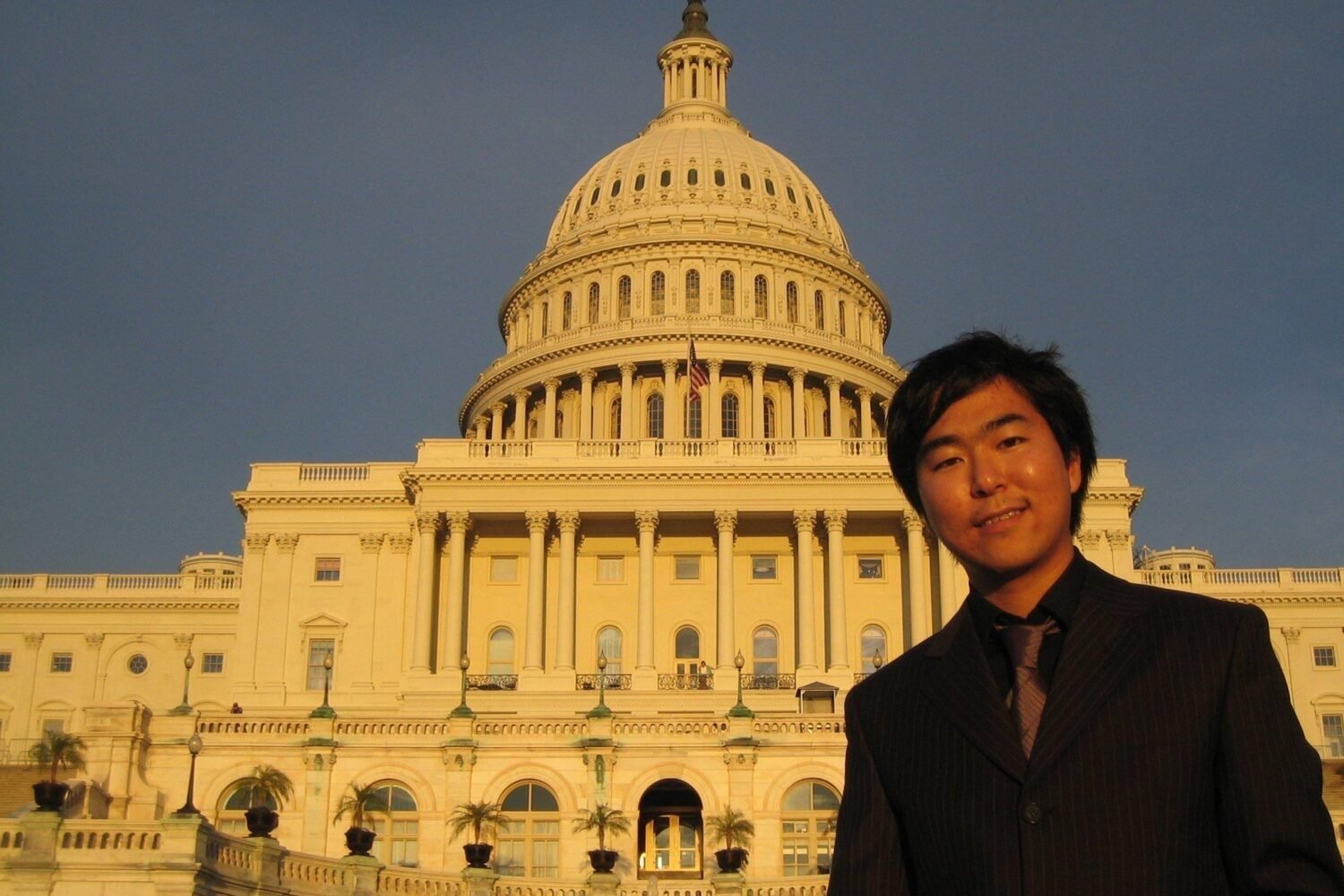

Maurice Edington, president of the University of the District of Columbia, has outsize ambitions for his school. For decades, UDC struggled with declining enrollment and a weak reputation—but Edington envisions it becoming a jewel of the city, a prestigious destination for students and researchers nationwide. To achieve this, the school recently rolled out a bold strategic plan that involves modernizing campus buildings, investing in research initiatives, and—crucially—improving graduation rates by helping students succeed in school. “Those aren’t fantasy goals,” he told me when we met in an airy campus boardroom. “We intentionally set ambitious goals that are doable. I want you to hold us accountable.”

