It is the unthinkable, every parent’s nightmare, the world turned upside down. The death of a child plunges you into a parallel universe of loss where the old assumptions about everyday life–that a spouse going to the store for milk will return, that a teenager headed off to school will still be alive when school lets out, that a child put down for a nap will wake–no longer obtain.

You can’t stay in this place, of course. Your new knowledge is too hard to bear. Eventually, after much despair and grief, most of us claw our way back to normal lives. We learn to suppress some of what we know to keep going. But we never forget, and we’re never the same.

For the rest of our days, an arbitrary date cuts our lives into “before” and “after.” For me, that date is June 16, 1999.

***

AFTER THE PLANE REACHED THE GATE AND THE captain turned off the seat-belt sign, a flight attendant came on the intercom and said, “Mr. William Heavey, please see the gate agent for a message.”

I was impressed. Jane had said she would try to pick me up at the airport when I returned from a conference, but she didn’t know if she’d be able to get the baby from daycare in time to make it. I figured she’d persuaded someone at the airline to have me paged with the news that I should get a cab home.

When I introduced myself to the woman with the clipboard, she said, “Follow me, please.” After four days of meetings and hotel food, I didn’t want to follow anybody; I just wanted to get my damn message and see Jane and Lily. When I asked her what it was, she glanced back over her shoulder and said, “I don’t know.”

She opened a locked door to a cement stairwell and began to lead me down. After the first flight of stairs a beefy guy fell in two steps behind me. He was wearing small gold insignia on the shoulders of his white shirt. I thought I caught a glimpse of a badge. I glanced back, and he nodded, his eyes noncommittal.

We went through another door to what seemed like a secure area with a series of small offices. He began poking his head into one after the other, looking for an empty office. At last he said, “Could you give us a minute here?” to the guy inside one.

The man led me into the tiny space, motioned me into a wooden chair, and shut the door. I was scared. I hadn’t committed any crimes, but this was not where they took you for good-citizenship awards. I still can’t remember what he looked like, though I realize now I was staring him in the face the whole time.

He told me a name and said he was with the Arlington fire department. Sometime that afternoon at daycare, my daughter had gone into cardiac arrest. An ambulance had rushed her to Arlington Hospital. The doctors had done all they could, but they couldn’t get her heart started again. Lily, my baby girl, the perfectly healthy child we had adopted just ten weeks before, was dead. My wife and stepdaughter, Molly, were at the hospital. The man would drive me there. Someone would collect my luggage and take it home.

***

JANE AND I WERE IN OUR FORTIES WHEN WE MET IN 1995. Like most single men of that age, I had definite ideas about what I wanted: someone a few years younger, never married, certainly without a child. Then I met Jane, who was none of these things. But she was beautiful, hardheaded, honest, and scrappy. I fell in love and gave Jane the ring that my great-grandmother had bought in Paris in 1901.

Molly–then nine–was part of the package: a bright, affectionate girl with dark hair and her mother’s will. I fell in love with Molly, too. Two years later, she was the flower girl at our wedding. When Jane and I watched from the altar as Molly walked down the aisle of the Bethlehem Chapel in the National Cathedral, smiling at friends and family on both sides, we marveled at how luminous she looked. Jane and her ex, John, have worked hard to have a good divorce and remain friends. Molly sees both of them nearly every day and spends half her nights at his house and half with us. I love Molly like a daughter, but she already has a dad, and the two are immensely loyal to each other. Besides, I wanted the full platter of fatherhood–baby giggles, a tiny fist tight around my little finger, baby puke on my shirt, the sound of “da-da” spoken for the first time.

Like many parents who eventually adopt, Jane and I first spent a couple of years and tens of thousands of dollars trying to have our own biological child. We’d traipsed through the well-appointed offices of cheerful area specialists who rattled off success rates for various procedures as if handicapping hedge funds. I’d learned to make love to plastic cups under the fluorescent lights of clinic bathrooms so my sperm could be clocked for speed and endurance in the 40-micron dash. I’d jabbed needles dripping hormones into my wife’s purple-bruised backside every night for a month on three occasions to ready her womb to receive an egg fertilized in a petri dish.

A guy so cheap that he haggles with the ladies at Goodwill over shirt prices, I’d willingly written the biggest checks of my life outside of buying a house in hopes of fathering a child. The doctor had told us the odds of Jane’s getting pregnant with in-vitro fertilization were 43 percent. I’m not a gambling man: I look at a casino and see a well-oiled machine founded on human weakness that separates people from their money the way Eli Whitney’s cotton gin separated cotton from seeds. But when it came to my dream of fatherhood, I was a willing mark. I thought that Jane and I were somehow special, different–that we’d beat the odds.

Well, we weren’t. We didn’t. When the first transfer failed to take, I burst into tears on getting the news. After the second, hardened by disappointment, I’d shrugged. After the third, the doctor called us in for a consult. “It’s unusual,” he mused. “You should have gotten pregnant by now.” It was an abstract problem for him, an equation that should have worked out. He pointed out that we could try again. But the drugs were an emotional roller coaster for Jane, each failure added another layer of despair, and I was running out of money. It was his detachment that I resented the most. Standing in his office with the framed photos of babies and testimonial letters, I imagined pushing his stylish little eyeglasses down his throat.

***

IN THE FIREFIGHTER’S CAR, I WAS VAGUELY AWARE OF THE highway rolling by and the hazy June light outside. The road was jammed with people jockeying for position as if it were just another day. I heard the man’s voice saying something about how he’d talked to the people at the hospital and heard that my wife, like me, was bearing up.

An involuntary hoot of laughter started to rise in my throat. I wasn’t bearing up; I was disappearing. This was happening to my stand-in, my stunt double. I had gone off some distance to watch. I noticed tears and that my vision seemed to be collapsing around the edges. I thought I might keep the world from dissolving entirely by focusing on its navel, which at the moment happened to be the glove-compartment latch two feet away. Lily, the child who cooed in delight when I slung her round my shoulders and twirled and sang her nonsense songs in the dining room, was dead. Tomorrow she would have been four months old. Say the magic word and a baby appears. Say it again and–poof!–she’s gone. It couldn’t be true. It was true.

A statistic I wasn’t aware I knew popped into my head: More than three-quarters of marriages in which a child dies do not survive. It occurred to me that in one stroke I might have lost not only Lily but Jane and Molly as well.

