When my grandmother was 18, she dropped out of college to get married. A career wasn’t a priority for her; matrimony was. This fall I’ll tie the knot at age 29, slightly younger than average for a bride in Washington, where the median age for a woman’s first marriage is 30.

My grandmother, who lived in Connecticut, had her first child when she was 18 and another at 20. With childbearing out of the way and a full-time nanny, she went on to launch a career in politics and at age 28 became a state senator.

As a friend recently mused, “I wish I could have had my kids at 22 when I was nothing in my career. Of course, I wasn’t married or financially secure then.” Now she’s 31 and married, and she recently got a big promotion. “It’s just a really inconvenient time to have kids.”

There are obvious downsides to getting married and having children young–for many women, it short-circuits their careers entirely–and women have made huge gains in the workplace since my grandmother’s time. But the cruel joke of modern womanhood is that my career will probably peak just as it’s time to start a family. This raises more questions: How long should my fiancé, Andrew, and I wait? Should we risk running out my biological clock and needing fertility treatments? If we can afford them, that is.

Speaking of money, how would we afford children if we stay in DC, one of the most expensive cities in the country? Andrew and I have both chosen careers motivated more by our interests than by our paychecks–I’m a journalist, and he works on international climate-change policy at the State Department.

Even without student loans to pay off, we find it hard to save as much as financial planners say people our age should. I’m often reminded of the acronym DINK–dual income, no kids–which should probably be changed to DINA: dual income, need another. Sure, we could move to a less expensive area of Washington or take a job for the salary, but we’re young and not ready to settle. We want to see if we can make life work on our terms.

We’re like lots of others in our generation who–since their parents first turned the television to Sesame Street or sang along to “Free to Be . . . You and Me” in the car–have believed we can achieve anything we set our minds to.

Are we expecting too much?

For the twentysomethings who move here to launch their careers, it’s a time of life when the pressure is intense and the stakes feel high. Many of them are focused solely on work, as they’re unmoored–without a spouse or children–and will remain that way into their early thirties.

They’re trying to make good use of their expensive college degrees, and along the way they’re asking themselves: Is this all I can expect from my diploma? Shouldn’t work be fulfilling? How do I make it in a world where career paths are no longer linear, with so many options and so little job security?

Their concerns may seem trifling at a time when unemployment for people between ages 16 and 24 is in the double digits. But far from feeling lucky simply to have a job, many of today’s highly educated, tech-savvy Gen Yers are asking more from work than previous generations ever did.

They’re in the throes of “emerging adulthood,” a term coined by Clark University psychology professor Jeffrey Arnett to describe a life stage that doesn’t quite have all the contours of traditional adulthood–marked by a marriage license, a mortgage, and a steady job. The concept of this new stage was explored last August in a New York Times Magazine article that asked: “Why are so many people in their twenties taking so long to grow up?”

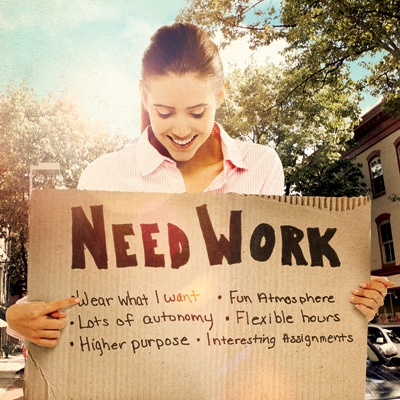

But perhaps it’s not as much that twentysomethings are taking longer to grow up as it is that they’re defining adulthood in new ways, with different goals. Instead of a steady job, they want a meaningful one that serves a larger purpose or fulfills a personal passion. And instead of settling down with a spouse and mortgage, they want more years of freedom to chase career dreams and explore different paths before they have to make tradeoffs.

“Adulthood is a taller order these days,” Brent Donnellan, a professor at Michigan State University who studies the transition to adulthood, tells me. “When we look at surveys at what this generation values, they want a lot.”

As a result, people born between, say, 1980 and 1995 are reconsidering some of the once-sacred aspects of the American workplace. Things such as the 9-to-5 schedule, company loyalty, dues-paying, and hierarchy are being discarded at a fast clip. And we’re becoming evangelicals for the notion that work should be personally satisfying, even in a tough job market.

So what does that mean for someone living through it?

Scott–who asked that his real name not be used so he could speak candidly about his job–was born in 1980, putting him in the first bulging bracket of baby boomers’ children to apply to college. Twenty-five years ago, about half of high-school graduates in the United States went to college. In 2010, 68 percent were enrolled–with thousands more across the globe competing to get into US colleges. In 1998, when Scott applied to college, the top university he ended up at had the lowest acceptance rate in its history–13 percent.

