The most beautiful thing in Ken Novel’s living room was a grandfather clock he had built himself. But Novel’s masterpiece symbolized the one thing he didn’t have—time. On December 3, 2006, he was told he had liver cancer.

Not long after that, he decided to give his remaining months some meaning. He wanted more people to know about hospice care and what it can offer to patients and those who love them. He agreed to share his final journey with a stranger—me.

We soon discovered we were connected by more than a story. A year earlier, I had asked the Jewish Social Service Agency to find a hospice patient I could follow. It called about Ken right after I returned here from my brother Jeffrey’s funeral in New Jersey.

Jeffrey, 59—about the same age as Ken—died of cancer. There were other connections. Ken and his wife, Theresa, had grown up near Jeffrey and me on Long Island. They were from Floral Park; Jeffrey and I lived in Franklin Square. We were in the same school district. Ken and I spoke the same language—it’s more an attitude than an accent.

Joan de Pontet, then executive director of the Jewish Social Service Agency (JSSA), asked if Ken’s story would be too close for comfort. I said no. I hoped Novel would help me come to terms with what had happened to our family. He hoped I would help people understand what “hospice” means.

Ken Novel was a hairstylist and part owner of O Salon in Georgetown. He loved his family, his work, and Washington. He had gone to beauty school after serving in the Army in Vietnam. He came here from New York in 1970, and the first salon he opened was Hair Inc. in Georgetown. A brief marriage ended in divorce, but he stayed friendly with his ex-wife and close to his daughter Lisa.

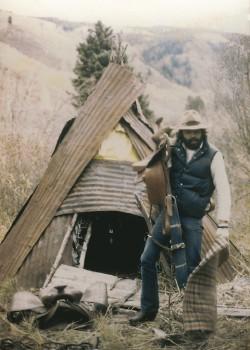

In 1974, Novel went to Colorado for Christmas. He stayed nine years. In Aspen, he met hairstylist Theresa Berrent, and it was love at first sight. They married in 1983.

It was only after 17 years of marriage, when they went back to Ken’s childhood home in Floral Park, that they realized they had known each other as children. From his bedroom window, he could see her old apartment.

“We met when I was four years old,” Theresa says. “He was the big kid who wrecked my lemonade stand.

“Our lives kept intersecting. In Aspen, I was dating his best friend and he was dating mine.”

A daughter, Simone, was born in Aspen. The family moved back to Washington because Ken’s parents and brothers lived in this area. Their son, Anthony, was born here. Seven years ago, Novel opened O Salon with his brother Robert and two other partners.

Novel had always been healthy. He’d started playing golf as a kid when he caddied at the Bethpage golf course about half an hour from Floral Park. When he and Theresa lived in Colorado, they skied daily.

In recent years, he’d had some pain radiating from his chest into his right shoulder. He consulted his doctor, but the pain was intermittent and the doctor found nothing wrong.

Ken and his brother Gene went to New York for a family funeral in November 2006, and Ken had stomach cramps there. The pain worsened, then subsided. Back home at Thanksgiving, he felt too sick to eat. His son drove him to the emergency room at Shady Grove Adventist Hospital. He was there 11 days. Most of the time, he drifted in a fog of pain medications. Shady Grove doctors told the Novels they suspected Ken had a blood clot blocking the portal vein of his liver.

Several conditions can cause this kind of clot, including an inflammation of the bile ducts, pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, and liver cancer. The Shady Grove doctors referred Novel to the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center at Georgetown University. A blood clot sounded treatable.

Novel left O Salon around noon to go to the nearby Lombardi Center to get the test results. He had scheduled two clients for later that day. He told Theresa—a stylist at New Wave Salon in Rockville—she didn’t need to come along.

The Lombardi oncologist told Novel that one of the blood tests showed a high level of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)—a marker for cancer. Normal levels of AFP are under 10; Ken’s count was 1,000. Imaging studies showed a tumor in the liver. Novel had what was called heptacellular carcinoma.

He called his brother at the Georgetown salon and said, “I got bad news. I’m not coming back.”

“You mean this afternoon?” Gene asked.

“Ever.”

