Irvin and Israel “Izzy” Feld, Maryland-born sons of Jewish immigrants, were the region’s reigning kings of gospel-music promotion when Sister Rosetta Tharpe met them around 1949.

Allen Bloom, who worked for the Felds, remembers Rosetta’s walking into Super Cut Rate—their drugstore turned record store in DC’s Seventh Street shopping area—to propose a business deal. Others heard that the Felds sought out Rosetta because her music sold so well among their customers.

Either way, it was a match made in heaven: Rosetta, the gospel musician always looking to reinvent herself, and the brothers with good ears and marketing instincts who had created a music empire before Irvin Feld’s 30th birthday.

Rosetta, an Arkansas-born vocalist and guitarist from the Pentecostal tradition, was one of the most remarkable musicians of the 20th century. In the 1930s, she began a career as gospel’s first national star and the most celebrated guitarist of its golden age—so called because it saw the emergence of the genre’s defining artists.

Rosetta’s dazzling guitar playing, which featured a finger-picking style unusual at the time, influenced Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, Etta James, Little Richard, Bonnie Raitt, and many others. Her 1945 crossover hit, “Strange Things Happening Every Day,” a jab at religious hypocrisy that became a favorite of Elvis Presley’s, may well be the first rock-and-roll song.

Initially, the Felds promoted Rosetta—who then lived in Richmond—in places like Turner’s Arena, a 2,000-seat auditorium at 14th and V streets, Northwest, primarily known for hosting boxing and wrestling matches. But in 1950, the Felds ratcheted up their ambition.

Rosetta was no stranger to big shows, especially when she toured with her best friend and musical partner, Marie Knight. The two had played to a crowd of 17,000 at Atlanta’s Ponce de Leon Park. If it could be done in Atlanta, it surely could be done in the District, with its many Southern migrants.

The Felds set their sights on promoting Rosetta at Griffith Stadium, home to the American League Washington Senators and Negro League Washington Grays. The stadium stood in the heart of Shaw, black DC’s most vibrant neighborhood.

Up the hill to the north was Howard University, the nation’s preeminent black institution of higher education. To the south stood the Gospel Spreading Church of God, home base of Elder Solomon Lightfoot Michaux, a charismatic preacher whose CBS radio shows and socially conscious ministry had made him a celebrity during the Depression. South of the church was a residential area, home to blue-collar workers as well as the relatively privileged, including Duke Ellington, who had sold peanuts at Griffith Stadium.

Although Clark Griffith, the stadium’s owner, was infamous for his resistance to integrating baseball, Griffith Stadium “was sort of like outdoor theater for the black community,” historian Henry Whitehead recalled. In segregated DC, where black people could see the Capitol reflected in the windows of establishments they were forbidden to enter, it was an important civic space.

In using Griffith Stadium for a gospel concert, the Felds followed precedents established by Elder Michaux. Like Rosetta, Michaux was famous for mixing piety with pageantry, often to the detriment of his reputation for religious sincerity.

In 1938, he began renting the ballpark for “spectaculars,” outdoor events that featured singing, preaching, and mass baptisms. Michaux drew crowds of 20,000, mostly African-American, although his audiences included white notables such as First Lady Mamie Eisenhower. On one day in 1949, more people came out for Elder Michaux’s annual spectacular than for the Senators/Tigers double-header played at the stadium earlier in the day.

In planning their 1950 concert for Rosetta, the Felds took their cue from such theatrical and profitable affairs. Like Michaux, who used fireworks to dramatize Bible scenes, they hired a fireworks company to produce a state-of-the-art display. The Felds also hired the Golden Gate Quartet and Elder Smallwood E. Williams, pastor of Bible Way Church, who had won a 1948 Afro-American newspaper contest as most popular preacher in the District.

Because Rosetta and Marie had recently returned to the recording studio after splitting up—their recording of “When I Take My Vacation in Heaven” was going up the spirituals chart—the Felds billed the show as a reunion concert: SISTER ROSETTA THARPE and madam marie knight, together again for this performance only.

The reunion concert did well, but it didn’t succeed on the order the Felds had hoped for. Nevertheless, as soon as the July 1950 appearance was over, they started preparing for a second show.

Unlike her mother—known as Mother Bell—Rosetta wasn’t an evangelist, so she couldn’t conduct a revival in the stadium à la Michaux and other celebrity preachers. Then it hit Irvin: They could combine a concert and a wedding, with Rosetta the star of both. Didn’t everyone love a wedding?

Irvin didn’t beat around the bush, Izzy’s wife, Shirley, recalls: “My brother-in-law said, ‘Rosetta, find a husband. We’ll promote the wedding.’ ”

Rosetta—35 years old and twice divorced—didn’t need much convincing. That night, she signed a contract promising to produce a groom by the new year. By the following spring, Rosetta had found her future husband—Russell Morrison, a handsome man two years her junior.

