Three years ago, Robert Allbritton flew his executive team to Oklahoma City to kick the tires on a pair of television stations. The New York Times Company had put nine TV stations up for sale, including the two in Oklahoma, and Allbritton was preparing a bid.

Aboard his Citation Sovereign airplane were Allbritton Communications president Fred Ryan, chief financial officer Stephen Gibson, general counsel Jerald Fritz, and marketing chief James Killen. Robert Allbritton is chairman—and pilot.

The Times Company was beginning to feel pressure from print’s loss of advertising revenue to digital media, so it wanted to cash out of television. Allbritton Communications seemed an ideal buyer. Cash-rich at the time, it owned eight TV stations, led by WJLA, its flagship ABC affiliate in Washington, and NewsChannel 8, a cable station here.

The question on Allbritton’s mind: Do you want to put a big bet on something you already have a big bet on?

Allbritton was 37 at the time. Boyish and easygoing, he was sometimes mistaken for a reporter or techie in the newsroom. He had been running the family communications business since 1996, when he was four years out of college. His father, Joe Allbritton, had been a big player in Washington business and political circles since coming from Texas in 1973; he entered the media market by buying the old Washington Star and Channel 7, and he took control of Riggs National Bank.

“A Texan with a Washington footprint big enough to rival the Lone Star State” is how the Washington Business Journal described Joe Allbritton.

By the time of the Oklahoma trip, the family had sold Riggs Bank under the weight of a money-laundering investigation. Joe, in his eighties, was retired but still a force, and Robert was running things.

The company’s top executives had been examining the TV deal for weeks. They were eager to bid. Back at company headquarters in Rosslyn, Robert Allbritton analyzed spreadsheets and crunched the numbers. He asked his accountants to boil the deal down to one page, got into his blue Mini Cooper at the company headquarters in Rosslyn, and drove across the Potomac River to his parents’ home on Foxhall Road in DC.

There he sat down to lunch with his father, Joe, and his mother, Barbara. Paintings by Impressionist masters hung on the walls. He had spent his teen years there, holed up in his room with friends working on computer programs, playing tennis, and swimming in the back yard. Today chicken salad was on the menu, as usual.

“What do you think we ought to do?” his mother asked.

“Are they good stations?” his father asked. “Are they in strong markets?”

Robert explained the pros and cons, the debt they’d have to assume, the cost to the company in time and energy.

“What’s our bid going to be?” his father asked.

“I wouldn’t do this thing,” he told his parents.

They were surprised and a little disappointed but respected his judgment. He returned to Rosslyn and met with the team that had flown to Oklahoma City.

“Okay, boss,” one said. “What’s the bid?

“We’re not bidding,” Allbritton replied.

“At any price?”

“No,” he said. “I’m just not comfortable with it.”

Deciding not to buy the nine television stations from the New York Times Company was a crucial decision for Allbritton—and for the DC news business. It freed Robert Allbritton to devote his time and money to launching Politico, the hard-charging newspaper and digital publication that covers political news from Capitol Hill to the White House.

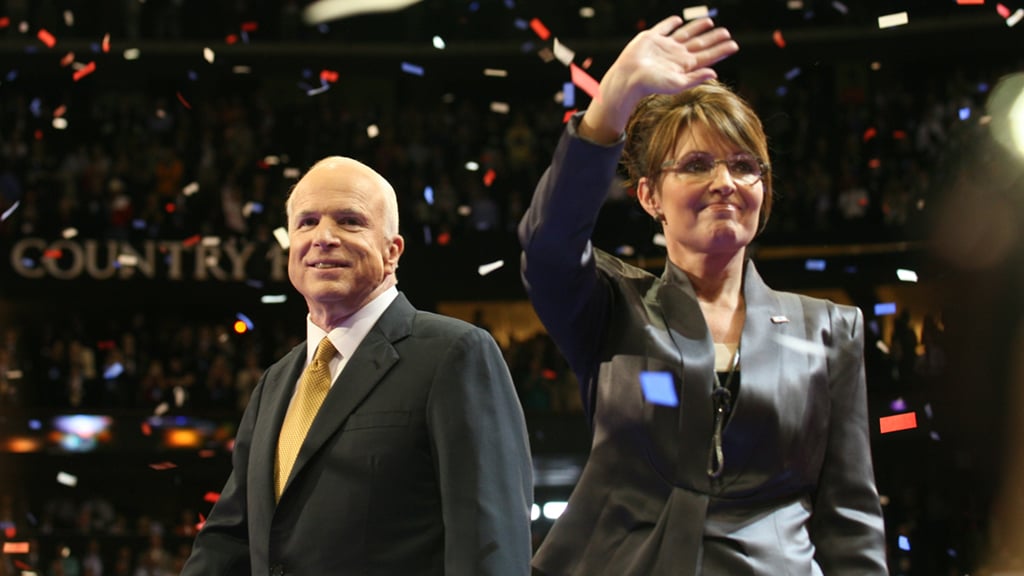

First published in January 2007, Politico has become something of a media phenomenon. Seeking to bridge the gap between print and digital news, it has hired many top journalists and broken more than a few stories. According to Allbritton, it’s a financial success in an industry littered with bankrupt newspapers.

