I never met the previous owner of my apartment in Cleveland Park, but she left two plastic planters of crusty dirt and dead marigolds on the windowsills and taped a note to the kitchen counter. “The windows get a lot of sun in the morning,” she wrote. “Marigolds do well.”

It was May 2005, and I had just moved to DC from Boston. Marigolds are summer annuals—the ones in the planters must have been dead for six months at least. They had turned to straw. I threw them into a dumpster in the driveway, washed out the planters, and drove to the nearest nursery.

I hadn’t visited a nursery since the early 1990s, when I was married and lived in a house with a yard in Green Bay, Wisconsin. But like churches and football stadiums, nurseries are universal and unchanging. The smell of plants and wet soil, filtered light through the domed roof, shelves of flowering plants in plastic containers—all brought back memories of the flowers, vegetables, and herbs I’d grown in our yard.

There was an entire shelf of marigolds, but their prim yellow bonnets had always struck me as precious. I bought petunias instead—one bright-pink six-pack and another much paler, almost salmon.

Leaving the parking lot with the flowers and potting soil in my car, I almost expected to be on Webster Avenue in Green Bay, where the nursery and the grocery store used to be side by side around the corner from my house. In Wisconsin, though, my trunk would have been packed with plants and I wouldn’t have bought soil in an eight-quart bag.

I had started my garden in Green Bay by hiring a guy with a rototiller to dig up the back yard. I ordered a truckload of topsoil from a landscaping company, had it dumped in the driveway, and moved it one wheelbarrow load at a time to the vegetable plot, the flower garden, and the herb patch. The substance I moved so laboriously was called ground, as in “I’m calling to order some ground.”

The window boxes represented a totally different kind of gardening, and the bag of potting soil made me nervous. I was abysmal with houseplants. I had drowned and parched them in turn, placed them too close to the window or too far away. Not one had lasted a year. But petunias in window boxes turned out to be as hardy as the zucchini I used to grow. They loved the bright light in the east-facing windows of my third-floor apartment, and my old strategy for the garden—when in doubt, water—worked for them even though it had caused the demise of many a houseplant.

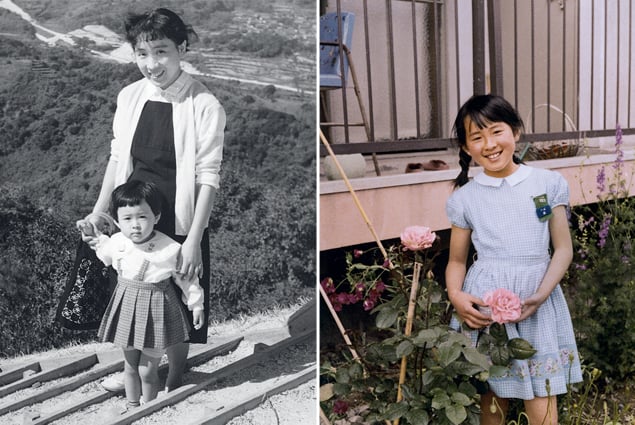

All over my new neighborhood, I saw huge, colorful clusters of petunias, annuals I associated with the garden my mother tended during my childhood in Japan. Every morning, I ran to National Cathedral, circled its terraced gardens, jogged down the hill into the hazy green canopy of Rock Creek Park, and followed one of the winding paths through the National Zoo to the row of cherry trees across the street from its gate. Along the way, I recognized other trees and flowers from Japan: the blue hydrangeas my mother had loved, the small maples whose leaves turned red in early summer, the Japanese laurel with leaves spotted yellow.

After 22 years in the Midwest and six in the Northeast, I realized I was living once again in the climate zone of my childhood.

• • •

My mother planted a flower garden every spring in front of our apartment in Ashiya, a suburb of Kobe where our family lived in the 1960s. Her sweet peas climbed a lattice of bamboo sticks and cotton twine to the bottom of our balcony and wound their way up the railing. By June, they were so thick that we could hardly see through the brass bars of the railing. When the vines reached the handrail, they doubled back down and began to produce seed pods that resembled miniature snow peas.