Jane and I had long talked about adoption as our backup plan if the fertility efforts failed. We’d done some research and decided that we preferred a private, domestic adoption rather than going through an agency or adopting from overseas. We didn’t like the idea of seeing a photo, taking a trip to China or Korea, and then having to decide yes or no on the spot. We wanted to meet the mother, get to know her, make sure it felt right. It was more work and would probably take more time than an agency adoption, but it offered more control. At that point, we were big on control.

We got involved with a local group, Families for Private Adoption, which offered advice and support. One of the first things we learned was that everyone you know or meet is a potential lead: friends, family, the checkout clerk at the grocery store, the attendant at your health club, people at parties. “Get over being self-conscious,” one woman who had adopted three children told us. “You’re on a mission. Do at least one thing every day. Post a card on a new bulletin board, research a new place to run an ad, buttonhole a stranger. Most people are happy to help. If they’re not, that’s their problem.”

You give every contact at least one business-size card with your pitch. The guideline about the pitch is the simpler the better. We pared away the language on our card until it was bare bones: “A very warm, loving couple unable to have second child seeks newborn to love and nurture. Can pay medical, legal expenses.”

You also have a separate, unlisted, toll-free line installed to receive calls. The fact that it’s separate means you can leave a message on the answering machine specifically for prospective mothers. The toll-free part means a woman never has to speak to an operator to place a collect call. “You want to make it as easy for a mother to contact you as you possibly can,” we were told. And an unlisted number makes it that much harder for scam artists to locate you. (People desperate to adopt are notoriously easy marks.)

We passed out cards. We ran ads in newspapers all over rural Virginia. Adoptive parents soon discover that a baby is a commodity, subject to the laws of supply and demand. In metropolitan Washington, with a high number of career women who sometimes wait too long to have children, the demand for babies is high and the supply is low. In southern Virginia, the situation tends to be reversed.

We checked the message machine every time we walked in the door. Months dragged by. Nothing happened. We had been warned about this. We knew that all it takes is one phone call. “If you stick with it long enough, you will find a baby,” we’d been told again and again.

When we finally got lucky after five months, it was via the typically circuitous route that domestic adoptions often take. Our neighbors next door, Kevin and Ellen Bailey, had heard through several layers of chance encounters of a Vietnamese woman who worked as a manicurist and might be putting a baby up for adoption.

Were we interested? Absolutely.

***

THE FIREFIGHTER’S CAR CAME TO A STOP. SOMEONE opened my door. Inside the emergency room was a clot of people. In the middle were Jane and Molly, wild-eyed, their faces flushed and streaked with tears. The three of us ran and clutched at each other, the sobs at last finding their way up into my throat. Nurses shepherded us into a private room.

Jane had been there for more than an hour and had already done the unthinkable, gone in to see Lily’s body. She had pleaded with the nurses not to take Lily to the morgue before I got there. A nurse came in to talk to us. She said that Hien, the woman who ran our daycare center, told them she had put Lily down for a nap, then checked on her after 90 minutes to find her blue-lipped and still. She tried CPR, then called 911. Paramedics worked on Lily in the ambulance. At the hospital they worked on her some more, but she’d probably been dead when she arrived. It sounded to the nurse like sudden infant death syndrome, SIDS, also known as crib death.

Doctors don’t know why, but each year about 1 in 1,400 babies in the United States, most between one month and one year old, stop breathing and die. There is no telltale sound, no warning, no sign of a struggle. The nurse told me I could see Lily, though she warned I might not want to, as they’d had to stick tubes down her throat and in her leg. In a voice so enraged I could barely control it, I bit off the words: I will see my daughter.

Jane and I held each other as a nurse led us into an examining room cluttered with medical equipment. In one corner, a uniformed cop stood absently, as if a bus he wanted to catch might be passing through soon. My daughter lay swaddled in a blanket on a table, wearing only a diaper. The tubes were there, but otherwise Lily was unblemished. “She was warm before,” said Jane, stroking her cheek. “She’s–cold now.”

I picked Lily up, felt her smooth baby skin, cradled her head in my neck. I recognized everything about her: her small heft, her black hair, her brow, her cheeks. But this was not Lily; this was the doll that death had left behind. Her cheek was cold against mine. I couldn’t seem to breathe. My vision started to go again, the sides of the room caving in. “She’s–so–cold,” I finally managed to say.

The police officer shifted on his feet. What was he doing here? Then it dawned on me that someone might suspect us of having killed our own child. As long as the world had turned into hell, why not throw in a murder charge? I started to dissociate again, to feel like I had a part in some strange play. But the fact of her body in my arms was too real. Then I felt a tiny bit of warmth in her back, the last spark of life that was even now on its way out of her body, this room, this earth. “Still–warm!” I blurted out to Jane. “I know,” she wept. “There was more before.” I held Lily tight and rocked, long swings forward and back as if I might somehow wake her. I was numb now. What would happen when the numbness wore off? The nurse came in and put a hand on my shoulder. I understood the signal. I was a good boy. I obeyed.

***

WE HAD MET LAN (NOT HER REAL NAME) on a Wednesday morning at her friend’s house over cups of mint tea. She was in her early twenties, with a round face, shoulder-length black hair, and, of course, impeccable nails. Our first impression–of a reserved, serious young woman–was just the armor she wore until she felt comfortable. Underneath, she was a strong-willed girl who liked to laugh. She was unmarried, worked 70 hours a week at a salon in DC, already had two toddlers, and had just had another baby. We liked Lan right off the bat.

She hadn’t brought the baby but had brought along one of her other children, a four-year-old boy. He was happy and well cared for. When I shook his hand and kept shaking it as though he were the one who wouldn’t let go, he giggled.

Lan had come to America in her early teens from South Vietnam, dropped out of high school when she got pregnant the first time, and had been working full-time ever since. Her parents were divorced, her siblings scattered all over the country. She was on her own. “It just too much,” she said. “I can’t take care three children.”

We stayed for an hour, drinking tea and making small talk. We showed her pictures of Molly and of our house, and the Christmas card at the animal shelter with the three of us standing around Santa’s sleigh and Snoop, our adopted dog, looking forlorn in a red stocking cap with a snowball on the end.

We said we would love to meet the baby. She told us to come to her apartment in DC on Sunday, her day off.