“We are making money,” Allbritton says. He continues to pay top dollar for top journalists. “We’re playing with house money.”

He and I are sitting in his office on the 27th floor of a Rosslyn office tower that once housed the Gannett media company and USA Today. The view reaches from Bethesda to Prince George’s County. Theodore Roosevelt Island is in the foreground, the White House, Washington Monument, and Capitol just beyond. The Potomac River curves below. Eagles float on thermals. Allbritton can look down on helicopters banking past the Kennedy Center.

“I’ll take it,” he says of the view.

Despite his prominent role in Washington, little is known about the man who has controlled two local TV stations for more than a decade and was at the helm of Riggs Bank in its final days. Now, as publisher of Politico, he’s taking on a more public role. He has welcomed audiences to Politico’s presidential debates, hosted eight Politico tables at the White House Correspondents’ Association dinner, and assumed his father’s place at the Gridiron and Alfalfa club dinners.

In a series of interviews, Allbritton makes clear that he doesn’t relish the limelight.

“I just want to be able to shop at the grocery store and not have people know I am anything more than an average guy buying tomatoes,” he says.

He rarely wears a tie, often dresses in jeans, and bows to style only with a pair of Gucci loafers. He doesn’t use a Montblanc pen or sport a Rolex. In fact, he doesn’t wear a watch. Tall and thin, the boss seems to have a smile or good word for everyone. “A puckish sense of humor” is how Mike Allen, one of his marquee journalists, puts it.

But Politico executive editor Jim VandeHei says: “Robert has vision, balls, and money—and knows how to use all three.”

It will be harder to keep his sense of humor and low profile. Politico reporters are breaking stories and rattling the capital: Allen’s exposé about the Washington Post’s proposed “salons”—at which lobbyists would pay to dine and dish with reporters—killed the plan and scalded publisher Katharine Weymouth.

Moody’s Investors Service recently put Allbritton Communications on its “bottom rung” list and gave its outlook a negative rating.

Concerned? Allbritton makes a circle with his thumb and forefinger. “Zero,” he says. “I am very comfortable that we are not going to default on any of our debt.”

Robert Lewis Allbritton was born in Houston on February 16, 1969.

His father was by then a millionaire many times over. Joe Allbritton grew up in D’Lo, Mississippi, and then moved west to Texas with his family. As a young man, Allbritton bought and sold land. He invested profits in banks, insurance companies, and a chain of mortuaries. He was a millionaire by age 33. He declined to be interviewed for this story.

Joe Allbritton was a bachelor into his early forties when he married Barbara Balfanz, the daughter of a pharmacist. Robert is their only child.

When Robert was seven, the Allbrittons pulled up stakes and moved to a house in Georgetown. Joe bought the Washington Star and WMAL-TV, the ABC affiliate, in 1974 for $35 million. Four years later, he sold the newspaper to Time Inc. but kept the television station. Using his initials, he changed the call letters to WJLA. He also bought a horse farm in Upperville, Virginia, and began breeding racehorses. He befriended Presidents.

Young Robert had a front-row seat.

“My dad was one of those guys who always said, ‘C’mon, listen in. Be a part of this. You might learn something.’ He was incredibly inclusive.”

Friends came to sit around the dinner table and learn by Joe Allbritton’s Socratic method. “I learned by osmosis how to deal with people, what was a good risk, what was a bad risk,” Robert says. “I had to pass pop quizzes.”

The Allbrittons sent their only child to the city’s best private schools: Beauvoir, St. Patrick’s, St. Albans.

“Mom carpooled,” he says.

Robert says team sports were not his thing. He was always more interested in technology. As a young teen, he became friends with John Dickerson, whose parents, Nancy and Wyatt, were close with the Allbrittons. “We were into personal computers before personal computers were cool,” Robert says.

John Dickerson, now chief political correspondent for the online magazine Slate, says he spent hours closeted with Robert in the Allbritton home “buried in our computers, doing parallel programming.”

They were so adept that Atari invited them to join its youth advisory board and flew them to a convention in Los Angeles. The Allbrittons took Dickerson to their ski lodge in Snowmass, Colorado. “They were incredibly generous people,” he says.

In the late 1980s and early ’90s, Allbritton attended Wesleyan University, known for its liberal activism. Students protested apartheid in South Africa, among other things.

“I was not politically active in college,” Allbritton says. “It was not in my heart.”

When students demonstrated and some were arrested, Allbritton pulled up a lawn chair, popped a beer, and watched.

He graduated from Wesleyan in 1992 and went directly into Riggs Bank’s investment-management side. At 22, he was analyzing deals and helping the bank decide on loans.

