The dress code is black tie or bathing suit. As guests arrive at the three-story rowhouse in Truxton Circle, they tie masquerade masks over their faces. Everyone’s committed to the bit—shimmery dresses, black bow ties, and one guy in a scuba suit.

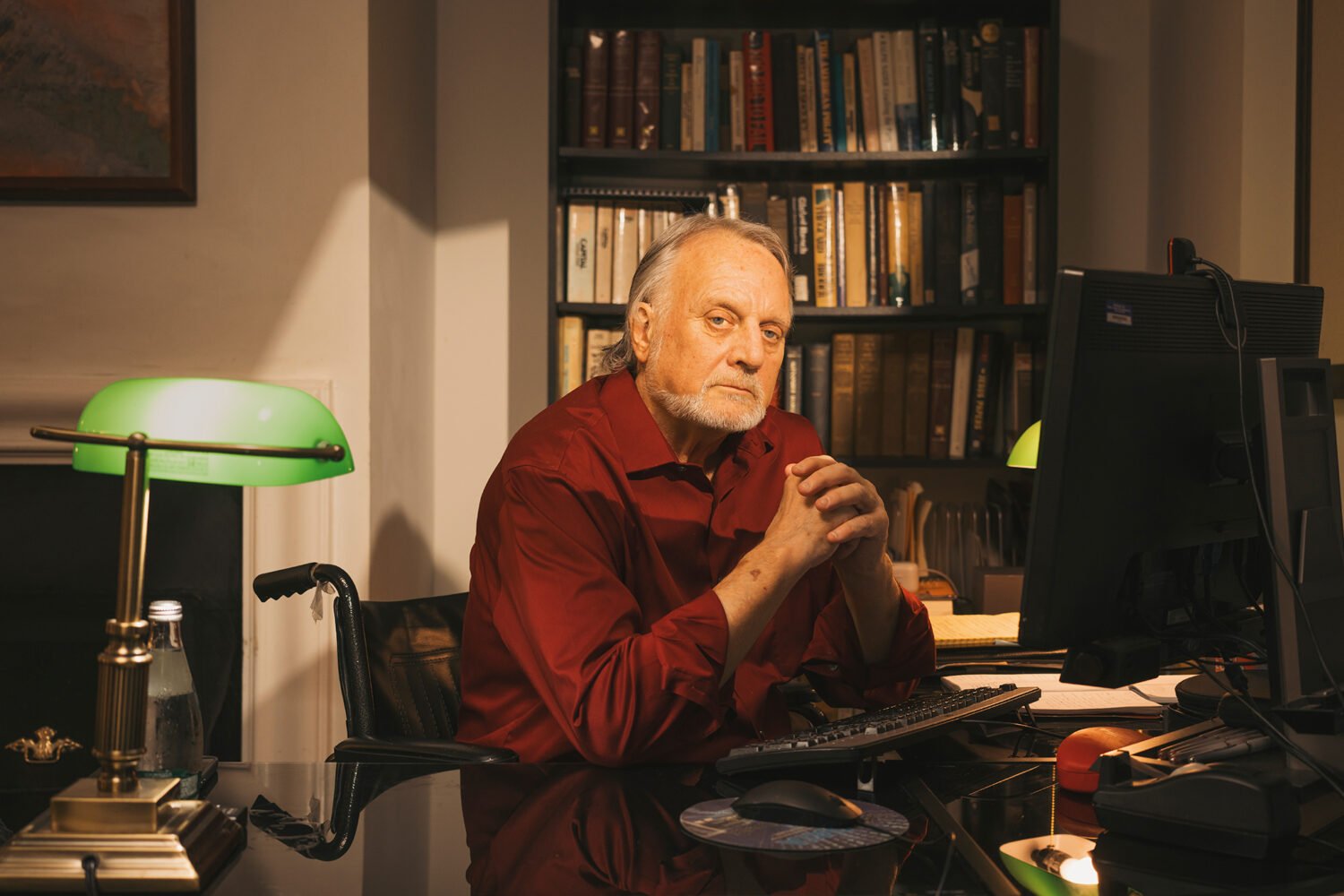

But perhaps what’s most notable about this fancy house party is the accessory people are missing: their phones. The host is Danny Hogenkamp, the 31-year-old CEO of Grassroots Analytics, a DC company specializing in fundraising software for nonprofits and Democratic campaigns. Standing six-foot-six in a velvety dark-blue suit, he greets guests and tells them where to find the batched martinis. He also hands everyone a Yondr case, a pouch that locks up your phone while still allowing you to carry it. By the front door, there’s a plexiglass phone locker with old-fashioned keys. Everyone here—from an Instagram influencer to a former congresswoman—must stow their devices.

A magician named “Sly” makes a silver dollar disappear and reappear, and a DJ blasts beats next to the charcuterie spread. Eyes Wide Shut is playing on a TV. Hogenkamp eventually swaps his blue suit for a red swimsuit, then sprints onto the freezing patio and into a hot tub, where a small group gathers to drink Kirkland hard seltzers. At a certain point, I realize I have no idea how many hours have passed, so I check the time on the one place I can find it—the thermostat. Only later do I realize it was an hour off.