The next Sunday was Easter. Jane, Molly, and I drove into DC, stopping at a bakery in Adams Morgan for a cake in the shape of an Easter bunny with white coconut fur. Lan lived in a tiny apartment in a building apparently occupied mostly by Vietnamese. Lying in a baby carrier and wrapped up so that all we could see was her face lay a six-week-old baby girl with black hair and brown eyes.

We sat on Lan’s bed and fed cake to her son and other daughter, a two-year-old who found Molly fascinating. Jane and I took turns holding the baby, whom Lan had named Stephanie. She was small but solid and seemed remarkably self-contained, as if accustomed to spending time on her own. Lan had a boyfriend upstairs, whose mother lived with him or in the unit next door; we never did decipher which. The mother took care of all three children while Lan worked.

As I held her I wondered, Are you the one? How will we know? Jane was smitten instantly. “Oh, she’s so charming,” she told Lan. “She’s beautiful.” I looked at Jane’s face. It was glowing with the look of a woman who had already begun bonding with her daughter, a process that bypasses the brain entirely. That was how we knew.

Lan told us to wrap Stephanie tightly and not to hold her too much. “She smell you,” Lan said. “Then you can’t put her down easy.” We nodded. We didn’t say that having the baby smell us, bond with us, and demand to be held was exactly what we wanted. Lan’s face never changed, but tears began to run down her cheeks. “You good people,” she said. “You take her.” Jane and I exchanged glances. We had discussed that we might be coming home with a baby today, had even hauled Molly’s old crib out of the attic. Suddenly, it was actually happening.

Lan insisted on loading us up with diapers, formula, clothes, a car carrier, and a few toys. She refused money for these things. We explained about how the adoption process worked, that we would get her an attorney as well as a social worker who spoke Vietnamese to do the required counseling, and that eventually she would go to court with us in Virginia to make the adoption final. We told her that she could visit anytime, that we wanted the child to have the opportunity to know her biological mother when she was older if she wanted.

Lan’s face was losing its composure. “Please,” she whispered. “Take her now.” Suddenly we were on the sidewalk blinking in the bright sunshine of Easter morning with a baby in our arms, feeling a strange mixture of elation at our good luck and sorrow for the loss Lan was going through. It was as close to instant fatherhood as a man could get.

***

IHAD TOLD MY SISTER, OLIVIA, ABOUT the possibility of getting a baby, but not my parents. They’d already had three rides on the fertility roller coaster with us, and I wanted to spare them more disappointment. My mother had never said anything, but it was obvious she wanted nothing on earth so much as a grandchild.

We were due to have lunch with them and a family friend that day at the hotel where Olivia worked, and we intended to surprise them with the good news. But our plans were foiled when Jane went into the ladies’ room to change the baby before our triumphal entrance and ran smack into my mother. Baby, mother, and grandmother proceeded into the dining room, where the baby was officially welcomed into the family with laughter, tears, and Champagne. Olivia took the baby back to the kitchen to meet the staff. Photos of the occasion show me looking like a man who has just been hit in the face with a frying pan. We had already decided on a name. Elizabeth, after my mother. Ashley, Jane’s maiden name, for her middle name. And Heavey.

I wish I could say she came home with us and fell sound asleep. In fact she was up all night, crying. “I think she’s terrified,” said Jane. “She doesn’t know why she’s here or who we are.” Jane stayed up all night with her, walking her in the living room and massaging her back as she lay sobbing in her crib. I opted for the only constructive thing I could think of, a massive anxiety attack. Staring at the ceiling in bed, I wondered if we had done the right thing, whether I was ready for this, what business I had accepting another woman’s child to raise. I called a good friend on the West Coast who had also adopted. “I’m just freaking out,” I said. “I’m so anxious I can’t think straight.” “Enjoy it while you can, pal,” he laughed. “Soon you’re gonna be too busy to freak out.”

We got through that night. And the next, and the next. My friend was right. I learned to change a diaper one-handed while pinning a squirming child to the changing table with the other. To heat a four-ounce bottle precisely 27 seconds in our microwave. To transfer the napping baby from my arms to her crib with the dexterity of a bomb-disposal technician. I learned to sing lullabies I didn’t know I remembered as I stroked her stomach to put her back to sleep after a feeding in the middle of the night. Some nights I would linger, watching over her and listening to her breathing.

She began to smile when I approached her crib or picked her up. “It’s Daddy,” I would say as I tucked her up in the hollow of my shoulder. “How’s my girl today?” She especially loved it when I stretched her arms and legs on the changing table, yoga-style. She was yielding but quite strong, and the harder I tugged, the more she smiled. Sometimes she would gurgle in delight. “Little Buddha girl,” I cooed at her. “The perfect being.” The happy sounds she made seemed as close to pure joy as humans are permitted. I was becoming a father. I was learning what all adoptive parents know: It’s not DNA that confers paternity. It’s baby poop.

We always called her “the baby” until we took her for a visit to my father’s mother, Granny, 99 years old and living in a rest home on the Eastern Shore. “Elizabeth,” mused Granny, when we told her the name. “You know, Queen Elizabeth was called Lily when she was a girl because she couldn’t pronounce her own name. She could only say ‘Lilybeth.’ ” Jane and I looked at each other. Lily. That was the name we’d been looking for. Thereafter the baby was Elizabeth on legal documents but Lily for all other purposes.

Jane and I had worked out an arrangement for baby care. Because my wife sees clients at her psychotherapy practice mostly in the afternoon, she would take the baby in the mornings, leaving me free to write. In the afternoons, we would switch. In the evenings, we would share duty.

For reasons I cannot now fathom, I expected to be a natural at baby care. Jane said I was better at it than most men, but she said this in the same way you might note that horses are better at needlepoint than most fish. I knew only three things to do with a crying baby: feed it, change it, or burp it. If none of these worked, I repeated the sequence until overwhelmed by anxiety, frustration, and crankiness, not unlike Lily herself.

Jane, having already raised one child and coming from a large family overflowing with nieces and nephews, had not only more experience but another quality I seemed to lack: baby intuition. She could tell what Lily wanted just by looking at her, a feat bordering on witchcraft. “She wants water, not formula,” she would say, based on a look. Or that the baby would stop crying if I (a) took her for a walk, (b) put her on her stomach, or (c) sang the theme from The Sound of Music.

