At the beginning of September, I found myself on the back-acreage of a magnificent church—among oak trees and shrines and grottoes and birds—completely alone with my thoughts. The Franciscan Monastery of the Holy Land in America is home to a busy hive of Catholic friars, but I never met them. I was there spending 46 hours as a hermit, a person living in solitude, contemplating the mysteries of God.

I am not a religious person. I don’t pray. I’d come to this hilltop in Brookland not to grow closer to my faith, but to myself—to hear myself think, to be alone inside my own mind. I currently share a 1,000-square-foot apartment with an adult man, our chatty son, and a half-blind elderly dog. Everywhere is clanging pans and dinging phones. The dog whines, my son makes odd Darth Vader noises from the kitchen. There are only three rooms, and not one of them is properly mine; there’s nowhere I can go and shut the door.

When I’m reasonably well, I can spend limitless time on my own. But these days, my mind is not the kind of room I want to dwell in; no interesting thought has crossed its threshold in months. Instead, in rare contemplative moments, I feel dread. My mortgage is burdensome, my marriage strained. I have a chaotic extended family, many of whom seem poised to fall off the face of the Earth. The bills don’t stop coming and neither do the emails from my son’s school. It’s shredding my consciousness. I’m scattered and fatigued.

In response, my screen time has ballooned. There I am, night after night, Googling things I’m not curious about, scrolling various feeds, hoping something stimulating will appear. I’ve tried to fix it—with therapy, sobriety, exercise, Klonopin. Microdosing psychedelics. Burying myself in work. But intuitively, I figured I just needed some time alone. In solitude, I could offer myself up to the rapacious birds of my thoughts, and maybe, once picked clean, I’d have some peace.

