In the darkened sitting room of her 18-room Georgetown house, Sally Quinn—journalist, famed Washington hostess, and widow of longtime Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee—recently read a poem aloud. It was by Raymond Carver, and its final lines expressed what she wants most from her life: “To call myself beloved, to feel myself / beloved on the earth.” Quinn felt beloved in her marriage to Bradlee, and she misses that. Their love, she believes, had a spiritual quality. “Certainly, love is divine,” she told me. “Sex is divine. I mean, whoever invented it—whether it was God or whoever else—did a good job.”

At age 83, Quinn has written a new novel on this subject: Silent Retreat, which is half romance, half theological meditation. It follows a journalist who, fleeing her foundering marriage, decamps to a monastery and meets the Archbishop of Dublin. The two become engaged in an intense sexual and emotional relationship, despite his vowed celibacy and the fact that neither is permitted to speak. Quinn’s novel addresses big questions of faith and meaning, but it’s also a lot of fun. (“If anyone said it was boring, I’d go kill myself,” she said.) We spoke in April, sitting on her couch, surrounded by shelves upon shelves of books—her and Bradlee’s combined libraries from the ’70s. Her house manager served tea and gougères.

How did you come to write this book?

I belong to this group called PathNorth—they do these excursions—and about 15 years ago, they decided to go to a silent retreat at this monastery on the Shenandoah River. I thought, what the hell. I’d never spent much time alone. And it was the most amazing experience I’d ever had.

At that point, my husband was still alive, and he had dementia. So I was going through a crisis. But I hadn’t really had time to think about what was going on with me because I’d been taking care of Ben. The silence part was really important to me. I don’t get much silence in my life, and I thought it would be kind of scary, just being alone and not talking on the phone. It was a shock—the kind of shock I had the first time I ever went to a shrink. I walked out of that office just walking into walls—like, Jesus, what was that?

What felt shocking about that retreat?

Finding out who I was and who I was going to be, how I was going to get through this with Ben. It was mostly an interior monologue: How can I help Ben and how can I live my life and be who I am? It was really an identity crisis—which, by the way, has not ended. I’ve still been finding my way.

How did that experience become the subject of your novel?

My imagination got the best of me, I guess. When I was down there the first time, all the doors were open and my room was right next to the chapel and I was thinking this would be an interesting place to meet somebody. I wasn’t looking for a boyfriend, but I just thought this would be an unusual place. It evoked so many intense feelings in me, and I thought that intensity could be put onto a relationship.

So I just started working on it. I thought about it for a long time. I had masses of research and books and read everything I could about Ireland. I got into Yeats. When I finally started writing, I wrote it in six months. I wrote day and night; I was just obsessed. I couldn’t wait to get up in the morning and come down to my computer, because I wanted to know what would happen.

Was it tough to write a romance where the characters can’t speak to each other?

That’s what intrigued me in the first place—the idea that they’d have to be in silence. She had seen him on TV and he had read her stuff, so they already knew about each other, and there was that instant sexual electricity between the two of them. But they were both serious about the silence, and that’s why they’d come there: They both had a lot of issues to work out. I was thinking about what to say in promoting the book, and one thing is that this is every man’s dream: They go, they fall in love, they have sex, and they don’t talk.

Your protagonist is around 40. What do you know now that you didn’t know at her age?

I didn’t know who I was then, really. There were times when I didn’t like myself very much, when I didn’t like who I was or what I was doing. My mother was somebody everyone adored. Everybody used to say, “Oh, your mother is so nice.” And I always used to think: Nobody says that about me. So I wanted to be like my mother, but I was so self-centered. I didn’t realize that until my son, Quinn, was born when I was 40. Quinn was sick from the day he was born. We were in the hospital for the first 16 years of his life. I had to let go of my career and everything. So it was all about him and Ben, because I had to take care of Ben, too.

I don’t know whether I could go back and tell my [younger] self that you ought to start thinking about other people, but it’s the only thing that I can think of that can really make you happy—to care about other people. Buddha apparently said something about how it’s good to be selfish, because selfish people want to please themselves, and the best way to please yourself is to help other people.

What do you do lately for others?