The arrangement was supposed to be 50-50 but wasn’t. Jane ended up doing far more than her share. It was the source of more than a little friction in our marriage. Three hours alone with the baby would leave me exhausted. “You don’t get it,” Jane would say. “You have to surrender to her.” I come from five generations of career military. My father was a fighter pilot. Surrender was not in the curriculum.

Because I occasionally have to travel for work, we figured we’d need extra help now and then. We turned to a Vietnamese woman who offered daycare in her home nearby and came highly recommended by dozens of parents in the area. We inspected her house one afternoon. It was clean and bright. Hien picked Lily up, and the baby beamed at her. We told Hien we would be irregular clients, and she said that would be fine. She asked us to give her a couple days’ notice because she took only one or two infants at a time.

***

WHEN WE GOT HOME FROM Arlington Hospital, I began the grim job of notifying family and friends. I would compose myself to make the call, but the moment it went through–even to an answering machine–I fell apart. I can’t remember most of the calls. I know I talked to my mother and left messages for several friends, including the friend who had adopted. There weren’t that many people it felt right to tell. My friend got the message on his car phone while driving. At first he thought it was a terrible joke. Then he pulled onto the shoulder, listened again, and broke down crying.

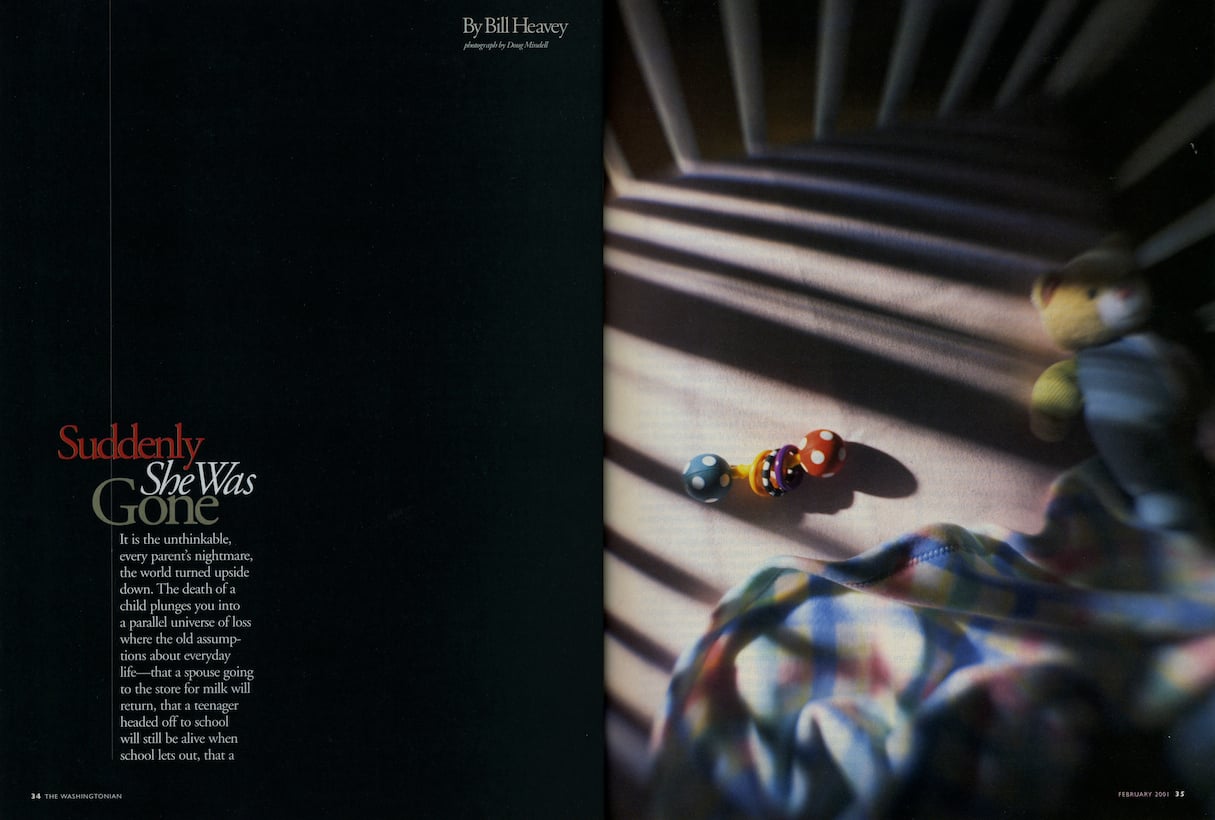

The bottle Lily had used that morning was lying unwashed in the sink when we got home. Her clothes were on the floor and the changing table. Her favorite toy, a cloth butterfly with big red wings with mirrors in them and long blue antennae, lay in her crib. I pressed my face into the mattress and smelled the baby smell lingering in the sheets. I fell to my knees, clutching at the bars of the crib. She was dead all over again. It was still happening.

My parents and Olivia came over. Friends of Jane’s came by. Around eight o’clock, it occurred to me that while family members were embracing one another and saying that we would get through this somehow, my daughter was alone and lying on a stainless-steel table in the morgue. I wanted to be with her, to watch over her one last time. I made frantic calls to the emergency room and was refused at every turn. It was, I was told, impossible. Once again, I obeyed.

Months later, in a SIDS support group, I met a single mother who had experienced the same feelings, made the same phone calls. Only she wouldn’t take no for an answer. She had gone and sat on the steps of the morgue and refused to leave. She hadn’t been let in. But she had made the attempt, had made the people who told her no look her in the eye. I was filled with admiration for her tenacity. And I will always regret that I didn’t find out exactly where my baby was, go down there, and beat at the door until they let me in to sit by Lily or had me arrested for trespassing.

There was one more call to make. Lan had to be told. I reached her at about ten o’clock. She seemed happy to hear from me. “How’s the baby?” she asked brightly. “Lan, I have bad news,” I said. I told her to sit down. I told her just as the firefighter had told me: Lily had stopped breathing at daycare, an ambulance had been called, the doctors had worked on her, that she had died. I heard gasping for breath on the other end of the line. “Lan, is anybody there with you? Any friends?” She said there weren’t. I asked if she wanted me to come down. Five minutes later, I was headed her way.