Ken drove home to wait for Theresa. He didn’t want to break the news by phone.

“I called him because he didn’t call me,” Theresa says. “I knew right away from his voice.”

For three days, the Novels waited to find out if Ken was a candidate for a transplant. They were optimistic—he was relatively young and in good shape, and he wasn’t a drinker. But the Georgetown transplant committee said no. Because of the extent and location of the cancer, he wasn’t a candidate for surgery or a transplant.

The doctors offered chemotherapy. The best drug for treatment of Novel’s cancer cost $1,000 a week, and there was only a tiny chance it would shrink the tumor.

My brother, Jeffrey, was a chiropractor who spent his life studying medicine. He had difficulty breathing and a cough; he thought he had pneumonia. He never considered lung cancer because he didn’t smoke. Our family has a history of heart disease and diabetes—but not cancer.

In fact, lung cancer among nonsmokers is on the rise, and genetic predisposition is overrated as a cancer predictor. Just ask all the women who are the first in their families to develop breast cancer.

Before he got sick, my brother thought chemotherapy was a blunt instrument that had a greater chance of making him miserable than of making him well. He said he’d never do it. He advocated herbal remedies. But when he was fighting for his life, he was willing to use any weapon he could. He took his herbal remedies—but he took chemotherapy, too.

So did Ken Novel. Despite the long odds, he returned to Lombardi for six weeks of chemotherapy. He lost 30 pounds, but the tumor grew. Doctors at Lombardi told him, “We have nothing more we can do for you.”

Those words infuriate Dr. Perry Fine, a pain-management specialist who has become an expert on hospice and palliative care: “Hope is extraordinarily important. We have to redefine hope—it can’t be seen strictly as immortality.”

Most people—even many physicians—associate care with cure. Agreeing to hospice or palliative care can feel like a betrayal of someone you love. In fact, palliative care can involve a lot of active disease treatment, including chemotherapy or radiation aimed at shrinking tumors to alleviate pain and other symptoms. The goal is to enable people with terminal illnesses to be up, about, and getting the most out of their lives.

Novel’s initial reaction to hospice was typical: He equated it with abandoning hope. “I didn’t want to go to hospice,” he said. “It’s the final place.”

A few weeks went by, and he started talking to people who knew about hospice. He learned he wouldn’t have to go anywhere—hospice would come to him. Most patients receive services at home or wherever they happen to be. Few are admitted to a special hospice facility.

Washington’s most famous hospice patient, humorist Art Buchwald, did move into the Washington Home and Community Hospices, a rehabilitation and long-term-care facility that has a section devoted to hospice patients. But of the more than 800 patients treated on any given day by Capital Hospice, the largest in the Washington area, only 15 are in the program’s inpatient facility.

Novel was told he could be a hospice patient and, if he improved or if a promising new treatment emerged, be discharged from hospice and readmitted later. In the meantime, hospice would deliver medications to his home; send a nurse to check on how he was doing with sleep, appetite, and pain; give him a monitor to wear to summon aid if he was in physical trouble; and send volunteers to help or keep him company.

Hospice would make it possible for Theresa to keep working. A hairdresser relies on her client base, she says: “If I’m not there for two haircuts, they’ll find somebody else.” Ken also wanted to spare Theresa as much as possible from being his full-time caregiver. And because Medicare largely covers hospice care, the financial burden on the family would ease.

Although he wasn’t Jewish, Novel signed on with the hospice program of the JSSA in Rockville.

I met Novel at his Gaithersburg home in April 2007. He had been discharged from hospice a month earlier to undergo a new treatment at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. Interventional radiologists had developed a technique called chemoembolization to inject chemotherapy drugs directly into a tumor. It’s not a cure, but according to the Society of Interventional Radiology, 70 percent of patients improve. The treatment can relieve pain and other symptoms; some patients may live longer.

In Novel’s case, the chemoembolization killed 25 percent of the tumor in his liver. He was readmitted to hospice once he came home from Johns Hopkins.

The week after the procedure, Novel slept 20 hours out of 24. He was doing better by the time we met—alert and eager to talk. We sat in his sunny living room on a spring day, but he was wearing layers of clothing and a hat because he felt cold all the time. “I sleep with four blankets,” he said.