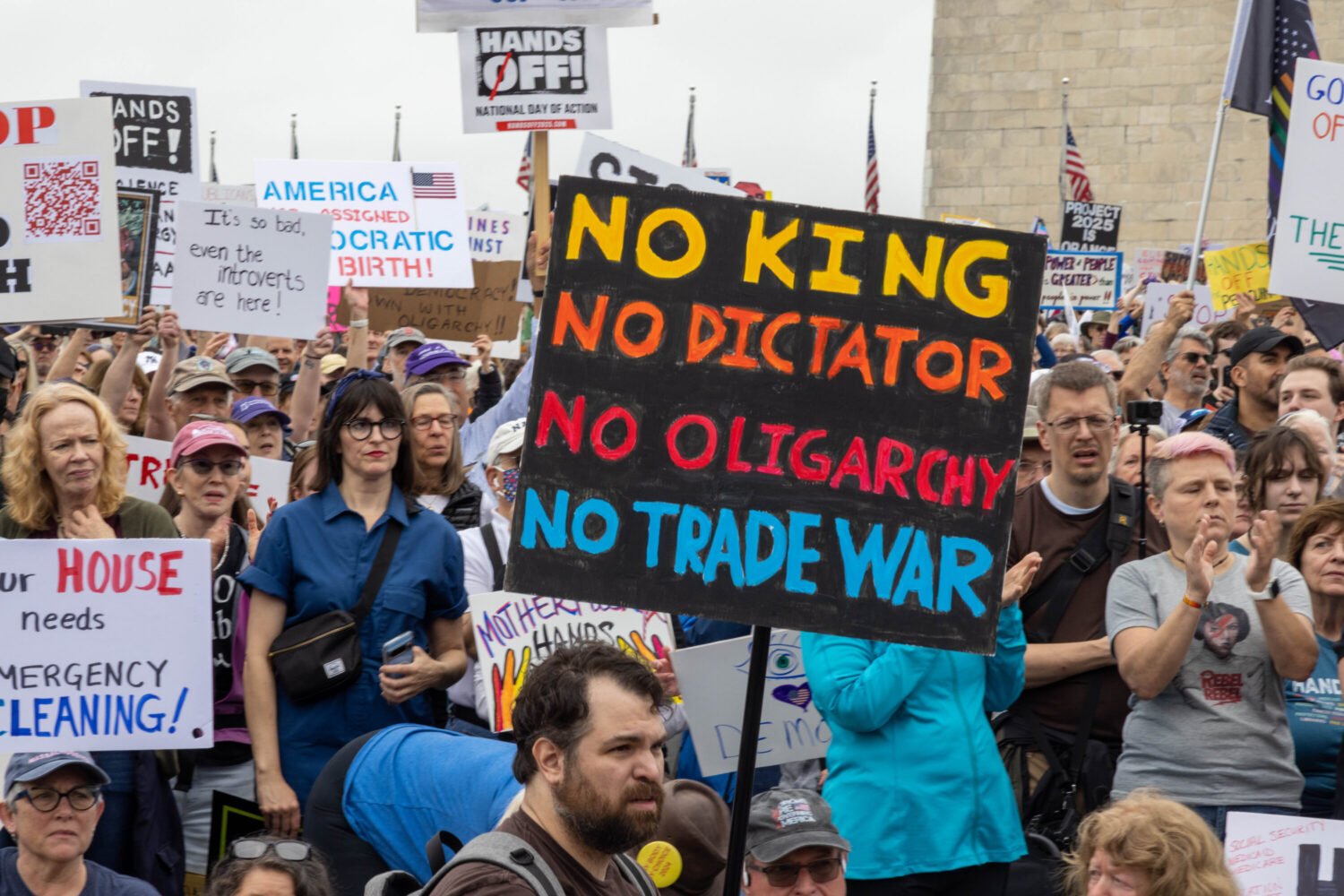

I think convening people has been helpful, having people over for dinner. A lot of conversations have been so much about politics lately, and people feel really shocked and outraged and scared and alone. It’s important to just be able to sit around the table and say those things to your friends and know that you’re not the only one thinking them. So actually, this winter I’ve been entertaining more than I ever have. For two months, I had seven parties in seven weeks. Some of them were big, too. There’s nothing I like better than having people leave my house feeling happy and good.

