In 1989, with Nancy Reagan‘s memoir My Turn about to be published, Washingtonian Editor Jack Limpert wrote former White House Chief of Staff Donald Regan, who Nancy Reagan had helped push out of office, and asked him whether he’d be interested in reviewing it. As Limpert recounts on his blog, he told Regan, “Please note that by ‘review’ I don’t mean a literary analysis; rather, we’d like to give you the space to react to Mrs. Reagan’s memoirs in whatever fashion you think would offer our readers the most insight.” This was what Regan wrote, and what Washingtonian published in December 1989.

The best-kept secret of the Reagan administration, zealously guarded by all the president’s men with the tacit collaboration of most of the media, was not the existence and pervasive influence of the first lady’s astrologer but the haunting suspicion that not too many people loved and admired Nancy Davis Reagan … and vice versa. Now Mrs. Reagan has published book that tells the whole world why.

In this extraordinarily revealing gloss on one of the most photographed and least examined of public lives—this amazing autobiography withstanding—Mrs. Reagan and her collaborator, William Novak, seem to have striven for Hollywood studio biography. Instead, they have produced classic of inadvertent confession. Very sadly, and most of all, this book gives aid and comfort to those who still believe that Ronald Reagan never should have been elected president in the first place. It will surely trouble and disappoint many who remember him one of the best.

“There’s wall around him,” Mrs. Reagan explains. “He lets me come closer than anyone else, but there are times even feel that barrier.” It seems to this reviewer, however, that rather than break down, she joined him behind that barrier in world of their own making. She seems incapable of understanding how her words and deeds might seem selfish, hypocritical, and, indeed, even frightening to those the outside.

Few would suggest that she hasn’t succeeded in accomplishing the ambition she articulated as a contract player at MGM—“to have a successful marriage.” She has worked so hard to achieve an ideal union with her husband, she says, that her stepchildren and even her own children sometimes felt excluded. She makes no apology for that, or for the essentially isolated life that the two have chosen to live together— and for compelling reason.

After being told by Librarian of Congress Emeritus Daniel Boorstin at dinner party: “We have never had presidential couple like the two of you, and that alone an important historical fact,” the president replied, “You know, if Nancy Davis hadn’t come along when she did, would have lost my soul.” In the context of his wife’s story, an understanding of the president’s remark clear.

The leitmotif of this book is the indispensability of Nancy Reagan to the presidency, indeed to the personality, of Ronald Reagan.

Mrs. Reagan reminds that “…so many people underestimat[ed] Ronnie for long,” and “people find hard believe that such nice man could be effective, and that he could also be tough when he had to be.” But never fear. As she points out more than once, Nancy has the qualities that her husband lacks.

While he tends to believe the best of people and has trouble firing incompetent aides or those who have caused, or might cause, embarrassment to the president, she has “strong instincts about people, and I’m good judge of character.”

He does not, however, often seem to heed her advice in time. When Nancy was trying to get the president to fire this reviewer chief of staff, Reagan was reluctant to do she asked. In frustration, she cried, “I was right about Stockman. I was right about Bill Clark. Why won’t you listen to me about Don Regan?”

By Mrs. Reagan’s own account, most of her suggestions were about personnel. Judging from a rogues’ gallery of presidential aides and others whom she runs through the wringer of William Novak’s word processor, the Reagans must never have felt the lack of lively back and forth regarding her “suggestions.”

Time and again, this reader was struck by the lack gratitude expressed by the former first lady to those people who helped her husband get to the White House and bring about the Reagan Revolution. they were as bad as all that, one wonders how they helped Ronald Reagan to change the nation’s moral its social goals, its foreign and domestic policies, and perception of itself in more profound ways than any but the greatest of his predecessors.

***

Although I am clearly the front-runner for the office of arch-villain, almost nobody besides George Shultz meets the author’s rigorous, not to say mystifying, standards of loyalty, performance, and discretion. She savages some of the president’s strongest advisers.

Jim Baker is dismissed with these words: “Although Jim did a lot for Ronnie, I always felt that his main interest was Jim Baker.” Besides, “He also cultivated the press assiduously—perhaps too much, because he leaked constantly.” That ought to give Jim a chortle, coming from a first lady who may sometimes have arranged to communicate with her husband through stories planted the Los Angeles Times and who says that she counted among her best friends in Washington Kay Graham and Meg Greenfleld of the Washington Post and columnist George Will.