The party is—dare I say?—incredibly fun. And for Hogenkamp, that’s the first step of a grander plan. He may be a young tech guy, but he’s also a self-described “Luddite” with a flip phone—used for texts and calls, that’s it—and no social media. And he’s on a mission to get others to unplug more, too.

“I’m out on a limb here, right? A lot of people think I’m crazy,” he says. And yet, “all of science is on my side.”

In recent years, Hogenkamp has hosted a series of phone-free events at bars and briefly flirted with the idea of his own offline bar. He oversees the local chapter of a nonprofit called the Luddite Club. He’s advocated for legislation aimed at curbing the next generation’s social-media addictions–but has since become skeptical. “I have found politicians and journalists the worst phone addicts,” he says. “It’s like asking junkies to solve the drug crisis. No offense.”

Still, Hogenkamp’s cause has never felt more resonant. You don’t need to read the mountain of studies to know that social media is destroying our attention spans, making us insecure about our bodies, and sucking us into a cesspool of misinformation and hate. And increasingly, our troubles with tech aren’t just personal—they’re political. Consider the national-security debate around TikTok, the legal and ethical battles over AI, X owner Elon Musk’s misadventures in government, and the rise of a “tech oligarchy” tweaking our algorithms in new and precarious ways. Whose relationship with their phone isn’t fraught?

“We’re at the beginning of something,” Hogenkamp says of the budding offline movement. “We’ve got something by the tail, and it’s just not clear if it’s a wombat or an elephant.”

“I Feel Like a Superperson”

I first met Hogenkamp after he emailed to complain about one of my stories. New York restaurateur Keith McNally had just opened his buzzy Minetta Tavern and its luxurious upstairs Lucy Mercer Bar in Union Market, and I had written about the latter implementing a no-phone policy. So Hogenkamp and a few “hopeful Luddites” eagerly visited before the holidays

They found that almost everyone was on their phones. “It was so clear, so immediately, that no one there cared at all about this thing,” Hogenkamp says. “It was like a crazy dystopian universe.”

Afterward, Hogenkamp called, emailed, and mailed the restaurant multiple times, offering McNally a substantial financial investment so he could use Yondr cases to actually enforce the policy. The outreach never went anywhere, even after I introduced the two over email. McNally subsequently admitted to me “we don’t enforce the rule as much as we should” but said he planned to crack down soon. A few months later, McNally shared a photo of the martini-strewn bar. “Note the absence of iPhones,” he wrote—from his phone to his 142,000 followers on Instagram.

In some ways, Hogenkamp is an unlikely advocate for unplugged living. Growing up in rural Vermont, where his parents were small-town doctors, he got an iPhone in high school and quickly became addicted to social media, like pretty much every other teen. As a student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, he regularly tweeted about politics and college basketball. And he and his now-wife started dating in college the old-fashioned way—stalking each other on Facebook.

Hogenkamp’s company was born of a post-graduation gig trying to elect a Democratic House candidate in upstate New York. He helped develop analytics software to bring in more low-dollar donations. Hogenkamp’s candidate lost, but his donor-matching algorithm was a winner. He founded Grassroots Analytics in 2017, building it into a 62-employee company that’s worked with campaigns for Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, John Fetterman, Kamala Harris, and others.

“Modern friendship for most people our age is we go and sit places and look at our phones and then every two minutes one of us will say something. It’s crazy.”

Part of Hogenkamp’s eventual rejection of his smartphone was professional: He started some device-free meetings in 2021 when his team returned to the office from the pandemic, and found the powwows far more productive and creative. At the same time, he was taking stock of the phone use in his personal life. “Modern friendship for most people our age is, like, we go and sit places and look at our phones and then every two minutes one of us will say something,” Hogenkamp says. “It’s crazy.”

Hogenkamp was also getting into fights about UNC basketball on Twitter, making mean and belittling comments about the team’s coach. “I lost some friends,” he says. “I think I came across so angry and ill-intentioned online.” Social media, he realized, was not the healthiest space for someone so unfiltered.

Going offline happened in fits and starts. Hogenkamp deleted Twitter but was still using it on his computer browser, so he started using a VPN to block the site altogether. Meanwhile, he turned his phone screen black and white, a trick that’s supposed to make it less appealing to look at. Finally, a friend bought him a flip phone, or “dumb phone,” as a joke. Hogenkamp never went back. (Fittingly for DC, the last thing he blocked was LinkedIn, though his staff now manages it.)

Hogenkamp isn’t anti-tech: He runs a tech company. He still has a computer, and I can personally confirm he’s very prompt with emails. If he needs directions, he looks them up on his desktop first. If he needs a ride, he’ll give a friend cash to call him an Uber or hail one from his computer. And he technically still has his iPhone, which never leaves his work desk, in order to complete two-factor authentications on his bank and cryptocurrency accounts.

