In 2018, the National Air and Space Museum began renovating its facade and all 20 of its galleries—and on Monday, July 28, visitors will be able to head through the museum’s reopened National Mall entrance and explore five new and revamped halls, as well as enjoy an updated IMAX theater with 375 new seats.

Washingtonian recently attended a museum preview event. Here’s what to see in each of the halls.

Boeing Milestones of Flight Hall

Planes hanging from the ceiling, wind tunnel fans sticking out of the wall, rockets reaching up from the floor—it’s no wonder this cavernous room is one of the museum’s most popular areas.

Wandering the renovated exhibit, I gravitated toward the shiny, spider-legged Lunar Module LM-2, which has returned from storage. I found it fascinating that a spacecraft meant to help astronauts land and take off from the moon was wrapped in orange and yellow foil—what appeared to be the same material I use to package birthday gifts. Jeremy Kinney, one of the museum’s curators, told me the foil is lightweight, and that aerodynamics don’t matter in a vacuum.

This gallery is also bringing back one of the few items you’re allowed to touch: a moon rock. It’s part of the 840 pounds of rocks and soil that astronauts brought back to Earth in 1972 to help geologists study the history and composition of the lunar surface.

“Aerospace and Our Changing Environment” in the Allan and Shelley Holt Innovations Gallery

Highlighting how aerospace technology shapes our lives, this new room will rotate its themes and exhibits every 18 to 24 months. It currently explores how aviation technology helps us understand and mitigate climate change.

The most eye-catching element was a replica of the Soviet Vega balloon, suspended and glowing orange, with a diameter of 11 feet. In 1985, the USSR released the probe to Venus’s atmosphere to record data including temperature and wind speed. The room also showcases flying technology that measures Earth’s climate. On display were satellites that photograph land, water, ice, and plants to assess how they have changed, and low-flying drones that spray crops with pesticides.

On an interactive screen, a sliding tool compares photos of a glacier from 1910 and 2016 to reveal how its ice has melted. The room also demonstrates how astronauts can teach us about living with minimal resources. Space crews grow crops on stacked shelves, and astronauts only need one gallon of water a day.

World War I: The Birth of Military Aviation

Kinney, the curator, says that while this reimagined WWI exhibit is about conflict, it’s “also about the people. Why are they fighting? What do they hope to achieve?”

The human aspect of the war is apparent when you enter the room: you’re greeted by an old aviator outfit that resembles a hazmat suit. Its dark beige billowing body has a cinched waist and fur-lined hood. Accessories include alien-esque black goggles with silver rims and thick buckled boots—these protected aviators from freezing temperatures, wind, rain, and hot engine oil.

WWI led to the widespread use of aircraft for military purposes, so the gallery features several warplanes, including the SPAD XIII “Smith IV” high-speed diving plane and the Fokker D. VII from Germany. In front of the Sopwith F.1 Camel is plaque explaining how the fighter became well-known in popular media—most notably, it was the plane Snoopy imagined his doghouse becoming during his fantasy dogfights with the Red Baron.

