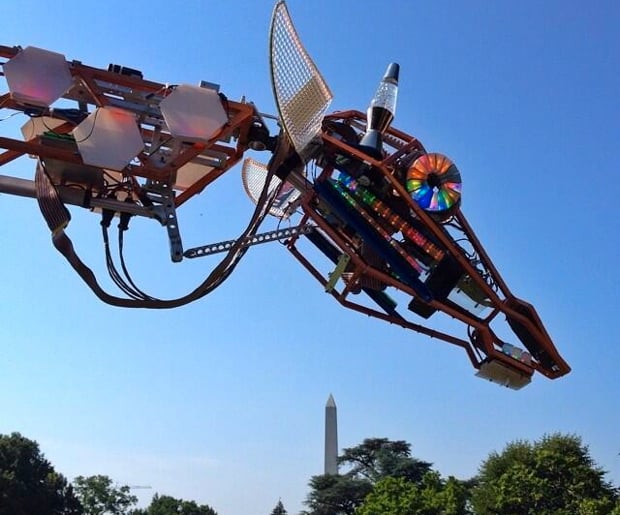

President Obama tickled a 17-foot tall electric giraffe on Wednesday. Silly as that sounds, it was just one of many exhibits at the White House’s “Maker Faire,” a summit celebrating the rise of the “maker movement.”

Maker culture—non-industrial types noodling around to find do-it-yourself fixes to life’s problems—isn’t new, but the past few years have turned hobbyist pursuits into a mainstream phenomenon, and some of their creations—even 2,200-pound giraffes have gone from one-off prototypes to items solving serious problems. Among the other “makers” at todays event were the creators of the Embrace, a portable blanket distributed in developing nations that serves as a low-cost incubator for prematurely born children. Embrace was developed at TechShop, a San Francisco-based chain of workshops that cater to would-be inventors.

TechShop’s newest location opened in April in Arlington, where on Tuesday its employees prepared many of the materials used at today’s White House event, including special badges made by a laser cutting through acrylic sheets.

To make the blue and red badges distributed to today’s Maker Faire participants, Corey Robbins, one of TechShop’s “dream consultants,” transferred the design—an outline of the White House topped by a sprocket—from Adobe Illustrator to printer software that controls one of four laser cutters. Just as people click to print out their homework, Robbins ordered the laser cutter to start slicing.

“It has the potential to inspire young people to get excited about manufacturing and design,” Thomas Kalil, a deputy director in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, told Washingtonian. “It’s democratizing the tools to make anything.”

The White House announced several new policy initiatives, including maker-recruitment programs at the Department of Homeland Security, grants from the Defense Advance Research Projects Agency, and 3-D printed biomedical files at the National Institutes of Health.

“It puts the tools of the Industrial Revolution into the hands of amateurs and pros who get to work on their own projects,” said Mark Hatch, TechShop’s chief executive. “People learn visually, auditorily, kinetically. The best way to get someone into phyiscs: have them build a trebuchet.” (For non-engineers, that’s a siege weapon from the Middle Ages.)

Hatch says TechShop fosters the creation of new products by offering far less expensive fabrication and testing processes than traditional industrial practices. TechShop also boasts among its achievements the prototype for Square, the credit card-reading device developed by Twitter founder Jack Dorsey that attaches to smart phones.

Washington’s recent tech scene is largely software-driven—think of the developers at startup hubs like 1776 in downtown DC or AOL’s Fishbowl Labs in Reston—but there’s a growing appetite for hardware made by people with fresh ideas, but who might not be engineers by training. Besides TechShop, General Electric has a 3-D printer lab on Connecticut Avenue, Northwest, and Navy Yard is about to get Ideaspace, another membership-based tech shop.

Even the DC Public Library is in the maker game; last summer, it opened its Digital Commons at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Library, featuring 3-D printing and do-it-yourself bookbinding.

“It started out with computer hackers, now it’s all different kinds of making,” said Gareth Branwyn, an Arlington-based writer who’s been fidgeting around with robotics since the 1980s. “It’s the same basic impulse, confluence of readily availible tools, and the collaborative power of the internet.”