As the Redskins wind down another disappointing season, many fans are hoping for a better showing next year. But DeMaurice Smith, who heads the NFL Players Association—the Washington-based union that represents pro football players—is touring the country with an unsettling outlook: Unless the fight between players and team owners is resolved, there won’t be a 2011 season.

In a time of nearly 10-percent unemployment, it’s tough to find sympathy for millionaire wide receivers. So Smith has enlisted powerful labor unions to help spread the word that an NFL lockout—or work stoppage—isn’t going to hurt just Santana Moss. Stadium workers, restaurant owners, parking attendants, and others will also be hit.

On a recent night, Smith appears before an audience of beer-drinking Steelers fans in a Pittsburgh sports bar. After United Steelworkers and AFL-CIO officials make their point—“We stand with the players”—Smith introduces Steelers safety Ryan Clark, lineman Max Starks, and quarterback Charlie Batch.

“I am proud to be in union country,” he tells the crowd of black-and-gold jerseys and Teamsters jackets. The Players Association represents about 1,900 athletes. But the unions it has partnered with have 44 million members. And hooking up with Big Labor is just one of the strategies Smith is pursuing.

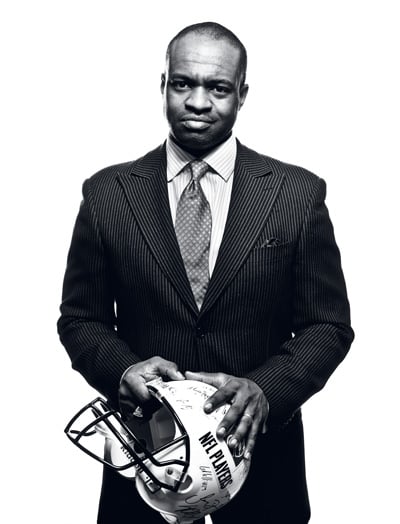

Wearing a sharp gray suit and white dress shirt, Smith—who goes by “De”—works the crowd with the ease of a politician. At 46, he’s confident and energetic—shaking hands with union officials, smiling at Steelers players, chatting with fans. It’s not until he steps into the back seat of his chauffeur-driven sedan to return to his hotel that he betrays the downside of one of the highest-profile jobs in sports business—all those flights to and from the West Coast, the days away from his wife and two children in Bethesda, the weight of the 2011 NFL season.

From the moment he was elected head of the Players Association in March 2009, Smith has faced challenges on all fronts. After succeeding the legendary Gene Upshaw—the Oakland Raiders Hall of Famer who died in 2008—Smith had to establish himself as a credible leader despite his lack of experience in pro football. He was criticized for failing to take care of retired players. But the most pressing concern was the labor dispute.

In 2008, the league’s 32 owners decided they had gotten a lousy deal in their 2006 labor agreement, and they exercised their right to opt out. Owners complained that while NFL revenues jumped to $7.8 billion in 2010 from $4.8 billion in 2005, profit margins were being squeezed by stadium construction costs and rising player salaries. They argued that while players benefited from the investments by owners—in stadiums, the NFL Network, and NFL.com—the owners were stuck with the tab. So the owners are asking for another $1.3 billion of league revenues before players get their portion. (After owners take a cut for expenses, NFL revenue is divided roughly 60/40 between players and owners.) They also want two more regular-season games and a cap on rookie salaries.

The players see the proposal as an 18-percent pay cut and have asked the owners to show that they’re facing financial pressures by handing over the books. The owners have refused. If a new deal isn’t reached by the time the current agreement expires in March, the owners are expected to lock out the players.

Although Upshaw—Smith’s predecessor—was revered for engineering nearly two decades of labor peace, his players union was a “meat-and-potatoes, handshake kind of place” that operated anonymously from its headquarters in downtown DC, says Roman Oben, a 12-year NFL veteran and former union player representative. The players spent just $60,000 on lobbyists in 2006, while NFL owners spent $740,000.

Smith came to the union from Patton Boggs, where he was a litigation partner and chair of the firm’s government-investigations unit. He served on President Obama’s transition team after nearly a decade at the US Attorney’s Office for DC and a stint as counsel to then deputy attorney general Eric Holder.

Under Smith, the players’ lobbying budget has ballooned to $340,000 in the first nine months of the year. Union representatives have met with nearly three-quarters of all members of Congress to share their message that an NFL lockout would mean angry constituents, roughly 150,000 job losses for stadium workers, and collateral damage to local economies. Meanwhile, the players union has hired inside-the-Beltway media strategists to raise public awareness of a potential work stoppage. The goal is to put enough pressure on the league to prevent the lockout.