Russell couldn’t sing or play an instrument, but he was drawn to the glamour of the jazz life. As a young man, he had done what he could to make himself useful to musicians. He took odd jobs and eventually landed a position as valet with the Ink Spots in 1941.

Janis Joplin, the white blues singer, is usually credited as the first female “stadium rocker.” Yet the phenomenal success of Rosetta’s 1951 wedding concert at Griffith Stadium demonstrates how incomplete popular memory can be, especially when it comes to gospel, which has never enjoyed the broad appeal of jazz or rhythm and blues.

Rosetta wasn’t a rock performer by any conventional definition. Her music never targeted a youth audience, and despite excursions into secular music, she saw herself primarily as a religious performer. Yet on July 3, 1951, a balmy summer evening when Washington’s trolleys and buses sat idle because of a strike, she outsold the hometown Senators.

Decca, which made a recording of the wedding concert, put the crowd number at 22,000, speculating that 30,000 or more would have come had traffic not been snarled. The Afro-American, which featured the story on its front page, said 15,000. Ebony guessed 20,000.

Whereas the Felds usually publicized concerts through signs or radio, this time they had taken out ads in newspapers:

wedding bells ring out for . . .

SISTER ROSETTA THARPE

witness the most elaborate wedding

ever staged! everybody is welcome!

plus world’s greatest spiritual concert!

Advance admission ran from 90 cents for seats in the nosebleed section to $2.50 for the first-base dugout. Not even Rosetta’s half-sister Emily, who came up from Arkansas for the event, got a free ticket.

Reverend Samuel Kelsey, a popular pastor in the Church of God in Christ—a Pentecostal denomination known as COGIC—and a recording artist, had been tapped to perform the ceremonial honors. Rosetta knew him well, having visited his church, Temple COGIC, when she was in Washington.

The Felds assigned all of the musicians supporting roles in the wedding. Marie beamed in a colorful gown as Rosetta’s maid of honor, and the backup-singing Rosettes sparkled as her rainbow of bridesmaids, each in a different color.

The dapper bandleader Lucky Millinder, whose career had come upon hard times in the early 1950s, put in a guest appearance as Russell’s best man. A boy who lived with his mother in a small apartment above the Felds’ Super Cut Rate store was ring bearer.

Together with Mother Bell and the others, they formed a procession that began at the third-base dugout and led to a stage at second base. Last out—marching regally to the “Bridal Chorus” from Wagner’s opera Lohengrin—was Rosetta.

From the upper deck, women squinted to get a look at her outfit. Rosetta had spent about $1,500 on it, the average price of a new car in 1951.

In addition to $800 on the gown—white lace nylon with a five-foot train, scoop neck, and sheer lace sleeves that attached by a loop to the third finger of each hand—she had spent $350 on a sequin-trimmed veil that hung from a rhinestone-and-pearl-encrusted tiara and $400 on a bouquet of white orchids and ostrich feathers. Satin heels peeked out from under her hem.

The dress had been driven up to DC from Thalhimer’s, the Richmond department store where Rosetta had bought it. “Nobody rode with the gown but the person driving the car and the lady that was going to arrange it,” Lottie Henry, one of the Rosettes, recalls.

What Shirley Feld remembers most vividly is the race of the woman sent up from Richmond to fit Rosetta: She was white.

“Thalhimer’s was the leading department store, and they didn’t even want to see a black person walk in,” Shirley says. “But because it was Rosetta Tharpe and she bought this expensive wedding gown, they sent the bridal consultant with the gown to get her in it. And that wasn’t easy—it had like a thousand little buttons down the back. It was a big thing for a white to have to button a black into something.”

It took 20 minutes for the wedding procession to assemble at the altar, decorated with a white lattice draped in white gladioli and American flags. Reading from the DC marriage ceremony, Reverend Kelsey asked the crowd of 20,000 whether anyone knew why the couple couldn’t be married: “Speak now,” he said. “Don’t talk tomorrow!”

By the time he got to the vows, Kelsey was in his element. He referred to the possibility of divorce and teased the groom about his authority over his bride. With a winking tone, he delivered the admonishment to both parties to “forsake all others” and drew giggles from women in the stands as he instructed Rosetta to “obey” and “serve” her husband.

References to Russell’s semiornamental role in the affair received the biggest reaction. The crowd broke into laughter when Kelsey asked mock-innocently, “Do you have a ring, Russell?”

The concert followed the vows. The Sunset Harmonizers did “Gospel Train,” the Harmonizing Four “Thank You Jesus for My Journey.” Rosetta, still in her wedding dress, sang and played electric guitar.

