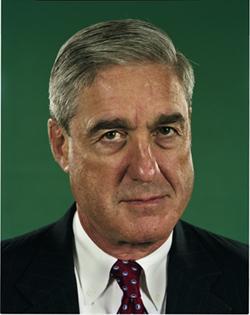

The sun had just come up when Robert Mueller and James Comey walked up to the West Wing of the White House shortly after 7 am on March 12, 2004. Mueller and Comey had been up for much longer. Neither the FBI director nor the deputy attorney general had slept much in the previous week, and that was before al Qaeda terrorists killed 191 people in train bombings around Madrid. It was windy and cool; the thermometer hovered at 40 degrees as the two men prepared to brief the President.

It was, both fully expected, the last time they would enter the White House. In their desks at the FBI and Justice Department were letters of resignation they expected to submit; they would be joined by a dozen other Justice and FBI officials. The only reason the letters hadn’t been submitted already was that the men, at the request of the attorney general’s chief of staff, were waiting until John Ashcroft had recuperated from gallbladder surgery to the point where he could resign as well.

To understand that day, you have to go back to the 73-word oath that kicks off every federal career.

Bob Mueller never got his formal swearing-in as FBI director. The ceremony, one of the government’s nicest traditions, usually comes with the flickering of flashbulbs and applause from the assembled staff followed by brief remarks and a wine-and-cheese reception.

When Mueller was sworn in as US Attorney in San Francisco in 1998, in a sign of the respect he had garnered on both sides of the political aisle, Senator Barbara Boxer attended, the only time she has attended a US Attorney’s swearing-in during her 15 years in the Senate.

Three years later, when Mueller took over the FBI under a Republican administration, he had only a small ceremony attended by his wife, Attorney General Ashcroft, and a few aides. The date was September 4, 2001. The plan was that later in the month the bureau would hold a ceremonial swearing-in.

At the small September 4 ceremony, Mueller raised his right hand and swore: “I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same.”

On that day seven years ago, perhaps a thousand presidential briefings and many thousands of national-security threats ago, he had no idea of the enemies he would face—or that while he was battling terrorists at home and abroad, he would also battle people within the Bush administration who in his view threatened the rule of the Constitution. As the oath says—“all enemies, foreign and domestic.”

Robert Swan Mueller III had sworn the oath seven times. The first time was as a Marine recruit during the height of the Vietnam War. That Mueller would end up in the Marines is surprising. He grew up in a wealthy corner of Philadelphia, a path that led him to St. Paul’s boarding school in New Hampshire.

Even by the standards of elite private schools, Mueller’s class did well for itself: John Kerry was the 2004 Democratic nominee for president, Max King went on to edit the Philadelphia Inquirer, and Will Taft became the top lawyer for the State Department.

For Mueller, it was off to Princeton after St. Paul’s—a path determined, as it was for most of his classmates, by his father’s college choice many years earlier. The key figure at Princeton—whose motto is “Princeton in the nation’s service and in the service of all nations”—was David Hackett, a popular athlete who joined the Marine Corps and died in Vietnam. Hackett’s model of duty and sacrifice inspired Mueller and a handful of his classmates to join as well. “He was always a leader to us,” says Mueller.

In the Marines, Mueller swore allegiance to the Constitution and entered officer training. Two years later, on December 11, 1968—nine days after his prep-school classmate Kerry earned his first Purple Heart in Vietnam—the platoon of Marines led by Second Lieutenant Mueller came under fire in Quang Tri province. The battle earned Mueller a Bronze Star.

“Second Lieutenant Mueller fearlessly moved from one position to another,” the medal citation says. “With complete disregard for his own safety, he then skillfully supervised the evacuation of casualties from the hazardous area and, on one occasion, personally led a fire team across the fire-swept terrain to recover a mortally wounded Marine who had fallen in a position forward of the friendly lines.” The citation praises “Mueller’s courage, aggressive initiative, and unwavering devotion to duty.”

After the war, in which he also received a Purple Heart and the Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry, he returned to the United States and enrolled at the University of Virginia’s law school, where he excelled at law and lacrosse, and applied to be an assistant US attorney after graduation.

Unable to get a federal position, Mueller reluctantly entered private practice before eventually landing as an assistant US attorney in San Francisco, where for the second time he swore allegiance to the Constitution.

“Anyone who takes that oath takes it seriously,” Mueller says. “I would hope they do.”

It was in San Francisco that he first got to stand up in court as the government of the United States incarnate. He took on tough cases and got convictions, rising to become chief of the office’s criminal division until Joseph Russoniello was appointed US Attorney in 1982. Russoniello brought in his own team, and Mueller was demoted.

When Russoniello recently was appointed to a second term as US Attorney for the Northern District of California, Mueller called him and pointed out that he was the only person who had ever demoted him. Mueller joked, “Joe, however many FBI agents you have assigned to your office, it’s now ten fewer.”

Mueller moved east to work for Boston’s US Attorney. Friends say that part of the lure of Boston for Mueller was that he had a daughter with spina bifida and could get her good treatment at Children’s Hospital Boston. He made an instant impression on the office.

