Fairfax County police officer knocked on Lanashia Wells’s car window around 8 in the evening. Wells had been sitting in the parking lot at Landmark Plaza for more than seven hours. Waiting. She’d left only a few times—once to let police into Kamron’s bedroom so the dogs would have his scent, another time to check under parked cars, trying to find him.

“Ma’am,” she remembers the officer saying. “I have something to show you.”

Wells didn’t want to see what was in his hand—she was sure it was a photo of her five-year-old son lying in a ditch. Nobody had seen the boy since he’d wandered away from his grandfather at the grocery store that morning.

“No, thank you,” she said, rolling up her window. What do you mean something to show me? she thought. I’m not looking at that.

The officer knocked again. “It’s okay,” he said. “I just want to show you a picture.”

The blurry photo—taken from a security camera near Rita’s Water Ice, across the parking lot from the Shoppers Food Warehouse—showed a woman wearing high-heeled boots and smoking a cigarette, holding a small boy’s hand.

“That’s my son,” Wells said.

“Are you sure?” the officer asked. The photo had been taken from behind, so she couldn’t see the boy’s face.

“I just know,” she said. “That’s my son.”

Fairfax County police get a call about a missing child nearly every day. Most reports are resolved quickly: A small child wanders away to look at something. A parent finds her daughter at a friend’s house. A teenage runaway comes home.

A few hours into the search for Kamron Wells on Sunday, October 19, 2008, police had a feeling they were dealing with something different. The kindergartner wasn’t hiding from his grandpa or running around the shopping mall. He was gone.

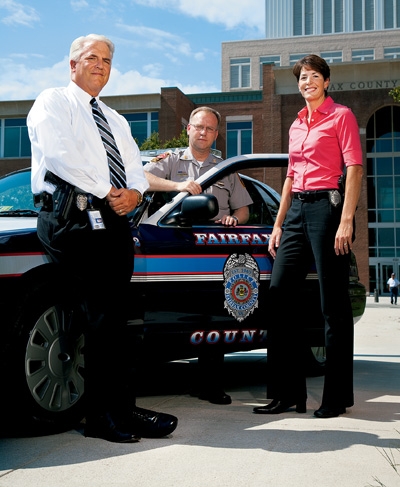

“I think about Adam Walsh,” says police captain Purvis Dawson, a father of three who supervised the search. “I think about Melissa Brannen, who was abducted down in Lorton—that happened within a couple miles from my house when she went missing from a Christmas party.”

Strangers rarely snatch children. Of more than 12,700 cases the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC) helped investigate last year, the majority were runaways, lost children, and kids who’d been abducted by a family member. About 150 involved a perpetrator who wasn’t related to the child but had some connection. A small number of those were stranger kidnappings.

In 1981, when Adam Walsh vanished from a Sears store in Florida, most law-enforcement agencies waited at least 24 hours to get involved in a missing-child case. “It was standard practice,” says NCMEC president Ernie Allen. “Police would say, ‘Your kid probably just ran away—if he doesn’t show up in a day or two, call me back.” Missing children weren’t entered into the FBI’s national crime system.

“Mom and her six-year-old son are at a shopping mall and the little boy disappears,” Allen says. “Two weeks into the investigation, the Walshes—who’d created their own posters, circulated Adam’s picture, mobilized friends and family, and called every police department in their state—discovered that 80 percent of the police in Florida had no idea who Adam Walsh was.”

When Walsh was kidnapped and murdered, there also was no such thing as an Amber Alert, the broadcast emergency-response program that has aided in the safe recovery of more than 500 missing children. The alert is named for a nine-year-old Texas girl, Amber Hagerman, who was abducted in 1996 while riding her bicycle and was found dead four days later. Someone called a Dallas radio station after the murder and suggested that police activate an early-warning system for missing children, the same way meteorologists do for severe weather. The missing-children center has a recording of the 911 call from the first successful recovery: A man in Texas heard an Amber Alert on the radio in 1998 and saw the vehicle in question driving in front of him. Inside was a two-month-old girl who’d been taken by a babysitter.

The search for Kamron Wells started as soon as the 911 call came in at 11:48 am. By noon, the county’s helicopter was in the air. Captain Dawson called in a bloodhound.

“When children are abducted and murdered,” Allen says, “in three-quarters of the cases the child is dead within the first three hours.”