“I was bored to tears,” he says. “I spent much of my time watching the sweep hand reach 5 o’clock.”

He called his father, then Riggs’s chairman. “I can’t take it anymore,” he said. “I quit.”

He figured he could live awhile on $9,000 he had saved. He also figured he could make good on a lifelong dream—learning to fly a plane.

From the time he was little, Allbritton had flown in his father’s jet. He remembers standing near the pilot and marveling at the dials and gauges. Finally, he spent two months at the Leesburg Airport getting his pilot’s license.

His father called every day at 6:30 am and asked: “How does it feel to be retired at age 22?”

Allbritton’s retirement lasted less than a year. In February 1993, his father put him to work in Allbritton Communications.

“They called it ‘TV 101,’ ” Robert says.

He spent two years learning the television business. He visited stations, sold ads, studied the technology, worked on programming. “I even did some on-air reporting,” he says.

His “professors” were Allbritton executives. Among them was Jerry Fritz, who is still with the company. Fred Ryan, who would become instrumental in growing Allbritton Communications and creating Politico, arrived in 1995.

“The company’s group head left, and I replaced him,” Allbritton says. It was 1996. He was 25.

In the next years, Allbritton Communications went on a buying binge. The company raised $200 million in the public debt market. It bought two stations and started one from scratch. Robert says he learned the most from buying two stations around Birmingham, Alabama, in 1996 and combining them into the strongest in the area.

“I interviewed the best anchors and on-air talent in the region and cherry-picked the best to create a star staff,” he says. “I learned that if you want to have a successful media property, it’s all about quality and personalities. You can’t skimp on that.”

His father expected him to work for a few years and return to school for an MBA. Robert sought advice from Stephen Trachtenberg, then president of George Washington University, which Robert had attended for a semester.

“Should I get an MBA?” Allbritton asked.

“If you want to take a vacation,” Trachtenberg said.

Joe Allbritton phoned his son a few weeks before Christmas 2000 and said, “I have six weeks to live.”

The senior Allbritton may have been overstating the case, but he had just been diagnosed with prostate cancer. He was in his seventies and in good health. Doctors at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York said he had a good chance for recovery.

The cancer treatment and recovery took Joe Allbritton away from his duties as chairman of Riggs Bank for more than a year. He asked his son to step in.

The day-to-day banking operations were being handled by veteran executives, but someone had to run the board. On Valentine’s Day 2001, Allbritton became chairman and CEO. He was two days shy of 32.

“The bank was bumping along. It had a good name. The systems were out of date. It needed more branches.”

Riggs had earned its good name. Founded in 1836, the bank had been called on to finance the Mexican War and the purchase of Alaska and to hold deposits for 21 Presidents.

In 1981, when Joe Allbritton bid $70 million for 40 percent of the stock and a controlling interest, Riggs was the region’s largest bank. By 2001, when his son took over, larger banks such as Wachovia and Bank of America had invaded, bought local franchises, and expanded branches and services. Joe Allbritton didn’t seem to want to compete with the megabanks; instead he created more of a boutique bank that served international customers and the diplomatic community.

“I had plans to bring the bank around,” Robert Allbritton says. “New systems, more branches, better hours.

“But,” he adds, “I never gave up my day job at Allbritton Communications.”

The terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon on September 11, 2001, focused attention on the international flow of money. Investigators reviewed Riggs’s diplomatic business and discovered loopholes and gaps in the way the bank monitored deposits.

Robert Allbritton would wake up for the next four years to stories about the investigations into the bank he now ran.

“It was a feeding frenzy,” he says. “Riggs was the meal.”

Federal regulators said Riggs had violated federal money-laundering laws. The bank agreed to pay a $25-million fine. The Justice Department and FBI looked into Riggs’s international-banking practices and charged it with “criminal failure to report numerous suspicious transactions.” Riggs pleaded guilty and agreed to pay another $16 million in fines.

Asked what he learned from being the focus of so much coverage, Allbritton throws up his hands and smiles.

“In retrospect, I look at articles about other people in a different light,” he says. “Any one article does not have all the facts.” Some journalists have “a natural tendency to want to prove their theory correct.”

Did he have any clue that Riggs might have been lax in monitoring foreign money transfers?

“These were things I didn’t ever know were there,” he says.

He takes a narrow view of the enforcement action: “At the end of the day, one person was lying, another was stealing—both were low-level people.”

At the height of the scandal, investigators turned their sights on Riggs board members and executives. None were charged. “I would assume after five years the investigations are over,” Allbritton says, “if we haven’t heard by now.”

Robert Allbritton believed he could keep Riggs in the family after the investigations. “I fully intended to resurrect it,” he says.

Federal prosecutors were harsh, but they also said, “We welcome the bank’s decision to accept responsibility, to implement internal processes to prevent future such violations, and to cooperate fully with our ongoing investigations.”