There are plenty of other inconveniences, such as restaurants that have switched to QR menus and airlines that charge extra for printed tickets. Particularly annoying to Hogenkamp? Washington Wizards tickets have gone digital. But “it’s all just a state of mind,” he says. “If you view every logistical hurdle as a fun, creative problem that you get to solve and a chance to interact with people and have a real human experience, it just becomes so amazing.” To wit: Hogenkamp has befriended the “Wizards season-ticket guy” to get tickets from will-call. “There’s always a workaround,” he says.

Hogenkamp describes his lifestyle as a “radical act of self-growth and self-improvement.” He went from reading 20 books a year to around 120. He writes five or six pages of notes in a journal each day. He’s become a devotee of a yoga studio in Bloomingdale and very active in a pickup basketball group. “Finding out how much time you have when you don’t use your phone is crazy,” he says. “I gained an extra seven hours in my day. I feel like a superperson.”

The Luddite Club

At first, Hogenkamp was the only one he knew with a flip phone. Then, in late 2022, he read a story in the New York Times about the Luddite Club, a group of high-school and college kids actively rejecting their generation’s addiction to smartphones and social media. It was started by Logan Lane, a Brooklyn teen who’d decided to give up her iPhone after feeling oversaturated by screen life during Covid. “Flip-phone Jesus,” Hogenkamp jokingly calls her.

He reached out to Lane and eventually encouraged her to apply for an internship at his company. Her job was cold-calling organizations that might be interested in the company’s fundraising platform. She thought she might have better luck with a personal story, so she sought out nonprofits in the “tech-resistant” space, like Wait Until 8th, which encourages parents to delay giving their kids smartphones until the end of eighth grade.

Lane quickly realized that a lot of these organizations were dominated by teachers, parents, psychologists, and other authority figures trying to limit phone use. She knew proselytizing to young people didn’t work—but inspiration and support from their peers might. Why not turn the Luddite Club into a national nonprofit that could help set up groups similar to the one she’d created in high school? Hogenkamp gave her some guidance as well as the organization’s first donation. It now has 15 to 20 clubs up and running nationwide, including a DC-area high-school chapter in its early stages and an adult chapter headed by Hogenkamp.

Meanwhile, he started hosting phone-free events at DC bars such as the Pub & the People and Never Looked Better. He also looked at locations for his own offline bar. Sans devices, Hogenkamp noticed, people were drinking a lot more, sometimes to the point of “making crazy, life-altering decisions.” Gen-Z famously drinks less than millennials, and Hogenkamp theorizes that’s only because they’re self-medicating with phones, which he calls “more spiritually soul-crushing than alcohol.” Ultimately, he gave up his bar plans—in part because he didn’t want to be constantly surrounded by the temptation of alcohol.

Instead, Hogenkamp has channeled his restlessness and charisma into essentially becoming his own IRL social network, trying to recruit friends to live in his neighborhood and hosting elaborate house parties. The most recent was a “Hippie Party” with a tie-dye station, flower-crown making, and a rooftop band.

Along the way, Hogenkamp has managed to attract or convert a cadre of like-minded Gen-Zers and young millennials, including his wife, Tali deGroot. “People like to get swept up in the Danny tornado—sometimes without even noticing it,” says deGroot, who also works in political fundraising. Though she still has a smartphone, she locks it up or leaves it at the office during evenings and weekends and switches to a dumb phone. She’s also given up social media, as have some of her friends, which she credits to Hogenkamp’s influence and “haranguing.”

“You can’t talk to him without getting an earful about it,” deGroot says. “I’m always warning people, ‘Danny’s an extremist. He’s a zealot. Be prepared. He’s not going to sugarcoat it or make it easy for you to hear. He’s just going to come for your life.’ ”

“DC Is Like Ground Zero”

One of Hogenkamp’s “flip-phone friends,” 28-year-old Grant Besner, wants to meet at Rock Creek Cemetery. We wander the graveyard for almost 20 minutes until finally finding the tombstone he’s looking for. “Emile Berliner, buried right here in front of us, is the original DC tech bro—full stop,” Besner says.

Best known as the inventor of the gramophone, Berliner also helped make Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone far more audible. Besner holds up his own phone, which looks like the kind of basic calculator a third-grader would use. “What I’m holding in my hand, [Berliner] is directly responsible for,” Besner says. He notes that a lot of today’s telecommunications and media environment has DC roots—from the first telegraph message transmitted in America to locally founded internet trailblazer AOL. “I think this is a really fitting site to think about what neo-Luddism is. DC is like ground zero for the interconnectivity of the human race.”

The original Luddites got their name from Ned Ludd, the fictional folk hero who came to represent early-19th-century English textile workers rebelling against industrialization by destroying looms and burning down factories. “I wouldn’t say, necessarily, I’m a Luddite. Because for me, it’s not about rage against the machine,” Besner says. “I want to do things with people.”

For Hogenkamp, it’s also about anti-consumerism at a time when so much of social media is about monetizing your attention. “Anything on the internet gets co-opted immediately by corporate interests to sell you doodads.”