Lanashia Wells’s father, Charles Williams, thought his grandson was next to him in the frozen-food aisle. He was watching Kamron and his older sister, Tylah, while Wells, a general-surgery resident at Howard University Hospital, was at work. Williams had moved in with his daughter earlier that year to help with the kids—take them to the school-bus stop, make dinner, give them baths. He’d gone to the store with them that Sunday because he wanted to bake a pie.

The frozen pie crusts weren’t where Williams thought they’d be, so he asked someone for help. Two aisles over, a store employee told him.

“Come on, Kamron,” he said. “Stay behind Pa-Pa.”

When he got to aisle 10, he opened one freezer door, closed it, and checked another. He turned around and the little boy wasn’t there.

“Kamron?” Williams yelled. His grandson was easily distracted.

“Kamron? Where are you, Kamron?”

Tylah came back from getting a cart and asked where her brother was. “I don’t know,” Williams said. “He was just here a second ago.”

They went up and down every aisle and asked the manager to make an announcement: “If your name is Kamron Wells, please come to the front office now.”

Forty minutes passed. Williams didn’t have a cell phone. “You need to call the police,” he told an employee.

Kamron’s mother was seeing patients at Howard University Hospital when her pager went off.

“Dr. Wells,” an operator said. “We have a call for you.”

Wells had trusted her father to help care for Kamron and Tylah for nearly eight months. As a first-year resident, she often worked 80-hour weeks and occasionally stayed at the hospital. She was usually home in time to check the kids’ homework and make sure they’d brushed and flossed. Kamron liked to lie in bed with his mom and practice reading three-letter words. Sometimes she fell asleep before he did.

When her dad called and said, “I can’t find Kamron,” Wells assumed her son was messing around. “You better find him,” she said.

Kamron was an active kid—he played outside every day after school and enjoyed karate. He liked tickling her and having thumb wars. She called him “a little knucklehead.”

She’d shopped with Kamron enough to know that sometimes he lagged behind in the aisles. She didn’t make him stand by her side every second.

Wells went back to the hospital’s intensive-care unit, expecting her dad to call right back. Instead she got a call from the Fairfax County police.

“We’re looking for him,” an officer said. “We’re doing everything we can.”

Captain Dawson lost his four-year-old daughter in Springfield Mall about ten years ago. The little girl had a habit of holding onto his back pocket when they were out together, and when he went to take his wallet out to pay for something, he realized that her hand wasn’t there.

What am I going to tell my wife? he thought. The mall was packed with holiday shoppers. He grabbed a security guard and told him he was an off-duty police officer and his daughter was missing. They locked down the mall and found her 15 minutes later in a toy store.

When Dawson pulled into Landmark Plaza, just off I-395, he overheard Kamron’s grandfather calling himself a failure. He’d felt the same guilt.

“We’ve checked the shopping center,” a patrol officer told him. Shoppers Food Warehouse kept customers inside while police went through bathrooms, storage areas, and cardboard boxes. “The child’s nowhere to be found.”

Dawson broke the 18-square-mile Mason Police District into grids and sent ground officers to nearby homes and apartments. He issued a flash bulletin to law enforcement in DC, Maryland, and Virginia, including bus and airport security, and stationed officers on the roof of the grocery store. The Alexandria City police, who assisted with the search, put out a “reverse 911” call, a computerized phone message that went to every house in the west end of Alexandria.

By early afternoon, every available Fairfax County police officer was looking for Kamron. They asked store employees in and around the grocery store for access to security cameras but ran into problems. One store didn’t have a working camera; others were staffed by part-timers who didn’t know where they were or how to work them.

Dawson kept track of everyone’s whereabouts on a dry-erase board. He had some officers running through parks and wooded trails, others riding dirt bikes into creek beds and pulling covers off community pools.

Kamron’s mother was standing by a patient’s hospital bed, an hour after the police officer called, when she realized she had to leave. She’d gone back to work as if the call had never come.

What is wrong with you? she thought.

She pulled into the Shoppers parking lot around 1 pm and saw police cars everywhere.

They’ll find him, she told herself.

She thought maybe Kamron had wandered into the barbershop where he got his hair cut or walked home to see a friend in their Lincolnia apartment complex. She worked so much that aside from dinner at Red Lobster or occasional trips to Chuck E. Cheese’s, she didn’t get to take him out very often. She couldn’t imagine where else he could have gone.