What of Ed Meese, the dogged California loyalist who devoted the heart of his career to Reagan? Sorry! Ed was just too conservative. He gets belittled by such terms as “jump-off-the-cliff-with-the-flag-flying conservative.” If that isn’t enough, he also “made a series of [unspecified] mistakes which embarrassed the presidency,” and he was disorganized and “weakened both the Justice Department and the presidency.”

Al Haig, Reagan’s first Secretary of State, is described as “Ronnie’s biggest mistake in the first term.” In spite of the fact that Haig identified the foreign-policy objectives of an administration that was almost totally inexperienced in such matters, we learn only that “he was too power-hungry…obsessed with matters of status…had a prickly personality and was always complaining that he was being slighted.”

Bill Clark, another loyalist from California (also of the jump-off-the-cliff kind), “was another bad choice, in my opinion. I didn’t think he was qualified for the job [of deputy secretary of State]—or his subsequent position as national security adviser.” He struck Nancy “as a user…but Ronnie liked him, so he stayed around longer than I would have liked.”

Bill Casey? Poor Bill: if we didn’t have enough to deal with that month, William Casey collapsed in his office.”

Though Nancy Reagan solicits our sympathy about inappropriate public discussion of the president’s digestive system and her own mastectomy, she does not hesitate to gossip about Bill Casey’s fatal brain tumor and to speculate about effect on his mental powers. She suggests, for example, that Bill’s illness may have caused memory loss and bad decisions about the time the Iran-contra diversion was being formulated. Presumably, the fact that her stepfather was a neurosurgeon makes her expert on such matters.

It apparently never registers with the former first lady that writing these views she damages her husband and his presidency. After all, these were Ronald Reagan’s choices, made after close consultation with his financial and political supporters and friends in California; he must have thought that they met his own standards.

She finds difficult to say thank you—a pity because dozens and dozens of able, well meaning, hard-working people were devoted to Ronald and Nancy Reagan and to the country, and served them both well.

Although was not the only Reagan associate to be frog-marched through the media to chorus of falsehood and innuendo orchestrated by anonymous sources who wanted to separate us from the president, my recollection of my bizarre experience is still quite green. So are its lessons. Nevertheless, I want to take this occasion to say that if the “inside” material about everybody else is as full of holes as it is on me, caveat lector!

What we have here are Nancy Reagan’s views of what she thinks happened, or wants us to think happened. It is impossible in a magazine that weighs only a couple of pounds to list all the stretchers, but I offer two:

Mrs. Reagan seems to think that I built a patio for myself at the White House that the government paid for. But that’s not an accurate account.

The patio outside the chief of staffs office is located over a large National Security Council office. Well before I became chief of staff, this secure area developed a leak (the wet kind), and plans were made to fix it. It was decided to renovate the NSC space at the same time, but the existing patio and the president’s patio would have to be destroyed in the process to get at the space below. An architect’s plan to restore both patios and enlarge the president’s was approved by all those then involved, and the actual work didn’t start until months after I arrived at the White House. This vastly expensive project succeeded—and thus became the only instance in the annals of the administration in which a leak was actually plugged.

I did decide to have some chairs and a sofa in my office re-covered and to put in new drapes. Nancy Reagan’s version notwithstanding, I paid for this out of my own pocket. I did not enlarge the office, nor did I use a paid interior decorator. My wife, in fact, chose the fabrics and colors.

I understand it came as a surprise to Richard Nixon that he “called to say that if Ronnie wanted him to talk to Don about resigning, he would.” In her narrative many of Nancy’s calls at that level seem to be incoming, but memoirs and life do not always match perfectly.

As might be expected, I read My Turn with more hindsight and also with a greater sense of anticipation than most readers will bring to it. I was pleased to note, then, that Mrs. Reagan has confirmed the accuracy of every important point in my book, For the Record. Where we differ in our versions of events, it is often though not always (see above) a matter of interpretation.

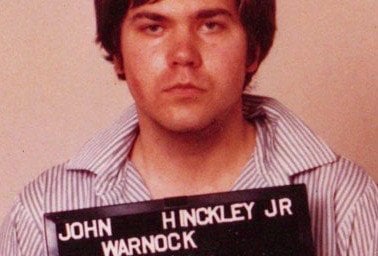

What she cannot understand is why I did it— that is, why I revealed that the president’s schedule and therefore his life and the most important business of the American nation was largely under the control of the first lady’s astrologer. Frankly, I hesitated before putting this astound ing fact into the historical record. I certainly did not “take this information… and twist it to seek… . revenge.”