“There’s a self-importance that comes from going to such a competitive school,” says Scott. And why wouldn’t there be? You’ve beaten out tens of thousands of high-school seniors from Mumbai to Minneapolis, and no one is shy about mentioning that fact.

Just listen to the opening-day speeches at any selective college and it’s no wonder kids develop what Scott calls a “messiah complex.” Students are told they’re the lucky few. After hearing that loop for four years, which Scott did, it sticks. They believe they’re the chosen and that a diploma from a college ranked in the top ten by U.S. News is a ticket to an interesting and high-paying job.

That’s what Scott thought–until commencement day.

Scott graduated in 2002 in the midst of the dot-com bust. No one was hiring. His liberal-arts degree was useless. “It felt like a real fall from grace,” Scott tells me. His messiah complex was eradicated by a string of rejection letters.

“It was tough being unemployed, but it was also one of the best experiences because it forced me to think about my identity as something that didn’t just revolve around achieving,” Scott says. “That’s not a real identity.”

Twentysomethings are trying to make good use of their expensive college degrees, and they’re asking, “Is this all I can expect from my diploma?”

Eventually he did find a job as a journalist. He left after three years to get a master’s degree at another brand-name school. After graduation, he was offered a job in the federal government.

Some people wait their whole lives to be tapped for a position like the one Scott landed at age 28. He gets to travel abroad for work and attend interesting events. He can call meetings, assign people under him to write memos or briefs, and get high-level staffers in Congress to return his calls.

Pretty cool, right?

“The government is like the Ivy League–it sounds amazing, but being there often sucks,” Scott says over dinner in Dupont Circle. He’s trying to hold onto the idealism that inspired him and lots of others in his generation to go into public service, but the day-to-day of the job isn’t what he expected.

Scott was shocked that he had to wait a week to get a computer and that the one he was given seemed outdated, with a slow browser. But those are quibbles compared with the larger ethos of the place. “The system is so rigid and slow and often beats down people with fresh ideas,” Scott says.

He isn’t the first government employee to complain about red tape, but instead of just griping he’s looking for ways to take what he’s seen and offer some solutions. What bothers Scott the most? “A lot of government is stuck in an antiquated model. It’s from another generation, not this generation.”

Scott believes that the government is the antipode of the most cutting-edge companies in America–Google, Facebook, Apple. The federal government, with its 2 million civilian* employees, isn’t likely to have a start-up culture, but Scott maintains that even at that size it could do a better job of attracting and retaining young employees who value efficiency, speed, and organizational structures that are flatter.

Scott knows he might sound like an entitled ingrate who thinks he knows it all after working in Washington for a couple of years. But he says he’s driven by a compulsion to point out problems with the hope of fixing them: “I don’t want to see a massive exodus of my generation from government.”

Yet Scott might be the first to leave. Though he could have good career prospects in the federal government, he’s not sure how long he can tolerate the culture.

He knows he has options–the sine qua non of the Gen Y career psychology. He already had one career in journalism. Switching jobs or industries isn’t daunting to him. As Scott sees it, there’s no such thing as company loyalty: “The worst career move would be to stick it out in government for the next 20 years. I feel like I could make a much greater impact outside of the system.”

So between now and his 35th birthday, Scott will probably dabble, not start a family, and take two or three more jobs. This will be exhilarating, but also more stressful than if he were to stay with the federal government for the next three decades.

Scott says that through his twenties he was a textbook case of what Michigan professor Brent Donnellan describes as “overly invested in choices,” afraid he would make the wrong one. But now, as he enters his early thirties, that feeling is dissipating. “You realize that no door is ever fully closed, and if it is closed, it’s not that big of a deal,” Scott says. “You see more of your friends getting married and being in stable jobs, and that isn’t such a bad thing. I’m not looking for the one perfect thing anymore.”

A Pew Research poll asked 18-to-25-year-olds about their top goals, and 51 percent responded with “to be famous.”

When Rebecca Thorman hit a rough patch at age 23, instead of therapy, a soul-searching visit to a healer in Brazil, or a cross-country road trip, she turned to the blogosphere as a way to sort through the coming-of-age issues that kept bubbling up. Thorman, now 28, named her blog Modite.com, a combination of “modern” and “urbanite.” Her posts had headlines such as CAREERS ARE LIKE RELATIONSHIPS, SO ASK YOUR MOM FOR ADVICE and GENERATION Y BREEDS A NEW KIND OF WOMAN.