In the fall, my mother collected the seeds in small white envelopes she kept inside a tin canister for the next year. She let the other annuals die out and replaced them every spring. I think she was partial to the sweet peas because they climbed the lattice she’d made for them and bloomed on the balcony where we sat on breezy afternoons. Like the sparrows who ate the bread crumbs we scattered under the balcony chairs, they were unafraid and gregarious—eager, even, to be near us.

My mother planted only annuals because the apartment was meant to be a temporary home. Our building had 32 rental units occupied by young families like ours who were saving to buy a house. My mother had some of the women over to tea every week, and in late summer she would send them home with zinnias, snapdragons, and sunflowers from her garden. Everyone marveled at the flowers she got out of a patch no larger than eight by ten yards.

When we moved into a house of our own in 1967, my mother had ten times as much space for gardening. She could finally cultivate perennials and bulbs that would come back every spring with more flowers. All around the house she planted roses, hydrangeas, forsythias, daffodils, hyacinths, tulips. My grandmother, who lived in the country, divided the peonies and irises from her garden and brought them on the train in plastic bags of black dirt and wet roots tucked into her suitcase.

I was ten years old, too young to know that 100 acres of perennials couldn’t have saved my mother from her unhappiness. She must have hoped that the new house would entice my father to spend more time at home. Instead we seldom saw him, and his numerous girlfriends started calling every night.

• • •

In 1969, the spring after my mother’s suicide, the yellow roses she had coaxed to twine around the garden gate began to bloom. My grandmother’s peonies raised their blurry pink fists under our living-room windows.

The woman who moved into our house—she and my father would be married within a year—hated being surrounded by my mother’s things. She threw out the tapestries my mother had embroidered, but she couldn’t rip every plant out of the garden, so we had to move. The house my stepmother chose had a patch of grass and a few shrubs pruned by a professional gardener.

My stepmother told me that my mother had been a failure as a wife and mother. Maybe she believed she was smarter than my mother had been. When my father started seeing his other girlfriends again, my stepmother threatened to leave him and blamed me. I made her miserable, she claimed, by talking back to her. She sat clutching the handle of the suitcase she’d packed, while my father begged her to stay and slapped my face to demonstrate his love to her.

I wanted to show everyone I was far from all right, but aside from neglecting my homework or talking back to teachers, I couldn’t imagine what I would do to get into trouble. I attended a private girls’ school where wearing jeans to class or buying food from a street vendor—instead of at a proper cafe or bakery—was everyone’s idea of rebellion. Not counting my mother, I didn’t know anyone who had done serious harm to herself or her family. Besides, it was pointless to ruin my own life to spite my mother when she was already dead.

Being raised with all those flowers must have diminished my capacity for rage and self-destruction. No matter how angry I felt on the surface, there was always a core of cool logic underneath, as though my heart were made from those wet black roots my grandmother had dug up from her garden—a homely thing cultivated to survive.

In 1977, I left to study writing at a small college in Illinois, knowing I’d never move back to Japan.

• • •

In July 2005, the petunias I’d planted in Cleveland Park were spilling out of the window boxes, trailing their pink flowers down the brick wall of my building. One morning, I heard a loud buzz—the sound a minibike might make starting up—while I was clipping the blossoms that had faded. A tiny stream of air, a micro-breeze, blew across the back of my hand. The next moment, a hummingbird and I were face to face, with only a few inches between us. His ruby throat at eye level, he hovered upright with his wings beating, like a swimmer treading water. After five, six seconds, he flew backward, plunged down to the driveway, and disappeared. For the rest of the summer, I noticed hummingbirds—male and female, though never together—sipping nectar from the petunias in the early morning and at dusk.