I stayed for the better part of an hour in her tiny apartment with the two children lying on the bed. She didn’t let them know what had happened. She left the door open, and people from the building came and went in the hall, talking among themselves in Vietnamese but not coming in. I had no idea what they were saying, but I could imagine it well enough: You see. Give your baby to one of them and it dies.

I tried to comfort Lan, telling her that Lily hadn’t suffered, that no one understood why some babies simply stopped breathing in their sleep and died. After about an hour, I found myself out on the same sidewalk as on Easter morning. It was after midnight. There were knots of people moving about in the shadows, cars cruising slowly by. I drove back to Arlington. Molly had gone to sleep. Jane and I held each other and took turns crying. I drank rum and tonic until I couldn’t stay awake any longer.

Early the next morning, Olivia called. “Everything’s okay, but Mom and Dad’s house burned down this morning,” she said. “I didn’t want you to hear it on the television news.” I realize now that she had chosen her tone carefully, the way you do with people in shock so as not to upset them further. The house my parents had lived in for 35 years was mostly cinders? Most of what they owned up in smoke? No big deal. At least they weren’t dead.

I found out later that a passing newspaper carrier had seen the fire, which apparently started from faulty wiring in the basement that took decades to burn through its insulation–and just happened to finish the job about 14 hours after Lily’s death. The man had thrown rocks at the bedroom window, waking my father and almost certainly saving my parents’ lives. Initially, too stunned to take in new information, I accepted the destruction of the house I’d grown up in as a distraction, sort of like losing your credit cards. A baby’s death, a house fire the same night. The surreal was becoming commonplace. These things are supposed to run in threes, I thought. What was next?

Flowers began to arrive. The phone rang as the news about Lily spread. Then the police showed up. The Arlington detective asked if he could come in, then told us that Hien, the woman running the daycare where Lily died, had had 36 children in her home. Thirty-one children were in the basement; four infants were in the room with Lily. She was licensed for no more than five children.

“These people, they come over here and get used to nice things,” the detective said. “Sometimes, they get greedy.”

Police had raided her house–removing even her son’s computer to look for evidence–and yanked her license and shut her down. She was being charged with violating state licensing rules and taking money under false pretenses. There might be more charges later.

Hien had lied to us. She’d told us she never took more than two infants, and there were five in that room, plus all the kids downstairs. Jane and I had never asked Hien exactly how many kids she took care of, a ludicrously obvious question in hindsight. It flashed through my mind that her neglect might have led to Lily’s death. But if she was guilty of neglect, then so were we for having hired her. And it seemed like the cops were out to get her, in no small part simply because she was Vietnamese. I was angry at Hien for lying, the police for their attitude, myself for trusting her so readily.

The detective told us that although Hien had too many kids for her license, she did have the proper number of helpers. He asked some follow-up questions, told us he’d be in touch, and left. After he was gone, Jane was quick to defend Hien. I was less convinced. She had lied to us about the number of infants she took in. What else might she be lying about?

***

THE FUNERAL WAS ON SATURDAY, three days after Lily’s death, at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Arlington. I put aside my lifelong fear of speaking in public to bid my daughter goodbye but didn’t know how to say it. I was raised Episcopalian, but Jesus and I are still looking for each other. Instead, I turned to my yoga teacher, Victor, who runs Shanti Yoga in Bethesda. Over the past ten years, I’d taken lessons off and on and come to regard him as a sort of unaccredited holy man.

When I called, he said he would write something that I could adapt as I saw fit. I don’t know that I believe Victor’s take on the cosmos any more than the Church’s, but I trust him. Standing before the crowd and trying to breathe, I knew I would break down as soon as I started talking. But I no longer cared. I unfolded my notes and read my teacher’s words:

“Lily didn’t stay long on this earth. Certain beings need only a brief time here to complete their work before moving on to a higher place, a place from which they will both continue their own journey upward and help those who stay behind. I believe that Lily was, and is, such a soul.

“The relationship that Lily formed with those who loved her is an ongoing one. Those bonds of love created a channel of communication that never closes. I believe the departed soul of this child is making a great effort to soothe the pain of those left behind. Her compassion compels her to stay close to those who loved her so strongly and to help them through this time. The compassion of such souls is so great that they will do this even if it means inhibiting their own soul’s upward journey.

“Let us return her sacrifice by releasing her spirit and not hindering her journey with our suffering. Let us draw on our courage and faith in God to overcome our pain. I ask us all to take a moment to open our hearts and imagine Lily’s soul entering the holy assembly of spirits, those beings who vibrate with a love so pure as to be inaccessible to human experience. Let us give thanks to her and all those involved in her time on earth for allowing us to partake in her miraculous journey.”

Jane spoke. Molly spoke. A minister spoke. Two hundred people, more than I had ever imagined would show up, stood in silence as a violinist played “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.” It was a beautiful moment, the instrument’s clear tones ringing through the church, the melody searching for a way up and out of this world. I had thought I was all cried out. The violin found a whole new reservoir of tears.

***

IN THE DAYS AND WEEKS AFTER LILY’S death, Jane and I paced mechanically through our lives, stopping several times a day to cry, while Lily’s ashes, amounting to a single handful, rested in a blue urn on the mantle. Jane seemed more tortured by doubts and “if onlys” than I was, turning over in her mind all the things that we might have done differently: kept the baby at home until she was older even if it meant going into debt, hiring someone to come to the house instead of taking Lily to daycare. It’s hard to elude the belief that you might have saved your child if you’d been there.

For whatever reason, I escaped the worst of this cycle of second-guessing. The separation had been so swift, random, and horrifying that it seemed–at least in the way insurance companies use the term–an act of God. To apportion blame or to wonder what might have been done differently supposed a rational universe, a place where there were reasons for Lily’s death. But making sense is not among the universe’s higher priorities. Its workings are hidden, perhaps random, and Lord help you if you get in its way.

I imagined Lily’s short life as a plane coming in for a landing on an aircraft carrier in rough seas. My father had often told me that when a pilot sets his craft down for a carrier landing and finds that he’s not going to make it, his best option is to power up, take off again, and circle around for another attempt. Maybe that’s what Lily had done–flown down to earth for a landing and taken off again just as we thought she’d come to rest in our arms. Maybe she was up there right now looking for a safe place to land. I didn’t believe it, but it was comforting to imagine it that way.