Thorman suffered the post-college blues. She worked in an entry-level job, was in a so-so relationship, and wondered if this was all there was to life. Her existence, she says, felt inconsequential: “You graduate from college and you want to matter and be a part of something bigger.”

Then she launched her blog, and all of a sudden she was engaging hundreds of people from around the world in a discussion. The Internet gave her a place for connection and community much like neighborhood bars and churches did for previous generations.

Thorman is part of the 25 percent of twentysomethings today who say they have no religious affiliation. “What people in the past might have gotten from church, I get from the Internet and Facebook,” she says. “That is our religion.”

But blogging isn’t just about community and connectivity. It’s fundamentally about the individual. “I like blogging because I feel like a mini-celebrity,” Thorman says.

She’s not the only one to express that sentiment. “Attention is my drug,” Julia Allison told a New York Times writer. Allison is a Georgetown grad who became an Internet celebrity in her twenties and whose photo landed on the cover of Wired magazine with the headline GET INTERNET FAMOUS! EVEN IF YOU’RE NOBODY–JULIA ALLISON AND THE SECRETS OF SELF-PROMOTION. A Pew Research poll asked 18-to-25-year-olds about their generation’s top goals, and 51 percent responded with “to be famous.”

But Thorman doesn’t want fame in the Paris Hilton way–famous for being famous. She wants to be recognized, on the Internet, for her insights and ideas.

In 2010, Forbes named Modite.com one of the top 100 Web sites for women, saying, “Entrepreneur Rebecca Thorman writes with fury on the state of the Gen-Y generation, women and work.” She has been quoted in the Wall Street Journal and Los Angeles Times without ever schmoozing with media types at cocktail parties or having parents with connections. At another time, to get that kind of recognition she probably would have had to move to New York, take an entry-level job at a women’s magazine, and try–perhaps for years and with no guarantees–to get noticed.

The blog was the best career move she’s ever made, Thorman says. She used Modite.com as a résumé, showing that she could build a community and that she had expertise in social media, communications, and PR. It was enough to convince the founder of Alice.com, an e-commerce company, to hire her. At 25, Thorman had a great title, a lot of responsibility doing something she believed in (“It’s not just a job–it’s an opportunity ‘to disrupt a market,’ encouraging shoppers to buy online instead of at Walmart and Target”), and one of those cool jobs at a start-up.

But Thorman says the job–which involved overseeing a PR team in San Francisco, updating the company’s blogs, and monitoring its social-media accounts–got boring. So she quietly launched a new blog, Kontrary.com, with the goal of becoming part of the online intelligentsia–the kind of blogger whose musings get linked to on the Atlantic Wire and Slate.

“What people in the past might have gotten from church, I get from the Internet and Facebook. That is our religion.”

Kontrary.com was Thorman’s opportunity to flex her intellectual muscle. She set out to write about gender theory, intellectual property, and how social media shape our lives. She decided to charge users $7 a month and then raised the amount to $12–almost as much as a subscription to the Wall Street Journal. By June of 2011, she had 75 paid subscribers.

Not only did Thorman charge for content at a time when only the leading business publications did, but she branded herself as one of the cognoscenti without having academic credentials. She adopted the tone that has come to dominate the blogosphere: authoritative, declarative, and brimming with confidence.

“The word ‘bold’ has been the most popular word people use to describe the Kontrary launch,” Thorman says. “I think that’s fascinating. Is Generation Y so self-effacing that when someone values their own work it’s considered bold? One person came out and said it was arrogant.”

Through the eyes of another generation–and probably some in her own–Thorman may look more than a little self-important. But she says she’s just experimenting. She knows that job security doesn’t exist anymore–her company could go belly up like so many other dot-coms–so she has to find ways to safeguard against that possibility. In that way, she’s just adapting to the realities of the workplace, circa 2011–that everyone should have a plan B and a side gig.

Like most twentysomethings, Rebecca Thorman lives in the spotlight of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, and Flickr, and as the accomplishments of her peers become more public than ever, there’s a heightened sense of competition.

In Washington, she’s surrounded by overachievers–some of whom, such as her boyfriend, Ryan Healy, have gotten funding for their companies practically straight out of college–and she doesn’t want to be left behind just working at some “normal” job.