Throughout the investigations, Robert ran the bank well, according to Steve Trachtenberg, who was on the bank’s board. “He turned out to be a thoughtful, responsible, unflappable guy. He could not have been more mature if he had been 30 years older. He turns out to have a lot of steel.”

But he didn’t have the power to maintain Riggs as an independent bank. “The investigations forced our hand,” Allbritton says. In May 2005, Pennsylvania-based PNC bought Riggs.

“You hate to see an institution that was around for 150 years go away,” Allbritton says, “but it still lives on with new owners. They paid a decent price for it.”

Says Trachtenberg: “He saved everybody’s bacon. When Riggs sold to PNC, it was not what everyone dreamed of, but it was a plausible price.”

What the Allbrittons got from the Riggs sale is not public, but based on PNC’s valuation of the deal at around $650 million, the family could have come away with some $250 million.

At the same time Robert Allbritton was guiding Riggs through the money-laundering investigation and sale, he was courting his wife-to-be—and recovering from a broken neck.

He had met Elena Christine Hardy at Wesleyan, but they didn’t date. In 2000, she was practicing dermatology in Washington; he was in the banking and media business. Neither was attached. She and a few friends were planning a monthlong trip to Europe; she invited him to join them. He agreed.

The other friends bailed out, Allbritton recalls. He and Hardy decided to take the trip anyway. They stopped to visit with Allbritton’s parents, who were in Paris.

“If you can travel well with someone,” he says, “it’s a pretty good indication you can get along.”

Friendship grew into romance, which deepened when they returned to Washington. They got engaged and planned a wedding in the spring of 2003. Two weeks before the ceremony, Allbritton went skiing at the family vacation home in Snowmass. He’d been skiing since he was a kid, but he fell and broke a bone in his neck—and wound up wearing a collar brace at his wedding in May.

He was back on the slopes in a year.

Two years ago, the couple had a son, Alexander Lewis Allbritton. A few months before that, in January 2007, they paid around $28 million for a home on Q Street in Georgetown. The Federal-style estate has a main house with 12 bedrooms and sits on 1.6 acres. It was owned for many years by developer Herb Miller, who added indoor and outdoor pools, geothermal technology for heating and cooling, a spa, a gym, and a media room.

The final years of Riggs Bank were painful for the Allbrittons, but they also completed the succession from father to son. Riggs was in the past; Allbritton Communications was the future, and Robert was in charge.

Everyone—from Joe Allbritton on down—expected Robert to buy the nine New York Times Company television stations.

“I knew it wasn’t the right move for us,” he says.

He knew that managing nine more TV stations around the country would put pressure on his team of three executives. They had been running Allbritton Communications with him for a decade. They valued their time—their “mind share,” as he once put it. It gave them the ability and the agility to make decisions and move quickly. And at the moment, they were considering a venture in another news platform.

“The media world was a different place even three years ago,” Allbritton says. “We looked at radio, but WTOP was the best and not for sale. What else was out there?”

They decided to make a run at entering the newspaper market on Capitol Hill. A paper would be a nice fit with their broadcast and cable-news operations. Two papers—Roll Call and the Hill—were making money covering politics and policy.

Allbritton and Fred Ryan started negotiating with James Finkelstein, owner of the Hill. They made an offer, and Finkelstein seemed ready to accept. But the price kept going up and the deal never got done.

Ryan finally said to Allbritton: “We can start our own paper for less.”

Allbritton sought advice from Bob Barnett, a lawyer and literary agent for many top journalists. Barnett suggested that he hire Marty Tolchin to help launch the new enterprise. Tolchin, a Washington reporter with the New York Times for 40 years, had started the Hill and retired to write books. He agreed to help get the venture off the ground.

It was to be a newspaper in the image of the Hill. They came up with a name—Capital Leader—and began hiring reporters.

Says Fred Ryan: “It was going to be a more modest endeavor” than Politico turned out to be.

In October 2006, around the time he decided against buying the Times Company’s stations, Allbritton started focusing on the new newspaper taking shape on the first floor of the Rosslyn high-rise. It seemed like it was going to be a good paper.

“But it was not the level of quality I wanted to attach my name to,” he says. “I live here.”

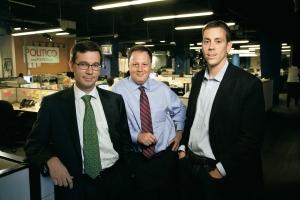

Across the Potomac, Washington Post political writer Jim VandeHei also was restless. “The news industry was changing,” he says. “We had no clue where it was heading.”

VandeHei was at the top of the reporting game. He had gone to the Post from the Wall Street Journal and become one of the paper’s top political writers. He had covered the 2004 presidential campaign and was free to roam the capital for stories.

“In some ways,” he says, “I couldn’t have been happier. I had one of the best one or two jobs in journalism. I loved Don—I loved Len.”

Don Graham is chairman of the Washington Post Company; Len Downie was executive editor of the Post.