I started to shiver. My brother, Jeffrey, was a bear of a man, a human furnace who wore shorts in the middle of winter. His weight and hair loss from chemotherapy were not as shocking to me as the sight of him bundled up in blankets.

By April 2007, Novel had been living with his diagnosis for six months. “They told me I’d be dead by now,” he said.

After the chemoembolization, his pain decreased. “Some days, the quality of life is great,” he said.

On the good days, Novel hated that his doctor wouldn’t let him drive because of his medications. The Novels had sold his car. Theresa would find Ken on Craigslist looking at motorcycles and classic cars.

He was trying to stay positive. “Lots of things are good,” he told me. “You find out how close you and your family are.”

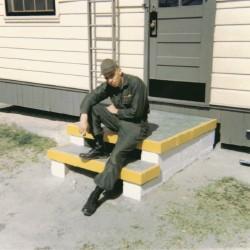

He was bemused to discover that being a patient was a full-time job—with doctors’ appointments, therapy, recovery, and visits from his nurse, his social worker, and others, he was always busy. He also found himself thinking again about Vietnam, where he had served in the 101st Airborne Division stationed in Quang Tre: “Every time you went anywhere, you wondered if it was your time to be killed. It wasn’t something you ever got used to.”

Novel was injured in Vietnam and sent to a hospital in Japan. He remembered a colonel coming into the ward, going down the line of beds one by one, picking up the charts and saying, “You go to the States. . . . You stay in Japan. . . . You go back to your unit.”

It felt like a lottery. Novel didn’t know how to react when he was sent back to the States. “I have that same feeling now,” he said, “that I had in Japan.”

As soon as he enrolled in hospice, the agency put together a team for the Novel family. Sylvia Glaser has been a JSSA hospice nurse for 20 years. A silver-haired sprite, she’s reluctant to tell people she’s a hospice nurse. They ask, “Isn’t it depressing?”

“I get to meet the most incredible families,” Glaser says. “It has renewed my faith in people.”

She lives a few streets away from the Novels. They have the same house number and sometimes get each other’s mail. Glaser used to go to Curves gym with Theresa, and she was reluctant at first to take Novel’s case—she never wanted to take care of friends. But Theresa wanted Sylvia.

“We’re not religious, so who do you go to?” Theresa asks. “When I met Sylvia, I felt so comfortable. I needed to have somebody.”

Glaser came to Novel’s house once or twice a week. At first, she did more talking than treating. She would ask Novel about his appetite, his sleep, his pain. She would check his pulse and blood pressure. She would ask about short-term memory loss—a side effect of some drugs. She would keep track of his medicines and check in with his doctors.

“We get them off a lot of medicines,” Glaser says. “Less is better.” Many patients take a number of drugs prescribed by different doctors and actually do better when some of their medications are eliminated.

Serious illness doesn’t happen just to an individual; it happens to a family.

“I call it ‘our’ cancer because we all have it,” Theresa told me.

Social worker Ellen Lebedow sees her JSSA job as helping family members say things that are hard to express.

Before Ken got sick, he and Theresa had never been apart. Because he was nine years older, Ken felt protective of his wife. There was no way he could protect her from this.

Now Theresa had to hold the family together. Although all of her clients knew about Ken, she didn’t talk about his illness at work. But the stress weakened her immune system, and she developed pneumonia. She kept going to work.

Lebedow explained to Novel: “Theresa needs to be doing something. She likes to fix things, but she can’t fix you.”

Simone and Anthony also felt the burden of the illness. “My kids know the full facts,” Novel said. “They were raised to handle things head-on. They know I’m dying, but they don’t dwell on it.”

That’s what they told him. Ken had always played a big role in his children’s lives. “You knew it was serious when Dad stepped in,” Simone says. The idea that he wouldn’t be there was devastating. She was calling him three or four times a day. She and Anthony were constantly trying to get things for Ken to save him steps or make him comfortable.

Theresa and Simone could talk and cry together, Lebedow found. Anthony wasn’t a talker. According to Lebedow, Anthony found release in his music and his art.