Then–US attorney William Weld recalls of Mueller, “You cannot get the words ‘straight arrow’ out of your head. He didn’t try to be elegant or fancy; he just put the cards on the table.”

Massachusetts was where Mueller’s ambition to run the FBI first showed. After William Webster stepped down as FBI director, Weld passed up a chance to be considered. Mueller was incredulous. Weld recalls, “He already wanted to be director of the FBI so bad that he could taste it. He couldn’t understand why I wouldn’t want to do it.”

Mueller eventually succeeded Weld as US Attorney in Boston, appointed by President Reagan, and returned briefly to private practice before getting a call from Dick Thornburgh, George H.W. Bush’s attorney general, who asked him to come down to Justice to help lead the prosecution of Manuel Noriega; Mueller later worked on the Pan Am 103 bombing. The two cases proved to be landmarks: one of the first major international crime prosecutions and the first major terrorist incident involving US citizens. Mueller rose to become head of the Justice Department’s criminal division.

After Bill Clinton took office, Mueller settled into a partnership in the Washington office of the tony Boston law firm Hale and Dorr, now WilmerHale. Mueller never loved private practice. As partner William Lee explains, “It was hard to find as many trials as he would have liked.”

An old Princeton friend, Lee Rawls, says he knew Mueller wouldn’t last in private practice when Rawls referred a corporate-malfeasance case to him. Instead of offering to defend the wrongdoer, Mueller said that the defendant, then in jail, was “right where he belongs.”

Says Rawls: “It’s a transition to go from prosecutor to defendant. It’s a different type of thinking. In his heart of hearts, he’s a prosecutor.”

Mueller’s next step was surprising: He called Washington’s US Attorney, Eric Holder, and asked to be appointed a homicide prosecutor—an entry-level job in the nation’s largest US Attorney’s office. “That really took me aback,” Holder says, “both because of the positions he’d had and that he was at a great firm. The decision on my side was a no-brainer: ‘I’m getting Bob Mueller for that price?’ ”

The move meant giving up more than three-quarters of the $400,000 Mueller had been making each year at the law firm. But he didn’t love the work and didn’t necessarily need all the money. Financial-disclosure forms filed when he was nominated to be FBI director show that Mueller’s wife has several multimillion-dollar trust funds, which provide a modest annual income.

• • •

But Mueller did love homicide. “He was just one of the guys,” Holder says. “He didn’t demand special treatment or receive it. He was doing what he wanted to do.”

In the chaotic US Attorney’s office at 555 Fourth Street, Northwest—the “triple nickel,” as it was known—Mueller was in his element, answering the phone with “Mueller—homicide.” Regimentally organized and brusque, Mueller, who wore a Marine Corps lapel pin, cut a wide swath through the office. “Detectives loved him,” says Daniel Friedman, then homicide-section deputy chief.

Mueller says today, “I’ve always loved investigations.”

Holder recalls that Washington in the mid-1990s was a different city from today: “It was an office that was almost under siege. DC was the homicide capital of the United States. We had a crack problem that had spiraled out of control. Huge numbers of homicides that were mostly in one way or another drug-related, huge numbers of violent crimes, problems with the police, even all the way up to the mayor.”

Daniel Friedman recalls: “Caseloads were heavy, detectives were busy, and witnesses were uncooperative.”

A year and a half after arriving, Mueller became homicide chief and began putting in new ideas—from appointing a lawyer to oversee training to running moot courts before every trial.

“He loved being on the ground,” says his colleague Lynn Leibovitz. “His only way of politicking was to be as decent, hard-working, and upstanding as he could be and let the work stand for itself.”

He led a number of high-profile cases, from the Georgetown Starbucks murders to the incident in which a drunk Georgian diplomat killed a teenage girl in a car accident near Dupont Circle.

In the spring of 1998, it was Eric Holder’s turn to make Mueller an offer he couldn’t refuse. Holder was now deputy attorney general under Janet Reno, and the US Attorney’s office in San Francisco—where Mueller had begun two decades earlier—was in turmoil. It needed someone to take over and steady the helm.

Mueller arrived back in San Francisco and began applying his Marine-style management skills. People there were too comfortable, he felt, so he made everyone reapply for his or her job and posted the top criminal-division job nationwide.

Barry Portman, who heads the San Francisco public defender’s office, says Mueller turned back to his Vietnam experience: “It was a good Marine Corps tactic of hit the beach every morning and wake up the troops.”

Mueller felt the staff was working “California hours,” showing up late and taking lunch hours. Mueller ate at his desk.

He turned the office around, making it a model of excellence and innovation. He drilled into local cases, guiding strategy and going back into court in ways that few US Attorneys ever do. The US Attorney’s office and the public defender’s office shared a tradition of buying lunch for whichever side lost a case. Says Portman: “Nobody was buying Bob many lunches.”

One of Mueller’s biggest accomplishments in San Francisco grew out of a feeling that he couldn’t get the data and the details on his attorneys’ cases that he needed. He rebuilt the office’s case-management system from scratch, creating a new program called Alcatraz that eventually was deployed nationwide.