A chemist by trade, Edington has spent most of his career in university administration, and he’s especially passionate about historically Black colleges. In his previous role at Florida A&M University, he shepherded the school up the U.S. News & World Report rankings; it’s now their number-one public HBCU. At UDC, where Edington has been president since 2023, he’s aiming for similar results. Coming to UDC, he says, was a calling: “I want to provide people like me—who didn’t grow up with a lot of money and support—with the best opportunity to be successful.”

What do you want the public to know about your goals for UDC?

I want people to understand that we are trying to transform ourselves into a national leader. I want to be best-in-class. One day I want you to say, “UDC is a very high-quality institution. I want my child or grandchild to go there. I want to donate money to them. I want to attend an event on their campus—a concert or a basketball game—because I’m proud of my flagship institution.”

And what do you think people most misunderstand about the school?

Many people don’t understand that we are more than a community college. Nobody really pays attention to the four-year, master’s, doctoral, and professional programs. The other is that there’s very little awareness that UDC is an HBCU, so we’re probably losing people who think that their only options are Morgan State, Bowie State, or Delaware State. But they can get most of the same things here.

Growing up, was there a culture of going to college in your family?

In our family, there was not a history of anyone going to college. The goal was to finish high school—that was a significant achievement. I have two older brothers, and our parents had issues with drug addiction, so when I was very young, they took us to our grandparents’ house in Berkeley, and that’s where we grew up.

In the ’80s, there was the crack epidemic, and a lot of my family—some cousins and uncles—were in that world. But my saving grace was that I loved school. I loved learning. I got to high school, and UC Berkeley was right there. I’d go up there all the time and hang out with my friends, but there was a disconnect for me. I didn’t ever see myself there—or even in college at all.

But then the TV show A Different World came on. Remember The Cosby Show? It had a spinoff about one of the daughters going to an HBCU. The first episode I saw, it just mesmerized me. I literally went to school the next day and asked a classmate, “Is that real?” She said, “Yes, there’s real schools just like that.” I was like, “I’ve got to get out of this environment,” and an HBCU seemed like such a nurturing space. That’s what gave me some hope about going to college.

You did go to an HBCU, Fisk University. How did that change you?

Fisk surrounded me with people from primarily middle-class backgrounds. On the first day, I was intimidated. I remember saying, “I don’t know if I can make it here.” But I started going to class and saw that my capabilities exceeded most of the other students. So I’m like, Oh, I could be successful. My professors really took an interest in me and gave me confidence.

When I started college, I had $400 to my name and a duffel bag. About a month in, I realized that I didn’t have enough money. So I went to this chemistry professor and said, “Hey, if I do well this year, can I get a scholarship for next year?” She said, “You don’t have a scholarship?” A week later, financial aid called the telephone in the dorm. They’re like, “You have a scholarship now.” That changed my life. This woman advocated for me, and I was able to remain in college. And that’s why I ended up [working] in higher education. I always felt like I had an obligation to give back.

At UDC, the graduation rate is around 40 percent. When students fail to graduate, why does that happen?

In general, there’s two major contributing factors. One is financial. Students can come here the first semester, but over time if they don’t have support from home or financial aid, it can be an impediment to progress. Another has to do with student preparedness. Some of these students are not college-ready and they don’t necessarily have the motivation or persistence, so they wash out.

Students are struggling academically in ways they didn’t before Covid.

During those years that were disrupted, students missed foundational skills. Some of them show up to college not having fully developed critical-thinking and reasoning skills and not having mastered basic concepts, whether it’s math, reading, or composition. Across America, we’re seeing these gaps, so you have to try to remediate them. The curriculum is not designed for students with those deficiencies. That’s a major challenge, particularly in public institutions, where you’re serving people in communities who were more adversely impacted.

There’s also something about grit and persistence. It’s very anecdotal—I don’t have any data on this—but people were [once] very motivated about overcoming their obstacles, and that has changed, I think.