As the months passed and Ken got sicker, Theresa, Simone, and Ken turned to Lebedow often. Ken felt a sense of urgency—his kids were too young for him to leave them. Simone was studying for a master’s degree in social work. It had taken Anthony a while to figure out his future, but he was now committed to attending Montgomery Art Institute in the fall. Said Novel: “I want to see them through college.”

A few months after he got sick, Novel decided to transform his basement workshop into an art studio for Anthony. Tony Kropf, a retired financial-services specialist and hospice volunteer, came over to help.

Kropf had gone through 12 weeks of hospice training—learning about diseases and how to deal with the emotions of hospice patients. He admits he has had a hard time dealing with some patients with Alzheimer’s disease. “It’s hard to communicate,” he says. That was no problem with Novel.

The two men started out moving lathes and saws, but whenever Novel felt up to it, they ventured farther afield. One day they went to a classic-car dealership, and Novel took a car around the block for a test drive.

Rabbi Judith Brazen became part of Novel’s hospice team. Every hospice program offers chaplains of different faiths who provide spiritual comfort for patients and their families if they want it. Novel’s family didn’t feel the need for support, but he did.

Brazen tries to follow whatever beliefs patients and families have found meaningful. She looks for rituals that have given them strength and peace. Sometimes that involves healing old family wounds. A lot of times, people want to talk about the possibilities of a hereafter.

“When medical hope is no longer feasible, I offer a different kind of hope, a hope that extends the meaning of our finite lives,” Brazen says. “We can find ways to express appreciation for the joys they’ve experienced and lives they’ve lived even in the face of loss.”

Novel felt a spiritual connection with nature, Brazen says. One of the passages he loved was by Terry Tempest Williams:

I pray to the birds.

I pray to the birds because I believe they will carry the messages of my heart upward.

Last June, Novel had his second chemoembolization at Hopkins. This time, his reaction was more severe. He had hiccups for five days and couldn’t sleep. The drugs he took to help with the hiccups caused him to hallucinate. “I thought ants were crawling all over me,” he said.

As the illness progressed, his hospice team grew to include home health aides. He needed help with bathing, dressing, and moving from one level of the house to another. But he was making the decisions. He could recognize the signs that he was in for a bad day or week. He could tell within 20 minutes whether his pain would be severe enough to require liquid Atavan to supplement the morphine.

Novel always expected to bounce back from these episodes—and for months he did. I would get a call from someone on the hospice team telling me things were looking bad, and by the time I got out to see him, he was sitting on his living-room couch telling me he’d been out on the golf course. That spring Novel made it to Rehoboth, where the family has a little modular house. One of his neighbors had been Mr. Wilmington 1949, and he now offered to give Novel bodybuilding advice.

One of the challenges for a patient’s family is the out-of-character behavior that a combination of drugs and disease can cause. In September last year, Ken Novel ran away from home.

A client had given Theresa a bottle of Merlot to celebrate Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish new year. She drank a couple of glasses with dinner, gave Ken his medications, went up to their bedroom, turned on the TV, and fell asleep. When she awoke at 9:30 pm, Ken wasn’t in bed. He was spending his days in a hospital bed in the den, where he could look out at the birds he loved, but at night he went upstairs to their bedroom.

Theresa called out to him, and he responded, “I’m online buying a car.”

Ken then packed a bag and walked out of the house in his pajamas.

Theresa called Sylvia Glaser in a panic. “What do I do?” she asked.

“Follow him,” Sylvia said.

Anthony had just gotten out of the shower. By this time, his father was blocks away. Barefoot, Anthony grabbed his cell phone and ran after him. Theresa followed, then doubled back to get the car.

She pulled alongside Ken and tried to get him into the car. Anthony urged her to go home. Her talking only seemed to make Ken angrier. Then the car died.

“Anthony, go home and call AAA,” Novel said. Finally, Anthony persuaded his father to go home. A hospice aide was there to help him get settled in.

The tow truck arrived at 10:30. By 11:15, Novel was quiet. The hospice aide left, but Theresa couldn’t rest. “I was still so mad,” she says. She heard a knock at the front door. It was a neighbor in her nightclothes asking if she could talk to her. Theresa didn’t know the neighbor’s name.