So you see dinner parties as having a civic function.

I do. When I first started out at the Post, I was covering parties. I’d go to these parties, and whatever news was breaking, I’d read up on it. I’d go to the national staff and the foreign staff and find out: What do you need to know? And then I’d walk into the party and there would be the Secretary of Treasury or the Secretary of Defense, and I’d go over and talk to them about it. I’d always come away having learned something.

But also, it’s hard to hate somebody if you have sat next to them at dinner and learned that their child is sick or their mother has dementia—you see that they’re real human beings. And so Ben and I always had people from both parties at our house.

Do you still?

No.

How come?

Well, because I don’t know what to talk to them about. I mean, I don’t know what to talk to the Trump people about.

Presumably, some of them have sick children.

But look what the government is doing to sick children. That’s the problem. That’s where you draw the line. People don’t share the same ethics and morals and values, and that makes it impossible. I think it’s really sad, but that’s what’s happening.

Do you follow politics closely?

Oh, yeah, I’m a total junkie.

Does that feel . . . good?

No, it feels awful.

So what do you get out of it?

It’s my duty to know what’s going on, to be informed. Because how can you be a good citizen if you’re not? I can’t do anything if I don’t know what’s going on, and I want to be able to do something and help in some way.

If you were still writing for the Style section, how would you cover this moment?

I’d go hide under the covers. No, I think I would try to do profiles.

Who would you want to profile?

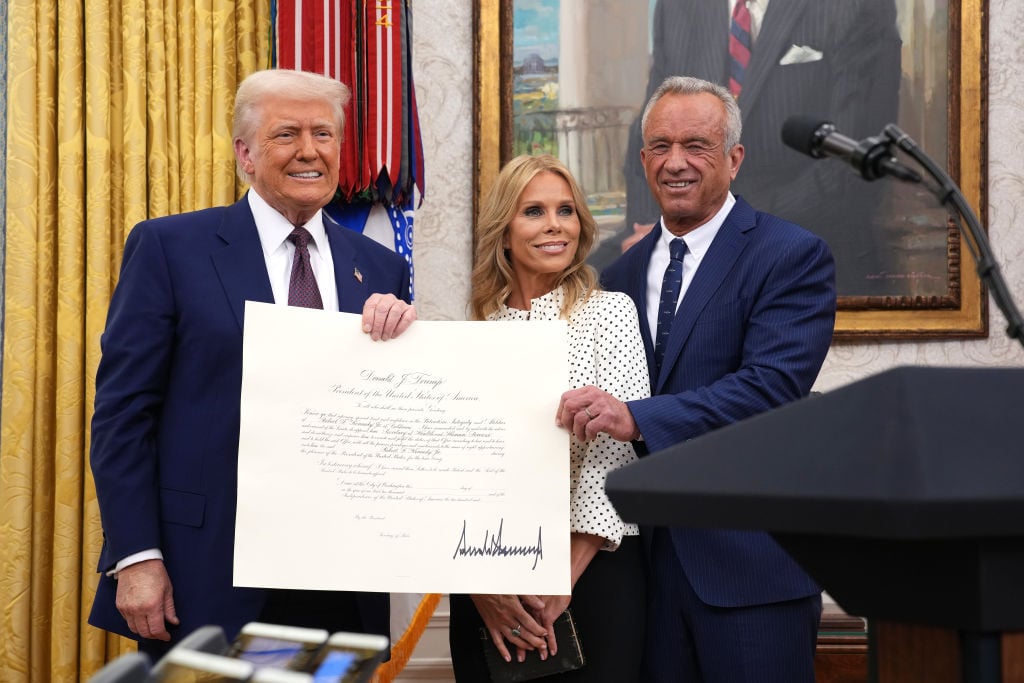

Well, not today, but I would have profiled Kimberly Guilfoyle, because she’s the prototype of everything that’s wrong. It’s all about her. It’s not about the country or what’s good for other people. She’s a symbol—the way she looks, the way she dresses, the lips, the hair, the boobs, the stilettos, the false eyelashes. I want to know what’s in the back of these people’s minds. I don’t think there’s a whole lot, actually.