Six hundred feet in the air, Fairfax County Bell 407 helicopter pilot Charles Angle and two flight officers were on the lookout for a boy in a gray hooded sweatshirt and blue jeans. In daylight searches, a flight crew can tell just by looking out the window if someone on the ground is wearing stripes or solids or carrying a backpack. With a special camera, they can read car inspection stickers.

Angle flew over playgrounds and radioed ground officers if he saw a child fitting Kamron’s description. He was 45 minutes into his search, flying in a left-hand orbit over the interstate, when he got a call from the Washington Flight Tower saying he had to suspend his flight because Marine One was going up. Even police helicopters have to clear the airspace around Washington when the President travels.

“Let me know as soon as I can get back in there,” Angle said. “We’re working a possible kidnapping.”

He’d just turned around when the flight tower radioed.

“Return to your search area,” a man said. It was the first time Angle had heard of the Secret Service making an exception. “Marine One has cleared you.”

Most missing-child cases don’t meet the criteria for an Amber Alert. The Amber Alert program usually requires a vehicle description or information about the suspected abductor. More than 2,000 kids are reported missing every day nationwide: If state police put out too many alerts with too little information, police say, people will stop paying attention. Last year, Virginia issued only two.

For a while, Dawson told himself Kamron was lost. But the first three hours, the ones that counted most, passed without a sighting. He’d handed out fliers with the boy’s picture on them and asked store employees with copy machines to keep making more. Kamron had lost his two front teeth since the picture was taken, but it was all they had. He handed them to reporters and said, “Put this on the news.”

He’d been a cop for 27 years, long enough to know that every now and then a child didn’t come back and that not all abductors were scary-looking men in white vans. He still remembered the video of Melissa Brannen in her Christmas dress—she’d disappeared while her mother stood nearby. A ten-year-old named Rosie Gordon had been kidnapped from her Lake Braddock neighborhood in 1989 and found dead days later.

“Find me more bloodhounds,” he said.

One was already out hunting for Kamron. Bloodhounds can track a human scent for up to five days. The police department’s other search dogs are German shepherds, used most often to find drugs and to look for criminals. Dawson preferred bloodhounds because if a shepherd spotted Kamron, the dog might try to chase him down.

An officer accompanied Lanashia Wells back to her apartment to get something for the bloodhounds to sniff. She came back with her son’s toothbrush.

Kamron’s grandfather walked back to the apartment with Tylah. He’d lived in Los Angeles for most of his grandson’s life and was just getting to know him. He liked taking him to buy his favorite candies, Blow Pops and Now and Laters, and watching him play with his sister. Tylah looked out for Kamron, often trying to get him out of “time-out.”

His daughter was so angry that she had barely spoken to her father since he’d called to tell her what happened.

He couldn’t stop thinking: They’re going to kill my grandson. “Please don’t let nothing happen to him,” he prayed.

Wells didn’t want to talk to anyone. She parked far away from the news trucks, locked her doors, and turned on rhythm and blues. She flashed her car lights so a cousin who’d come to help look for Kamron could find her in the parking lot.

She sent text messages to relatives but didn’t pick up when they called.

She’d spent time as an operating-room technician in the Army. At work, she treated people with gunshot wounds to the head. Patients went into cardiac arrest while she was in charge, and they didn’t always make it. “Time of death is . . .” she’d say.

Even though this was different and the victim was her son, whatever it was that kept her from falling apart then was helping to keep her from falling apart now: This is not the time to get emotional.

She’d broken down crying at a day spa once when her daughter got acetone in a cut and screamed in pain. Now she had no idea where her little boy was—nobody did—and she was just sitting there.

At four in the afternoon, Captain Dawson called in the county’s Child Exploitation Unit, which handles missing juveniles. It was protocol to bring them in when patrol had exhausted its resources. The helicopter had refueled three times; officers had knocked on thousands of doors.

Detective Jeannette Wagner wasn’t used to seeing a mother so calm. She thought it was strange that Wells wasn’t asking for updates.

She brought Kamron’s mom into an abandoned building next to Shoppers so reporters wouldn’t spot her. “What are the visitation arrangements?” she asked. “Do you have a boyfriend?”

Wagner called Kamron’s father, Marcel Wells, who was out searching on foot, and asked him to come talk with her. She learned that Lanashia and Marcel shared custody of Kamron and Tylah—they’d met in the military and had separated after several years of marriage—and the split appeared to be amicable.