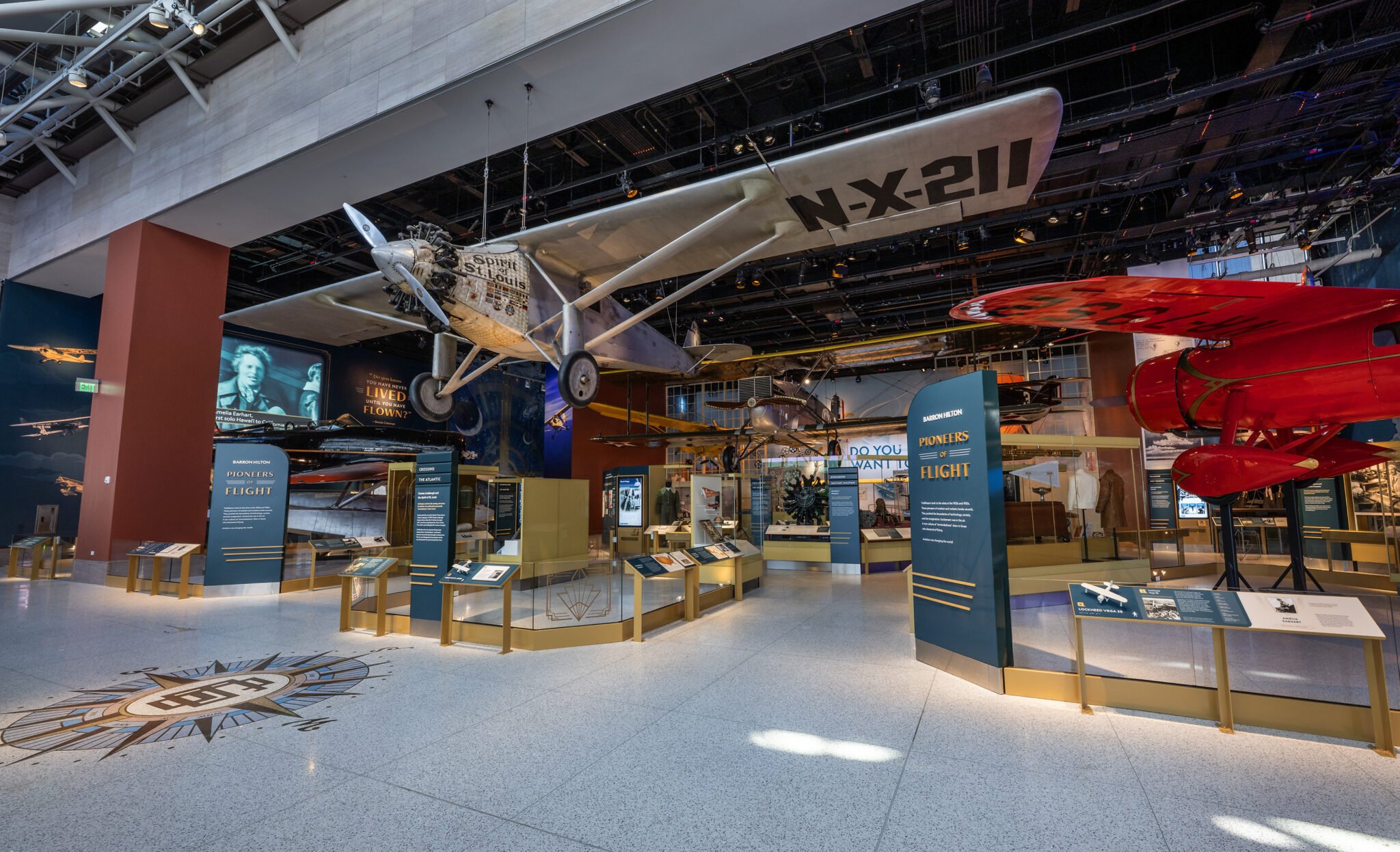

Barron Hilton Pioneers of Flight

Celebrating “the golden age of aviation,” this is one of the museum’s original galleries. Its makeover showcases aviation developments in the 1920s and 1930s, when Robert H. Goddard (“the father of modern rocket propulsion”) launched the first liquid-fuel rockets and Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart flew across the Atlantic Ocean. A model of Goddard’s rocket blasts up in a clear tube at the touch of a button—and if you venture beyond Lindbergh’s Spirit of St Louis plane and Earhart’s Little Red Bus, you can find a big toy model with fake screws for imaginary repairs. “If I was at an event and had a couple of drinks, I’m definitely playing with these things,” a woman said while she twisted a bolt mounted to the plane.

Futures in Space

If you lived for more than a year in a 3D-printed Mars simulation, what would you miss most? The answer for Anca Selariu, a microbiologist who spent 378 days in a 1,700-square-foot building designed to replicate life on Mars: the feeling of wind on your face.

From a dim room in this brand new gallery, you can listen to Selariu and other scientists describe how cooking helped them feel less lonely during the simulation, where messages to and from the outside world took up to 44 minutes to send and receive. She says she is hopeful that humans will get to the real Mars, a cold, inhospitable planet that takes seven to ten months to reach.

This exhibit also asks questions like, “Should robots have genders?” and “Why go to space?” A touchscreen offers answers to the latter, including finding new places to live and answering scientific questions. Another reason is to communicate with nonhuman life—to that end, NASA included “Sounds of Earth,” a golden record containing various music and recordings, with the Voyager space probes that were launched in 1977 and have now reached interstellar space. (You can read more here.)