“I know you’ve been having a hard time,” the neighbor said and handed Theresa a check for $2,000.

Six years earlier, the neighbor’s house had been ransacked. The Novels noticed strange cars near the house and wrote down the license-plate numbers. Later they served as witnesses in court. But the two families had never talked again about the incident.

“I never said thank you,” the woman told Theresa.

Two weeks later Novel told me about that night: “I felt alone. As much as people are all around giving me so much attention and love, I still felt so alone.”

His liver was failing, and he had the beginnings of jaundice. He hadn’t wanted the hospital bed he was lying in. He had hoped he would still get some exercise.

A week later, Novel played 36 holes of golf. “It was a short course,” Sylvia Glaser said, “but they charged a flat fee, and he wanted to get his money’s worth.”

The neighbor’s check inspired Novel. He started talking about setting up a fund to send medications to developing countries where they’re unavailable or too expensive. Each time Novel’s doctors changed his medications, he had untouched boxes and vials at home that were thrown away.

His frustration with his cancer had eased. “I’m happy I have another day,” he said.

A week earlier, Novel’s oncologist had called to say a chemotherapy drug that hadn’t been approved to treat liver cancer when Novel was diagnosed was available. If Novel elected to have the treatment, he would have to be discharged from hospice.

He said no. Hospice had become his family. Besides, he was working on a project—a cowboy toy chest for his grandchildren, Jake and Luke—and he wanted to finish it.

Novel grew weaker in October. Some days he slept 23 hours. Another day, he was up for a ride around a nearby park. He’d be confused one day, alert the next.

“He monitored his pain medications himself,” Glaser says. “He wasn’t taking much. It was important for him to be in control.”

Novel wanted to plan his memorial service. He asked Rabbi Brazen to conduct it. His appetite decreased and he looked gaunt, but he talked to Ellen Lebedow on October 29. He dictated a letter to be read at his service.

A few days later, frustrated that he wasn’t strong enough to walk alone, Novel got up anyway and fell. When Glaser arrived, he was in bed, eyes closed. “The soul is strong,” he told her. “I’m at peace.”

On November 11, he wouldn’t wake up. Glaser rushed over. “He opened his eyes, and he said my name,” she recalls.

Novel upped his morphine. Brazen visited on November 13, and he could answer her questions. That night he said he felt very cold; it took more morphine to combat the pain. The next day, at age 59, he stopped breathing.

Hundreds of people came to Novel’s memorial service at Bradley Hills Unitarian Church. There were friends, family, clients, and fellow hairdressers. One of Novel’s longtime clients, journalist Ted Koppel, came. Several of Novel’s colleagues whispered about Koppel’s great hair.

Three people spoke at the service—Novel’s brother Gene, Rabbi Judith Brazen, and Ellen Lebedow.

Hospice professionals say that the hardest part for a family is “the conversation.” Talking about hospice is an admission that their loved one isn’t going to get better. Both patient and family try to spare each other, says Capital Hospice’s Marlene Davis. Often the living room becomes the sick room. Davis will arrive to find relatives whispering in the kitchen so the patient can’t hear: “ ‘Don’t tell Mom she’s dying,’ they say. Then I go to the living room, and the patient says, ‘I know I’m dying, but don’t tell my children.’ ”

Maintaining a “fight to the finish” mentality is sometimes fostered by the patient’s doctors. There’s a joke they tell in oncology circles: “Why are coffins closed at funerals? So the doctors can’t continue the chemotherapy.”

As a result, many families that could benefit from months of hospice care turn to it only for the last dying days.

That’s what happened with my brother. He and his family had joined my family for a vacation at Bethany Beach in August 2006. When he arrived, it seemed clear he was sick. He had a hard time breathing, and his legs were swollen. He hadn’t been really well for a while—heart problems, high blood pressure, diabetes. On the third day, I got him to go to a nearby walk-in clinic. He gave in so that he could get the antibiotics he thought he needed for his self-diagnosed pneumonia. The ER physician found a collapsed lung and blood clots in his legs. She insisted he go to the nearest hospital by ambulance.