Smith’s ties to Washington are more than professional. He was born in DC and raised in a strict Baptist household in Glenarden in Prince George’s County. His father, the son of a sharecropper and preacher, served in the Marines and spent 30 years as an accountant. His mother, a nurse, worked for the National Institutes of Health. “At the end of the day, education was important,” Smith says. “Community service was important. Family was important. And taking stands was important.”

At Riverdale Baptist High School, Smith ran track, played football, and served on the student council. Although never a star, he was the kind of football player coaches love. “He’s a guy you want on your team because his enthusiasm and attitude carries on to the other players,” says Jim Beckett, Smith’s high-school football coach.

Smith’s interest in the law was sparked in junior high, when the case of Terrence Johnson—a black teen who killed two white Prince George’s County policemen in 1978 amid disputed circumstances—polarized his racially diverse community.

“It seemed to me like the courtroom was kind of a cool place to fight,” Smith says. But it was his interest in the ministry that took him to Cedarville University, a small Baptist college in Ohio.

Smith was a sprinter in college but blew out his knee during his freshman year and went home to recover. When the cast was removed, the sight of his leg—which had withered to the size of his arm—brought him to tears.

“It would have been really easy for him to give up,” says Elvin King, Smith’s track coach at Cedarville. “But he was determined to come back and run again.”

Smith spent long hours in the weight room, returned to the track, and won the National Christian College Athletic Association championship in the 100-meter dash.

During his senior year, he became the university’s first African-American student-council president. Instead of entering the ministry, Smith settled on a legal career. He graduated from the University of Virginia School of Law in 1989.

After Upshaw’s death in 2008, the union conducted a nationwide search for his successor. When the Players Association initially contacted Smith, he asked if they were sure they had the right guy. Yet the lifelong Redskins fan believed he could make a difference at the union. As a trial lawyer, he first gathered a team of experts—antitrust lawyers, economists, corporate executives—to help him examine the business of pro football.

The search committee, composed primarily of active NFL players, was impressed. “He understood us better than some of our members did and presented viable options to solve every one of our problems,” says Kevin Mawae, a former Tennessee Titans lineman and current president of the Players Association.

Smith was a long shot to win the election when he arrived in Hawaii for the union’s annual meeting in March 2009. Former players Troy Vincent and Trace Armstrong had emerged as front-runners. In presentations to players, Smith argued that his legal background made him the best candidate. Lawyers, not players, were already running the unions representing pro athletes in basketball, hockey, and baseball. Underscoring his experience as a Washington insider and trial lawyer, Smith presented a plan to address the labor dispute by garnering support on Capitol Hill, reinvigorating alliances with unions, and developing a litigation strategy. He was elected on the first ballot.

“Guys, let’s get to work,” he told the players.

Smith has been credited with reaching out to retired players, but his efforts on Capitol Hill have drawn criticism.

Marc Ganis, a sports-business consultant who has worked with NFL teams on stadium deals, says it’s “unbelievably dumb” to involve Congress in the labor dispute because grandstanding lawmakers might turn their attention to issues the union would rather avoid, such as performance-enhancing drugs.

“DeMaurice Smith campaigned for his position as a Washington insider and has worked very hard to get Congress, the AFL-CIO, the White House, and others involved in our collective-bargaining issues,” says Jeff Miller, the NFL’s lobbyist. “We believe it would be far more productive for the union to devote more time to reaching an agreement.”

For his part, Smith argues that because lawmakers have granted the league “gifts” in the form of antitrust exemptions and nonprofit status, Congress is involved in the business whether it likes it or not.

“It’s not an issue of us wanting Congress to come in and do anything,” Smith says. “The gifts that the NFL is given from the Hill come with oversight, and what we are doing is asking those people to exercise the oversight responsibilities that they have.”

But the dispute is more likely to be resolved in court than in Congress. While the NFL’s antitrust exemption shields it from union lawsuits, the Players Association has the option to decertify its union status, a legal maneuver that would allow individual players to take the league to court to prevent a lockout. (The NFL could sue to block decertification.) The association decertified in 1989 and retrieved its union status in 1993, after reaching a deal with the league that allowed for free agency. All 32 teams have authorized the Players Association to decertify in the event of a lockout.

The pressure on Smith is immense. If he gives away too much at the bargaining table, his tenure will be short. But in leading the players union into the modern age, Smith has already ensured his legacy as the Players Association’s top man in Washington. A 2011 NFL season would be nice, too.

This article first appeared in the January 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.

Subscribe to Washingtonian

Follow Washingtonian on Twitter

More>> Capital Comment Blog | News & Politics | Party Photos

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)