“Bob has this real rare combo of a practical day-to-day manager and a visionary at the same time,” says Beth McGarry, who became his deputy in San Francisco. “Most people are one or the other.”

When George W. Bush took office in January 2001, Mueller was called back to Washington, this time to serve as acting deputy attorney general (DAG)—the person who effectively oversees the day-to-day working of Main Justice and the FBI. Mueller, in his good-natured but firm manner, quickly set the tone. On the Monday after Saturday’s presidential inauguration, when his deputy, David Margolis, showed up at Main Justice, there was an unsigned note on his chair: “It’s 0700. Where are you?” To Margolis, there could be only one author: Mueller.

During his months setting up the Justice Department under Ashcroft, Mueller earned the attorney general’s respect. “When I came into the department,” Ashcroft recalls, “it was already understood that he was someone who was really dedicated to law enforcement.”

After his short stint at Justice, during which he was rumored to have turned down the offer of the permanent DAG slot, Mueller returned to the San Francisco US Attorney’s office. But then Louis Freeh announced he would step down as FBI director. Beth McGarry says she knew the moment she heard Freeh was leaving that Mueller would take the job.

In announcing Mueller’s nomination, the President and attorney general stressed the new challenges for the FBI. But the challenges Mueller would inherit were on a scale no one had imagined.

The FBI had been stumbling in 2001; management problems under Freeh were bubbling to the surface, and morale was low. The capture of FBI agent Robert Hanssen for spying for the Russians had started the year off at a low point. The controversial investigation of scientist Wen Ho Lee was reverberating through the government. Next came a report that the FBI had lost hundreds of weapons and laptop computers. Then, just before Oklahoma City bomber Tim McVeigh was executed, it came out that the bureau hadn’t, as required, turned over thousands of files to the defense—a mistake forcing a delay in the execution.

Mueller looked like a new beginning—the tough law-enforcement professional with a record, forged in Vietnam, of doing well under fire and getting organizations on track. “He had a lot going for him,” then–FBI deputy director Tom Pickard recalls. “There are a lot of synergies between the Marines and the FBI and the US Attorneys and the FBI.”

The Senate confirmed Mueller unanimously. But before he started, Mueller quietly went into the hospital to be treated for prostate cancer. Aides joked that he took nearly four hours off for the operation and recovery; the truth is he was back at work within days. His time in the hospital wasn’t wasted: Pickard prepared thick unclassified briefing books on FBI procedure for Mueller to study in the recovery room.

The unclassified briefing books may have kept him company in the recovery room, but the classified material Mueller began to see and hear was the stuff of nightmares. Everyone knew something was happening in the summer of 2001—something big. Terrorist chatter was high; as former CIA director George Tenet said, “The system was blinking red.”

Tom Pickard recalls, “Everyone was concerned, but no one had many facts.”

The top-secret President’s Daily Brief for August 6, 2001, reported that the “FBI is conducting approximately 70 full-field investigations throughout the U.S. that it considers bin Laden–related.” Counterterrorism officials in government worked overtime trying to figure out what was happening. They never did.

Mueller officially started at the Hoover building on September 4, the same day White House counterterrorism director Richard Clarke tapped out a now-infamous e-mail to national-security adviser Condoleezza Rice accusing the administration of not taking the al Qaeda threat seriously.

Mueller spent that first week as director learning the bureau’s emergency-response plans—what to do in case of a nuclear attack, continuity-of-government plans, and the like. It was standard operating procedure for a new director.

Tuesday morning, September 11, Pickard called the FBI’s New York Field Office after he heard that a plane had hit the World Trade Center. The head of the field office was en route to the scene, so Pickard asked the aide in New York to hold the line open as he reached Mueller, who was in Pickard’s office moments later.

“A plane hit the World Trade Center,” said Pickard, who was watching CNN over Mueller’s shoulder. Then he watched as the TV showed a plane hitting one of the towers. “Look, they’ve already got it on TV,” Pickard said, pointing. A beat or two passed as both men realized they weren’t seeing a replay of the first incident but a second plane and a second attack.

“We’ve got a terrorist incident,” Pickard said. The men raced to the bureau’s Strategic Information and Operations Center, a command post on the fifth floor of the Hoover building. Through the most intense day he would face as director, Mueller never faltered.

“Bob’s a good Marine,” Pickard says. “He was very cool under fire.”

The hours following the September 11 attacks displayed the strengths and weaknesses of the FBI that Mueller was inheriting. By the end of the day, the FBI had a solid picture of the terrorists and thousands of agents across the country were following thousands of leads. Names, addresses, and pictures were pouring in.

At the same time, the technology available to the agents was so antiquated that they had to express-mail photographs of the hijackers around the country because the field offices lacked such basic equipment as photo scanners.

It wasn’t until the afternoon of September 11 that Mueller and Pickard learned that the bureau had been involved in the arrest three weeks earlier of Zacarias Moussaoui, who allegedly had ties to the 9/11 plot. The question of whether that information could, if acted upon earlier, have helped prevent 9/11 would dog the bureau, but it also raised a larger question: How could the vast bureau know what the vast bureau knew? There were so many parts, spread across 56 field offices and dozens of countries.