Life went on. The paper landed on the lawn every morning, the dog still hurled herself at the front door when the mail lady came, the shouts of the kids at the Catholic school across the street still penetrated our walls. I realized that just as the world was oblivious to my loss, so had I been oblivious to others’ losses until Lily’s death. How many faces had I passed on the street who were inwardly unmoored by the recent loss of a child, wife, or husband? They had always been there, peering back at me from that parallel universe of loss. I just hadn’t seen them. And now I was one of them. Every morning I woke and moved once more through my own life like a ghost.

I went fishing a lot that summer. I would drive up to Violet’s Lock on the C&O Canal out past Potomac and wade the river with a spinning rod for smallmouth bass. My hands were practiced at the motions–tying on a lure, casting, retrieving–and I was content to let them work. Wading deep into the water, I fished in hundred-degree heat and in lightning storms, half hoping that a stray bolt would arc down my graphite fishing rod. Whenever I caught a fish, bringing it up into the world of air before releasing it, I wondered if this was what dying was like, passing from a world where you could breathe to one you couldn’t.

Or maybe death was the discovery that you finally could breathe there after all. What was life that made it different from death? What slender thing separated the lively baby I’d known from the doll in the emergency room? It did seem that her tiny spark must live on somehow, that matter may be changed but not destroyed. Maybe it had been absorbed into one of the lightning bolts I was half wishing would come my way.

Out on the river, I began to talk to Lily. I told her how much I missed her and loved her and that I hoped she was safe. That I would always be with her. I felt the water sliding past my legs. At dusk, birds came out to wheel and loop in the heavy air to catch insects. No lightning came near me that summer.

***

JANE AND I NEVER RESOLVED OUR difference about Hien. For whatever reason, Jane forgave her totally and almost instantly. She said that Hien was nearly as devastated by the loss as we were, that she had complied with the spirit–if not the letter–of the law by having the proper number of helpers, and that a zealous Arlington prosecutor might well want to make an example out of her. She pointed out that Lily might just as easily have died in our own home, in which case she and I would be blaming each other.

All of this was true. But I felt that Hien had misled us, if not lied outright. And I couldn’t get past the fact that we had entrusted our daughter to her care and Lily had died in that care. Some ancient code had been violated. Maybe I felt Jane was being compassionate enough for the two of us. Maybe I’d allowed my anger and grief to harden my heart. I’d taken my lumps, I thought bitterly. She could take hers.

There was one thing Jane and I did agree on. We still wanted a baby. We agreed not to start the process for at least a few months, maybe longer. But we knew if we didn’t get back on the horse soon, we might not have the courage to try again. Then we’d spend the rest of our lives looking back at what might have been had Lily lived. >

I knew she was irreplaceable. I was terrified of being responsible for the life of another child. But I needed some kind of hope in my life. And somewhere, there had to be a baby who needed us.

Then Jane said something I will never forget: “Someday, we’ll look back at this and realize that we had to go through Lily’s death to find the baby we’re supposed to be with.” I loved her for saying that.

***

SOME WEEKS AFTER THE FUNERAL, I heard about the Northern Virginia SIDS Alliance from a woman who had a daughter on Molly’s soccer team and whose sister-in-law was president of the chapter. “You might want to give them a call,” she told me. I did. A few days later, Judy Rainey knocked on the door, introduced herself, and handed me an envelope. Her number was in the envelope, she said. I could call anytime.

Inside was The SIDS Survival Guide, a book filled with the raw stories of parents who had lost babies and struggled through horror, anger, and grief to, finally, acceptance. It helped to know that other people had been through the nightmare and come out the other side. There was advice from grief counselors and chapters on the different ways men, children, and grandparents deal with the death. There was one chapter about being a friend to a SIDS survivor (do use the baby’s name; don’t say it was God’s will; do say “I can’t even begin to imagine your pain”) and even one called “When a Baby Dies at the Child Care Provider’s.”

I wanted to talk to Judy again, to someone who had taken her own tour of the universe of loss. Jane, Judy, and I went out to lunch one day. Judy apologized for bringing along Sarah, her ten-month-old. Some SIDS parents can’t bear to see another’s child. But we were hungry for a baby’s smile.

Over pizza, Judy told us about her son, Joe, who had died in 1996. Like Lily, he had died at his babysitter’s. And like me, Judy had unresolved issues about the sitter. Because she worked across the street, Judy had arrived at the house within five minutes of getting the call that Joe had stopped breathing. But for some reason, the woman hadn’t dialed 911. Judy did that. “I don’t blame her for Joe’s death. But I never understood why she didn’t call for help sooner. And I’ve never really found out why.”

I don’t remember much of our conversation, but I do remember feeling comforted to be in the company of someone who understood my isolation, who understood my fear that I would never get over Lily’s death. I told her how waking each morning was like the movie Groundhog Day, Lily’s death happening all over again. I’d gotten used to suddenly tearing up in public places, and I could now do it over lunch and not even look around to see how people seated nearby were reacting.

Judy was eager to hear everything about Lily: how we’d found her, how strangers would see her smile from 40 yards in a supermarket or at a playground and come over to make her acquaintance. She told us how she and her husband, Terry, had also been terrified to have another child but had been more terrified not to. “My arms just ached for a baby,” she said. She’d been so fearful of SIDS by the time Sarah came along that even at ten months, the child was still sleeping strapped into a car seat placed inside her crib so that she couldn’t turn onto her stomach in the night.

Judy, the unpaid president of the Northern Virginia SIDS Alliance, was on a crusade to save as many babies from SIDS as possible. She told us the Back to Sleep campaign had helped reduce SIDS 40 percent since 1992 but that less than half of all parents regularly put a child down on her back, even if they knew it reduced the risk of death. That a child accustomed to sleeping on her back who was put down prone at daycare was something like 18 times more likely to die of SIDS. That though SIDS is not totally preventable, thousands of children could be saved simply by getting parents, daycare providers, and grandparents to put them down on their backs and remove from cribs the fluffy bedding and soft bumper pads that babies can nose their way into and suffocate.

“All I can tell you is that you will get through this; it will get better,” she said. “But don’t listen to anybody who tells you it’s going to take a year or 18 months. It takes however long it takes.”

