This is the story of how Michael Jackson—the King of Pop and at the time one of the world’s most wanted men—hid out at my family’s house.

Among his staff, Jackson was referred to as the Principal. In our family, he was known as the Secret—one we kept for nine days five years ago. We believed then, and do now, that not revealing Jackson’s whereabouts was the right thing to do. Now that he’s gone, I can tell why and how we did it.

It was March 2004. The previous year, Jackson had appeared on TV explaining why he believed it to be normal for adults to share their beds with children, that it was the most loving thing you could do. What he saw as innocent a Los Angeles district attorney saw as criminal. Rumors were swirling that Jackson would be indicted on charges of child molestation by an LA grand jury. The King of Pop became a subject of ridicule. Gone was the cute boy who had swooned his way into the hearts of generations. He was replaced by a man-child, a suspected pedophile.

In April 2004, Jackson was to receive an award from the African Ambassadors’ Spouses Association for his humanitarian work. But few of the journalists seeking credentials for the event cared about his work in Africa—they wanted to ask him about what had happened at Jackson’s Neverland Ranch. So a routine trip to Washington became anything but routine. Jackson needed a place to stay, and those closest to him were finding that there was no acceptable room in a Washington hotel.

The real-estate agent assigned to locate lodgings for him was running out of options. Stopping for a bite to eat, she saw the April 2004 Washingtonian. It featured a “Great Places to Live” article with me, my wife, and our two children on the cover. The story talked about how we had designed a house near Leesburg with no walls and plenty of open space. The agent knew us well enough to pick up the phone and ask whether we’d consider allowing Michael Jackson and his children to stay in our home.

What would you have done if a friend had called out of the blue and suggested that Michael Jackson might be interested in staying at your home? We first assumed she was joking. But she was serious.

On the previous Sunday, the sermon delivered by our minister, Reverend Dr. Norman A. Tate, had been about the Good Samaritan. Reverend Tate was the first person we consulted. Should we offer Michael Jackson safe haven? That night, following a lengthy family discussion and vote, we ironed out the details and began preparing for the Jackson family’s arrival.

Michael Jackson traveled with an entourage of 14. There were two cooks, three nannies, three children, personal assistants, tutors, security men, and Jackson himself. He moves in, you move out. (We stayed at a hotel.) Those who surrounded him called him the Client or the Principal. Rarely was he referred to by name. There were stretch Hummers and Suburbans that suggested a visit by a head of state—which is what our neighbors suspected.

Before he moved in, the house had to be prepared. His entourage covered all glass windows and doors. He was to have white bed linens and towels only. His favorite scent, a mountain fragrance, was sprayed everywhere and lingered for weeks after his departure.

Then, under the cover of darkness, he arrived. His private jet flew in and out of the Leesburg airport.

That evening as he moved in, we dined at a local restaurant, courtesy of the entertainer, and wondered whether he was enjoying our house as much as we did. We wondered whether he admired the views of the Blue Ridge Mountains from the deck and whether he took a stroll and noted the seven species of birds that call our acres home. Did he play the baby grand piano? Did his children frolic in the small dance studio? Would he enjoy the pool and hot tub and five acres, or would he just hole up and hide?

The next morning brought invitations for us to attend several events, including a BET reception and the African ambassadors’ reception.

Before Jackson’s arrival at the BET affair, a who’s who of Washington’s African-Amercan elite waited patiently. There were plenty of nasty remarks; some couples talked about how they wouldn’t let their children anywhere near Jackson. Then he arrived and the stampede began. Those who had ridiculed him the most were first in line.

His assistant ushered us to the front of the receiving line. We were told Jackson wanted to meet us first to thank us for allowing him and his children to use our home. He talked about the family pictures on the walls and how comfortable the place felt.

It was all very pleasant, but you could tell there was something unsettled about him. You could tell what he coveted most: He’d grown up without a childhood, and our house is filled with the kind of childhood memories money can’t buy—baptisms, first-birthday parties, family adventures.

To keep his stay at our house secret, we arrived there in the morning in time for the school bus to pick up one of our two daughters. We were always met by one of Jackson’s bodyguards dressed in all black. I finally told him that if he wanted Jackson’s presence to remain secret, he shouldn’t meet us every morning looking like Mr. T.

Reporters were in high gear searching for Jackson. We feared a media circus in our neighborhood. Our daughters, then 13 and 15, went to school each day wondering if their world would unravel.

On day eight, we were surprised Jackson wasn’t ready to leave, as the agreement had called for. That night, he arranged for a private wine-and-cheese reception at our own house so our children could meet his. He was more than gracious. While I worked, my wife and daughters were greeted by Jackson and his three kids. They spoke of childhood and normality. His children were very talkative; he was soft-spoken but playful. My wife described him as a gentle soul who obviously loved his children and they him. He also was willing to discipline his kids. He posed for pictures and agreed to autograph many things, including CDs.

By day nine, Jackson and his children were gone.

The empty wine bottles hidden around the house hinted at a man we now know was deeply tormented. There were other signs, but my wife and I have agreed they will remain secret. We knew from his representatives that Jackson tended to live nocturnally, sleeping during the day and roaming the house at night.

A visit by guests to our house now always leads to a conversation about Jackson’s visit. His picture, taken when he was standing by our baby grand piano, sits atop a table in the living room. Almost everyone sees it and wonders what it was like to talk to him and have him live in our home.

I’m always asked why I’ve never talked about Michael Jackson’s stay at our house. I say I met Jackson three times in my life—twice face to face.

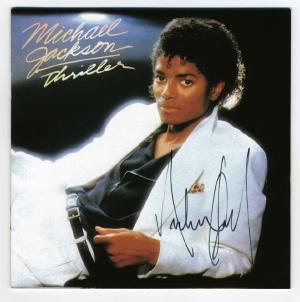

Most African-Americans of my generation were introduced to a young Michael Jackson through the radio or by a friend who had one of his records. For me it was a 45-RPM played at Sonny Mason’s barbershop in my hometown of Wheeling, West Virginia.

The second encounter was in 1984 when Jackson and his brothers kicked off their Victory Tour in Kansas City. I stood out among the other reporters covering it because I didn’t appear to care about Michael Jackson the celebrity as much as I did the revenue the tour represented in the cities it visited. That night, I received two tickets to attend the concert and a private reception at Kansas City’s Arrowhead Stadium. In a receiving line for the Jacksons following the concert, I met Michael in person for the first time.

The third time was the Washington visit.

I, too, wonder why I’ve never talked before about his stay in our home. Was it because Jackson and I were the same age or the fact that, like so many African-Americans, I liked to remember the little kid from Gary, Indiana, more than I did the man with another reputation?

Perhaps, as Reverend Tate suggested, it was just the right thing to do.

As word of Michael Jackson’s death on June 25 spread, my family mourned the man we’d met not as the King of Pop but as a person trapped inside a world that was and was not of his own creation, a man who came to us through his representatives in need of a place to stay. As I sat on our deck and looked west toward the Blue Ridge Mountains, I hoped he now was seeing what I see each and every night—a perfect sunset.

This article first appeared in the August 2009 issue of The Washingtonian. For more articles from that issue, click here.