“But,” says VandeHei, “I had an entrepreneurial streak.”

In the summer of 2006, VandeHei started talking about his doubts and dreams about journalism with John Harris, one of his editors at the Post. Harris had just returned to the paper after cowriting a book about the 2004 presidential campaign.

“I was getting bored with reporting,” Harris says. “I knew journalism was changing, and no one had come up with answers about how to take advantage of the changes.”

VandeHei, 38, and Harris, 45, don’t seem to be natural allies. VandeHei is tall and thin and has a manic bent; Harris is stout, a few years older, and seems more steady. VandeHei had been at the Washington Post since 2002; Harris had come to the paper right out of college in 1985 and risen through its ranks. He was a Post lifer.

“Jim and I started shooting the breeze,” Harris recalls. “They were ‘pass the bong’ conversations. Out of those conversations, we gropingly came to a set of ideas that led to Politico.”

The first idea was to hire a band of six star reporters and six younger reporters, launch a Web site, and start covering Washington politics in a new way.

“We both had the belief that Washington journalism was not living up to its reputation,” VandeHei says. “A lot of it was pedestrian, a myth. Could you create something on your own that would dominate the coverage of politics?

“All journalists are not created equal,” he says. “Give me the six best—reporters people must read.”

With an idea, no staff, and no money, VandeHei and Harris began talking with friends, who in turn set up meetings with venture capitalists. They met in the basements of homes in Northern Virginia about starting a company that would publish on the Web only.

“People liked the idea,” VandeHei says. “It became all-consuming for a few months.”

But when they started to add up the costs of starting such a venture, which would require about 48 employees, they arrived at $2 million. The moneymen backed off.

“Too much money, too much risk,” VandeHei told his wife.

“The air came out,” he says.

David Bass, a public-relations executive, had been hired to help Allbritton Communications find an editor for its new newspaper. He suggested that VandeHei contact Fred Ryan.

“I already talked to them,” VandeHei told Bass. Tolchin had discussed the Capital Leader editing job. He had said, “I don’t want to run a newspaper on Capitol Hill.”

Bass convinced VandeHei to meet with Ryan and Allbritton. They got together in the 27th floor. Allbritton talked up the Capital Leader.

“It doesn’t really work for me,” VandeHei said.

“Why?” Allbritton asked.

“You don’t have the right people to distinguish yourselves in a crowded market. You either do something big, concentrate on the Internet, or go home.”

“Tell me more,” Allbritton said.

VandeHei rolled out his vision of a band of top reporters who would dig for news and handle it in a different way.

“We would elbow our way to the front of the line in Washington reporting,” he said.

Allbritton liked what he heard. He asked to meet with Harris.

The next day, Ryan met VandeHei and Harris for lunch at the Metropolitan Club. They made their pitch again. A day later, they took Mike Allen to Rosslyn for a meeting. Both VandeHei and Harris had worked with Allen at the Post. He was covering the White House for Time. They considered him the best political reporter in town.

Allbritton was sold. There was one problem: VandeHei and Harris wanted to publish only on the Web.

At a meeting Allbritton said, “We have run the numbers. There’s not enough revenue online to make it work. You need a newspaper at least as a bridge, if not forever. The only way we can do it is to marry the two. If that works for you, we can do it.”

John Harris had reservations.

Are these guys on the level? he wondered. He considered himself a “citizen of the Washington Post.” Don Graham had had a hand in hiring him in 1985. Why not create their venture within the Post? They at least owed Graham a chance to hear their pitch.

On Wednesday, November 15, the week before Thanksgiving, they arranged a meeting in Graham’s office. In attendance were Graham, executive editor Len Downie, managing editor Phil Bennett, Web editor Liz Spayd, and Washingtonpost.com publisher Caroline Little. All except Graham have since retired or changed jobs.

“It was a bit like a state visit,” Harris recalls.

Graham ran the meeting. One of his first questions was “Why did you go to Allbritton?”

VandeHei and Harris chose not to answer the question directly. But they’d come to the conclusion that the Post under Downie wasn’t nimble enough to produce the Internet and newspaper publication they hoped to create.

VandeHei and Harris handed out a memo that described their vision. They talked for an hour about how they would hire a band of reporters to break news and dominate coverage. The Post brass took notes.

They seemed skeptical, especially of VandeHei. They pointed out that he had been only a reporter, had never edited anything, let alone run a news operation. Harris found himself defending his partner.

At one point, according to VandeHei, one of the Post executives said, “You are making a catastrophic mistake.”

That afternoon, Phil Bennett responded with the Post’s offer: Harris would stay in the newsroom as national political editor; VandeHei would go across the Potomac and become political editor at Washingtonpost.com. They could hire a staff of three. They would become the bridge between the Post’s newspaper and digital-news operations.

Harris was torn; VandeHei was ready to bolt.

It poured the next day. Jim VandeHei walked through the rain from the Post to the Jefferson Hotel for a lunch meeting with CBS News executive Paul Friedman.