Do you still subscribe to the Post?

Oh, yeah. I still subscribe. I’m still planning to write for the paper.

What’s it been like to watch all this turmoil at the Post?

It’s been like somebody died. I’ve been in a state of grief—for my country and for my newspaper. To me, the Washington Post has been sacred. It stood for everything that was good about this country—freedom of the press, the First Amendment. And I think that when people saw those values eroding, they started leaving. It’s not over yet, and I think everybody’s waiting to see who’s going to be editor of the editorial page, and then what happens with the news side. I think it would be a red line if Trump tried to kill a news story and succeeded. I think that’s what everybody’s watching for and hoping won’t happen.

Do you know Jeff Bezos?

Yes.

How?

I met him when he bought the Post. It was about a year before Ben died, and he came and spoke to the newsroom. Ben was well into dementia at that point, but he knew who Jeff was and what was going on, and he came down and listened to Jeff speak. He was impressed. Jeff did a great job that day. Everybody felt really good about him.

So I met him that day, and then I had dinner with him when they got Jason Rezaian freed [from imprisonment in Iran]. Jeff sent a plane over for him and brought him back and then had a little dinner for about 12 of us at Fiola Mare. [Bezos] was fabulous. He was funny, smart, curious, self-deprecating. He was interesting and interested in everybody. I’d see him from time to time when he’d come to Washington, and I always thought he was great.

You still do?

Well, I haven’t seen him in a long time. I just assume he’s the same person that I used to know, but I don’t know.

He’s made some controversial decisions at the Post.

Well, there are some decisions he’s made that I haven’t agreed with. But he’s always left the news side alone.

You said earlier that you’re currently experiencing an identity crisis. What’s that been like?

I’m trying to figure out where I’m going from here, what’s the next step. I’m writing a memoir right now, my Washington memoir. About a year ago, [former Post opinion columnist] Carlos Lozada said to me, “Sally, you’ve got to tell it all—you’ve got to tell everything, everything, everything.” And I said, “Well, maybe, but I’ve got to wait for a few people to die.”

Everybody thought it was so preposterous that I built this mausoleum [for Ben], but I wanted to be with him more. I meditate and I talk to him.

Do you still talk to Ben?

Ben? Yeah, all the time. There’s a mausoleum—have you seen his mausoleum? I have a little bench in there with a cushion and a fur throw and a rug and a lamp and candles and a wine opener, and I go up there and sit with him sometimes. A lot, actually. Everybody thought it was so preposterous that I built this mausoleum [in Oak Hill Cemetery], but I wanted to be with him more and I didn’t want to go and stand alone in front of the grave in the freezing cold and the rain and the heat and all that. So it’s just been wonderful to be able to go up there. I meditate and I talk to him, and that just makes me feel a lot closer to him.

What kinds of things do you talk about?

Everybody’s always asking me what Ben would think of what is going on right now, and I know what he would think. But I still talk to him about it. I’m asking him to help me figure out what I can do.

In the darkened sitting room of her 18-room Georgetown house, Sally Quinn—journalist, famed Washington hostess, and widow of longtime Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee—recently read a poem aloud. It was by Raymond Carver, and its final lines expressed what she wants most from her life: “To call myself beloved, to feel myself / beloved on the earth.” Quinn felt beloved in her marriage to Bradlee, and she misses that. Their love, she believes, had a spiritual quality. “Certainly, love is divine,” she told me. “Sex is divine. I mean, whoever invented it—whether it was God or whoever else—did a good job.”

At age 83, Quinn has written a new novel on this subject: Silent Retreat, which is half romance, half theological meditation. It follows a journalist who, fleeing her foundering marriage, decamps to a monastery and meets the Archbishop of Dublin. The two become engaged in an intense sexual and emotional relationship, despite his vowed celibacy and the fact that neither is permitted to speak. Quinn’s novel addresses big questions of faith and meaning, but it’s also a lot of fun. (“If anyone said it was boring, I’d go kill myself,” she said.) We spoke in April, sitting on her couch, surrounded by shelves upon shelves of books—her and Bradlee’s combined libraries from the ’70s. Her house manager served tea and gougères.

