When I was 12, my father and his law partner defended a black man who was charged with first-degree murder in the shooting death of a white Prince George’s County police officer.

The man and his wife lived in Chillum, which in the early 1970s was predominantly white. They asked a neighbor to keep an eye on their house while they were out of town. When they came home late one night, a day earlier than planned, they didn’t alert the neighbor, who saw the couple’s upstairs lights on and called the police.

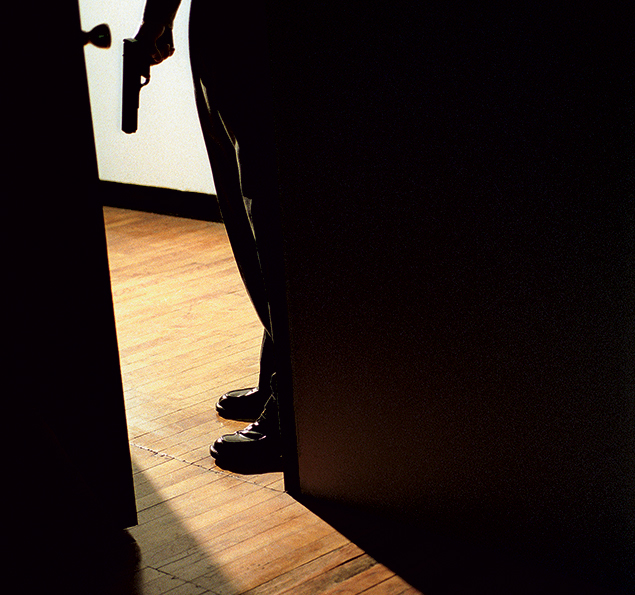

The officers didn’t announce themselves when they approached. Hearing noises, the man grabbed a shotgun. An officer broke a pane of glass in the back door and reached through to turn the knob. Thinking the cop was an intruder, the man shot and killed him.

Upstairs, hearing gunfire, his wife called the police, who at the same time were responding to the call of an officer down. A shootout at the house followed. On 911 tapes, she can be heard screaming that the Klan was attacking their home.

One night before the trial began, I went to the house, by then vacant, with my father and his investigator. At the time, I dreamed of becoming a trial attorney like my father, who in my mind was the perfect mix of Atticus Finch/Clarence Darrow/Daddy. While the two men circled the house, I stood in the kitchen with a police cap on—my dad and the PI wanted to see if they could make out the silhouette of the hat from outside. Alone in the dark room, I was terrified. The house was shredded by bullets. Even the bathtub, which I imagined to be impenetrable, was shattered.

Months later, a jury in LaPlata found the man guilty of second-degree murder. He served less than a year of a ten-year sentence before the conviction was reversed due to a violation of his Miranda rights. Many years after that, he was working as a cabbie when a fare shot and killed him on Central Avenue in Kettering.

As a child of the ’70s, I grew up in a racially polarized time and place. My friends and I were bused from an elementary school in then mostly rural Prince George’s to another close to the DC line, in District Heights. Years later, my mother told me she’d cried when she went to the new school to help sort books for incoming students. While our previous school had had the latest editions, the all-black school had dated, worn supplies.

This fall, my first grandchild will be born, a biracial baby. When I learned of the pregnancy, the usual grandmother concerns included other worries: What would my child know about teaching hers to move safely and confidently through our country?

Even white people like me, deeply concerned about equality, have no idea what it means to live as a black American. We hear what happens to our friends. We can sense the tension, fear, and outrage. We can deplore behaviors and violence. We can hold vigils and tweet our disgust.

Bearing witness matters—but forcing change is far more difficult. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “Human progress is neither automatic nor inevitable.”

What will it take to disarm us of our racism and stereotypes? My black friends who have children teach them lessons white Americans never have to learn. For me, those lessons are no longer abstract. Where will my granddaughter find safety?

I remember how it felt to stand in that dark, bullet-riddled house for five minutes. How must it feel to spend a lifetime there?

Janice Lynch Schuster (jlschuster827@gmail.com) is the author of a poetry collection, “Saturday at the Gym.” Have a story for First Person? Send submissions to Bill O’Sullivan at bosullivan@washingtonian.com.