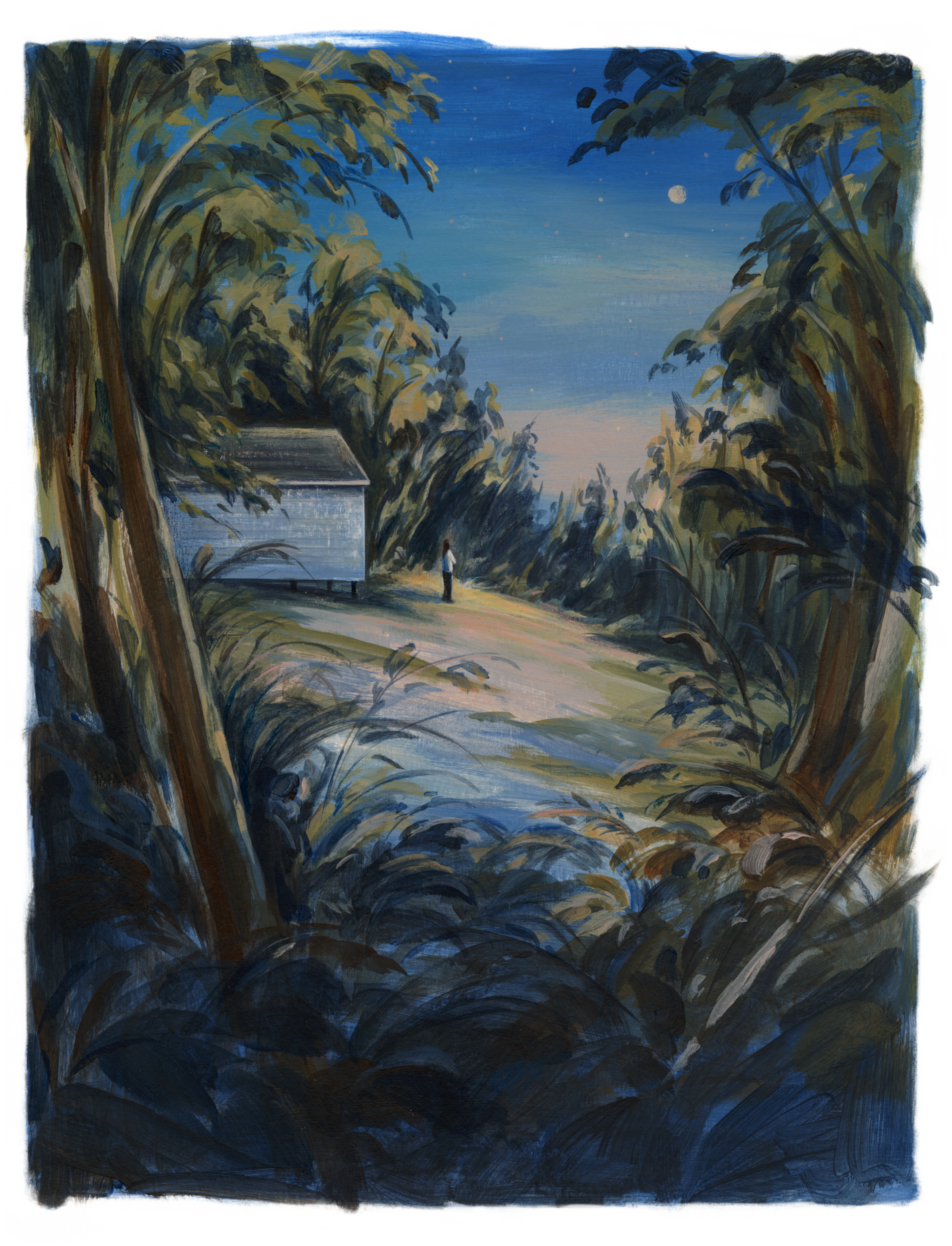

Hence the hermitage: a 350-square-foot cottage overlooking a hillside behind the church, open to the quiet-seeking public for $120 a night. I walked there from the Brookland Metro, passed through a gate, and suddenly all was bucolic: a small cemetery of white marble crosses, manicured gardens, outbuildings with peeling paint. Inside, the hermitage felt austere—a bed and a desk atop blond-hardwood floors, big windows that looked out onto the woods. The church did not provide internet. It was my choice to turn off my phone.

Those initial moments felt strange, unsettled. In a rocking chair on the porch, I forced myself to be present—to notice the breeze heaving through the stands of spindly maples, which sounded like snow on the television, like a faucet running in another room. But I struggled to sit still. Within hours, I was constructing to-do lists (things to Google, people to call), then inventing errands I could run—my idle brain creating stimulus in the form of chores.

I roved the grounds for hours, preoccupied with the state of my life. My existence is strewn with gifts: laughing with my son, the sunrise gleaming through the houseplants. But without a noticing mind, I don’t feel present to receive them.

And wasn’t this, the slog of daily life, exactly what I’d come to escape? Explicitly, yes; I wanted distance—from my family, from work, from the cascade of relentless demands—but beneath that, I was scared. Perhaps that’s why, at 5:28 pm on that first afternoon, I felt a pressing compulsion to text—not even to converse, just to hurl a few missives into the atmosphere, to jostle the people I love, to insert myself into the stream of their lives.

In my notebook, I tried to make sense of that feeling. “It’s a type of loneliness,” I wrote, “not hunger for social interaction, but for the safety and comfort of being woven into the world.” I was afraid to step outside the rhythms of my family—that not being needed, I might cease, in some odd way, to exist.

My hermit experiment seemed precarious, given the ease with which I could turn on my phone. So I decided to clarify some goals. In my notebook, I recorded them: “To be free of technology. To sit with myself. To deepen my attention and attend to sensory experience. To push through fear and discomfort and boredom. To notice things. To orient myself back towards ecstatic experiences of the world.”

For a few months when I was 18, I slept in a tent on the lawn of a stranger, an Egyptian man who’d made money on Wall Street, then moved to a hillside in LA. I’d found him online, in a database of organic gardeners. He needed help with the permaculture farm in his yard. I didn’t go to have an enraptured experience of solitude; I was underemployed and on an indefinite hiatus from college, so it seemed like a reasonable idea.

I flew to California without a laptop. My phone, the prepaid kind that charged ten cents per text, sat idle at the bottom of my bag. I had some friends, I saw them sometimes, but mostly I read books from the library and wandered the streets by myself. It never felt lonely, moving silently alongside other lives: the owner of the cluttered used-book store watching John Wayne movies behind stacks of dusty novels. The boy in the cheap arcade thumbing the mouths of machines for coins while his dad shot aliens in the dark.