Friedman discussed hiring VandeHei as an on-air reporter. VandeHei said he was “totally flattered” but was working on another venture. Friedman was curious. VandeHei described his vision for a political newsroom that would publish on the Web and in print.

“Brilliant,” Friedman said.

VandeHei said Harris was concerned they would lack exposure and lose their standing as top political reporters.

“What if I got you on Face the Nation every other week?” Friedman asked.

VandeHei says it was the “holy s—” moment.

Friedman called CBS News president Sean McManus to make sure he could make good on the promise; VandeHei called Harris at the Post.

“I think we have a deal clincher,” he said. “Come over to the Jefferson.”

Harris grabbed an umbrella and walked over. The three talked. McManus was on board. VandeHei called Fred Ryan and asked if he and Allbritton could come talk with Friedman. The two executives took a cab across the river and met with Friedman. There were handshakes all around.

Walking through the rain back to the Post, VandeHei said to Harris: “Dude, this is meant to be. We’re doing this.”

Harris still had doubts.

That Saturday, he asked VandeHei to meet him for what they now call “the coffee walk.” Driving to Harris’s house in Alexandria, VandeHei practiced his pitch.

They walked and talked. Harris spelled out his reservations and argued for staying with the Post. He feared they would wind up playing on computers in their basement in a version of Wayne’s World. He said they risked losing their high-profile appearances on TV talk shows; they would drop into oblivion.

“You’re probably right,” VandeHei said.

He arrived home with a long face.

“Harris changed your mind, didn’t he?” said his wife, Autumn, a social worker and former Capitol Hill staffer. Then she said, “That’s not going to happen.”

She started whipping off e-mails to Harris, invoked Winston Churchill and Teddy Roosevelt, and said the Allbritton offer was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

Harris and his wife, Ann O’Hanlon, read the notes and reconsidered. Ann was with Autumn and Jim.

“Okay,” Harris said. “Let’s do it.”

That Sunday, November 19, VandeHei called Ryan, who was hunting pheasant in Boonsboro, Maryland. VandeHei, a native of Wisconsin, was watching a Green Bay Packers game. “I want to get this done before the end of the game,” VandeHei said. “We want to do this.”

“Okay,” Ryan said. “John will be editor-in-chief, you will be executive editor. We’re off to the races.”

The defection of VandeHei and Harris jolted the Washington Post. The paper was already reeling from losses in circulation and advertising revenue. Too many top reporters had left for other news organizations or taken buyouts. In the view of many journalists, the loss of two more top political writers threatened the paper’s franchise on political reporting.

“I don’t see us competing against the Post,” Robert Allbritton tells me. “We’re competing against everyone out there. One guy battling another is old-media thinking. True, our first two guys came from the Post, but most came from all over the place.”

Mike Allen came from Time, Roger Simon from Bloomberg News, Ben Smith from the New York Daily News. David Rogers came from the Wall Street Journal. Danielle Jones came from the Hotline. Eamon Javers came from Business Week. The only other hire from the Post was Kim Kingsley to run public relations.

When Harris and VandeHei announced they were leaving for Politico, Don Graham sent Allbritton a note wishing him luck.

“I love Don,” Robert says. “I absolutely admire what he’s been able to do with himself and his life.

“We’re both very fortunate people,” he says. “We’ve had opportunities most people can only dream of. Don grabbed those opportunities and did something with them. He’s engaged in the community and journalism beyond the Post. I know he has a commitment to a high level of quality.”

Mike Allen, Politico’s chief White House correspondent, rocked the Post’s reputation for journalistic ethics with a story in July about the paper’s plan to bring reporters, editors, politicians, and lobbyists together in a “salon”—paid for by corporate sponsors—at publisher Katharine Weymouth’s home. Politico got mileage from the scoop; the Post endured days of negative press.

Allbritton and Weymouth are about the same age and represent the next generation of media magnates. Allbritton says he wrote Don Graham shortly after Weymouth took over in February 2007 and asked to meet her. Graham set up a lunch at the Hay-Adams hotel.

“She struck me as very bright and intelligent,” Allbritton says. “She was very aware of the challenges the newspaper industry is going through.”

Weymouth and Post executives wanted to use the salons to help meet the financial challenges. Allbritton chose a different course: He arranged public debates and forums, paid for by Politico, to promote Politico’s brand.

Meanwhile, the political reporting at Politico often eclipses the Post’s coverage—from the White House to Capitol Hill.

“It’s hard to compare,” Allbritton says. “They’re publishing 600,000 copies; we’re putting out 35,000. We’re not trying to be all things to all types of people; we’re trying to do one thing well.”

And fast. And furious.

Jim VandeHei often arrives at the Politico newsroom in Rosslyn around 6 am to push his troops to “win the morning,” as he exhorted in a memo.

Mike Allen arises at 4 am to write the Playbook, his daily take on news, links to articles, musings on the coming day, and birthday greetings.