***

HIEN’S CASE CAME UP IN COURT IN January 2000, seven months after Lily’s death. She pleaded guilty to all three misdemeanor charges, including exceeding the Arlington County limit on children at a family daycare home and not reporting all the income she had made. Jane attended the proceeding. I did not. I wanted it all to go away. I read in the paper that dozens of parents had showed up to try convincing the judge that Hien should not be sent to jail. One mother said Hien had saved her child’s life by administering CPR during a seizure. Another showed a special chair that Hien and her husband had made for her disabled child. “Sometimes we think [she] did a better job than we did,” said a lawyer who left his daughter in her care.

Jane did not speak in court, but she had agreed to let Hien’s attorney point out privately to the judge that she was in the courtroom and didn’t hold Hien responsible for our child’s death. The judge ruled that there was most likely nothing she could have done to save Lily. He upheld the suspension of her license and gave her probation on the charges she’d pleaded guilty to. After the ruling, Jane said Hien’s mother, a tiny woman, came over, stood before her, and made a deep, wordless bow of thanks.

I realized later that I should have been there–not in support of Hien but to support my wife. I’d let anger blind me to the person who needed me most.

***

JANE, MOLLY, AND I DEVELOPED RITUALS for Lily. We’d light a tiny candle next to the taller ones at the dinner table. We’d light one each Sunday that we went to church. At Christmas we perched an angel of golden foil on the urn that held her ashes.

At Christmas dinner, we counted our blessings: My parents had been spared their lives in the fire; Molly was doing well in school and had a lot of good friends; Jane and I had not fallen apart.

In some ways, the year had been hardest for my father. He’d lost his house and his only grandchild. His younger brother and only sibling, John, had died a few months later. Then Granny had finally let go. She’d lived to be 99. My father was 80. But losing your mother makes you an orphan no matter how old you are.

Dad’s doctor suggested he have no more than one drink a day to cope with low blood pressure and the fainting spells he sometimes had when tired. Never one for half measures, he’d stopped drinking entirely. At Christmas dinner in my parents’ rented apartment, we spiked his eggnog with rum. Halfway through dinner, his face lit up for the first time in months and he started telling stories. My sister and I looked at each other and winked.

Before Christmas, Jane, Molly, and I also went to the NoVa SIDS Alliance memorial service, preceded by a potluck dinner, at a local church. There must have been 200 people crammed into the downstairs activities room for dinner, some still raw and tearful from losses only a couple of months old, others commemorating children who had been gone more than 15 years. It was all right to cry, to laugh, to hold the babies of people you’d never met before but who knew how badly you might need to hold one. At the service upstairs, the name of every child who had died was read aloud as each family came up to receive a glass Christmas-tree ornament with the baby’s name on it. There may have been a dry eye in the house. I don’t know. I couldn’t see well enough.

***

THREE MONTHS AFTER LILY’S DEATH, Jane and I got back in touch with Families for Private Adoption, reactivated the phone, and started running ads. I was surprised at how good the simple act of calling newspapers and dictating copy felt.

At an FPA meeting, I talked to a woman who had adopted through an agency in Oklahoma City run by a lawyer who herself had adopted two children. We called and got the information packet. It was an agency, which meant less control. But we’d learned a lot in the past year about how little control one really has in life. Besides, if you didn’t adopt, you paid only the $150 registration fee.

The deal with the agency was that you made up two booklets about yourself–a brief family story with pictures–and left those on file. When prospective mothers came to the firm’s offices in Oklahoma City or Tulsa, they looked through the books and selected the ones they liked. By November, we had ours on file, complete with pictures of us, Molly, the house, and Snoop. We said we favored an open adoption, in which the child would have the option of contacting the mother when he or she was old enough. We figured Molly–now 13 and a happy, unaffected girl–was our strongest card. We played her up big time.

Once our books were on file, I pestered the attorney, Julie Demastus, with phone calls every two weeks. Had anybody looked at our book? Did they seem interested? At FPA meetings, I kept hearing of couples whose ads in the newspapers had paid off. How had they gotten lucky and not us?

Then one morning, about two months later, the phone rang. It was Julie. “I think we’ve got you a mom,” she said. Pam (not her real name) was 33, seven months pregnant with a girl.

Every adoptive parent hopes for that dream candidate, the honors-club cheerleader who got too friendly with the captain of the football team–who was also the winner of the science fair. The actual women putting up children for adoption tend to come from grittier circumstances. Many grew up in single-parent homes and have low-paying jobs and histories of medical problems or substance abuse. None of this necessarily means there will be anything wrong with the children. We had seen proud parents at FPA meetings showing off impossibly healthy, beautiful babies whose biological mothers sounded like rejects from The Blair Witch Project. Pam was a good candidate: She’d kept all her appointments with the adoption agency, had a steady job, and was healthy. “She just doesn’t think she’s mommy material,” Julie told me. “She picked your book and wants to talk to you-all.”

The three phone conversations we had with Pam went well. Pam was of Italian-Irish ancestry, five-foot-four, 120 pounds. She had a smoker’s voice but said she had all but quit once she found out she was pregnant. She’d been in Alcoholics Anonymous for years and worked in a coffee shop at a hotel. She’d hooked up with a guy briefly but decided he was trouble and dumped him. He had red hair and was of middle height. She didn’t know where he was now and didn’t want to know. She’d never really considered abortion. She was looking for parents who would expose a child to religion but not shove it down her throat. She liked how happy Molly looked. Pam had grown up with four different stepfathers and especially liked that Jane and John had worked things out around Molly so well after the divorce. It sounded like she had limited faith in the institution of marriage.

The baby was due in February–one month away. There was a lot to do before then: letters of reference, an updated home study, fingerprints, copies of our criminal and child-abuse background checks from the State of Virginia. After two attempts at fingerprinting, the authorities gave up on Jane. Her prints were so light that they didn’t show up on the most sensitive electronic equipment. “There are criminals who’d kill for your hands,” the guy operating the machine said.

The baby was scheduled for cesarean section at Mercy Health Center in Oklahoma City on February 25. Pam said it was okay if we wanted to be at the hospital. Jane could even be in the delivery room. We could take the baby immediately and spend the night in the hospital with her. Then we’d need to stay in Oklahoma City for two weeks while the interstate compact was completed, allowing us to take the baby back to Virginia pending final adoption. We made plane reservations, found a hotel with a kitchenette to save on restaurant expenses, and started throwing baby names around. We liked Emma.

