If you expect nothing but highfalutin political analysis or inside-baseball yakety-yak from Washington’s memoirists, then you’ve never read Rax King. Though she lives in Brooklyn now, King was born and raised in the DC area. Her new essay collection, Sloppy: Or, Doing It All Wrong, is an unblushing inquiry into bad habits—which she has been thinking a lot about in the years since she got sober. Along the way, readers will encounter various nuggets of local interest, including the District’s arcane laws for strip clubs (King worked at a few around the city) and her childhood classmate who ran a sophisticated organized retail theft operation out of a tent in Rock Creek Park.

Sloppy’s spiritual reverence for the ugly parts of life makes it a fitting accompaniment to King’s 2021 essay collection Tacky: Love Letters to the Worst Culture We Have to Offer and her podcast Low Culture Boil, which she and her co-host Amber Rollo dedicate to those among us who have ever asked ourselves: “Would Susan Sontag have enjoyed Jersey Shore?” Sloppy hits shelves today, and King will visit Politics and Prose in Union Market on Thursday. In the meantime, we chatted with her about the new book, her favorite DC haunts, and why the hell she left her beloved hometown for New York. Read our interview below.

You’ve said that you initially wanted Sloppy to be a memoir about addiction, but that it kind of evolved to reflect broader themes about “the life of a quiet fuck-up.” One writer to another, how do you balance writing about painful things with humor and conviction?

I just don’t feel embarrassed by most of the horrible things I’ve done. Things that other authors might feel ashamed of or want to couch in fiction, I just don’t have that specific shame. And the things that I do feel embarrassed or ashamed about—I just don’t write about them. So what reads as very vulnerable to a lot of people doesn’t feel that vulnerable to me. This is stuff that I’m excited to talk about because I think it’s funny or I think that it’ll be relatable to somebody, and the embarrassment factor doesn’t typically come up so much. But once in a while—like when I was reading the audiobook for Sloppy—there were definitely a couple moments when, reading something out loud, I thought, “Dang, this is some rough stuff, actually.” And that, to me, is a signal that something really belongs in a memoir—if, when you encounter it, it feels really scary and fucked up to say out loud. That’s the stuff that’s most worth writing for me.

I would love to hear about how you decided to expand from the idea of addiction to the other parts of your life that it touched.

The essays in there that are most straightforwardly about addiction–those got written first, and most of them got written within the first year that I got sober. I was just going out of my head, felt awful all the time, like a pubescent teenager. I [was] having so many feelings, and I [had] no sense of how to manage them. So I wrote about them. The essay “Proud Alcohol Stock” was the first in the bunch. As I was trucking along and trying to pitch this book to my editor, Vanessa Haughton at Knopf, what she ended up saying was: “This doesn’t seem as much like a book just about addiction. It seems like it’s about bad habits and your relationship to your own bad habits.” And I had kind of boxed myself into a corner by that point with the addiction angle. That opened the door for me to cover all kinds of stuff, including addiction in this more holistic way, where it’s no longer just about, “I was really into this drug for a while.” It becomes more about, “What does that say about my person? What does that say about my character and the changes I’ve undergone? And how can I relate that to what it’s like to be any human being?”

Does writing about yourself so introspectively ever feel crazy? Do you ever feel kind of like you’re doing therapy on yourself?

Sometimes. The part of this whole process that is most explicitly therapeutic happens very early on in the drafting process, when I just need to get the stuff out of my brain and onto the page in what shape it feels like showing up. And that stuff is close to unreadable. If I cross-check it against my diary from 11th grade, the tone is basically the same. It’s just like, “Poor me. Everyone’s wronging me all the time. Everything sucks.” And it takes a good amount of sitting with my own thoughts, which comes in the form of revision and getting extensive feedback from other people. And then at that stage, it’s a little less explicitly introspective and a lot more outward-reaching, connecting all my “poor me” stuff to reality and realizing, “Poor me, but also, poor everybody.” Everyone’s kind of fucked in roughly the same ways. And so I could just pity myself about it, or I could try and write my way through it and hopefully get to the other side of it.

There are a lot of nods in the book to your upbringing in DC. Where in the city did you grow up?

All up and down the Red Line. I lived for a time in Chevy Chase, and I lived for a time in Rockville with my dad. And probably the bulk of my adolescent/early-adult development in DC was around Mount Pleasant and Woodley Park. Those are the two apartments that I associate most closely with my DC adolescence.