Media writer Mike Calderone was riding the 42 bus down Connecticut Avenue when he got e-mails that Joe Scarborough had dropped the “F-bomb” on MSNBC. He jumped off at Dupont Circle, plugged his air card into his laptop, and filed for the Web site.

“We wake up to our BlackBerrys, start filing, and keep it up all day,” says a reporter.

Allbritton positioned the Politico newsroom at one end of an open room the size of a football field on the first floor of 1100 Wilson Boulevard. WJLA-TV and NewsChannel 8 news operations have been squeezed back to make room for around 75 Politico reporters and editors.

Politico publishes a free newspaper Monday through Friday when Congress is in session; 32,000 copies are distributed to congressional offices, the White House, executive departments, and boxes in downtown DC. But most readers get their news from Politico’s Web site.

“For me, Politico is pure digital,” says Staci Kramer, who lives in St. Louis and covers the media for the Web site paidContent.org. “You have to flip your view and think of Politico beyond what you see in DC. For most readers, it’s not a newspaper.”

VandeHei and Harris often talk about Politico’s digital platforms and the newsroom’s “shared DNA and metabolism.”

What gives Politico a leg up on the Post and other newspapers is that it started as a Web publication with a print edition rather than a print product that publishes on the Web. Other than that, Politico follows an old-school model of gathering and disseminating news.

VandeHei and Harris hired experienced reporters, directed them to flood the zone, and expect them to work hard and file several times a day. In the old days, reporters would cover a crime scene, phone the paper, and say, “Rosie, give me rewrite.” Now reporters type the stories and send them over the Internet, but the essential reporting remains the same.

“They have done a very good job of establishing themselves as one of the go-to sites for Washington political coverage,” says Brian Kelly, editor of U.S. News. “One glance at their Web site and I get a sense of what’s going on.”

In Politico’s early days, Harris was forced to apologize in print for an inaccurate article or two. The reporting sometimes seemed breathless and skimpy during the 2007 presidential campaign. But it has matured.

“They have done an impressive job of changing from sizzle to substance,” says the editor of a rival publication.

Politico’s PR staff makes sure scoops show up on other Web sites and reporters get time on cable TV. Tune in to a political discussion on TV or radio and you’re likely to hear a mention of Politico or see one of its reporters; in less than three years, it has built a brand that rivals the Washington Post in political news.

But pushing reporters and muscling into the media market has come at a cost.

“The burnout factor is high,” says one Politico writer. “They haven’t figured out a way to fix it or avoid it.”

Ryan Grim started reporting for Politico when it launched in 2007; he had come from the Washington City Paper. “The congressional team excelled in covering the bailout story,” he says. “We worked and filed midnights on Saturday because that’s when Henry Paulson was meeting and making decisions. But that pace of coverage never stopped.”

Grim left Politico in January to cover Congress for the Huffington Post. “It’s wrong what they do to people,” says Grim, 31. “Political reporting means long and unpredictable hours, and that’s fine. But making weekends mandatory when nothing’s breaking isn’t sustainable.”

Grim says that the newsroom in Rosslyn where editors and Robert Allbritton work is “extremely friendly” and that they don’t require the extreme hours of everyone—but almost everyone. The White House staff, for instance, works a two-day shift every other weekend, and several congressional reporters have worked seven-day weeks with little downtime since September.

What’s different about working for the Huffington Post?

“I can go home,” he says.

Last December, after Barack Obama’s victory but before his inauguration, Harris met with Allbritton in the newsroom to map out their plan to cover the White House. They wanted to hire some name-brand reporters who had sources and firepower.

“Here’s a list of six,” Harris said. “We would like to hire two.”

Most Washington editors and reporters are skeptical about claims that Politico is turning a profit, in part because Allbritton has hired so many high-priced journalists. Reports of wages in the $200,000 range are fiction, VandeHei says. “Our salaries are competitive with the New York Times but not way above.”

Allbritton took the memo up to the 27th floor. He pondered the choices, did some research, conferred with his executives. Two hours later, he took the elevator back down. “We ought to hire them all,” he told Harris and VandeHei.

“Are you serious?” Harris said.

“It’s time to double down and take another risk,” he said.

Politico hired Josh Gerstein from the New York Sun and David Cloud from the New York Times. It made runs at four others. Cloud became Politico’s chief national-security writer but lasted only six months. Turned off by Politico’s manic pace and narrow focus on politics, he quit in June.

I asked Allbritton how he could have started up a news operation and be making money when so many newspapers and Web sites are operating in the red?

“We exist on Planet Capitol Hill,” he says. “It is its own little microcosm. The defense contractors, the advocacy groups, the nonprofits have to get their messages out, and they have good-sized budgets.”

And they have been advertising in Politico’s print and Web editions. Boeing airplanes have flown across Politico’s home page. There are days when half of the print edition’s 44 pages are ads for companies such as Goldman Sachs. There are also days when only six of 28 pages are paid ads.