Hummingbirds don’t build their nests, raise their young, or migrate as pairs. The male establishes his feeding territory, mates with several females, and takes off for the birds’ wintering grounds in Mexico or Central America. The first male I saw in July most likely left the area in early August and was replaced by others who were flying through. Not a single male hummingbird came to my window after early September, but a female lingered into October. With her white breast and slim body, she reminded me of a fish. In the last few weeks, she was at the flowers several times a day, gaining weight for the long migration and looking, finally, more like a bird. The last day I saw her was October 4.

Soon after, the petunias grew brittle and their leaves turned brown. The dried-up stems could hardly support the few buds that were still opening. When the wind picked up, I understood why the former owner had left those marigolds to wither. Empty planters would have blown away. Still, it was depressing to keep dead flowers for ballast.

I returned to the nursery a few days before Halloween and found almost all the shelves covered with pansies. Unlike the fall mums corralled onto side tables, the pansies weren’t discounted—they were expected to bloom for quite a while. I recalled the fountain-size “flower clock” planted with changing displays of annuals in downtown Kobe. Because it was in a public square in front of the train station, I saw it every month throughout my childhood and adolescence: first with my mother on our shopping trips downtown, then with my school friends on our way to the movies. I could picture the long, red second hand moving over a sea of blue pansies, with people in winter coats standing around. That must have been in January or February. Since leaving Japan, I’d never lived in a city where you could have flowers in winter.

The dozen pansies I planted in the window boxes didn’t stop flowering even when it snowed. On a few cold nights in February, they shriveled up and stuck to the frozen soil, but they sprang back when the sun came out. They were happier in cool weather, blooming through March, April, and the first week of May until the heat withered them. In Wisconsin, pansies had been summer flowers. In DC, they held my window boxes in place until it was time for petunias and hummingbirds again.

• • •

In Green Bay, the neighborhood where my husband, Chuck, and I lived had been developed during the Depression, with each lot intended to accommodate a vegetable garden. Our back yard was half the size of a football field.

The first occupants may have been survival gardeners, but by the time we bought the house in 1986, the yard was an expanse of manicured lawn. In a few small clusters around the house, the former owners had planted bushes and covered their roots with mounds of tree bark processed to look like charcoal briquettes. The arrangement reminded Chuck of suburban gas stations. To me, our back yard was an American version of my stepmother’s cropped grass and trimmed shrubbery.

The summer we bought the house, I was 29 and Chuck was 32. We had been living together four years, married two. He was an elementary-school teacher, and I taught creative writing at a college. The former owners, a couple our age, were high-school teachers. I couldn’t fathom why able-bodied people who had their summers off would need a yard so sterile and easy to care for. I decided to turn the gas-station-style landscaping into flower beds while Chuck did other outdoor chores, cutting the grass or raking leaves.

Getting rid of the bark took two summers because the ground underneath was covered with black plastic to prevent anything from taking root. I had to rip it out by the handful before I could plant perennials and biennials that would bloom the whole summer. I didn’t have my mother’s patience for roses, and the only hydrangeas that grew in Wisconsin were the plain “snowball” variety whose dried flower heads rattled around the autumn garden prophesying the destruction of all living things.

Peonies and irises, however, could tolerate the harsh winters. Under our living-room windows every May, the peonies dropped their feathered petals one by one as though they longed to give back every bit of their beauty to the ground that had nourished it. The irises, meanwhile, perfected their elegant origami and quietly folded back into themselves, keeping their own counsel the entire time.

• • •

Gardening gave my summers a structure. I’d go for a run in the morning and work in the garden until noon before sitting down at my desk to write. In the ten years I lived in that house, I worked hard to make the yard look nothing like the one Chuck and I had inherited. It took me a long time to realize that what I loved about gardening wasn’t so much making a home as working alone.

