Federal employees have been living in a constant state of uncertainty since late January, dealing with mass firings, court decisions that swing back and forth, and an administration that employment lawyers say is systematically dismantling longtime protections. In DC, where federal workers make up 43 percent of the workforce, thousands are scrambling to understand what comes next and turning to labor lawyers for guidance.

It’s not just that jobs are disappearing—it’s how they’re disappearing that’s left federal workers reeling. “Reductions in force (RIFs) have never been done this way before,” says DC attorney Debra D’Agostino. Traditionally, Congress passes a budget that cuts funding for an agency or program, and then jobs are adjusted accordingly. Workers are transferred, retrained, or provided with proper notice and severance based on seniority and performance. “It was all done in a way that people knew what was happening, why it was happening, and could make informed decisions about their own situation,” she says.

It’s not just that jobs are disappearing–it’s how they’re disappearing.

Instead, we’re now seeing what D’Agostino calls “RIFs by executive order.” The administration is bypassing careful documentation and procedural safeguards, resulting in employees getting fired without proper justification or having disability accommodations rescinded without review. “There were systems in place that everyone previously more or less respected, that were designed to prevent things like this from happening,” says DC attorney Sarah Nason. “Now all of that is being ignored.”

It’s easy to understand why those affected may choose to accept their fate, but federal employees aren’t powerless. Their employment rights remain largely intact, leaving many avenues to fight back—and lawyers are encouraging aggressive use of these options. For instance, the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB) continues to process cases despite Trump’s firing of the Biden-appointed chair, Cathy Harris. “[Administrative judges] are hearing appeals on both probationary terminations and RIF cases,” D’Agostino notes. However, the MSPB doesn’t have a quorum of members, meaning cases won’t reach final decisions for several months. But even if the MSPB becomes completely dysfunctional, DC attorney David Wachtel points out a recent Fourth Circuit decision in National Association of Immigration Judges v. Owen suggesting that federal employees may be able to bypass it entirely and go straight to federal court.

The Office of Special Counsel and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) also offer paths for resolution, particularly for whistleblower or discrimination cases. Both D’Agostino and Wachtel admit that attorneys have limited faith in these forums, though, as they’ve become slower and less effective. Still, they advise people to file complaints.

For federal employees who haven’t been laid off, Wachtel recommends starting documentation now. They should keep a detailed log of dates, events, and conversations but be strategic about what they record. “You can write outlines of the conversation, like ‘On this date, I met this person and we talked about this subject,’ ” Wachtel says. He advises people to avoid including classified or sensitive information that could create additional problems. If you’re in a union, it’s also important to have a copy of your collective-bargaining agreement. Regularly check your electronic personnel records. Wachtel and Nason have seen RIF notices with incorrect employment dates that make workers appear to have less tenure than they actually do.

Most important, know your deadlines. Federal employees typically have 45 days after a discriminatory act to file an EEOC complaint. Don’t wait for the perfect case, Wachtel says. Submit by the deadline and refine the complaint later. Once you’ve filed, be prepared to wait. Cases related to federal employment typically take several months to resolve. (Decisions are still being made on cases filed during Biden’s presidency.) D’Agostino predicts it could be another year before the Supreme Court decides on the legality of Trump’s actions.

Though it may feel futile amid all the uncertainty, D’Agostino emphasizes that legal action serves a purpose beyond individual justice. Success may look like back pay or reinstatement for some, but for others it’s about ensuring that the Trump administration follow the rules. For those who stay and fight, the message is clear: The systems designed to protect federal workers may be strained, but they’re not broken.

