Mueller investigation. He says that when word trickled out, his client roster dried up, though he was never personally accused of any wrongdoing. The subpoena, now framed, hangs in his bathroom.

Despite his insouciance, Elwood doesn’t feel great about many of his former clients. So why, one might ask, did he get involved? “It didn’t exactly register for me what I was doing,” he told me. “The thing I would compare it to is skydiving; when you get to the door and you’re about to jump out of the airplane, you look out at the curvature of the earth and everything below isn’t real. Your brain can’t process it. It’s kind of like a cartoon.”

Elwood loves skydiving, by the way. He encouraged me to go.

In All the Worst Humans, PR is a little like sleight of hand; if done well, its mechanics are invisible. In 2009, for instance, the Lockerbie bomber—a Libyan terrorist who’d helped bring down a Pan Am flight over Scotland—was about to be released from prison. He murdered 270 people, but the Libyan government wanted him to receive some good press.

Elwood hatched a plan: He drafted an open letter—making the case that Libya was America’s ally in the war on terror, so it was important not to bash them too hard—then found a member of Congress who was willing to sign it. (Elwood told that member’s staff that alienating Libya might undo important diplomatic work.) Then Elwood took the story to Politico, which printed a news item with excerpts of the letter—evidence of a Libya-friendly element within the US government—without any mention that Gaddafi himself was behind it.

Elwood describes his work as building Rube Goldberg machines. “You have to think in this strange way of ‘Can I get the ball to bounce off the strings and start a fire in order to lead to this particular outcome?’ ” Some of it, he admits, is obfuscation. In the past, when feeding a reporter a story, he would sometimes hide the identity of his client, concealing whom the story might benefit. “Now, if a client comes to me and says, ‘No one can find out who I am,’ I won’t take the account. I’m like, ‘I’ve got to be able to tell reporters who’s paying my bills.’ ”

Early in the book, Elwood explains that during their training, PR operatives learn that every story has a villain, a victim, and a vindicator (a hero, essentially). Often, a PR guy’s job is to tell a story that turns the villain into a victim or vindicator—a murderer becomes heroic, Elwood writes, if his crime was meant to protect someone else.

The obvious question, then, is whether that’s the point of Elwood’s book: A mouthpiece for foreign dictators seems like a villain, but a crusading operative, torching his industry in service of reform, is a hero. Perhaps he wants to change the narrative—he did stress that he wrote the book, at least in part, to try to improve his profession, encouraging PR people to ask themselves whether what they’re doing is right and prodding journalists to be savvier about where they’re getting tips.

But as Elwood flirts with virtue, he still seems to love a villain. During our interview, he talked a lot about his cat, a longtime pound straggler with a reputation for attacking children. He named that cat Darth Vader.

At Joe’s, Elwood picked at his crab Louis salad, and I noticed a Band-Aid on his hand. When I asked about it, he said it was a relic of a ketamine infusion 48 hours prior; he wears it for three days after each treatment to remind himself not to drink, because alcohol reduces the efficacy of the drug.

Elwood credits ketamine with saving his life. In the aftermath of the Mueller ordeal, he was underemployed, spiraling, and convinced that his wife was going to leave him. Eventually, he attempted suicide at his weekend house on the Eastern Shore. After that, he found ketamine (which reduces his suicidal ideation), worked to get healthy, and decided to stop laboring toward morally dubious ends. Now that he’s properly medicated, he says, that kind of work no longer appeals.

“So you were self-medicating with adrenaline by working for the Gaddafis?” I asked.

“Yes,” he replied. “I was treating bipolar disorder with risk.”

Today, Elwood still does PR, but he insists that he works only for good guys—stuff that’s pro-democracy, causes that would make his wife proud and wouldn’t raise eyebrows with his lawyer. Elwood currently has just one primary client, and he would only tell me who it is off the record. He said he didn’t have authorization to reveal it in this article, and he worried that going public would limit his options in terms of the story he’s trying to tell on their behalf. But he needed me to believe that he’s changed his ways—that he’s working for someone virtuous—which would be tough if I didn’t know who it was.

When PR people want to influence the tone or direction of a story without leaving any fingerprints—without the reporter being able to use the information in print—they ask to talk off the record. (Off-the-record discussions, Elwood says, account for 99 percent of his job.) He calls this the Faustian bargain at the heart of his industry. “If reporters don’t talk to me, they’re not going to get the information, and the story won’t be as good,” he said. “But if they do talk to me, they’re talking to somebody who’s been paid by a third party to advance an agenda.” When Elwood offered to name his client off the record, I let him. And as he intended, it bolstered his case that he’s reformed. But because I allowed him to go off the record, readers can’t judge for themselves.

One might think that writing a book like Elwood’s—airing the dirty laundry of a cash-drenched industry whose whole job is to burnish reputations—might generate some blowback. But so far, there hasn’t been a negative response. Actually, Elwood said, a lot of PR folks have thanked him for not including them. “Nobody wants their name to appear in a book called All the Worst Humans,” he told me.