How could I have missed the parable that unfolded in my own garden spring after spring? I was an iris and not a peony. No marriage could give me the satisfaction I found in solitude: running in the early morning before anyone was up, spending hours alone in the garden and then at my desk. I didn’t ask Chuck to help me plan or plant the garden. I didn’t talk to him about the books I was writing until they were published and he could read them along with everyone else. Like an iris, I created in isolation and folded back into myself.

If I had wanted to go on living with another person, I would have chosen Chuck. He was funny, honest, and smart. My need for solitude, though, was growing. When we were first married, I had been content to have a few quiet hours for my writing. Now I needed the morning in the garden, the afternoon at the desk, the weekend riding my bicycle through the countryside, wandering in the woods with my binoculars and bird-watching guide, or driving four hours to Chicago to see museum exhibits, always alone so I could listen to the conversation inside my head.

I moved out, to an apartment across town and then to the East Coast. Chuck, who has remarried, hasn’t lived in that house for several years. The last time I saw our old home, from the window of a rental car, the garage had been painted two colors, like a jester’s costume, and there was a for-sale sign out front. I didn’t have the heart to get out to see the yard.

• • •

I’ve thrown out the plastic window boxes the previous owner of my DC apartment left behind, and I’ve put terra-cotta planters in each of my six east-facing windows. They now comprise an aerial hummingbird garden of petunias and salvias, with two bird feeders hanging from brass planter hooks. The feeders are shaped like miniature flying saucers, each with a pencil-thin rim around the red cover. Hummingbirds have weak feet and legs (they belong to the order Apodiformes, which means “without feet”). They don’t walk or hop on the ground as robins and sparrows do, but they can perch on the specially designed rim as they drink the sugar water inside the reservoir. The perch gives me a better look at the birds than when they flit around the flowers, eating on the wing—which they still do.

My building was built in the 1920s. After 60 years as a rental, it became a co-op in the 1980s, around the time Chuck and I bought our house in Green Bay. It’s a typical big-city co-op—a predominantly single world—the antithesis of the small-town, two-story house that the Green Bay real-estate agent said was “a nice place to start a family,” though Chuck and I never planned to have children. My current building and my old house are parallel universes, and I’ve moved from the universe I didn’t belong in to one where I’m at home.

When I left my marriage, I wasn’t trying to be a hermit. Living with the one person I’d chosen—which meant having to keep choosing him day after day for decades as the two of us changed—was as exhausting as keeping a garden in the wilderness. By the end, partnership seemed impossible, even unnatural, to me. But community is a different proposition. Living among people I didn’t choose, working to establish peace or friendship in spite of occasional disagreements, makes sense to me.

The first hummingbird feeder is in the window next to my desk, so I can look up from my work to see the sudden movement, a flash of color appearing out of nowhere, which is the reward and inspiration for the hours I spend writing alone. The second feeder is in the window in front of my dining table. In mid-June, when the sky remains light till nearly nine, I like to invite my friends to a late dinner. By then, the salvias in the window boxes are tall enough to block the view of the houses across the street.

Sitting at the table, all we can see above the plants are the tops of the trees in the distance and the sky above, gradually darkening. It’s essentially the same view I once had lying on the ground in my vegetable plot between the rows of zucchini and tomatoes. We’re catching the sky between the green leaves I helped make, and if we’re lucky a hummingbird plummets through the blue depth toward us.

My mother, too, was happier in an apartment complex surrounded by neighbors than in a house of her own. The garden on my windowsill is my American replica of her sweet peas on the balcony where she and I once fed the sparrows. I wait for the hummingbird to return one last time at dusk, to kiss the bell-shaped flowers and the sugar water.

Kyoko Mori (kmori@gmu.edu) is author of three nonfiction books (The Dream of Water, Polite Lies, and Yarn) and three novels (Shizuko’s Daughter, One Bird, and Stone Field True Arrow). She teaches creative writing at George Mason University.

This article appears in the April 2013 issue of The Washingtonian.