I noticed things in LA. Devoid of the usual input—the chatter, the feeds—the farm was like a juice fast for my brain. My mind clarified, refocused. The ordinary texture of the world seemed to glow. In a marbled composition book, I described whatever felt meaningful: the shape of the terracotta tiles on the roof next door (little arches, dried in antiquity on Italian women’s legs), the way the lemons in the orchard gleamed pale at dusk, and the puffed neck of a particularly fat pigeon, which rippled like a bare thigh as it walked.

For those months, perception felt alchemical—the world slipped into me, as through a prism, and refracted into ideas, which all seemed connected and alive. “Having a noticing relationship to things” is a phrase I use to describe that quality of attention—of being awake to sensory experience, of finding a sacredness in the world by which everything radiates meaning. It’s secular but numinous, a little like proximity to God.

There’s a Richard Wilbur poem about this—about seeing laundry on a line, furling and billowing in the wind, and mistaking it for angels. Or not mistaking it, exactly; to the poem’s speaker, the angels are literally there, the morning air “awash” with them. It’s a poem about how the divine infuses the ordinary, even when we can’t see it. In the end, the linen has been pulled from the line and placed onto the backs of thieves, invisible traces of God mingled in the workaday world.

A small-town poetry professor in Nabokov’s Pale Fire makes a similar point in inverted terms. He declares, essentially, that he’d skip the afterlife unless various quotidian things—the marks snails leave on flagstones, “the claret taillight of that dwindling plane”—are found there. I’m moved by that notion: that the world, not heaven, is what’s sacred. That whatever the rewards of eternal life, they couldn’t possibly compare to the beauty of an airplane taillight as it descends towards the earth.

I used to experience my life that way—as ecstatic and brimming: angels in the laundry, the claret taillights of dwindling planes—but not lately. This feeling has dimmed. The leakage of the world’s radiance corresponds to my diminished time alone, and also to my phone—its frictionless glide into oblivion, into games and apps and the infinite scroll. A friend once described this as “the infosphere polluting the psychosphere.” In LA, my psychosphere was crystalline, pristine. Now it’s sludgy and dank.

At the hermitage, I hoped to recapture the noticing. It didn’t immediately come. That first night, I sat on the porch for probably an hour, watching the moon amble across the sky, clutching a mug of tea to my stomach, entertaining miscellaneous thoughts—about my brother’s illness, the man smoking behind the church in a cone of fluorescent light, the craggy stone paths behind my high school, a friend I hadn’t talked to in years. With sudden violence, a tree branch fell, cracking and crashing to the ground. I felt neither bored nor engaged.

On the porch the next morning, I opened a notebook from 2013, the fall I went back to college after some bleak years of drifting around. There are class notes, architectural drawings, then a short list of personal goals. First, to use the internet only when unavoidable. Second, no texting unless I actually have something to say. They’re so persistent, these twinned anxieties: lacking solitude and using too much tech.

Throughout the morning, I moved the rocker desperately around the porch, chased into slivers of shade, perusing that notebook. Mingled between to-do lists and study schedules, I’d written extensively about solitude; after years of self-estrangement, of drinking my way through grim jobs, I thought it would heal my brain. “Respect for myself comes from spending time alone and becoming deeply engaged with my own mind,” I wrote. Or: “This week, I’m not interested in performing my personality for acquaintances. I want to be by myself.”

Back then, I described my brain as a “half-dead lump of fat-congealed matter that mostly lies inert.” I feel that now, too. My attention lurches and frays, pulled between dough-crusted spoons in the sink, the dog vomiting on the rug, the millionth fight about homework, a backpack spilling onto the floor. Atop that unremarkable grind is a smog of baroque familial crises, whose contours would be unkind to publicly describe. But the combination has left me saturated, closed off to people and things. Every stimulus—my son requesting a carrot, a call for volunteers at his school—has come to feel like an assault. I’ve become fortified against strife, but also walled off from joy.

My second day at the hermitage, I roved the grounds for hours, preoccupied with the state of my life—how I don’t recognize the person I am at home (sullen, distracted), but because of my responsibilities, I can’t step away to quiet my mind. My existence is strewn with gifts: laughing with my son, the sunrise gleaming through the houseplants. But without a noticing mind, I don’t feel present to receive them. My life radiates—I recognize that it does—but I seem to be locked out of its warmth.