Do you ever visit now?

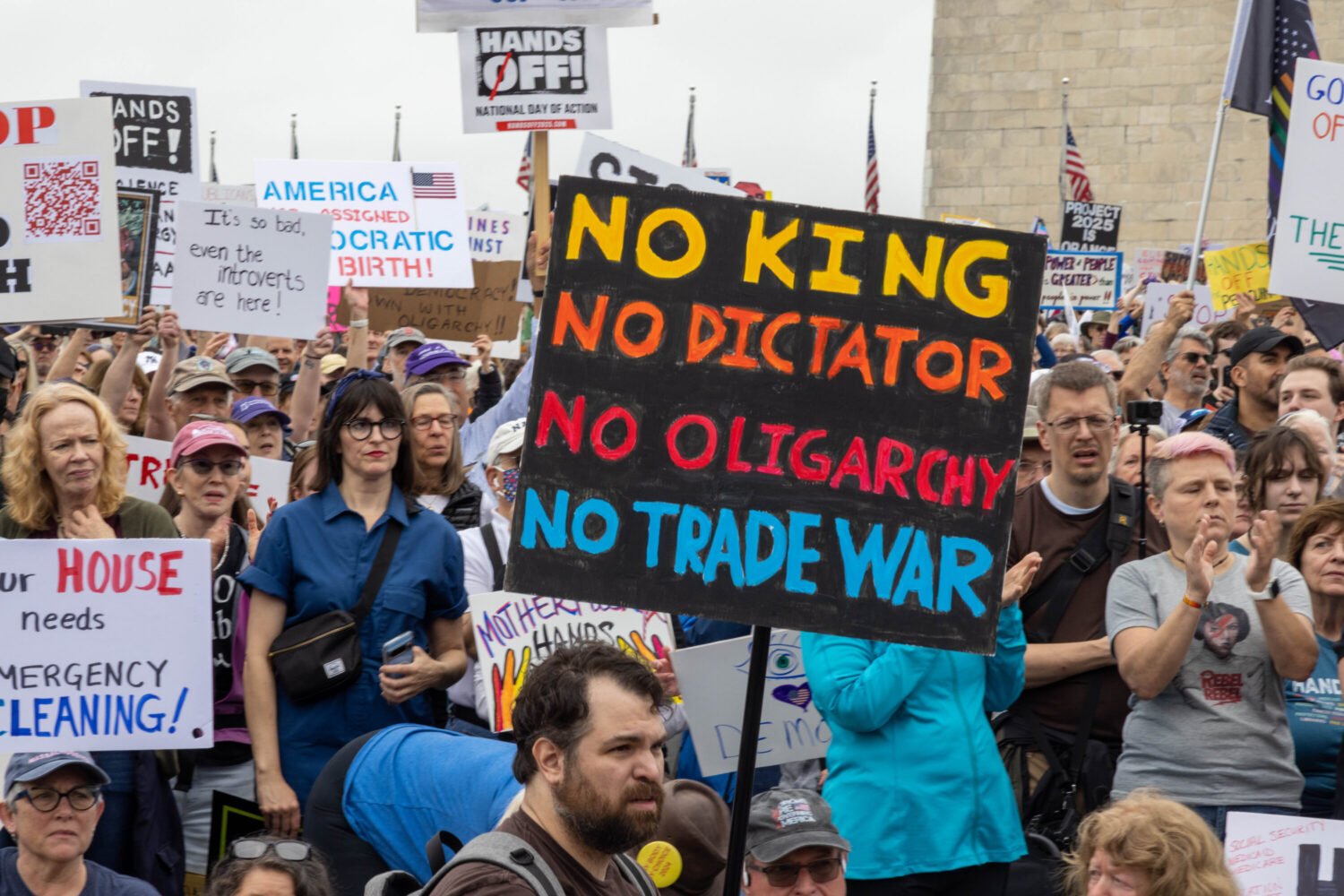

All the time. … On the cutting room floor for Sloppy, there is an essay about just how much I love DC. It just didn’t quite fit with the rest of the theme, so it’s gonna end up being published someplace else. A big part of why I wrote that essay—and also why I wrote the book, and why I write about myself—is I really want to give an angle on DC that isn’t just politics and media and various industries that constitute the city’s administrative and professional center. I grew up there, and I was just some guy living there, and that was who my friends were—just people minding their own business under this canopy of the federal government, as Ian MacKaye calls it. And so, places that I hung out were not the same as places where aides and contractor types hung out. When they complain about DC and how buttoned-up and boring it is, it’s always felt like we were living in two different cities.