Just how much 9/11 changed the world was made clear in two scenes the following day. In the first, a secretary brought Pickard—who had spent all summer pushing the Justice Department for more FBI resources to battle terrorism—a letter from John Ashcroft denying Pickard’s request for money to hire additional counterterrorism agents. The letter was dated September 10.

That same morning, September 12, Mueller joined the President, members of the Cabinet, and the National Security Council for a strategy session. They went around the table talking about paths of response and investigation. Then Mueller, who had spent most of his life as a prosecutor, spoke up: “Wait a second—if we do some of these things, it may impair our ability to prosecute.”

Ashcroft responded, “This is different.”

With that simple exchange, 93 years of FBI tradition came to a halt. Since its earliest missions against German agents during World War I, the bureau had developed an arrest culture. It was, many said, the world’s premiere after-the-fact investigation-and-prosecution force.

From now on, prevention would be the focus. “Prosecution is the re-creation of the past,” Ashcroft says today. “Prevention is the anticipation of the future. That’s a much more difficult task.”

Ashcroft explains: “The history of the Department of Justice is prosecution. You deter unwanted activity by prosecuting the offenders. That falls apart when you’re talking about people who kill themselves while committing the act. There’s a Pyrrhic potential for prosecution. It’s an empty threat.”

The message from the President to Mueller was clear: “Never let this happen again.”

The formal announcement of the FBI’s new role would come on November 8, 2001. Within the bureau, Mueller quickly made that new approach clear.

Ashcroft, who had shown so little interest in terrorism that summer, effectively moved his staff and office into the bureau’s operation center, which was now overflowing with more than 500 staff and looked, agents recall, like Grand Central Station. So many people came in and out—prosecutors, agents, and representatives from nearly every wing of the government—that one corner of the complex came to be known as the “mayor’s office.” Its sole job was to keep track of where people were.

In the main secure conference room, Pickard led twice-daily conference calls with all 56 field offices to go over updates on the 9/11 investigation. Pickard slept on the couch in his office; periodically his wife would drop off fresh clothes at the Hoover building.

Mueller was at the office around 5 am and would work until 11 or midnight. Every day he showed up pressed, clean, and ready for more. “I spent more time with Bob during that month than I did my wife,” remembers Michael Chertoff, then head of Justice’s criminal division. Mueller wanted facts. He read everything the bureau could assemble for him.

The pressure was enormous. “Every time the pager went off, every time the phone rang, you thought, ‘We’re moments away from being attacked again,’ ” recalls Chris Wray, then associate deputy attorney general. “You had no idea when or where it was coming.”

The FBI’s operating principle in the weeks after 9/11 became a question: “Are you sure?” Between January and September 10, the bureau’s counterterrorism team had investigated 1,000 terrorist threats; now scores of threats were under active investigation every day, and the President and the Cabinet were hearing about each one. Leads were run down until they could be taken no further, until every question, every avenue was exhausted. Mueller briefed the President each morning. Nobody wanted to be the one responsible for “the next one.”

Then the FBI’s worst fears appeared to start to come true. Reports came in around the country about weaponized anthrax appearing in letters. “We were just starting to have a pretty good handle on 9/11, and then this happened,” Pickard says.

The anthrax case, still publicly unsolved, remains on the minds of many within the FBI. Frustration is evident, but top officials say they’ve made progress they’re not able to discuss.

Mueller’s early days at the FBI were a rude awakening for him. He had been his own boss as US Attorney and prosecutor, and he was used to moving as fast as he wanted. The bureau was different; as people at the FBI lament, “Bureaucracy is literally our middle name.”

At a graduation for new agents at Quantico this spring, the class speaker, new agent Eric Boyce, joked that the training taught the recruits that the bureau has forms for everything and that he had to fill out five of them just to speak at graduation. The remark rang so true that even Mueller’s security detail cracked a smile. Mueller shot back that Boyce was lucky—it used to be 20 forms, but they’d streamlined it.

Despite numerous books written about the Bush administration and the war on terror, few make more than passing mention of Mueller. Few articles have examined his role in the bureau even though he’s the only member of the President’s national-security team still in place from 9/11. He only reluctantly speaks in public or submits to interviews.

His former Justice Department chief of staff Dennis Saylor says, “I can’t think of a greater tribute to his personality than the fact that he’s relatively unknown.” Mueller’s seven years as FBI director recall the description of Robert Lovett, Harry Truman’s Secretary of Defense, described in David Halberstam’s The Best and the Brightest.

“The anonymity was not entirely by chance,” Halberstam wrote in words that capture Mueller’s below-the-radar approach 36 years later, “for he was the embodiment of the public servant—so secure in his job, the value of it, his right to do it, that he does not need to seek publicity, to see his face on the cover of a magazine or on television, to feel reassured. Discretion is better, anonymity is safer: his peers know him, know his role, know that he can get things done.”