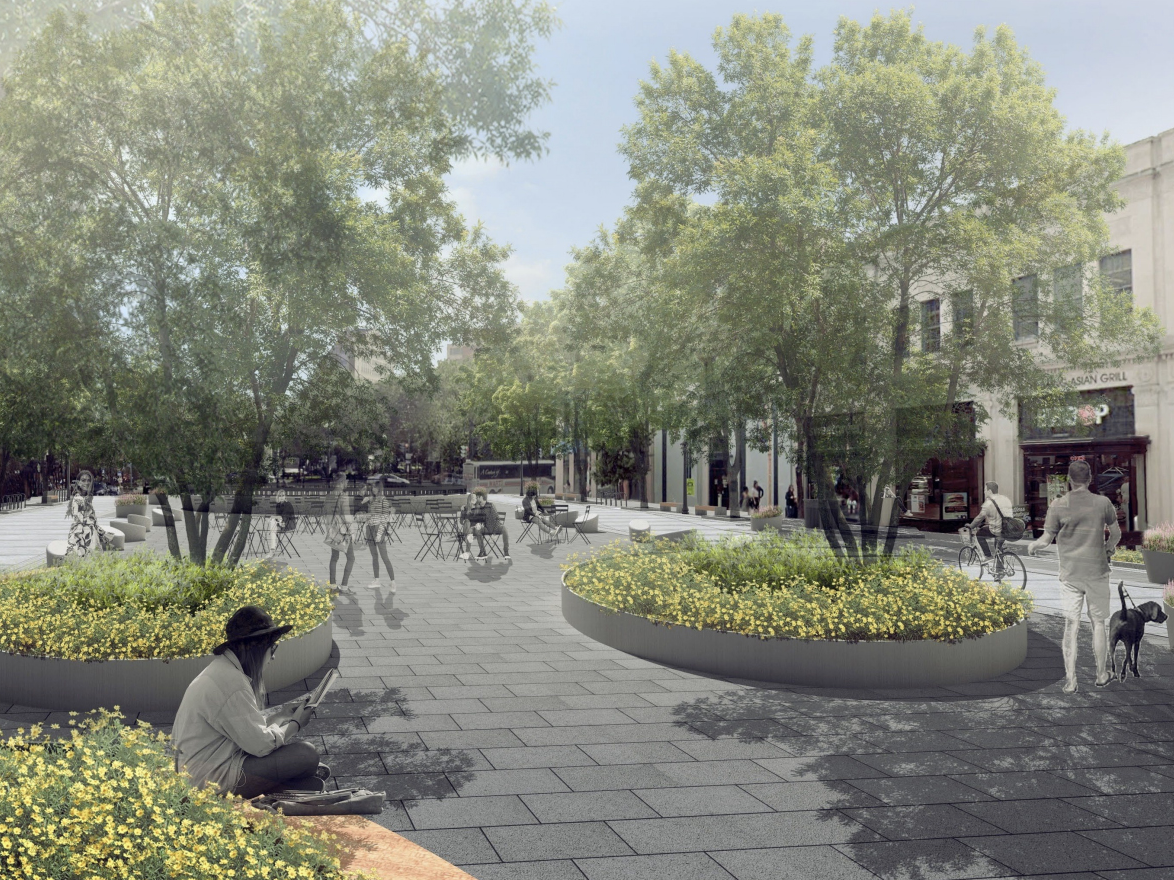

Part of UDC’s strategic plan seems more aesthetic than academic: rebranding, building new buildings. How does that align with academic goals?

It’s very important. This place has to look like a high-quality institution. You can’t come here as a student or parent and look around and see that our facilities are not on par with your high school. Psychologically, you’re like, “They can’t give me a high-quality education if they don’t have high-quality facilities.” Not every building has to be new, but there are certain things people look for. We now have a library that is very modern. It’s impressive. When you come and look at our school, you say, “Oh, this is where I’ll be using my time to study and learn.”

A large portion of people don’t even know there is a university called the University of the District of Columbia.

What about branding?

When you go to a campus, you expect to see the college brag about itself with flags and posters and signs. That’s going to start in 2025. And then marketing: We are very focused on increasing awareness. I would say that the overwhelming majority of the community doesn’t really understand what’s going on at this university. A large portion of people don’t even know there is a university called the University of the District of Columbia.

I remember coming for my interview, and I thought, “You never see the institution anywhere—like, there’s no signs, there’s no [ads on] buses.” So that’s an opportunity. People will say, “Oh, I didn’t know I could go there and get a PhD in computer science and engineering.” Then they’ll start thinking, “Let me learn a little bit more [about UDC].”

UDC is an HBCU, but you’re trying to position it as DC’s flagship “state” school. Those types of institutions have different missions, no?

They’re not mutually exclusive. There’s great value in us honoring our HBCU legacy—we’re never not going to be an HBCU—but it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t aspire to be a national leader in higher education. It’s so important to focus on quality. When you say, “Hey, who are the best urban public institutions in America?,” I want us to be in there.

But DC has gotten whiter and wealthier. If the goal is to be the flagship school of DC, presumably it would serve a different demographic than an HBCU.

Yeah, I am not unaware of the data and the trends. But I want UDC to be the type of institution that any District resident would at least consider. If you look at our mission, it has language about serving the needs of the District’s residents—but it says nothing about which residents. That’s why we focus on quality. No one will run away from a high-quality institution.

This article appears in the February 2025 issue of Washingtonian.