Forgoing Amazon, Hogenkamp keeps “extravagant” lists of things he needs for trips to Costco or Target every few months. He has also limited takeout to a handful of restaurants he can walk to. But some things are inescapable. Hogenkamp’s own company relies on monetizing people’s attention, including through social media, though he tells me it’s not reliably effective outside a small number of viral moments.

By pure coincidence, Grassroots Analytics is located on the same Chinatown block where Berliner worked when he first immigrated to the US from Germany. The office feels like something out of Silicon Valley, with putt-putt golf, a piano, and a high-tech water dispenser that adds electrolytes. Hogenkamp—looking very much the part of a young founder, with tousled brown hair and a gray sweatshirt from his alma mater—doesn’t have an office, just a standing desk with three separate monitors.

Despite his professional success, he doesn’t possess the one thing that so often signifies it in This Town: “DC is all about clout and power,” Hogenkamp says. “And there’s this one metric easily available on the internet of how important you are, which is your number of followers—and I’m at zero. So for a lot of people, it’s just like, ‘Oh, you’re not on social media? You must have zero power and influence.’ ”

Nearly a century after Berliner’s death, the District is a particularly online city. It’s all about who can respond to an email the fastest and who can send the breaking-news tweet to the group chat first. It’s how many followers you have—and who’s following you. It’s memes and influencers. It’s a place where culture and politics are shaped by social media, from Black Lives Matter to Brat. Which begs the question: How do you get attention for a social movement when you’re rejecting the entire attention machine?

“There are all these awesome little bubbles of flip-phone people popping up in cities and towns all across America and worldwide,” Hogenkamp says. “But they don’t know about each other and can’t connect. We’re purposely hard to get in touch with.”

“You Still Have to Make It a Little Palatable”

To help people unplug, Hogenkamp has a million ideas, big and small. He’d like to see tech detox centers—think White Lotus–style phone rehab. He’s tried developing tech that helps people be anti-tech, including an app allowing them to bet with friends on who uses less screen time and to reward kids with allowance for limiting their online usage. He also talks about buying an abandoned property next door to his house to open a sauna and steam room. “Obviously, no phones there,” he says. “It’s just inhospitable to electronics.”

As much as Hogenkamp wants to create offline spaces that are accessible to all, most of those that exist already tend to be luxury experiences, whether super-high-end restaurants or resorts. “A lot of celebrities are increasingly gravitating to the no-phone thing,” he says. “I think it might become kind of a status symbol of the elite.” Just look at what Hogenkamp calls the “flip-phone Mount Rushmore”: actor Michael Cera, director Christopher Nolan, and pop star Rihanna—though she has been spotted recently with an iPhone. (In Washington, Democratic senator Chuck Schumer famously uses a flip phone.) Of course, if you’re rich and famous, you probably have an assistant with a smartphone. Hogenkamp does.

Can the smartphone-free lifestyle work for everyone else? Besner and a couple others recently started piloting what he says is an “experimental incubator for the offline-curious,” called Month Offline. Small cohorts rent flip phones for a month, supporting one another with meetups. “One of the hardest things when you get into this is you feel isolated,” Besner says. There’s an element of reflection—“kind of like an AA group for phone addicts”—but also fun weekly get-togethers and challenges, like taking photos with a disposable film camera to see what people capture when they don’t have unlimited shots. Fittingly, the group doesn’t have a website, just a number: 844-OFFLINE.

Meanwhile, Rock Harper, the DC chef of Hell’s Kitchen fame, recently launched regular phone-free nights at his H Street bar, Hill Prince, where he’ll host DJ sets, comedy shows, book clubs, dining experiences, and other very IRL activities. He’s also toying with other ideas—maybe you get happy-hour deals all night if you agree to go phone-free, or phones are restricted everywhere but the patio, like a smoking section.

“I grew up in the club, where if you wanted a girl’s number, you had to try to find a pen and a piece of paper or memorize a number,” Harper says. “My question right now is: How can I help us remember—or introduce to some of the younger folks who haven’t had it—the power of being present?”

Harper is strongly considering creating a fully present, fully offline bar at Hill Prince or elsewhere, but he’s not sure everyone else is there yet. “It’s just like with cuisine, right?” he says. “As a chef, when you introduce something new or kind of innovative or novel, you can’t just do it. Even the best chefs that have the most captive audiences, you still have to make it a little palatable. If I just say, ‘No phones this week,’ you’re going to piss a lot of people off.”

“People Have Started to Understand”

In February, the New York Times published a follow-up article about the Luddite Club. The response was overwhelming. “We got, like, 50 emails every single day,” says Lane, the club’s founder. “A lot of people wanted to start Luddite Clubs for, like, weeks and weeks and weeks. We raised $10,000 doing nothing.” DC’s very informal adult chapter received about a dozen inquiries.