People such as CIA director Michael Hayden may figure more in the national news, but it’s Mueller who reports the threats of the world to the President in the Oval Office. The performance of the FBI’s’s 12,000 agents, now serving in 56 field offices and 400 satellite offices around the country as well as in more than 61 nations, will likely determine whether “the next one” happens.

Those in law-enforcement circles understand that Mueller is leading the most significant makeover of the world’s premier law-enforcement-and-intelligence agency. In doing so, Mueller has carved out an independent approach that has at times angered the administration. The bureau’s post-9/11 role has put it into uncomfortable situations, including one in which FBI agents, appalled at what they witnessed during military interrogations of Guantánamo detainees, quietly opened a “war crimes” file to aid in eventual prosecutions. Since its post–J. Edgar Hoover reforms, the FBI has been designed to be free from political pressure and interference.

Although no director has yet stayed for a full ten-year term, that term is meant to outlast whichever President appointed him (and they have all been men thus far). During Richard Nixon’s presidency, senior FBI official W. Mark Felt, appalled at what he found taking place in the administration, became the Watergate source known as Deep Throat.

In the Clinton era, director Louis Freeh had such a sour relationship with the President that the two barely spoke; Freeh turned in his White House pass because he didn’t visit frequently enough.

For Mueller, it all comes down to that oath—the one that all of his agents swore at Quantico when they graduated from the academy. Now, every six weeks or so, Mueller makes the short trip to the FBI Academy to administer that same oath of office to a new crop of FBI agents. Roughly 40 percent of the bureau’s agents are new since 9/11.

It’s said that there’s no such thing as a former Marine, and people around Mueller say he fits the stereotype. Fastidious and serious, he sets high standards and demands excellence. His experiences as a Marine, including Army Ranger jump school and some tough months in combat, forged his personality and style in ways that are reflected daily at the bureau.

“I wouldn’t be here without the Marine Corps,” he says. “You see a lot [in combat], and every day after it is a blessing.” After being in war, he says, “a lot’s going to come your way, but it’s not going to be the same intensity.”

He credits his Marine training with teaching him leadership—although he got a C in delegation in Officer Candidate School. He jokes today that he didn’t understand the concept. “You don’t eat before your troops eat,” he says, “and you don’t ask your troops to do anything you won’t do, too.”

He works his staff hard—chiefs of staff and special assistants rarely last longer than a year with him. His former chief of staff Dan Levin said that when he left, he had worked 365 days straight. Upon departure, they believe in Mueller and his work—he’s a great boss, they say. But they add that they’ve never seen anyone work as hard for as long.

Says Lisa Monaco, his sixth chief of staff in seven years: “He’s got one speed, and it’s pretty relentless.”

Mueller’s small motorcade of iconic black SUVs glides into the Hoover building’s garage each morning shortly after 6 am, making the trip from his Georgetown home quickly in the predawn traffic. On most mornings he has already worked out, something he has done conscientiously since his second knee replacement.

Taken by elevator to the seventh-floor director’s suite, he begins the day by plopping his briefcase onto an empty chair in his chief of staff’s office and asking, “What’s going on?”

The first three hours of his day are spent in threat briefings and investigations followed by a ten-hour whirlwind of meetings and speeches before he goes home around 7 pm.

The FBI director goes to sleep each night with this thought: “Will we be safe until I wake up?” As Joe Persichini, head of the FBI Washington Field Office, says, “I know what keeps me up at night. I can only imagine what keeps him up at night.”

Mueller has been getting better about not working weekends, but there’s always the BlackBerry. “He doesn’t think we’re ever off,” says Don Packham, an assistant FBI director. “We’re always on.”

Mueller takes a few days a year to vacation in Northern California, and one of his rare escapes is a game on a nearby golf course—where he’s often outplayed by his wife. Raised Presbyterian, he tries to attend church regularly; now his preference is Episcopalian. He’s not a regular on the social circuit except amid a group of friends that include people like Georgetown University president Jack DeGioia, former CIA director George Tenet, and Homeland Security chief Michael Chertoff. “He’s not a big ‘Let’s get introspective and unpack our feelings’ kind of guy,” Chertoff says.

Mueller doesn’t socialize much with his FBI staff, continuing a practice that dates back to his earliest days as an assistant US attorney. David Margolis recalls that as head of the criminal division at Justice under George H.W. Bush, Mueller would host a summer barbecue for his section chiefs from 8 to 11 pm. “At five minutes to 11, he’d start flipping the lights to get people out of his house,” Margolis says.

At work, Mueller expects his staff to match his unofficial FBI uniform—dark suits, dark ties, and white shirts. His 7 and 9 am daily staff meetings look like a throwback to the G-men era of J. Edgar Hoover. Colored shirts are worn at one’s own peril. The head of the bureau’s public-affairs division, John Miller—a former ABC investigative reporter who interviewed Osama bin Laden in the 1990s—tries to sneak in a colored shirt on occasion, but Mueller will look down the table at the 9 am staff meeting and ask, “John, what exactly are you wearing?”