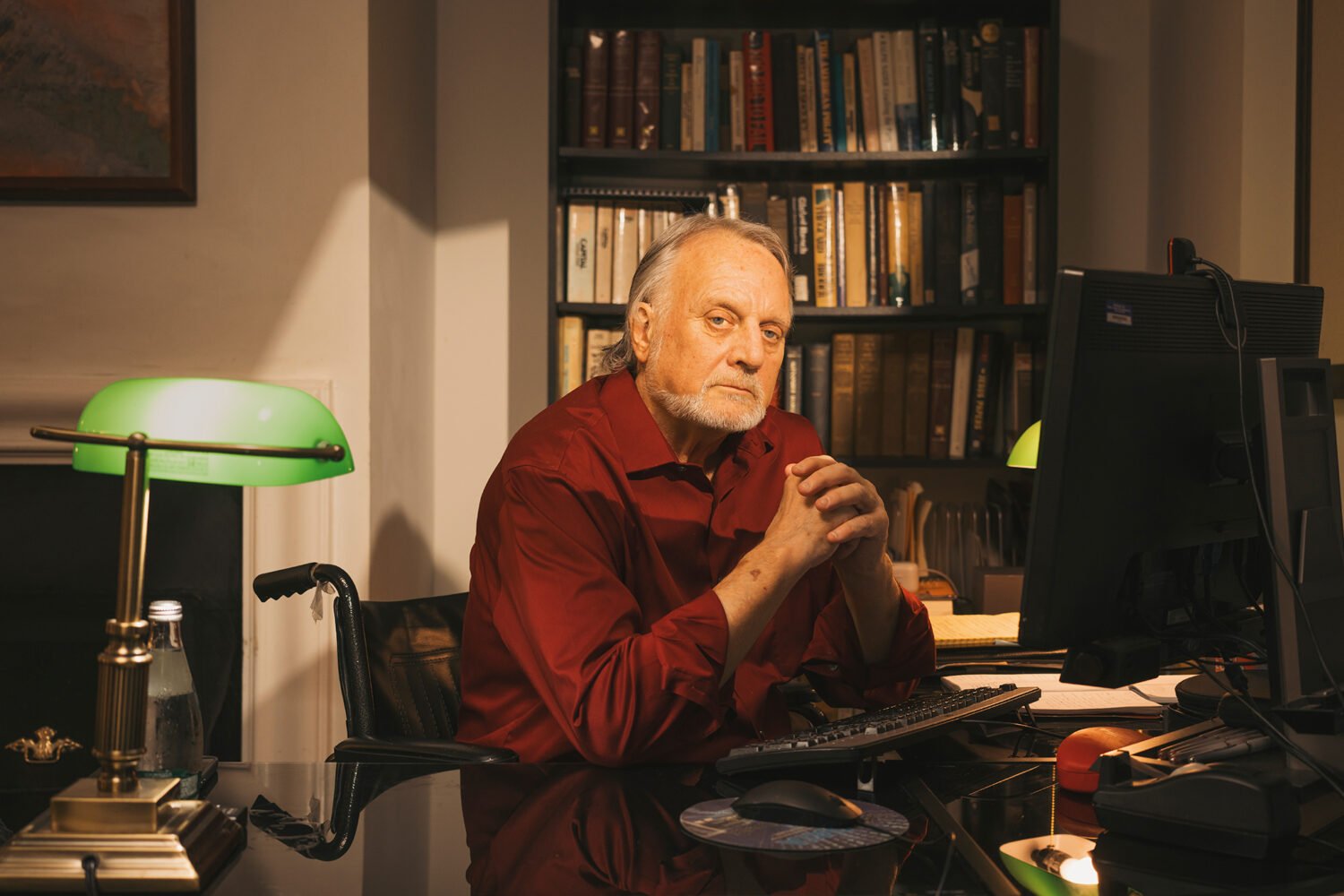

Top Employment Lawyers

Federal workers are dealing with a lot of challenges under the Trump administration, including mass terminations and threats to civil-service protections. Although recent court rulings have blocked some workforce cuts, the legal landscape remains uncertain, making it more important than ever to consult attorneys who are experienced in employment law. While many of the following attorneys—who were selected through a peer survey as well as our own research—handle any type of work-related law, they have particular expertise in federal employment issues, from wrongful termination and discrimination to whistleblower protection and security-clearance disputes.

Kristen Alden

Alden Law Group

Katherine Atkinson

Atkinson Law Group

Andrew Bakaj

Compass Rose Legal Group

Michelle Bercovici

Alden Law Group

John V. Berry

Berry & Berry

Subhashini Bollini

Correia & Puth

Linda Correia

Correia & Puth

Debra D’Agostino

Federal Practice Group

Rosemary Dettling

Federal Employee Legal Services Center

James Eisenmann

Alden Law Group

Joshua Erlich

Erlich Law

Elaine Fitch

Kalijarvi Chuzi Newman & Fitch

Gary Gilbert

Gilbert Employment Law

Mary Kuntz

Kalijarvi Chuzi Newman & Fitch

Alan Lescht

Alan Lescht & Associates

Kel McClanahan

National Security Counselors

R. Scott Oswald

Employment Law Group

Jonathan Puth

Correia & Puth

Debra Roth

Shaw Bransford & Roth

Diane Seltzer

Seltzer Law Firm

Michael Vogelsang

Employment Law Group

David Wachtel

Trister Ross Schadler & Gold

Mark Zaid

Mark S. Zaid, PC

This article appears in the August 2025 issue of Washingtonian.