Policy changes are also brewing. Last summer, then–surgeon general Vivek Murthy called for social-media platforms to come with warning labels, like packs of cigarettes. He noted that young people who spend more than three hours a day on social media double their risk of anxiety and depression. A bipartisan group of senators has proposed legislation that would ban those under 13 from social media. Similar efforts to prohibit phones in schools—a goal supported by current Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.—have been gaining traction nationwide, including in Virginia, which began making the move for K–12 students this year.

Lane believes a broader cultural shift is underway and that hundreds of thousands—if not millions—of people in America don’t like the state of their tech use and want to make a change. “Four years ago, I got rid of my smartphone and literally everyone in my life was like, ‘What are you doing? That’s so weird,’ ” Lane says. “The past couple of years, people have started to understand. It does feel like things are really coming to a head.”

Recently, I started noting the way people in my life talked about their phone use. Nobody seemed happy—including me. I thought about the conflicting relief and shame I feel as a mom bribing my kids with their screens so I can look at mine. Or the way I beat myself up for wasting so much time on Instagram while simultaneously feeling I should be on Instagram more to build my following and “brand.” Yes, social media is important to my work—but if I’m being honest, not to the extent that I use it.

So one weekend, I deleted all the social-media apps from my phone: X, Instagram, Threads, Bluesky, Facebook, TikTok. (Hogenkamp is right: Journalists are the worst addicts.) There was something liberating about it, like setting an away message for vacation and knowing nobody will bother you. I felt a slight air of superiority, too—I’d broken free! But in quiet moments throughout the day—sitting on the Metro, waiting for dinner in the oven—the panic and discomfort of boredom bubbled up. I resorted to other distractions, like reading the news or a book

Then it was Monday. I re-downloaded most of my apps and returned to my mindless scrolling. Still, there have been a few small victories. I haven’t gone back to TikTok, which for me was the most time-sucking platform, and I try to be more mindful of how much I need to be plugged in for work—and the lies I tell myself to the contrary. It feels like I have something by the tail. Wombat or elephant? Like Hogenkamp, I’m not sure yet.

The dress code is black tie or bathing suit. As guests arrive at the three-story rowhouse in Truxton Circle, they tie masquerade masks over their faces. Everyone’s committed to the bit—shimmery dresses, black bow ties, and one guy in a scuba suit.

But perhaps what’s most notable about this fancy house party is the accessory people are missing: their phones. The host is Danny Hogenkamp, the 31-year-old CEO of Grassroots Analytics, a DC company specializing in fundraising software for nonprofits and Democratic campaigns. Standing six-foot-six in a velvety dark-blue suit, he greets guests and tells them where to find the batched martinis. He also hands everyone a Yondr case, a pouch that locks up your phone while still allowing you to carry it. By the front door, there’s a plexiglass phone locker with old-fashioned keys. Everyone here—from an Instagram influencer to a former congresswoman—must stow their devices.

A magician named “Sly” makes a silver dollar disappear and reappear, and a DJ blasts beats next to the charcuterie spread. Eyes Wide Shut is playing on a TV. Hogenkamp eventually swaps his blue suit for a red swimsuit, then sprints onto the freezing patio and into a hot tub, where a small group gathers to drink Kirkland hard seltzers. At a certain point, I realize I have no idea how many hours have passed, so I check the time on the one place I can find it—the thermostat. Only later do I realize it was an hour off.

The party is—dare I say?—incredibly fun. And for Hogenkamp, that’s the first step of a grander plan. He may be a young tech guy, but he’s also a self-described “Luddite” with a flip phone—used for texts and calls, that’s it—and no social media. And he’s on a mission to get others to unplug more, too.

“I’m out on a limb here, right? A lot of people think I’m crazy,” he says. And yet, “all of science is on my side.”

In recent years, Hogenkamp has hosted a series of phone-free events at bars and briefly flirted with the idea of his own offline bar. He oversees the local chapter of a nonprofit called the Luddite Club. He’s advocated for legislation aimed at curbing the next generation’s social-media addictions–but has since become skeptical. “I have found politicians and journalists the worst phone addicts,” he says. “It’s like asking junkies to solve the drug crisis. No offense.”

Still, Hogenkamp’s cause has never felt more resonant. You don’t need to read the mountain of studies to know that social media is destroying our attention spans, making us insecure about our bodies, and sucking us into a cesspool of misinformation and hate. And increasingly, our troubles with tech aren’t just personal—they’re political. Consider the national-security debate around TikTok, the legal and ethical battles over AI, X owner Elon Musk’s misadventures in government, and the rise of a “tech oligarchy” tweaking our algorithms in new and precarious ways. Whose relationship with their phone isn’t fraught?

“We’re at the beginning of something,” Hogenkamp says of the budding offline movement. “We’ve got something by the tail, and it’s just not clear if it’s a wombat or an elephant.”

“I Feel Like a Superperson”

I first met Hogenkamp after he emailed to complain about one of my stories. New York restaurateur Keith McNally had just opened his buzzy Minetta Tavern and its luxurious upstairs Lucy Mercer Bar in Union Market, and I had written about the latter implementing a no-phone policy. So Hogenkamp and a few “hopeful Luddites” eagerly visited before the holidays

They found that almost everyone was on their phones. “It was so clear, so immediately, that no one there cared at all about this thing,” Hogenkamp says. “It was like a crazy dystopian universe.”