Marcel Wells worked two jobs and saw the kids when he could. If they were sleeping when he picked them up from a visit with their cousin, he’d carry one over each shoulder. Kamron adored him.

Wagner’s partner, Bruce Wiley, was home getting ready for a Redskins–Browns game when she called him. Most of Wiley’s cases are runaways, solved quickly. When she told him Kamron hadn’t been seen in six hours, he called a friend and colleague, special agent Bill Kim, at the FBI’s Washington Field Office.

“How many people do you need?” Kim asked.

“How many have you got?” he said.

Wiley asked colleagues to pull up the sex-offender registry: “I need to identify every sex offender within four to five miles.”

Wiley couldn’t understand how a five-year-old boy could be alone that long without anybody seeing him and calling police.

He’s with somebody, Wiley thought. Someone’s got him, and he’s blending in.

Late in the day, a bloodhound tracked toward a wooded area along 395, south of Little River Turnpike. The dog’s handler radioed pilot Charles Angle and asked him to check it out. The helicopter was equipped with an infrared camera that detected heat sources from the air. If the flight crew picked up something suspicious, they could direct the dog handler to that spot. But the search came up empty.

FBI special agent Bill Kim and his team had little to go on when they arrived. There were no leads. The county police brought in meals and set up shelters for officers staying overnight. Intelligence analyst Heather Gordon, who works with Kim on the Washington Field Office’s Child Exploitation Task Force, tried not to let her mind go to dark places. She’d handled child-exploitation cases and knew that enough time had passed for anything to happen.

Kamron’s mother knew it, too. After the sun went down, she turned around and looked in her back seat, where she was used to seeing Kamron and Tylah goofing off.

There’s a possibility that I could look back here and see only one child, she thought. She got out and started walking around the parking lot, peeking into car windows.

Kim decided to start over on the search. He paired agents with Fairfax County officers and sent them to apartments, hotels, and shops they’d already checked. He called in store managers on their day off, hoping to track down surveillance photos. The circumstances had changed: Employees who’d told patrol officers early in the day that they didn’t have access to footage might have realized that this wasn’t a boy who’d been separated from his family—this was a missing child.

Around early evening, a surveillance photo came in from the BB&T bank. Then the FBI got pictures from Rita’s Water Ice and from Ross department store. Investigators saw a woman in jeans and high-heeled boots smoking a cigarette. In other shots, they saw the same woman walking with a small boy. That’s when an officer knocked on Lanashia Wells’s car window to see if the boy was Kamron and if the woman was a stranger.

Detective Wiley had made his first call to Virginia State Police on his way to the scene. It was his first time requesting an Amber Alert.

“This is a five-year-old kid,” he said. Temperatures were supposed to dip into the 30s overnight. “We need to get something out and we need to get it out now.”

A sergeant at the Missing Children’s Clearinghouse said he would issue an “endangered alert” and asked Wiley to call back when he had a photo and more information. Endangered alerts go out to local media—news outlets such as CNN occasionally pick them up—while Amber Alerts interrupt television and radio programming. Some abductors have released their victims after seeing their own license-plate number on a highway sign.

Investigators called back when they’d obtained the surveillance photo, and police agreed to issue an Amber Alert at 8:45 pm. A Sunday-night football game was on.

The message read: THE FAIRFAX COUNTY POLICE DEPARTMENT IS LOOKING FOR KAMRON DEVEAUX WELLS, A BLACK MALE, AGE 5 YEARS OLD, HEIGHT 3 FEET, WITH A THIN BUILD, WITH BROWN EYES AND CLOSE SHAVED BLACK HAIR. THE CHILD IS BELIEVED TO BE IN DANGER.

The missing children’s center, located in Alexandria, handles secondary Amber activations. It sent out wireless notifications via text message and e-mail, and the alert spread through Internet service providers, instant messages, Yahoo, Google, MySpace. More than 100 highway trucking companies got the alert, as did digital signs run by the Outdoor Advertising Association of America, which could flash it to drivers. Kamron’s picture was all over the 11 o’clock news.

The phone started ringing moments after the Amber Alert. A call came in around 10 pm from a Metrobus driver who’d seen Kamron’s picture on television. She told police that she remembered seeing a black woman in high heels running to catch the bus—and that she’d stopped for the woman because there was a child with her.

“Kamron, come on—get on the bus,” she’d heard the woman say.

“How sure are you she said the name Kamron?” a detective asked.