Like many law-enforcement officials, Mueller has a dark streak in his humor. During the spring of 2004, when the FBI was tracking Mohammed Junaid Babar, a Pakistani al Qaeda sympathizer, Mueller told deputy attorney general James Comey one morning that Babar, who had been working as a cab driver in New York, had taken a second job. Comey joked that John Kerry was blasting President Bush on the campaign trail for the “jobless economic recovery,” but obviously Babar was having success in his job search.

Later, in the President’s briefing, Mueller set up the joke: “Then Comey said . . . .” The deputy attorney general sat there until President Bush demanded the punch line: “Mr. President, who says you haven’t created any jobs? Babar’s got two new jobs!” Comey made Mueller swear never to set him up like that again.

Mueller’s most cutting joke is to threaten an aide with whom he’s disagreeing with banishment: “You’re going to love Yemen.” According to aides, he has never followed through on the threat, but it does tend to end a conversation.

In White House meetings, Mueller is quiet. He doesn’t feel it’s the FBI’s job to make policy, although he’s quick to correct anything he thinks is inaccurate. Back in the Hoover building, Mueller is much tougher. He’s lacerating to anyone who comes before him unprepared.

Says Lee Rawls: “There was a level of answer that was acceptable within the bureau that didn’t provide the level of detail Bob Mueller required—and objectively probably wasn’t satisfactory, either,”

“It’s like appearing before a smart, tough judge every day,” says Lisa Monaco, a former prosecutor. “He wants to get information—and the right information—and he wants you to be on top of your game.”

As director, Mueller has a decision-making style reminiscent of his training as a prosecutor, executed with the authority of a Marine platoon leader. He gathers as many facts as possible, chews on them, and quickly makes a decision. “His gift is that he’s decisive without being impulsive,” Jim Comey says. “He’ll sit, listen, ask questions, and make a decision. I didn’t realize at the time how rare that is in Washington.”

Once a decision is made, it’s made. In one meeting, Mueller used a line from the submarine thriller Crimson Tide: “I’m here to preserve democracy, not to practice it.”

He isn’t without a soft side. When David Margolis, a longtime friend from the Justice Department, suffered a heart attack in the mid-1990s, he received a handwritten note from Mueller. When Margolis called to thank him, Mueller cautioned, “Don’t be telling anyone about that. It’s bad for the image.”

Colleagues recall one of the “compassionate boss” stories of Mueller’s tenure. Mueller’s wife, Ann, had been warning him that he was working his staff too hard, so he called his then counsel, Chuck Rosenberg.

“How are you doing?” Mueller asked.

“Fine,” Rosenberg said. “What can I get you, boss?”

“Nothing,” Mueller said, and the conversation was over. He could tell his wife he had checked in on his staff.

He has eased up some as the bureau’s position has strengthened and the response to terrorism has matured—threats that once would have been cause for alarm and “orange” alerts are now understood better and measured more accurately.

In the wake of 9/11, the FBI has been handed what many call an impossible task: develop a new domestic intelligence and counterterrorism capability that misses nothing while keeping all of its criminal capabilities first-rate—all without any inconveniences to innocent US citizens, without any profiling, and without any violations of civil rights.

“I don’t believe the job we’ve given Bob Mueller is really doable, so I don’t know how you measure his progress along the way,” says Ben Wittes, a scholar at the Brookings Institution. “One way to look at this would be ‘Who would have done a better job?’ And I think that the answer is ‘No one.’ ”

Most observers of the bureau agree that Mueller has the FBI on the right track even though it might be taking longer than many in and out of government would like to see. “The best argument for the bureau’s future is Bob Mueller,” says Michael Jacobson, who worked on the 9/11 Commission.

Since late 2004, Mueller has grown more confident and secure as FBI director, especially as the furor around the bureau has settled down. One by one—from domestic intelligence to management to computers to National Security Letters to wiretapping—the crises have been addressed.

Mueller’s leadership team is settled. He says that during his first years as FBI director, he struggled to get “ground truth,” to find out “what’s really happening, not just what people want to tell you.”

“The mistakes I’ve made are when I haven’t gotten to the bottom of it,” he says, “dug really deep down, asked all the questions.”

The first three years after 9/11 were a scary and uncertain time for Mueller and the FBI. The bureau’s existence seemed under threat from those who felt it had failed to connect the dots and prevent 9/11. “To a certain extent, the bureau took the brunt of a series of institutional failures that were somewhat broader than the FBI’s failures alone, including by the CIA and others,” says Ben Wittes.

The FBI certainly had many entries in what came to be known around the Hoover building as the “FL,” the “f—ups list,” which included Zacarias Moussaoui, a memo from a Phoenix agent about flight schools, whistleblower Coleen Rowley’s memo, and even two hijackers who had been living under their own names in San Diego.

The reaction of Tom Kean, cochair of the 9/11 Commission, was typical. “It failed and it failed and it failed and it failed,” the Republican former New Jersey governor said at one public hearing. “This is an agency that does not work. It makes you angry. And I don’t know how to fix it.”