How did you come to write this book?

I belong to this group called PathNorth—they do these excursions—and about 15 years ago, they decided to go to a silent retreat at this monastery on the Shenandoah River. I thought, what the hell. I’d never spent much time alone. And it was the most amazing experience I’d ever had.

At that point, my husband was still alive, and he had dementia. So I was going through a crisis. But I hadn’t really had time to think about what was going on with me because I’d been taking care of Ben. The silence part was really important to me. I don’t get much silence in my life, and I thought it would be kind of scary, just being alone and not talking on the phone. It was a shock—the kind of shock I had the first time I ever went to a shrink. I walked out of that office just walking into walls—like, Jesus, what was that?

What felt shocking about that retreat?

Finding out who I was and who I was going to be, how I was going to get through this with Ben. It was mostly an interior monologue: How can I help Ben and how can I live my life and be who I am? It was really an identity crisis—which, by the way, has not ended. I’ve still been finding my way.

How did that experience become the subject of your novel?

My imagination got the best of me, I guess. When I was down there the first time, all the doors were open and my room was right next to the chapel and I was thinking this would be an interesting place to meet somebody. I wasn’t looking for a boyfriend, but I just thought this would be an unusual place. It evoked so many intense feelings in me, and I thought that intensity could be put onto a relationship.

So I just started working on it. I thought about it for a long time. I had masses of research and books and read everything I could about Ireland. I got into Yeats. When I finally started writing, I wrote it in six months. I wrote day and night; I was just obsessed. I couldn’t wait to get up in the morning and come down to my computer, because I wanted to know what would happen.

Was it tough to write a romance where the characters can’t speak to each other?

That’s what intrigued me in the first place—the idea that they’d have to be in silence. She had seen him on TV and he had read her stuff, so they already knew about each other, and there was that instant sexual electricity between the two of them. But they were both serious about the silence, and that’s why they’d come there: They both had a lot of issues to work out. I was thinking about what to say in promoting the book, and one thing is that this is every man’s dream: They go, they fall in love, they have sex, and they don’t talk.

Your protagonist is around 40. What do you know now that you didn’t know at her age?

I didn’t know who I was then, really. There were times when I didn’t like myself very much, when I didn’t like who I was or what I was doing. My mother was somebody everyone adored. Everybody used to say, “Oh, your mother is so nice.” And I always used to think: Nobody says that about me. So I wanted to be like my mother, but I was so self-centered. I didn’t realize that until my son, Quinn, was born when I was 40. Quinn was sick from the day he was born. We were in the hospital for the first 16 years of his life. I had to let go of my career and everything. So it was all about him and Ben, because I had to take care of Ben, too.

I don’t know whether I could go back and tell my [younger] self that you ought to start thinking about other people, but it’s the only thing that I can think of that can really make you happy—to care about other people. Buddha apparently said something about how it’s good to be selfish, because selfish people want to please themselves, and the best way to please yourself is to help other people.

What do you do lately for others?

I think convening people has been helpful, having people over for dinner. A lot of conversations have been so much about politics lately, and people feel really shocked and outraged and scared and alone. It’s important to just be able to sit around the table and say those things to your friends and know that you’re not the only one thinking them. So actually, this winter I’ve been entertaining more than I ever have. For two months, I had seven parties in seven weeks. Some of them were big, too. There’s nothing I like better than having people leave my house feeling happy and good.

So you see dinner parties as having a civic function.

I do. When I first started out at the Post, I was covering parties. I’d go to these parties, and whatever news was breaking, I’d read up on it. I’d go to the national staff and the foreign staff and find out: What do you need to know? And then I’d walk into the party and there would be the Secretary of Treasury or the Secretary of Defense, and I’d go over and talk to them about it. I’d always come away having learned something.

But also, it’s hard to hate somebody if you have sat next to them at dinner and learned that their child is sick or their mother has dementia—you see that they’re real human beings. And so Ben and I always had people from both parties at our house.

Do you still?

No.

How come?

Well, because I don’t know what to talk to them about. I mean, I don’t know what to talk to the Trump people about.

