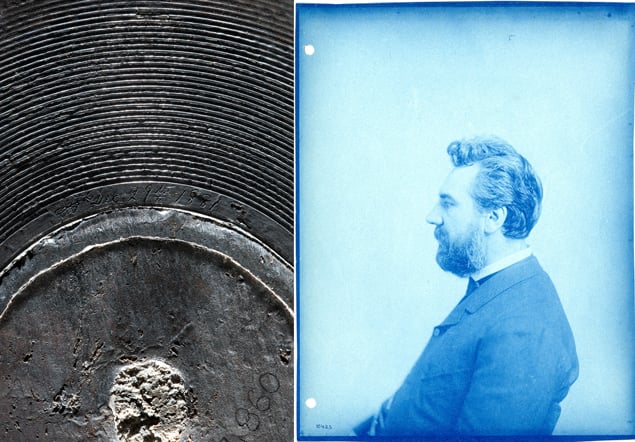

It’s common knowledge that Alexander Graham Bell created the technology for the device now glued to most people’s hands (or ear) 24-7. Perhaps not as well known is that he was instrumental in improving Thomas Edison’s design for the phonograph, which allowed sounds to be recorded and played back for the first time—and that the breakthrough happened at Bell’s Volta Laboratory at 1537 35th Street in Georgetown, now a National Historic Landmark. “ ‘Hear My Voice’: Alexander Graham Bell and the Origins of Recorded Sound”—opening January 26 at the National Museum of American History—brings this legacy to light through artifacts from the inventor’s experiments in the late 19th century, including some of the earliest voice recordings in history.

The exhibit comprises two tales of innovation and invention, says curator Carlene Stephens. The first involves developments in recorded sound in the 1870s and ’80s; the other is decidedly more modern. “In the 2000s, a technique was developed at California’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory for recovering sound without touching some of the really early, damaged, otherwise silent records,” Stephens says. This method allowed scientists to retrieve sounds from a handful of 1880s recordings, among them the only confirmed record of Bell’s voice and one featuring his father, Alexander Melville Bell.

Visitors can hear Bell speak—“It makes the hair on the back of my neck stand up to hear the sound across the centuries,” says Stephens—as well as learn about the new technology that makes the experience possible. Other items in the exhibit include Bell’s handwritten transcript of his recording and a hand-drawn map of DC’s Scott Circle, a reproduction of the original housed in the Library of Congress. Stephens hopes visitors’ eyes will be opened not just to Bell’s work in Washington but also to the idea that the ability to play back sounds, now so commonplace, is a fairly recent development. “It’s impossible for us to think of a world where there is no recorded sound and how incredible that was,” she says. “If people come to reflect on that path from then to now, I think we will have done something good.”

Through October 25; americanhistory.si.edu.

This article appears in the January 2015 issue of Washingtonian.