Afterward, Hogenkamp called, emailed, and mailed the restaurant multiple times, offering McNally a substantial financial investment so he could use Yondr cases to actually enforce the policy. The outreach never went anywhere, even after I introduced the two over email. McNally subsequently admitted to me “we don’t enforce the rule as much as we should” but said he planned to crack down soon. A few months later, McNally shared a photo of the martini-strewn bar. “Note the absence of iPhones,” he wrote—from his phone to his 142,000 followers on Instagram.

In some ways, Hogenkamp is an unlikely advocate for unplugged living. Growing up in rural Vermont, where his parents were small-town doctors, he got an iPhone in high school and quickly became addicted to social media, like pretty much every other teen. As a student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, he regularly tweeted about politics and college basketball. And he and his now-wife started dating in college the old-fashioned way—stalking each other on Facebook.

Hogenkamp’s company was born of a post-graduation gig trying to elect a Democratic House candidate in upstate New York. He helped develop analytics software to bring in more low-dollar donations. Hogenkamp’s candidate lost, but his donor-matching algorithm was a winner. He founded Grassroots Analytics in 2017, building it into a 62-employee company that’s worked with campaigns for Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, John Fetterman, Kamala Harris, and others.

“Modern friendship for most people our age is we go and sit places and look at our phones and then every two minutes one of us will say something. It’s crazy.”

Part of Hogenkamp’s eventual rejection of his smartphone was professional: He started some device-free meetings in 2021 when his team returned to the office from the pandemic, and found the powwows far more productive and creative. At the same time, he was taking stock of the phone use in his personal life. “Modern friendship for most people our age is, like, we go and sit places and look at our phones and then every two minutes one of us will say something,” Hogenkamp says. “It’s crazy.”

Hogenkamp was also getting into fights about UNC basketball on Twitter, making mean and belittling comments about the team’s coach. “I lost some friends,” he says. “I think I came across so angry and ill-intentioned online.” Social media, he realized, was not the healthiest space for someone so unfiltered.

Going offline happened in fits and starts. Hogenkamp deleted Twitter but was still using it on his computer browser, so he started using a VPN to block the site altogether. Meanwhile, he turned his phone screen black and white, a trick that’s supposed to make it less appealing to look at. Finally, a friend bought him a flip phone, or “dumb phone,” as a joke. Hogenkamp never went back. (Fittingly for DC, the last thing he blocked was LinkedIn, though his staff now manages it.)

Hogenkamp isn’t anti-tech: He runs a tech company. He still has a computer, and I can personally confirm he’s very prompt with emails. If he needs directions, he looks them up on his desktop first. If he needs a ride, he’ll give a friend cash to call him an Uber or hail one from his computer. And he technically still has his iPhone, which never leaves his work desk, in order to complete two-factor authentications on his bank and cryptocurrency accounts.

There are plenty of other inconveniences, such as restaurants that have switched to QR menus and airlines that charge extra for printed tickets. Particularly annoying to Hogenkamp? Washington Wizards tickets have gone digital. But “it’s all just a state of mind,” he says. “If you view every logistical hurdle as a fun, creative problem that you get to solve and a chance to interact with people and have a real human experience, it just becomes so amazing.” To wit: Hogenkamp has befriended the “Wizards season-ticket guy” to get tickets from will-call. “There’s always a workaround,” he says.

Hogenkamp describes his lifestyle as a “radical act of self-growth and self-improvement.” He went from reading 20 books a year to around 120. He writes five or six pages of notes in a journal each day. He’s become a devotee of a yoga studio in Bloomingdale and very active in a pickup basketball group. “Finding out how much time you have when you don’t use your phone is crazy,” he says. “I gained an extra seven hours in my day. I feel like a superperson.”

The Luddite Club

At first, Hogenkamp was the only one he knew with a flip phone. Then, in late 2022, he read a story in the New York Times about the Luddite Club, a group of high-school and college kids actively rejecting their generation’s addiction to smartphones and social media. It was started by Logan Lane, a Brooklyn teen who’d decided to give up her iPhone after feeling oversaturated by screen life during Covid. “Flip-phone Jesus,” Hogenkamp jokingly calls her.

He reached out to Lane and eventually encouraged her to apply for an internship at his company. Her job was cold-calling organizations that might be interested in the company’s fundraising platform. She thought she might have better luck with a personal story, so she sought out nonprofits in the “tech-resistant” space, like Wait Until 8th, which encourages parents to delay giving their kids smartphones until the end of eighth grade.

Lane quickly realized that a lot of these organizations were dominated by teachers, parents, psychologists, and other authority figures trying to limit phone use. She knew proselytizing to young people didn’t work—but inspiration and support from their peers might. Why not turn the Luddite Club into a national nonprofit that could help set up groups similar to the one she’d created in high school? Hogenkamp gave her some guidance as well as the organization’s first donation. It now has 15 to 20 clubs up and running nationwide, including a DC-area high-school chapter in its early stages and an adult chapter headed by Hogenkamp.