Call it the Mark Zuckerberg Effect. At 26, the Facebook cofounder was Time’s Person of the Year. And all over the country there are knockoffs of Zuckerberg–young people upping the ante for their peers. AOL ran a story called meet the new young millionaires, about people under age 33. Yahoo ran a feature called how to be a millionaire by 35, filled with real-world examples.

A commenter on a Gen Y blog described the landscape: “I feel like, at 23, I should be starting my own design studio, have tons of clients and work experience, and be at my peak.”

No doubt this mentality is the midwife of Thorman’s anxiety and self-criticism. Looking around at other people her age–both in real life and on social media–she says, “I feel like everyone has figured it out except for me.”

When Levi Strauss, the jeans company, surveyed “millennial” women in five countries–the US, the UK, Japan, France, and Brazil–83 percent said they believed they were expected to be more successful than women in previous generations. As Courtney E. Martin put it in her book Perfect Girls, Starving Daughters, “We are the daughters of feminists who said ‘You can be anything’ and we heard ‘You have to be everything.’ “

Our older siblings, parents, and grandparents look at Gen Y and shake their heads about our high hopes.

Now we ostensibly have the time to be everything. With the loosening of the marriage timetable, giving young women ten years or more to focus only on their careers, Thorman wants to make the most of this decade and get a serious jump-start on being successful before she settles down.

It would be reasonable to assume that the recession would have tempered the expectations of most twentysomethings about work–making them happy just to have a job. That’s not necessarily the case.

“Many decided to move home and wait out the bad economy instead of just taking any job,” says Lindsey Pollak, global spokesperson for LinkedIn and author of Getting From College to Career: 90 Things to Do Before You Join the Real World.

Isn’t that kind of nuts?

Perhaps. Older siblings, parents, and grandparents look at Gen Y and shake their heads about our high hopes, scolding us for not taking whatever job we’re offered–or for leaving seemingly good ones to chase the next opportunity. They may be right, or they may not understand what it’s like to be young when there are so many options, when moving home isn’t a point of humiliation, and–at least until a certain age–when there’s no rush to commit to anything.

Barry Schwartz, a professor of social theory at Swarthmore who studies choice, found that twentysomethings are more likely to want to make the “best” rather than the “good enough” decision. They want to try five types of cookies, careers, or relationships to find the optimal one. This kind of thinking can lead to disappointment and bad decisions but also to the cure for cancer, the next great American novel, or Google, which was founded by two twentysomethings.

Even if lamenting about “kids these days” is an American pastime that dates back centuries, there might be an added edge today: jealousy.

“Who doesn’t want to love their work? Who doesn’t want to choose their career path? I want that stuff,” says Lindsey Pollak.

However, it’s not everyone’s to have–ballooning student debt means there’s a schism in this generation between those who are drowning in debt and those who aren’t. And young people lucky enough to have parents willing and able to provide a financial safety net have a huge advantage–it’s a lot easier to take risks if you know Mom and Dad will never let you go broke.

In June, Rebecca Thorman shut down Kontrary. “I wasn’t getting the kind of exposure I was hoping for,” she tells me. She’s now trying to reengineer her position at Alice.com to be director of the company’s media arm. Either way, she isn’t worried.

After spending the last few years building expertise in grassroots marketing, starting blogs, and running social-media campaigns, Thorman believes she has skills that are sought after. She has tapped into that Gen Y gold mine: figuring out how to get people to pay attention to you online. “I’d have a job tomorrow if I left Alice.com,” she says.

Thorman wants a career that challenges her and aligns with her values and interests–something she’d hoped Kontrary.com would be. Now she’ll either figure something else out or she’ll end up like the legions of young people who are disappointed with their work. A 2010 study by the Conference Board found that job satisfaction for workers under age 25 is at a record low, with fewer than 40 percent reporting that they’re satisfied with their current jobs–the lowest percentage among all age groups surveyed.

Those figures come as no surprise to Barry Schwartz. “Expectations in this generation have gone through the roof,” he says. “The secret to happiness is modest expectations.”

“Recently, I’ve thought that I’m just an inherently lazy person.”

“Recently, I’ve thought that I’m just an inherently lazy person,” says Lauren (not her real name), a 29-year-old attorney. Lauren isn’t lazy–she’s an Ivy League graduate who worked for a high-ranking Democratic senator on health policy, went to a top law school, and is now a first-year associate at a well-known DC firm.

“There is a drive to the more senior people in my law firm that I just don’t have,” Lauren tells me over drinks at a trendy bar in downtown DC. “Sometimes,” she goes on, her voice lowering to let me know she’s about to make a confession, “I turn down work.”