The doctors at Beebe Medical Center in Lewes drained his chest to reinflate his lung and increased his blood thinners to deal with the clots. When the lab results came back, he found out that the fluid in his chest contained cancer cells. It was adenocarcinoma.

Jeffrey lived in northern New Jersey, near the Delaware Water Gap. For the next seven months, I made the trip between Washington and New Jersey often. But the burden of Jeffrey’s care fell on his wife, Joyce. She had to put together a network of friends and family to decode doctors’ bills, handle household repairs, stay with Jeffrey when he couldn’t be left alone, and do other things needed to keep the family going.

I wish we had known more about hospice. I wish I’d had the courage to raise the issue with Jeffrey. He was stubborn, but I was his big sister.

After a patient dies, the JSSA hospice team spends the first part of its weekly staff meeting talking about him or her. Members light a candle, say a prayer, share memories.

Novel was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Rabbi Brazen officiated. It was a first for her at Arlington. It was a first for the military chaplain, too—he had never met a female rabbi. Novel would have loved that.

Ellen Lebedow read her eulogy from the memorial service: “About ten months ago, my colleagues and I were welcomed into Ken and Theresa’s lives. We found a man with his arms open—open to accepting our support, open, at such a dark time, to finding glimmering moments, open with his boxing gloves on, ready to fight for every sacred moment he could share with his family. What we learned from Ken was that he needed our assistance in order to get busy living his life. Spending time on a motorcycle, on the golf course, at the beach, in his workshop, and, most importantly, with his treasured family. . . .

“Ken’s open heart allowed him to feel blessed in his life, and he discussed this feeling often. . . . . What he focused on near the end of his life was not self-pity but how he could leave a loving legacy for those he held dear.”

He left a final gift for me. He showed me how to die well and to leave your loved ones with the comfort that you rest in peace. I know Ken Novel does. I hope my brother does, too.

What to Know About Hospice Care

Once a patient and the family have determined that an illness can’t be cured and that likely life expectancy is six months or less, the patient’s doctor can certify eligibility for hospice care.

If the patient improves, goes into remission, or decides to resume curative treatment, hospice can discharge the patient for readmittance at a later date.

Hospice covers more than pain management. Radiation, chemotherapy, and other treatments designed to alleviate symptoms are often part of a hospice plan.

Most patients are treated at home. Hospice usually assigns a team to work with the patient’s doctor. Medicare requires that hospices provide doctor services; nursing care; medical equipment and supplies, from hospital beds to bandages; drugs for symptom control and pain relief; short-term care in the hospital to provide respite for caregivers or to manage pain and symptoms; home health and homemaker services; physical, occupational, and speech therapy; social-work services; dietary counseling; and grief counseling.

Most hospices have volunteers and clergy available for spiritual counseling. A hospice worker is on call 24 hours a day.

Medicare covers nearly all the costs of these services. Most health-insurance plans include hospice coverage.

Not all hospices are the same. Some are for-profit, others nonprofit. Some are affiliated with a hospital or nursing home. A hospice should be Medicare-certified as well as licensed by the state or local jurisdiction. Information about hospice care is available at the National Hospice and Palliative Care Association’s Web site, nhpco.org, and on Medicare’s site, medicare.gov.

Hospices serving the Washington area include these:

Capital Hospice (703-538-2065 or 800-869-2136; capitalhospice.org) serves DC, Northern Virginia, and Prince George’s County.

Hospice of the Chesapeake (301-499-4500; hospicechesapeake.org) serves Prince George’s and Anne Arundel counties.

Jewish Social Services Agency Hospice Services (jssa.org). For DC and Maryland, call 301-838-4200; for Northern Virginia, 703-204-9100.

Montgomery Hospice (301-921-4400; montgomeryhospice.org) serves Montgomery County.

Washington Home and Community Hospices’ areawide inpatient facility is at 3720 Upton St., NW; 202-895-0121; thewashingtonhome.org.

Have something to say about this article? Send an e-mail to editorial@washingtonian.com and your comment could appear in our next issue.

This article appears in the August 2008 issue of Washingtonian. To see more articles in this issue, click here.