Meanwhile, he started hosting phone-free events at DC bars such as the Pub & the People and Never Looked Better. He also looked at locations for his own offline bar. Sans devices, Hogenkamp noticed, people were drinking a lot more, sometimes to the point of “making crazy, life-altering decisions.” Gen-Z famously drinks less than millennials, and Hogenkamp theorizes that’s only because they’re self-medicating with phones, which he calls “more spiritually soul-crushing than alcohol.” Ultimately, he gave up his bar plans—in part because he didn’t want to be constantly surrounded by the temptation of alcohol.

Instead, Hogenkamp has channeled his restlessness and charisma into essentially becoming his own IRL social network, trying to recruit friends to live in his neighborhood and hosting elaborate house parties. The most recent was a “Hippie Party” with a tie-dye station, flower-crown making, and a rooftop band.

Along the way, Hogenkamp has managed to attract or convert a cadre of like-minded Gen-Zers and young millennials, including his wife, Tali deGroot. “People like to get swept up in the Danny tornado—sometimes without even noticing it,” says deGroot, who also works in political fundraising. Though she still has a smartphone, she locks it up or leaves it at the office during evenings and weekends and switches to a dumb phone. She’s also given up social media, as have some of her friends, which she credits to Hogenkamp’s influence and “haranguing.”

“You can’t talk to him without getting an earful about it,” deGroot says. “I’m always warning people, ‘Danny’s an extremist. He’s a zealot. Be prepared. He’s not going to sugarcoat it or make it easy for you to hear. He’s just going to come for your life.’ ”

“DC Is Like Ground Zero”

One of Hogenkamp’s “flip-phone friends,” 28-year-old Grant Besner, wants to meet at Rock Creek Cemetery. We wander the graveyard for almost 20 minutes until finally finding the tombstone he’s looking for. “Emile Berliner, buried right here in front of us, is the original DC tech bro—full stop,” Besner says.

Best known as the inventor of the gramophone, Berliner also helped make Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone far more audible. Besner holds up his own phone, which looks like the kind of basic calculator a third-grader would use. “What I’m holding in my hand, [Berliner] is directly responsible for,” Besner says. He notes that a lot of today’s telecommunications and media environment has DC roots—from the first telegraph message transmitted in America to locally founded internet trailblazer AOL. “I think this is a really fitting site to think about what neo-Luddism is. DC is like ground zero for the interconnectivity of the human race.”

The original Luddites got their name from Ned Ludd, the fictional folk hero who came to represent early-19th-century English textile workers rebelling against industrialization by destroying looms and burning down factories. “I wouldn’t say, necessarily, I’m a Luddite. Because for me, it’s not about rage against the machine,” Besner says. “I want to do things with people.”

For Hogenkamp, it’s also about anti-consumerism at a time when so much of social media is about monetizing your attention. “Anything on the internet gets co-opted immediately by corporate interests to sell you doodads.”

Forgoing Amazon, Hogenkamp keeps “extravagant” lists of things he needs for trips to Costco or Target every few months. He has also limited takeout to a handful of restaurants he can walk to. But some things are inescapable. Hogenkamp’s own company relies on monetizing people’s attention, including through social media, though he tells me it’s not reliably effective outside a small number of viral moments.

By pure coincidence, Grassroots Analytics is located on the same Chinatown block where Berliner worked when he first immigrated to the US from Germany. The office feels like something out of Silicon Valley, with putt-putt golf, a piano, and a high-tech water dispenser that adds electrolytes. Hogenkamp—looking very much the part of a young founder, with tousled brown hair and a gray sweatshirt from his alma mater—doesn’t have an office, just a standing desk with three separate monitors.

Despite his professional success, he doesn’t possess the one thing that so often signifies it in This Town: “DC is all about clout and power,” Hogenkamp says. “And there’s this one metric easily available on the internet of how important you are, which is your number of followers—and I’m at zero. So for a lot of people, it’s just like, ‘Oh, you’re not on social media? You must have zero power and influence.’ ”

Nearly a century after Berliner’s death, the District is a particularly online city. It’s all about who can respond to an email the fastest and who can send the breaking-news tweet to the group chat first. It’s how many followers you have—and who’s following you. It’s memes and influencers. It’s a place where culture and politics are shaped by social media, from Black Lives Matter to Brat. Which begs the question: How do you get attention for a social movement when you’re rejecting the entire attention machine?

“There are all these awesome little bubbles of flip-phone people popping up in cities and towns all across America and worldwide,” Hogenkamp says. “But they don’t know about each other and can’t connect. We’re purposely hard to get in touch with.”