In the universe of first-year associates, that’s career suicide. In most firms, if a superior says, “Jump,” first-years ask, “How high?” Lauren says she knows this: “But sometimes I just want to have a life.”

When I ask if she has ever missed a deadline, botched an assignment because she got distracted g-chatting, or overslept because she’d been out late the night before, her answer is “God, no.”

Lauren’s worst transgression occurred when a partner asked her to read 500 pages from the Federal Register over a weekend and she said she’d need a week to get through it.

Lauren says she’s willing to work hard, but she isn’t going to kill herself at a job where she’s not vying for the gold medal: partnership. Like other young lawyers, she asks, “Why sacrifice my life for something I don’t even want that much?”

Unlike lawyers in previous generations, Lauren doesn’t see just one career path–she sees options that could land her anywhere from a think tank to a start-up: “No one goes to law school anymore to become a partner at a firm.”

In some ways, Lauren’s work does fulfill her. “It’s intellectually satisfying,” she says. “I feel challenged on a daily basis. I work with smart people.” Shouldn’t that be enough?

For one thing, her job–like those at many large law firms–is isolated. She sits at a computer and considers it a “social day” if she has a single face-to-face conversation that lasts longer than ten minutes and isn’t part of her lunch break. “I like being around people, and if I didn’t get that outside of my job, I’d be miserable,” she says. In the long term, Lauren doesn’t want to search outside work for social interaction: “I want to get it at work.”

Tammy Erickson, a Boston-based inter-generational-workplace expert and author of Plugged In: The Generation Y Guide to Thriving at Work, believes that young lawyers such as Lauren are ubiquitous. “Who wants to spend ten years doing crappy, boring work just for this carrot that she may or may not get?” Erickson says. “This generation doesn’t want to work for 60 years and then enjoy life. They aren’t into deferring gratification.”

That matches Erickson’s other observation: “This is the most fulfillment-driven generation in the workplace.”

But what does that mean? Doesn’t everyone want a fulfilling and satisfying job? While many say it’s something they value when asked about it in the abstract, it’s the twentysomethings such as Lauren who are singularly focused on finding a job they like. And today there are more single, childless twentysomethings than ever–meaning there are more young people than ever who are unencumbered by kids and a mortgage, which often require people to rethink their priorities and take a job for the money.

Doesn’t Lauren feel lucky to have a job when, just three years ago in 2008, the number of laid-off lawyers hit a ten-year high?

Yes, but she isn’t motivated enough by money to stick with her job, even though she has law-school loans to pay off. Her plan is to stay at the firm two years, pay off her debt, and then take a much lower-paying job working for the government on food policy. With no boyfriend and with kids a long way off, she can afford to make decisions that often translate to employers and parents as foolhardy, walking away from a seemingly “good job.”

What Lauren is chasing, and not finding as a first-year associate, is the satisfaction that comes from what retired Supreme Court justice Sandra Day O’Connor said was the key to a happy life: “Work worth doing,” as she told Gretchen Rubin, one of her former law clerks and the author of The Happiness Project.

Lauren is a prime example of a phenomenon Barbara and Shannon Kelley, authors of Undecided: How to Ditch the Endless Quest for Perfect and Find the Career–and Life–That’s Right for You, call “the spiritualization of the career world.” Touchy-feely career guides call it finding your passion, and the more down-to-earth call it finding what makes you tick. I’m pretty sure our grandparents called it work.

Lauren wrestles with the balance between wanting a lot from her job and the reality that she has bills and debt. Her parents and grandparents didn’t have the kinds of expectations for work that she has: “My mom never even thought about a career. She was supposed to marry her high-school boyfriend and become a housewife.”

Lauren wants to do something meaningful, putting her in step with what countless surveys find: Twentysomethings want careers that have an impact beyond their bank account.

“I feel the need to contribute to society,” she says. “It comes from the fact that I feel so incredibly fortunate that I was able to go to college, live in a wonderful city, and go to an incredible law school. I definitely feel like I have more privilege than my parents.

“One thing I wonder is if you can ever love a job. That would be so amazing if you found something you felt passionately about and every morning you woke up and were excited to go to work.”

“Do you know people like that?” I ask.

“Yeah,” she says. “They are entrepreneurs.”

The original version of this story stated the federal government employs 2 million people. The story was corrected to read the government employs 2 million civilian employees.

Hannah Seligson is working on a book about twentysomethings called Mission: Adulthood, which will be published by St. Martin’s Press in September 2012. More information about her work is at her Web site.

This article appears in the November 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.