The driver said she knew it was them because the boy’s name stuck out in her mind at the time. She dropped the two of them off outside an Alexandria apartment building just after noon, she said, but noticed they didn’t go in.

Investigators expanded their search to restaurants and hotels they hadn’t canvassed before. They picked up cigarette butts from outside Rita’s Water Ice in case they needed DNA. Calls were coming in from as far away as Harrisonburg, Virginia, where a woman claimed to have seen the boy with a white female who had graying hair.

Wiley started thinking about getting officers rested for the next day. He was relieved to have surveillance pictures, but they were ten hours old. If something bad was going to happen to Kamron, it probably already had.

It was after 1 in the morning on Monday, October 20, when DC police lieutenant James Cullen, on routine patrol in Northwest DC, just south of Walter Reed Army Medical Center, saw someone trying to flag him down. The man, driving an SUV in the opposite direction, had slammed on his brakes.

“One block. Right there. The Amber Alert!” the man said through the open car window.

He directed Cullen to the corner, where the officer saw another male waving at him and a female pacing. They seemed to be arguing.

“There was an Amber Alert in Virginia on TV,” that man told Cullen. “This is the lady that took him. I’ve got the kid in my house.”

Cullen usually slept through the late-night news when he worked midnights and hadn’t heard about a missing child in Virginia. In 28 years as a DC cop, he’d never been involved with a kidnapping case.

“What’s going on here?” he asked the woman.

“That’s my boyfriend,” she said. “He’s just mad. He’s drunk.”

The man, Michael Cook, told Cullen she wasn’t his girlfriend—the two had met earlier that day—and that she’d kidnapped a child from Virginia.

Another officer arrived and detained the woman while Cullen followed Cook to a rowhouse at the corner of Ninth and Hamilton streets.

Someone came to the front door and told Cullen that the child was in the basement. “Come on,” he said. “I’ll show you.”

The furniture was tattered, and the house reeked of marijuana. Cullen walked down a set of creaky stairs and saw a little boy on a dirty mattress, sound asleep.

The boy barely roused when Cullen picked him up, put him over his shoulder, and carried him outside. His voice was quivering when he awoke in the back seat of a police cruiser.

“Daddy?” he said, then started to cry.

“We’re police officers,” Cullen told him. “You’re okay now. We’re going to take you home.”

He asked the boy his name.

“Kamron.”

Cook told Cullen he’d met the woman, Falah Joe, on a Metrobus and they’d arranged to have a sexual encounter at the house of his friend Milton Mooya while Mooya cared for the child. He said the woman told both men Kamron was her son, but at one point the boy said, “That’s not my mommy.”

Investigators say Mooya had been watching football earlier that night when an Amber Alert flashed across the screen. He realized that the boy in his house looked like the one he’d seen on television. When Mooya went to call police, Falah Joe ran from the house and Cook chased her outside.

Cullen let Kamron play computer games in a police cruiser while he waited for the DC police youth division to arrive to take the child back to Fairfax. He’d been gone nearly 14 hours.

Detective Wagner wanted to let Kamron’s mom and dad see him, but she had to talk to him before anyone else did.

Kamron was smiling when he got out of the police car. Wagner picked him up, and he put his arms around her neck. “You gotta come with me,” she said. She had a small son of her own—from then on she knew she’d be holding onto him more tightly.

Wagner took Kamron into the command bus, where he told her his Pa-Pa had left him at the store and this “lady” said he could go home with her but would have to spend the night. He said some of the clothes he was wearing weren’t his—and that the lady told him he looked like her son, which Wagner later found to be true.

At times Kamron made sense; at times she could tell he was creating things in his mind. He seemed excited that he’d gotten to be in a bus, and then another bus, as if the whole day had been a big adventure.

His mom was brought in a half hour later. She sat down, and Kamron gave her a hug. “Mommy,” he said. “I missed you.”

When Captain Purvis Dawson awoke the next morning, his wife had already watched the news. He’d been sent home before the Amber Alert because he’d worked too many hours.

“They found that little boy last night,” she said.

Bill Kim, Heather Gordon, and other members of the task force spent the next 48 hours retracing Falah Joe’s steps. She was charged with interstate child abduction, a federal crime with a mandatory minimum of 20 years, which meant the FBI would assist the US Attorney’s office in building its case.