The fact is, I wrote about astrology because it was an essential truth about the way the Reagans operated.

My description of White House life in my period as chief of staff would have made little sense if I had omitted it. All those schedule changes, when laid out in black on white pages, would have looked downright senseless in the absence of an explanation.

Would that there had been some other explanation—but there wasn’t. Astrology was it. It was a daily, sometimes hourly, factor in every decision affecting the president’s schedule. Nancy Reagan says “unequivocally” that “Joan [Quigley] ‘s recommendations had nothing to do with policy or politics—ever. Her advice was confined to… Ronnie’s schedule, and to what days were good or bad….”

But he—or in this case she—who controls the president’s schedule controls the workings of the presidency. It is the national chart of influence.

Although using an astrologer “never struck [her] as particularly strange,” she concealed her consultations from her husband, the staff (with the exception of Michael Deaver and, later, Bill Henkel and me), and the Secret Service.

What a shock it must have been to the agents, who so carefully guarded the president, to learn that a total stranger—to them—knew not only intimate details of presidential movements but could actually set the time of these moves! Sure iy they would think that posed a security risk. In retrospect, I think the nation owes Ms. Quigley a vote of gratitude. She really seems to have been interested in nothing but astrology. “No body was hurt by it—except, possibly, me,” writes Mrs. Reagan.

***

This self-portrait limns a misunderstood mother/wife/friend, who underneath all the misunderstandings and misinterpretations is loyal and kind and loving—a simple-hearted woman who hungers for affection only to find rejection.

She suggests that the sadness of her private life—the shooting, the bouts of cancer, the deaths of her parents, added to the frustration, controversy, and demands of public life—would drive most people to do and say much more than she did.

“Don’t criticize me . . . until you have stood in my place,” she writes. Many readers may reflect that others have borne similar burdens with less happy outcomes.

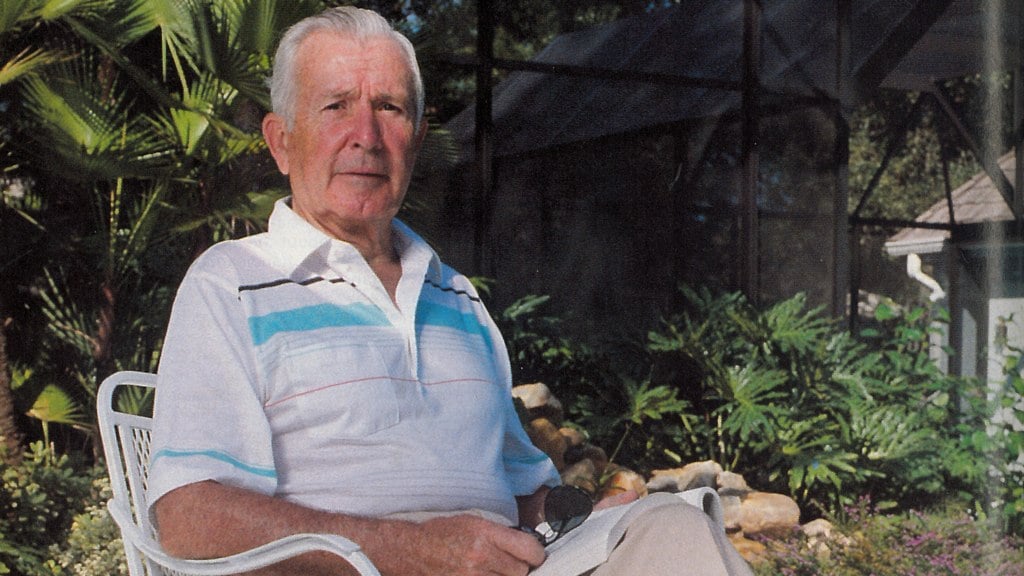

Most people in her circumstances—including, I believe, Ronald Regan—would count their many blessings, put their hurt and fear behind them, and go on with a new appreciation of life. Not all are lucky enough to head west and enjoy their golden years together.

Nancy Reagan and Donald Regan both have written for the historical record. Others will no doubt do the same; and to that end, history, that greatest of all polygraphs, will make its judgment. I am comfortable with that.