I told Jane I was afraid to get too excited. I was afraid it would somehow backfire, that Pam would change her mind. “I know what you mean,” she said. We called Julie Demastus for reassurance. “Look, nothing’s done until it’s done,” she told us. “But I wish all the girls we got in here were as stable as Pam. I think you’ve got yourself a daughter on the way.”

The baby decided she wasn’t on anybody’s schedule but her own. On the morning of February 18, 2000–a year and a day after Lily was born–the phone rang. It was Julie: “You better get on a plane and get down here. Mama’s water just broke. We’ll be at the hospital with her. See you there.” Jane had commitments she couldn’t cancel and couldn’t get away until the next day. It took me four hours and a lot of pleading, but I found a flight out that night at five o’clock.

At 2 AM, a cab dropped me at the hospital. Five minutes later, I was holding a tiny baby girl, a pink bow in her bright-red hair. A photo taken by one of Julie’s staff shows a man suddenly plucked from a sea of grief, smiling and almost crying at the same time.

Pam lay in bed, exhausted, with tubes in her arm. I gave her a kiss on the cheek, and she smiled. “I am so happy to meet you,” I told her. “The baby’s beautiful. We’re gonna take the best care of her we possibly can. Jane’s flying in tomorrow.”

We talked for half an hour. The baby had been born about five o’clock and weighed five pounds, ten ounces. She was almost as big as a loaf of bread, but squirmier, and quite red in the face and not at all pleased to have been kicked out of the womb. Finally a nurse said Pam needed to get some sleep. “I’ll come see you in the morning,” I told her.

I wheeled my new daughter down the maternity ward in a sort of plastic tub on a trolley and into a room with a bed for me. The nurse showed me how to fold and tuck the blanket to bundle her up tight and warm, gave me some bottles of formula, and closed the door. “It’s just you and me now, honey,” I said to the baby. “You and your daddy.”

I curled up on the bed in my clothes and moved the cart so she was just inches away. Every two hours Emma woke, her thin cries signaling hunger. She was so tiny that half an ounce filled her stomach and sent her back to sleep. I had never seen a newborn. Her vulnerability was heartbreaking. I was hooked. With Lily, who had come to us at six weeks of age, the bonds had taken time to form. But Emma was ours from birth, and I was hard-wired to her cries. I had the feeling that the softest sound from her would wake me from any sleep.

She managed the trick that all newborns do, looking ancient and brand-new at the same time. I woke again and again to inspect her in the night. “Emma,” I said. “Do you like that name?”

Later that morning, I took the baby in to see Pam, who was dabbing at tears. “I’m a mess,” she said, smoothing her hair. I told her she looked fine. Just then a nurse came in. “Stitches hurtin’ you, hon?” she asked. Pam nodded. “We’ll fix you up,” said the nurse. A minute later she returned with a shot of Demerol. Pam rolled her eyes. “What I really want is a cigarette,” she whispered to me.

I took the nurse aside, explaining she was about to administer the wrong drug. “Gotcha,” she said. Then she went over to Pam. “Darlin’, I can’t let you smoke in here.” Pam’s face fell. “On the other hand, if you were to light one up when I walk out of here, there’s nothing I could do about it.” She winked and left. I rummaged in Pam’s purse, lit a Marlboro Light for her, and opened the window. After that she calmed down.

I told her about Jane and Molly and the dog, about my writing work and the neighborhood and my parents. She said not to worry about her changing her mind. She was sure. “I knew as soon as you picked her up last night that you’d be a good dad,” she said. She was still crying, though. I didn’t pry about why she wasn’t keeping the baby. I figured she had her reasons.

Jane came later that day, Saturday. The hospital wouldn’t release Emma until she downed an entire ounce of formula at a sitting. That didn’t happen until Sunday, so Jane and I spent a night with her in the hospital room before the three of us moved to the hotel. We went to every Kmart in the Oklahoma City area looking for a certain baby sling that Jane had seen and wanted. We never did find it. We watched TV and took videos of the baby and tried to get her to smile at us. But Emma mostly wanted to sleep. That was fine, too. We were exhausted, elated, and anxious to go home. Her birth had delivered us back to the world of the living. We were already looking forward instead of back. It was a good place to be.

***

SIDS PARENTS ARE UNDERSTANDABLY anxious about subsequent children. Some of us spend thousands on high-tech monitors that go off like car alarms when the child’s heartbeat becomes irregular or the child fails to breathe for a certain number of seconds. Some of us virtually put our lives on hold–not letting the child out of sight–until that first birthday’s deliverance from the danger zone.

What Jane and I learned from SIDS is that calamity tends to blind-side you. “I just figure lightning’s not going to strike twice in the same place,” Jane said not long after we got Emma home. “Otherwise, I’d go crazy with worry.”

We do put Emma down on her back, though she tends to roll over almost immediately onto her stomach. We don’t put blankets, pillows, bumper pads, or anything else in her crib that she could suffocate against. We bundle her in sleepers against cold nights. And we bought a $200 Halo mattress that has tiny holes in it and a fan that continually circulates air.

We’ve hired a wonderful woman named Nancy to come into our house and take care of Emma 30 hours a week. We let my mother babysit often. We’ve become board members of the Northern Virginia SIDS Alliance chapter and have taken a course on peer counseling so that we may one day offer hope to a couple plunged into that parallel universe of loss. That hasn’t happened yet. But enough babies die of SIDS that we will probably need our training.

We still light a tiny candle for Lily at family gatherings. We still have pictures of her on the walls. We want Emma to know about her sister when the time is right. We recently attended the dedication of a small garden created in her honor at my parents’ church in Glen Echo. We have yet to decide what to do with her ashes, which are still in the blue urn on the mantle.

We’ll never get over losing Lily. We don’t want to. Her life is forever part of ours. But we can remember her now without automatically suffering. Emma is learning to crawl, and we are beginning to child-proof the house. She turns her head when we call her name. And when she crawls fearlessly to the edge of our bed when we play with her in the mornings before getting up, sure that nothing in the world can harm her, we tug her gently back to safety. We nuzzle the special spot on her neck and listen as she dissolves into low baby giggles. It is the sweetest sound on earth, a sound that binds us to this child forever, a sound that wraps itself around broken hearts and makes them whole again.

Bill Heavey is a freelance writer in Arlington.