“You Still Have to Make It a Little Palatable”

To help people unplug, Hogenkamp has a million ideas, big and small. He’d like to see tech detox centers—think White Lotus–style phone rehab. He’s tried developing tech that helps people be anti-tech, including an app allowing them to bet with friends on who uses less screen time and to reward kids with allowance for limiting their online usage. He also talks about buying an abandoned property next door to his house to open a sauna and steam room. “Obviously, no phones there,” he says. “It’s just inhospitable to electronics.”

As much as Hogenkamp wants to create offline spaces that are accessible to all, most of those that exist already tend to be luxury experiences, whether super-high-end restaurants or resorts. “A lot of celebrities are increasingly gravitating to the no-phone thing,” he says. “I think it might become kind of a status symbol of the elite.” Just look at what Hogenkamp calls the “flip-phone Mount Rushmore”: actor Michael Cera, director Christopher Nolan, and pop star Rihanna—though she has been spotted recently with an iPhone. (In Washington, Democratic senator Chuck Schumer famously uses a flip phone.) Of course, if you’re rich and famous, you probably have an assistant with a smartphone. Hogenkamp does.

Can the smartphone-free lifestyle work for everyone else? Besner and a couple others recently started piloting what he says is an “experimental incubator for the offline-curious,” called Month Offline. Small cohorts rent flip phones for a month, supporting one another with meetups. “One of the hardest things when you get into this is you feel isolated,” Besner says. There’s an element of reflection—“kind of like an AA group for phone addicts”—but also fun weekly get-togethers and challenges, like taking photos with a disposable film camera to see what people capture when they don’t have unlimited shots. Fittingly, the group doesn’t have a website, just a number: 844-OFFLINE.

Meanwhile, Rock Harper, the DC chef of Hell’s Kitchen fame, recently launched regular phone-free nights at his H Street bar, Hill Prince, where he’ll host DJ sets, comedy shows, book clubs, dining experiences, and other very IRL activities. He’s also toying with other ideas—maybe you get happy-hour deals all night if you agree to go phone-free, or phones are restricted everywhere but the patio, like a smoking section.

“I grew up in the club, where if you wanted a girl’s number, you had to try to find a pen and a piece of paper or memorize a number,” Harper says. “My question right now is: How can I help us remember—or introduce to some of the younger folks who haven’t had it—the power of being present?”

Harper is strongly considering creating a fully present, fully offline bar at Hill Prince or elsewhere, but he’s not sure everyone else is there yet. “It’s just like with cuisine, right?” he says. “As a chef, when you introduce something new or kind of innovative or novel, you can’t just do it. Even the best chefs that have the most captive audiences, you still have to make it a little palatable. If I just say, ‘No phones this week,’ you’re going to piss a lot of people off.”

“People Have Started to Understand”

In February, the New York Times published a follow-up article about the Luddite Club. The response was overwhelming. “We got, like, 50 emails every single day,” says Lane, the club’s founder. “A lot of people wanted to start Luddite Clubs for, like, weeks and weeks and weeks. We raised $10,000 doing nothing.” DC’s very informal adult chapter received about a dozen inquiries.

Policy changes are also brewing. Last summer, then–surgeon general Vivek Murthy called for social-media platforms to come with warning labels, like packs of cigarettes. He noted that young people who spend more than three hours a day on social media double their risk of anxiety and depression. A bipartisan group of senators has proposed legislation that would ban those under 13 from social media. Similar efforts to prohibit phones in schools—a goal supported by current Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.—have been gaining traction nationwide, including in Virginia, which began making the move for K–12 students this year.

Lane believes a broader cultural shift is underway and that hundreds of thousands—if not millions—of people in America don’t like the state of their tech use and want to make a change. “Four years ago, I got rid of my smartphone and literally everyone in my life was like, ‘What are you doing? That’s so weird,’ ” Lane says. “The past couple of years, people have started to understand. It does feel like things are really coming to a head.”

Recently, I started noting the way people in my life talked about their phone use. Nobody seemed happy—including me. I thought about the conflicting relief and shame I feel as a mom bribing my kids with their screens so I can look at mine. Or the way I beat myself up for wasting so much time on Instagram while simultaneously feeling I should be on Instagram more to build my following and “brand.” Yes, social media is important to my work—but if I’m being honest, not to the extent that I use it.

So one weekend, I deleted all the social-media apps from my phone: X, Instagram, Threads, Bluesky, Facebook, TikTok. (Hogenkamp is right: Journalists are the worst addicts.) There was something liberating about it, like setting an away message for vacation and knowing nobody will bother you. I felt a slight air of superiority, too—I’d broken free! But in quiet moments throughout the day—sitting on the Metro, waiting for dinner in the oven—the panic and discomfort of boredom bubbled up. I resorted to other distractions, like reading the news or a book

Then it was Monday. I re-downloaded most of my apps and returned to my mindless scrolling. Still, there have been a few small victories. I haven’t gone back to TikTok, which for me was the most time-sucking platform, and I try to be more mindful of how much I need to be plugged in for work—and the lies I tell myself to the contrary. It feels like I have something by the tail. Wombat or elephant? Like Hogenkamp, I’m not sure yet.

This article appears in the June 2025 issue of Washingtonian.