It wasn’t her first arrest. She’d served time in prison for assaulting a deputy marshal with scissors in DC Superior Court during the sentencing of an ex-boyfriend. She’d been trying to stab her ex, who was convicted of murdering someone in the club where Joe had worked, when the marshal intervened.

A former stripper, Joe told a psychiatrist she’d gone to get her hair and nails done in Landmark Plaza and saw Kamron alone outside Rita’s. She had a young son of her own, whom she’d lost custody of, and thought Kamron looked like him. She called the chance meeting “a gift from God.”

She said she took Kamron’s hand and walked him to the other side of the strip mall, passing BB&T—where she was caught on a surveillance camera—and the two got on a Metrobus. They ended up at her mother and stepfather’s house, about three miles from Shoppers Food Warehouse, where she took off her jacket and boots, changed Kamron into some of her son’s clothes, and gave him a Spider-Man backpack.

Joe’s stepfather told investigators he was outside fixing his car when he was saw his stepdaughter walking toward the house with a child. She was allowed to stay with her mother and stepfather but didn’t have a key to the house. Joe told her stepfather that Kamron was her boyfriend’s son, and he didn’t ask questions. She was a grown woman out on a Sunday, and he was busy with his car.

For most of the afternoon, Joe went back and forth between her mother’s house and a community center across the street, where homeless people were allowed to sleep and where her boyfriend often stayed. She told people there that Kamron was her nephew. She got him lunch from McDonald’s and brought him to a 7-Eleven, where employees remembered her high boots with tassels. Investigators don’t know where she was headed or what she planned to do with Kamron before she met Cook and made plans to go to the house in DC.

“If the novelty wore off or she realized word got out that he was missing,” says Captain Dawson, “what would have happened then?”

Lanashia Wells walked through the halls of the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children and saw photos of kids who’d gone missing when they were Kamron’s age.

The center keeps every case open until a child, or a body, is recovered. Forensic artists create age-progression renderings of missing children to illustrate what they might look like 5, 10, 20 years later. The kids grow up on a computer screen, one artist says. A girl who’d been missing 15 years, after being abducted by her mother, identified herself from an age-progression photo on a bulletin board at Walmart.

Before Wells’s son disappeared, she’d never paid attention to Amber Alerts or the missing-children fliers in the mail. She didn’t realize so many families were waiting for answers. I’m so lucky, she thought.

She didn’t follow the case against Falah Joe, who was found not guilty by reason of insanity and sentenced to time in a mental-health facility.

“I didn’t kidnap no one!” Joe yelled during a hearing. “The little boy was outside in the cold by himself!”

It would have been different if Joe had hurt Kamron, Wells says, but he came back the same boy he was when she’d left that morning. He played outside the next day.

“It’s like if a kid goes out on a bike and falls and scrapes his knee,” she says. “If you see it but don’t see it, he’s more inclined to wipe it off—but if you run to him crying, it brings out emotions that maybe he could have kept under control.”

On a recent Saturday, Kamron is hanging out in his living room, waiting to make himself a peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwich and showing off the medal he got for his bravery.

“I said, ‘You’re not my mom.’ That was the bravest part, ” he says. “Then the police showed up.”

He received the award at NCMEC’s Congressional Breakfast, where he got to meet John Walsh. Kamron wants to take the medal to class with him because he changed schools last year—the family moved to a gated community in Burke—and his friends haven’t seen it. He’s eager to talk about the time he “got lost”—his mom says he likes the attention.

“You never got lost—you were tooken,” his sister, Tylah, says. For a while, the nine-year-old blamed herself for not staying with her brother in the aisles. She was carrying the milk that day and it was too cold, so she wanted to put it in a cart.

“We were going to Shoppers, then I was by the ice-cream shop,” Kamron says. “Then this lady came by. We walked all the way to her house.”

“Don’t you know how to scream?” Tylah asks. “If that was me, I’d scream. Mom, if somebody tried to take me, can I punch them?”

“You can do whatever it takes to get away,” she says.

Kamron is seven now, starting second grade, and really into dodge ball and Nintendo. He remembers that the house he and Joe went to was shaped like a square and that the couch he sat on was a peach color. There was a big-screen television, and the lady let him watch cartoons. At one point, he saw her kiss her boyfriend, so he looked away. His tummy growled.

“She didn’t ask me to come with her—she just took me,” he says. “I thought I would never see you guys again.”

This story appears in the September 2010 issue of The Washingtonian.