Accompanied by the Rosettes, she did “So High,” a familiar song at Reverend Kelsey’s church, as well as “God Don’t Like It,” her song about the sinfulness of alcohol, which mixes two parts Louis Jordan cheekiness with one part Wings Over Jordan holiness. She and Marie also performed several of their recently recorded songs, including “Revival Telephone,” which picks up on the longstanding Pentecostal metaphor of a telephone to heaven.

The concert concluded with fireworks. In addition to the “lifelike reproduction” of Rosetta strumming her guitar, there were a display of Cupid’s hearts pierced with arrows and simulations of Niagara Falls. By the time the last sparklers fizzled, it was almost midnight.

Like Elder Michaux’s spectaculars, the wedding concert thumbed its nose at middle-class conventions of piety. From Rosetta’s perspective, the event was a triumph, melding her entrepreneurial, spiritual, and artistic ambitions. She told reporters: “I am happier than I’ve ever been in my life!”

The Griffith Stadium show is the best-remembered concert of Rosetta’s career. She made memorable recordings, but the essence of her art lay in her ability to communicate with an audience.

The crowd that turned out for her wedding concert was the proof Rosetta needed at a crucial time in her career—when gospel singer Mahalia Jackson’s fame was overtaking hers—that she could still rely on her gift.

The event also allowed her to combine blushing-bride modesty with uninhibited musical authority. Rosetta, like other female musicians, rarely got to inhabit those simultaneously. The concert created a space where the good and the bad woman, the domestic goddess and the guitar goddess, could coexist.

Rosetta’s wedding and concert embodied feelings of community and hope that took her audience outside of their everyday lives. As a testament to the closeness they felt to her, these fans came to Griffith Stadium dressed for church. Some came with dates, others with children who were expected to sit still and behave. Many brought wedding presents: silverware, lamps, rugs, jewelry, even television sets.

The wedding concert was the Felds’ biggest success to that date. Allen Bloom, only 16 at the time, recalls taking home $7,500 in cash. Much of his earnings came from the sale of souvenirs—from program books to novelty items like lucky key chains, “holy” handkerchiefs, and midget Bibles, which he had rubber-banded together with miniature magnifying glasses.

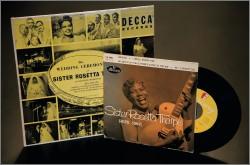

In addition to various singles—both solo and with Marie—Rosetta issued two Decca albums in 1951: Blessed Assurance and The Wedding Ceremony of Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Russell Morrison.

Blessed Assurance compiled contemporary as well as traditional material and featured Rosetta singing—but not playing—songs such as “What a Friend We Have in Jesus” and “Amazing Grace.” It had the imprimatur of folklorist Alan Lomax, who contributed album notes that said, “Sister Rosetta Tharpe is basically a folk-artist, with a hold on a great folk audience.”

The Wedding Ceremony was a novelty item, a recording of the marriage rites in their joyful irreverence, complemented on side B by selections from the concert that followed.

Blessed Assurance was an earnest musical endeavor, while the wedding had been a stunt to keep Rosetta in the headlines. In this respect, it succeeded—but at a price. Even as the wedding had celebrated her standing as a gospel attraction, it compromised some people’s sense of her as an artist.

Ebony detailed the extravagance of the affair while holding its nose. If 20,000 people came out for the wedding, the article implied, another 20,000 stayed home from embarrassment.

In England, where Rosetta had acquired an audience among jazz aficionados, Melody Maker complained that the wedding concert sounded “more like a circus performance than an act of the church.”

Exhausted and ready to return to normal life, the Rosettes retired after a “honeymoon tour” that followed the ceremony. Rosetta returned to Richmond but didn’t stay long. Now married for a third and final time, she was headed to Nashville and points beyond.

Epilogue

Irvin Feld predicted that Rosetta’s Griffith Stadium triumph would be her last. He was partly right. By the mid 1950s, as Mahalia Jackson’s career flourished, Rosetta’s faltered. Decca’s feeble attempts to turn her into a rhythm-and-blues act failed to draw new fans, and her gospel audiences dwindled. Mismanaged finances led to the loss of her beloved Richmond home.

A 1957 British tour opened the door to new audiences and star treatment in Europe, where a postwar generation wanted to hear “authentic” African-American sounds. Abroad, Rosetta happily adopted the mantle of rock-’n’-roller. The kids behind the British invasion listened and learned.

Rosetta Tharpe died in Philadelphia in 1973, amid preparations to record a new album of gospel favorites.

Gayle Wald is an English professor at George Washington University and author of Crossing the Line: Racial Passing in Twentieth-Century U.S. Literature and Culture. She wrote the liner notes for a 2003 Rosetta Tharpe tribute album, Shout, Sister, Shout! This article is excerpted from the book Shout, Sister, Shout!: The Untold Story of Rock-and-Roll Trailblazer Sister Rosetta Tharpe, copyright © 2007 by Gayle F. Wald. Reprinted by permission of Beacon Press.