Critics wanted to carve out the domestic-intelligence function of the FBI and create a new agency modeled on Britain’s MI5. “The sword was hanging over the FBI,” Comey says. Mueller and other Justice Department leaders argued that the bureau’s law-enforcement responsibilities kept it in touch with the thousands of local police agencies around the country—a key source of intelligence. On the street, criminal and terrorist activities often merge, and many terrorism-related cases are broken because the suspects first appear on the FBI’s criminal-activity radar. The White House signaled that it was open to the idea of dismantling the bureau, and some members of the 9/11 Commission agreed.

His office bookcase reflects the challenges he’s faced: Most of the shelves are devoted to counterterrorism books, manuals on IT and computers, and business books on such topics as “change management” by corporate thinkers like Jack Welch. Only a tiny section is devoted to crime.

In the series of management meetings and briefings that begin each day for the director, there’s frequent laughter, and Mueller—although to admit it might undermine his reputation—actually cracks some jokes himself. He has a hearty laugh, and it’s heard now more frequently in the secure seventh-floor corridor where the bureau’s senior staff operates. He’s more visibly enjoying himself. “He’s had a rough go of it,” says Congressman Mike Rogers, a former FBI agent. “Some of it was brought on by himself, and some of it is the changing mission of the times.”

Mueller pulled out all the stops to keep the FBI intact. While the CIA developed a reputation for making the commission’s life hard and Mueller himself had frequently been at odds with an earlier congressional inquiry on the terror attacks, he gave the 9/11 team space in the Hoover building to go over FBI files and made himself accessible. He showed up at commission briefings elaborately prepared, commissioners recall, with lots of charts and numbers. “The Mueller Show” won them over and, according to staff, signaled a mastery of the Washington game that Mueller hadn’t shown a year earlier in the congressional inquiry.

“He had clearly energized the top leadership,” says Lee Hamilton, the other commission cochair. “The commission was willing to give him time to make changes.”

Some four years later, it seems the commission’s trust was well placed even though the pace of change may not be as fast as some would like. “It’s a work in progress,” Hamilton says. “They’ve got a long way to go.”

At the same time that the 9/11 Commission was breathing down his neck, Mueller was handling the daily terrorism-threat briefings with the President and the drumbeat of al Qaeda. Then, in the spring of 2004, came the greatest crisis of his time as FBI director since 9/11: the internal furor over the National Security Agency’s effort to put into place a mass domestic-wiretapping and data-collection program.

In early 2004, the Justice Department was reviewing a two-year-old program the NSA had dubbed the Terrorist Surveillance Program. While details are still scarce about what exactly it entailed, the program is believed to have been a domestic-focused wiretapping-and-surveillance program unprecedented in scale and scope.

The Justice Department under John Ashcroft told the White House that, upon review, it didn’t believe the program was legal and would refuse to certify it. This meant that the program—which the White House believed was a critical tool in the war on terror—would have to be aborted.

Hours after that uncomfortable conversation, Ashcroft was rushed to George Washington University Hospital with a severe case of pancreatitis. Five days later, he had his gallbladder removed. Jim Comey, who had expressed doubts for months within Justice about the legality of the intelligence coming out of the NSA program in question, became acting attorney general. As the March 11 deadline for recertification bore down, the crisis escalated.

Members of Congress were told of the brewing trouble, and then–White House counsel Alberto Gonzales said he believed the program could continue without Justice’s okay—a move threatening the basic idea that within the nation’s executive branch, the Justice Department’s interpretation of the law was paramount.

Largely unknown outside the government, Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel is supposed to be the government’s chief lawyer, so the idea that the White House would disregard an OLC opinion was a major challenge to the government’s normal way of doing business. Comey and Mueller, both career prosecutors and products of the Justice Department’s way of thinking, found themselves drawn together into the situation.

The exact extent of the program remains classified, and sources familiar with the incident, while refusing to discuss operational details, say only that Mueller played an outsize role because of his reputation within Justice as a straight arrow.

Comey was driving home on Constitution Avenue with his security escort of US marshals the night of Tuesday, March 10, 2004, when he got a call from Ashcroft’s wife: White House chief of staff Andy Card and White House counsel Gonzales were on their way to see Ashcroft in the hospital.

Comey told his driver to turn on the emergency lights and head to the hospital. Then he began calling other Justice officials to rally them at George Washington University Hospital.

Mueller was at dinner with his wife and daughter when he got the call from Comey at 7:20 pm. “I’ll be right there,” he said.

In what had to be one of the strangest phone calls made by any FBI director, he told the FBI agents guarding Ashcroft that Comey and the other Justice officials were not to be removed from the hospital under any circumstances. Gonzales and Card would likely have Secret Service agents with them, and the bureau was to prevent any interference from them.

Imagine the moment: the FBI director ordering his agents to use force, if necessary, to prevent the Secret Service and White House from removing Justice Department officials from a hospital room.

Motorcades and officials converged on the hospital. Comey beat Card and Gonzales to GW hospital and ran up the stairs. The White House pair arrived minutes later and went to Ashcroft’s bedside, ignoring Comey and the other officials.

Ashcroft fought off the White House demands, telling Card and Gonzales why he wouldn’t sign off on the program. He finished by pointing to Comey: “But that doesn’t matter because I’m not the Attorney General. There is the Attorney General.” Jack Goldsmith said later that it was such an amazing scene that he worried Ashcroft would die on the spot.