But if the book didn’t upset people, did it really burn bridges? How do we believe that Elwood is done working for baddies, that he hasn’t actually hung out a shingle, letting the world know that he’s up for these kinds of jobs? “Because I said in the book that I wouldn’t, and people can keep me accountable,” he replied. “If I ever call you and I’m like, ‘Hey, I’m working for this very misunderstood despot,’ write me up. Blow me away. I deserve it.”

Phil Elwood is consummately nondescript: mid-forties white guy, checked button-down, jeans and sneakers, military-style buzz. “I have the most benign glasses,” he says. “I look like every other dude in DC.” It’s deliberate. For his whole career as a public-relations operative, Elwood’s goal was to shape the news from the shadows, and to avoid becoming the story himself.

Now Elwood is stepping into the light. In July, I met him at Joe’s Stone Crab—a boozy lunch joint by the White House—to talk about his new book, All the Worst Humans. It’s a mid-career memoir that is, in simple terms, an account of his decade or so of reputation-laundering for various dastardly regimes, including the Gaddafis and the Assads. It’s basically the PR industry’s Kitchen Confidential, a dissection of the profession’s grittier corners. The book is shocking, gross, dark, and funny. It’s self-deprecating and self-mythologizing at once.

But All the Worst Humans is also, in Elwood’s telling, a bit of a career refresh—a way to burn bridges so that he can no longer do the kind of work he once did, plus an attempt to bring some of the shadiest practices of his industry to light. “People come to me all the time and ask me to do things that are whack,” he said. “But I wanted to stop myself. I don’t want to get away with that stuff anymore. I don’t want to have to answer the question ‘Will you work for this baddie?’ ”

When Elwood says that, it’s a little tough to know what to think. He’s a seasoned PR operative; his expertise is spinning reporters to write favorable stories for his clients. It’s not lost on me, as we eat shrimp cocktail at the bar, that in this case, his client is him.

Here is, in broad terms, Elwood’s story: After a peripatetic childhood, he won a debate scholarship to the University of Pittsburgh, developed a drug problem, then dropped out in 2000. Instead of going to rehab, he moved to DC, landing—through a friend—an internship with Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, which he parlayed into a job with Senator Carl Levin. While working on the Hill, he graduated from Georgetown University, then got a master’s at the London School of Economics. When he returned to DC, he found a job in PR.

At first, the work was typical; Elwood was asked, for example, to try to influence the MPAA rating for an expletive-laden Iraq War documentary. An R rating could depress ticket sales, so he concocted a moral argument: that the film must be PG-13 because teens who might consider enlisting should be able to see what horrors await. The filmmakers presented Elwood’s case to the MPAA, which voted to rate it PG-13.

Later, Elwood moved to a megafirm with lots of clients overseas, entering a nook of the PR world that’s known—somewhat euphemistically—as “private-sector international relations” or “public diplomacy.” His first dodgy assignment, back in 2008, was for the Libyans. He was sitting at dinner when a text arrived from his boss ordering him to drop everything and check his email. There he found an op-ed from Muammar Gaddafi. Elwood was to edit what he calls “600 words of crazy” into something coherent enough to print, then send it to whichever paper would run it the fastest. A few days later, Elwood’s wordsmithing ran under Gaddafi’s byline in a national publication, castigating the West for “provoking Russia,” which had invaded Georgia just a few months before.

The work Elwood did earned him a subpoena from the Robert Mueller investigation. The subpoena, now framed, hangs in his bathroom.

From there, Elwood embarked on a decade of high-stakes PR capers—stunts that often looked more like diplomatic maneuvering than managing a client’s image. In 2010, Elwood used a dormant nonprofit, a fat check to a lobbyist, and a never-passed congressional resolution to help torpedo the American World Cup bid on behalf of Qatar. A couple years later, when a US anti-gambling law thrashed the economy of Antigua, he fought it by provoking a trade war. And then came his work for an Israeli firm called Psy-Group, which pitched the 2016 Trump campaign on a plan to use social media to influence the election. (Elwood insists he wasn’t involved in that effort, and the Trump team apparently turned them down.)

The work Elwood did for Psy-Group—moving enormous sums of money between dummy corporations, printing and delivering mysterious documents—earned him a subpoena from the Robert Mueller investigation. He says that when word trickled out, his client roster dried up, though he was never personally accused of any wrongdoing. The subpoena, now framed, hangs in his bathroom.

Despite his insouciance, Elwood doesn’t feel great about many of his former clients. So why, one might ask, did he get involved? “It didn’t exactly register for me what I was doing,” he told me. “The thing I would compare it to is skydiving; when you get to the door and you’re about to jump out of the airplane, you look out at the curvature of the earth and everything below isn’t real. Your brain can’t process it. It’s kind of like a cartoon.”

Elwood loves skydiving, by the way. He encouraged me to go.