What are some of your go-to spots around the city?

Obviously, the Black Cat. Other music venues also played a really important role for me. Fort Reno, those free outdoor summer concerts—that was where I was from June through August most years. And a couple places that have shut down: The Rock & Roll Hotel was a huge part of my early adolescence. And Fight Club, too—this really gnarly bar where they had illegal shows sometimes. DC has always had such a robust culture of all-ages shows, and I feel a huge amount of gratitude for growing up in a place that had that kind of culture to offer me when I was young and impressionable.

Sloppy also taught me that DC used to have some really stringent rules about stripping.

I had a hard time confirming that for sure. I was digging into old [DC Council] meeting records and stuff like that, trying to identify the precise zoning law. So if any Washingtonian readers can help me out by finding the zoning law that dictates that strippers in DC have to stay a certain distance away from their customers, I would be much obliged. But the way it was explained to me when I first started at DC strip clubs was that we can’t offer lap dances—as far as I can tell, that has since changed. So because you can’t sell lap dances and give the club a cut of that money, your job is basically to hustle cocktails as hard as you can and simultaneously shake these men down for tips for yourself. And I will say, I ended up stripping in a number of different locations, and the house fee that I paid in DC strip clubs was always super low for that reason. It was a very weird rule, and it felt like something must be kind of illegal about hustling these drinks so hard.

Your essay on how Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives helped you heal from leaving your abusive husband got you nominated for a James Beard Award—so it’s safe to say you’re a food writer. You also write in Sloppy about your time in the food-service industry. What are some of your favorite DC restaurants, whether they still exist or not?

Since they went up, I’ve always loved Bub and Pop’s. A dope sandwich place. And also just down the street, actually, the Greek Deli. Just some good-ass Greek food. And God, Kostas, the guy who owns it—he’s just really fun and cool. And it’s a really quirky little place. [Since this interview took place, Bub and Pop’s relocated from Dupont Circle to NoMa and Kostas Fostieris has retired from the Greek Deli.]

Clyde’s, definitely. It just always meant so much to my dad and me. It was our place. Great burgers at Clyde’s, too—great burgers at every restaurant that’s owned by the Clyde’s people. And as far as places that have deceased, I gotta give a shout out to Luigi Pizza. They were just delicious. It was one of those real old-school pizza parlors with the red-and-white tablecloths. I have no idea why they went under and I wish they hadn’t.

I gotta shout out a couple great half-smokes, since that’s DC’s contribution to meat culture. DCity Smokehouse, great barbecue place. I love it there. And Meats and Foods, which is more like you buy some sausage and you take them home, but I believe you can get sandwiches there as well. I have, like, three Meats and Foods T-shirts for some reason, and so I’m always promoting them at yoga classes.

All this love for DC, and now you live in New York. What happened?

Honestly, I’m still kind of mad at myself. I think all the time about moving back, because I love DC in a way that I don’t quite love New York after ten years of living here. But it’s a lot of reasons. I think living in DC and not working in those professions that weigh so heavily on the city, you start to feel kind of like a failure. And I just didn’t think I could have the writing career that I hoped to have if I stayed. And then I also had this moment back in 2015 when I moved [to New York], when I looked up and realized most of my friends had moved. Most of the people I grew up with didn’t live there anymore, and a lot of the people that I hung out with socially, they had gotten priced out to Baltimore. They just weren’t all with me every night of the week, the way I had gotten used to, and I was lonely. And I moved to New York to chase friends, and then finally, also to chase a boy. There was a boy here, and I followed him, and we broke up and I never left.

I miss it, though. At this point, I’m remarried. I’m married to a good husband this time, and he’s in a labor union, and they’re local to New York. He has to stay here for work. So all my little hinting about how beautiful DC is, and all the great architecture and fun stuff to do, and how much I’ve always wanted to raise a kid in DC—all that stuff is going to be falling on deaf ears for a little while, but I do miss it all the time. And to the people who are here and feel like they want to leave because the vibes are so fucked right now: Maybe don’t. Maybe stay and enter the cool zone with your neighbor.

Rax King will appear at Politics and Prose at Union Market on Thursday, July 31, at 7 PM. The event is free and seating is first-come, first-served.