Card and Gonzales left, saying only, “Be well.”

Mueller arrived at the hospital moments after the White House aides left. He talked with Comey in the hallway and then entered Ashcroft’s hospital room. “Bob,” Ashcroft said, “I don’t know what’s happening.”

Mueller said, “There comes a time in every man’s life when he is tested, and you passed your test tonight.”

Then came a phone call from Card summoning Comey to the White House. Comey refused to go without a witness, Solicitor General Ted Olson.

Mueller left the FBI detail with instructions that no one was to be allowed to see Ashcroft without Comey’s consent.

The next day, terrorists struck Madrid—exploding bombs on trains during the morning rush hour and sending the Homeland Security apparatus into high alert. At the same time, Mueller, Comey, and most of the senior leadership of Justice and the FBI were preparing to resign when a call came from Ashcroft’s chief of staff with a plea: The Attorney General isn’t well enough to join you in resigning yet, and he can’t be left hanging alone; hold on until Monday, when he can join you.

That delay, which gave both sides of the battle enough time to resolve their differences, was the only thing that stopped what would have been one of the most explosive Washington confrontations in recent memory: There would have been huge political implications if Justice and FBI leadership had resigned en masse in the middle of a presidential campaign to protest an unconstitutional policy.

“No President wants the director of the FBI to resign. That’s the ultimate H-bomb,” Dick Thornburgh says, adding that as far as Mueller is concerned, his principles—his oath to protect the Constitution—are paramount. “People are smart not to test him on those issues.”

After the terrorism briefing on March 12, the President met privately with Comey and then with Mueller. Comey explained his thinking, and Mueller explained in the second meeting what he thought was needed to make the program legal. President Bush handed down his order: “Do what the department thinks is right.”

Mueller spent much of the next days on the wiretapping-and-surveillance program, serving as an emissary among the various parties. He met privately with CIA director George Tenet in the White House Situation Room the following week. As one colleague said, “His view was ‘I can’t stay and have the bureau involved in a program that’s not certified to its lawfulness.’ ” In the end, the White House caved.

When the crisis was over, Comey and Mueller shared a dark laugh. “This was easy,” they said to each other.

When news of the bizarre night leaked last summer and Comey testified before Congress about what had happened, Congress asked Mueller for his notes from that night. He released a detailed but heavily redacted timeline showing some 23 meetings in March on the subject, including ones involving Vice President Cheney and General Michael Hayden. They recorded that Mueller felt the Attorney General was “feeble, barely articulate, and clearly stressed.”

When pressed by Congress after Comey’s testimony, Mueller admitted only that the visit to the hospital was “out of the ordinary.” But behind the scenes, he had taken his oath to protect the Constitution from all enemies, foreign and domestic, seriously. He’d done what he needed to do.

Asked about the hospital visit today, Mueller waves it off, saying, “That’s not difficult.” He adds, “It’s not that it doesn’t keep you up at night, but once you chart a course, you just do the right thing.”

The FBI, Mueller believes, is the government’s honest broker—an agency free of political interference and pressure, priding itself on objectivity and independence. “You’re free to do what you think is right,” he says. “It’s much easier than if you have to consider the political currents.”

Mueller’s father, who was captain of a World War II Navy sub chaser, impressed on his son the importance of credibility and integrity. “You did not shade or even consider shading with him,” Mueller says. “The most devastating thing that can happen to an institution is that people begin to shade and dissemble.”

To the former prosecutor and Marine, aides say, matters of honor and principle are black and white. “Occasionally he’ll be a pain in the ass because he’s so strait-laced,” Lee Rawls says.

Larry Thompson, deputy attorney general under Ashcroft, says, “When he has a point of view, you know it’s held honestly and openly. There’s no subterranean agenda.” In discussions, Mueller is perhaps the only person in Washington who offers “yes” and “no” answers to questions. No caveats, no punches pulled, no “Yes, but . . . .” Mueller sees black or white.

Throughout his tenure, the war on terror has tested Mueller’s moral courage and management skills. The hospital incident—coupled that summer with the final report from the 9/11 Commission that recommended keeping the FBI intact—helped mark a turning point for Mueller and his stewardship. He had spent much of his first three years as director struggling to get his arms around the FBI’s massive bureaucracy and unique culture while simultaneously leading the 9/11 investigation and defending the bureau.

Toward the end of 2004, the FBI was beginning to gel. Mueller’s leadership team was stabilizing, and issues such as National Security Letters and the FBI’s approach to the “enhanced interrogations” under way at Guantánamo Bay began to be addressed. Agents finally began to get some technology. Things were beginning to hum.

Next month: How Robert Mueller and the FBI are coping with the growing globalization of crime and terror—from National Security Letters here in the United States to interrogating al Qaeda detainees in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Guantánamo Bay—as questions are raised about whether the bureau has gone too far too fast and whether it has the tools it needs to succeed.

Have something to say about this article? Send your comment to editorial@washingtonian.com and it could appear in our next issue.

This article first appeared in the August 2008 issue of Washingtonian.