In All the Worst Humans, PR is a little like sleight of hand; if done well, its mechanics are invisible. In 2009, for instance, the Lockerbie bomber—a Libyan terrorist who’d helped bring down a Pan Am flight over Scotland—was about to be released from prison. He murdered 270 people, but the Libyan government wanted him to receive some good press.

Elwood hatched a plan: He drafted an open letter—making the case that Libya was America’s ally in the war on terror, so it was important not to bash them too hard—then found a member of Congress who was willing to sign it. (Elwood told that member’s staff that alienating Libya might undo important diplomatic work.) Then Elwood took the story to Politico, which printed a news item with excerpts of the letter—evidence of a Libya-friendly element within the US government—without any mention that Gaddafi himself was behind it.

Elwood describes his work as building Rube Goldberg machines. “You have to think in this strange way of ‘Can I get the ball to bounce off the strings and start a fire in order to lead to this particular outcome?’ ” Some of it, he admits, is obfuscation. In the past, when feeding a reporter a story, he would sometimes hide the identity of his client, concealing whom the story might benefit. “Now, if a client comes to me and says, ‘No one can find out who I am,’ I won’t take the account. I’m like, ‘I’ve got to be able to tell reporters who’s paying my bills.’ ”

Early in the book, Elwood explains that during their training, PR operatives learn that every story has a villain, a victim, and a vindicator (a hero, essentially). Often, a PR guy’s job is to tell a story that turns the villain into a victim or vindicator—a murderer becomes heroic, Elwood writes, if his crime was meant to protect someone else.

The obvious question, then, is whether that’s the point of Elwood’s book: A mouthpiece for foreign dictators seems like a villain, but a crusading operative, torching his industry in service of reform, is a hero. Perhaps he wants to change the narrative—he did stress that he wrote the book, at least in part, to try to improve his profession, encouraging PR people to ask themselves whether what they’re doing is right and prodding journalists to be savvier about where they’re getting tips.

But as Elwood flirts with virtue, he still seems to love a villain. During our interview, he talked a lot about his cat, a longtime pound straggler with a reputation for attacking children. He named that cat Darth Vader.

At Joe’s, Elwood picked at his crab Louis salad, and I noticed a Band-Aid on his hand. When I asked about it, he said it was a relic of a ketamine infusion 48 hours prior; he wears it for three days after each treatment to remind himself not to drink, because alcohol reduces the efficacy of the drug.

Elwood credits ketamine with saving his life. In the aftermath of the Mueller ordeal, he was underemployed, spiraling, and convinced that his wife was going to leave him. Eventually, he attempted suicide at his weekend house on the Eastern Shore. After that, he found ketamine (which reduces his suicidal ideation), worked to get healthy, and decided to stop laboring toward morally dubious ends. Now that he’s properly medicated, he says, that kind of work no longer appeals.

“So you were self-medicating with adrenaline by working for the Gaddafis?” I asked.

“Yes,” he replied. “I was treating bipolar disorder with risk.”

Today, Elwood still does PR, but he insists that he works only for good guys—stuff that’s pro-democracy, causes that would make his wife proud and wouldn’t raise eyebrows with his lawyer. Elwood currently has just one primary client, and he would only tell me who it is off the record. He said he didn’t have authorization to reveal it in this article, and he worried that going public would limit his options in terms of the story he’s trying to tell on their behalf. But he needed me to believe that he’s changed his ways—that he’s working for someone virtuous—which would be tough if I didn’t know who it was.

When PR people want to influence the tone or direction of a story without leaving any fingerprints—without the reporter being able to use the information in print—they ask to talk off the record. (Off-the-record discussions, Elwood says, account for 99 percent of his job.) He calls this the Faustian bargain at the heart of his industry. “If reporters don’t talk to me, they’re not going to get the information, and the story won’t be as good,” he said. “But if they do talk to me, they’re talking to somebody who’s been paid by a third party to advance an agenda.” When Elwood offered to name his client off the record, I let him. And as he intended, it bolstered his case that he’s reformed. But because I allowed him to go off the record, readers can’t judge for themselves.

One might think that writing a book like Elwood’s—airing the dirty laundry of a cash-drenched industry whose whole job is to burnish reputations—might generate some blowback. But so far, there hasn’t been a negative response. Actually, Elwood said, a lot of PR folks have thanked him for not including them. “Nobody wants their name to appear in a book called All the Worst Humans,” he told me.

But if the book didn’t upset people, did it really burn bridges? How do we believe that Elwood is done working for baddies, that he hasn’t actually hung out a shingle, letting the world know that he’s up for these kinds of jobs? “Because I said in the book that I wouldn’t, and people can keep me accountable,” he replied. “If I ever call you and I’m like, ‘Hey, I’m working for this very misunderstood despot,’ write me up. Blow me away. I deserve it.”

Illustration of Elwood based on photograph by Christa Hamilton.

This article appears in the September 2024 issue of Washingtonian.