That new Miranda July book, All Fours, is basically about a hermitage. The narrator receives a surprise check for 20 grand, plans a vacation from her family, blows the money redecorating a motel room to her precise and whimsical specifications, then holes up there for weeks. She didn’t feel right within her life, so she created another one—solitary and idiosyncratic, unencumbered by the domestic script. At her hermit motel, she allows herself to sink into her desires, and one of them is to return to her child, to be back inside their shared life. Her family is meaningful. Existing within it makes her less herself.

By early evening, I’d whipped myself into a frenzy over this dilemma, so anxious that I almost took a pill. But pharmaceutical calm seemed at odds with my hermit aspirations, an off-ramp from my unruliest thoughts. Instead, I went for a run. I passed through the church gardens—palms, rosebushes, winding flagstone paths—and into the neighborhood with its fig trees and wraparound porches, shady yards that tumble into ravines.

For half an hour, I ran loops around the streets, struggling up and down hills that undulated every couple of blocks. There were chattering crows. Tall oaks. The gold sunset lying thick and then wearily across lawns. A child’s poem taped to a daycare door (“Pour on lotion, rub it in / Perfect for my summer skin”). Rails strung with lanterns. Fire pits and patio chairs. A fenced park with an angel statue, stark and white in the dusk.

Somehow, I got lost. Without a phone, I trawled the neighborhood for anything familiar. It was the commuting hour: People walked dogs, watered small patches of lawn, and pushed strollers while toddlers ran madly ahead. It was jarring, actually, how beautiful this felt—people enmeshed in their days, sweating through poly-blend suits while lugging a briefcase up their front steps.

All these lives, I understood, were mirrors of my own. These were people raising their families, negotiating schedules and hardships and griefs. From the inside, it’s relentless. Was it false to find it gorgeous from afar? Does the radiance appear only from a distance? What, in each day of my life, was I failing to see?

The next morning—my last—I brought a cup of green tea to the orchard, tracing a cracked path, ramshackle and overgrown, through the dark valley behind the church. As I walked, my reentry loomed. It seemed remarkable, all the things I wasn’t curious about: Instagram, news, email, Slack. Those leeches on my attention, devouring my waking life. What I actually wondered was what my family was up to, what my friends were thinking about, and how my sister’s camping trip had gone. It’s irrepressible, this theme in my life: the need for intimacy, the need for solitude, and the perpetual conflict between them.

I didn’t actually want to be a hermit, to abandon my obligations and leave all of that behind. I wanted to be open to my life, not protected from it. I wanted to feel immersed.

In my old notebooks, the richest parts are about people: things that happened to friends, new thoughts they enabled me to think, provocations that settled into me like a toothache, bothering me, while I played with them for days with my tongue. Constantly, people say vulnerable, revelatory things. I didn’t actually want to be a hermit, to abandon my obligations and leave all of that behind. I wanted to be open to my life, not protected from it. I wanted to feel immersed.

At the hermitage, I had not fallen back in love with the world. I’d hardly even seen it; I’d been ruminating more than noticing, indulging this tedious fixation on the state of my brain. “Letting my mind spin in isolation is only good when the fodder is good,” I’d written the night before. “But if you’re living well, the fodder is always good. Life is always sufficiently rich.” I had not been living well, and the hermitage—a single dose of concentrated isolation—couldn’t fix it. “It’s like tuning an antenna,” I wrote in my notes. “If I’m not regularly by myself, the reception grows poor, and the pathos of things floats into the atmosphere, unremarked.”

But by that last morning, I’d been tuning for days. I’d grown bored with my neuroses. I’d exhausted myself. There was a moment, walking to the orchard, when I felt my eyeballs turn outwards and my mind unclench. Out in the field by the orchard, a hawk flapped across the sky and tucked itself into an evergreen tree. A tendril of black landscaping fabric rose from the ground like a snake. I gulped the air. The tang of grass hit my throat, vegetal and earthy. Everywhere, the consecrating light.

Towards the rising sun, grapes grew over a chain-link fence, sheer fabric draped around them, protecting them from pests. The sunrise swept long, angular shadows onto the grass. And then it happened—I felt astonished, pierced. Here, like in the laundry poem, was an angel: White fabric hung over cascading bundles of grapes, lit and shining, as if the fruit were luminescent itself.

Describing it seems to demand a religious vocabulary: “sacred,” “ecstatic,” “miracle,” “grace.” But really, I was only seeing, experiencing the world as it is.

This article appears in the December 2024 issue of Washingtonian.