The advertising-rich media market on Capitol Hill already supports the Hill, Roll Call, National Journal, and Congressional Quarterly. It’s not far-fetched to see another publication or two feeding happily at the same trough.

Staci Kramer of paidContent, which covers the publishing business, has written often about Politico. “They have a hybrid model that relies on both print and digital,” she says. “If they relied on one alone, it would not work. They have multi-revenue streams and a layered audience, so they can take advantage of their national reach and a very targeted local readership at the same time.”

She agrees that ad dollars are plentiful on Capitol Hill. “These publications can make a lot of money from a small group of advertisers,” she says. “But at the bottom of it all, when you can’t see someone’s books, you have to rely on what they say.”

Allbritton says, “We’re making a little bit of money in the middle of a recession, and we’ve been in business only 2½ years. The pie will grow.”

Moody’s Investment Service, which rates and analyzes global businesses, wonders if Allbritton Communications is making enough money to service its debt. In its February 11 report, Moody’s says Allbritton has annual revenue of approximately $225 million, but it downgraded the company’s outlook to “negative.”

“Allbritton derives the majority of its revenue from advertising,” the report says, “which faces cyclical pressures and heightened price and volume competition from media fragmentation. We anticipate considerable revenue pressure in 2009 due to weak consumer spending and credit market conditions, as well as the normal odd-year decline in political advertising, and forecast that Allbritton revenue will decline by 10% to 15% for calendar 2009.”

On January 23, Robert Allbritton called WJLA staffers to a meeting. He described the difficult financial situation and announced that he would have to lay off 26 staffers. It was the first major cutback the station has had to make. Many veterans, such as Andrea McCarren, found themselves out on the street. The Washington City Paper called it a “bloodbath.” He assured the remaining employees that their jobs were secure, but newsroom directors told them that afternoon they would have to accept a pay cut and a subsequent salary freeze.

“We’re done cutting,” Allbritton tells me.

Moody’s analyst Karen Berckmann, who wrote the reports on Allbritton, explains that the company’s negative rating is due to the balance of debt to earnings it must maintain to meet covenants with its lenders.

“They could generate more than enough cash to pay their interest expenses,” Berckmann says. “In the past, they have given a lot of cash to the owners. It’s been a drag on the company’s cash flow. They are not likely to continue distributing cash to the parent company.”

In other words, the Allbritton family might have to take less profit for a time.

Compared with his company’s eight TV stations, Politico is a relatively small part of Allbritton’s costs and revenues. Moody’s called “the achievement of profitability for Politico also a positive for the rating.”

Allbritton dismisses the negative rating—he says his company is in great shape and won’t miss one bond payment.

“We have no problems,” he says.

Every Friday, Allbritton meets with news directors at WJLA and NewsChannel 8; then he gets together with Harris and VandeHei, as he does most mornings.

“I’m a pretty involved guy,” he says.

Allbritton’s involvement with Politico steers clear of the publication’s political tone. It has no opinion page. VandeHei and Harris say that neither Allbritton nor Fred Ryan has ever weighed in on coverage. Ryan worked in the Reagan White House and served as Ronald Reagan’s chief of staff when the President left office; he’s still close with Nancy Reagan.

“I check my political views at the door,” says Ryan. “We would not get quality journalism if we were pushing the coverage left or right.”

I catch up with Allbritton in the glassed-in conference room in the center of the combined newsrooms. He can see all of Politico and the assignment desk of the TV stations.

I ask if he sees himself as a pillar of the Washington community or a businessman who lives here. He chooses the latter.

“I do have a sense of responsibility for this community,” he says. “My father’s theory was that certain folks will know about what kind of good works he did. I tend to agree with that.”

The Allbrittons have been very philanthropic. Robert and Elena pledged $5 million to create a Center for the Study of Public Life at Wesleyan. “I am a huge supporter of education,” he says.

Most of the family’s gifts are anonymous. Public records show that the Allbritton Foundation, based in Texas, has focused its donations on cancer research, universities, and hospitals, but it has also donated funds to the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies and the Capital Area Food Bank. Robert meets with his parents every spring to designate recipients. Don’t expect any press releases.

“I see myself as a normal kind of person,” he says. “I like driving myself to work, shopping for my own groceries. I don’t want to lose touch with what people are going through. For many people in DC, the most important thing is what they project, how they dress, which party they were invited to. That’s never been important to me.

“I’m a pretty happy guy. I wake up every morning and say, ‘Thank you, God, for a wonderful day.’ ”

His peace of mind comes in part from his decision not to buy the nine New York Times Company TV stations three years ago.

“I knew I wasn’t going to sleep well with that much debt on the books,” he says.

Perhaps that’s the secret to his success: eight hours a night—except when son Alex wakes him at 6.

This article first appeared in the August 2009 issue of The Washingtonian. For more articles from that issue, click here.