Presumably, some of them have sick children.

But look what the government is doing to sick children. That’s the problem. That’s where you draw the line. People don’t share the same ethics and morals and values, and that makes it impossible. I think it’s really sad, but that’s what’s happening.

Do you follow politics closely?

Oh, yeah, I’m a total junkie.

Does that feel . . . good?

No, it feels awful.

So what do you get out of it?

It’s my duty to know what’s going on, to be informed. Because how can you be a good citizen if you’re not? I can’t do anything if I don’t know what’s going on, and I want to be able to do something and help in some way.

If you were still writing for the Style section, how would you cover this moment?

I’d go hide under the covers. No, I think I would try to do profiles.

Who would you want to profile?

Well, not today, but I would have profiled Kimberly Guilfoyle, because she’s the prototype of everything that’s wrong. It’s all about her. It’s not about the country or what’s good for other people. She’s a symbol—the way she looks, the way she dresses, the lips, the hair, the boobs, the stilettos, the false eyelashes. I want to know what’s in the back of these people’s minds. I don’t think there’s a whole lot, actually.

Do you still subscribe to the Post?

Oh, yeah. I still subscribe. I’m still planning to write for the paper.

What’s it been like to watch all this turmoil at the Post?

It’s been like somebody died. I’ve been in a state of grief—for my country and for my newspaper. To me, the Washington Post has been sacred. It stood for everything that was good about this country—freedom of the press, the First Amendment. And I think that when people saw those values eroding, they started leaving. It’s not over yet, and I think everybody’s waiting to see who’s going to be editor of the editorial page, and then what happens with the news side. I think it would be a red line if Trump tried to kill a news story and succeeded. I think that’s what everybody’s watching for and hoping won’t happen.

Do you know Jeff Bezos?

Yes.

How?

I met him when he bought the Post. It was about a year before Ben died, and he came and spoke to the newsroom. Ben was well into dementia at that point, but he knew who Jeff was and what was going on, and he came down and listened to Jeff speak. He was impressed. Jeff did a great job that day. Everybody felt really good about him.

So I met him that day, and then I had dinner with him when they got Jason Rezaian freed [from imprisonment in Iran]. Jeff sent a plane over for him and brought him back and then had a little dinner for about 12 of us at Fiola Mare. [Bezos] was fabulous. He was funny, smart, curious, self-deprecating. He was interesting and interested in everybody. I’d see him from time to time when he’d come to Washington, and I always thought he was great.

You still do?

Well, I haven’t seen him in a long time. I just assume he’s the same person that I used to know, but I don’t know.

He’s made some controversial decisions at the Post.

Well, there are some decisions he’s made that I haven’t agreed with. But he’s always left the news side alone.

You said earlier that you’re currently experiencing an identity crisis. What’s that been like?

I’m trying to figure out where I’m going from here, what’s the next step. I’m writing a memoir right now, my Washington memoir. About a year ago, [former Post book critic] Carlos Lozada said to me, “Sally, you’ve got to tell it all—you’ve got to tell everything, everything, everything.” And I said, “Well, maybe, but I’ve got to wait for a few people to die.”

Everybody thought it was so preposterous that I built this mausoleum [for Ben], but I wanted to be with him more. I meditate and I talk to him.

Do you still talk to Ben?

Ben? Yeah, all the time. There’s a mausoleum—have you seen his mausoleum? I have a little bench in there with a cushion and a fur throw and a rug and a lamp and candles and a wine opener, and I go up there and sit with him sometimes. A lot, actually. Everybody thought it was so preposterous that I built this mausoleum [in Oak Hill Cemetery], but I wanted to be with him more and I didn’t want to go and stand alone in front of the grave in the freezing cold and the rain and the heat and all that. So it’s just been wonderful to be able to go up there. I meditate and I talk to him, and that just makes me feel a lot closer to him.

What kinds of things do you talk about?

Everybody’s always asking me what Ben would think of what is going on right now, and I know what he would think. But I still talk to him about it. I’m asking him to help me figure out what I can do.

This article appears in the June 2025 issue of Washingtonian.

Correction: A previous version misstated Carlos Lozada’s former job at the Washington Post.