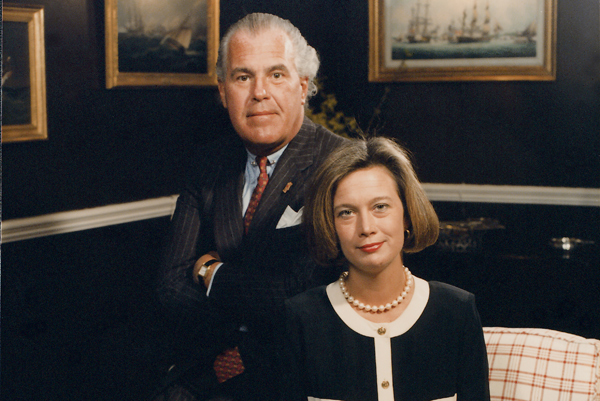

"Life with Howard was a big step up," the author says of her late husband. "It taught me that having money was better."

Looking back, I’ve always called it “the morning of the lawyers.” Like so many twists and turns in my life after my husband, Howard, died suddenly of pneumonia, it seemed benign at the outset.

His accountant said, “You need to call Howard’s lawyers,” and I took that as just another bureaucratic hurdle I had to jump in settling my husband’s estate. My focus was on shoring up whatever needed to be done to protect my son and me and to get Nathans—the saloon in Georgetown that Howard had owned since 1969—sold as quickly as possible. I wanted all the loose ends tied up, some money in the bank, and then a period to grieve and figure out the rest of our lives.

I’d grown up middle class in a military/academic family with little money to spare. From age 18 until I met Howard when I was 26, I’d earned my own way, modestly but comfortably. Life with Howard was a big step up, and it taught me that having money was better. Money bought good schools, good doctors, restful vacations, beautiful homes, excellent services, and a world of agreeable people who more often than not enjoyed similarly comfortable lives. I might be a widow now, but at least my five-year-old son, Spencer, and I would have enough money.

That morning in February 1997, like all the others since Howard’s death two weeks before, I moved from sleep to the wakeful haze of grief. I got up, ran, made breakfast, got Spencer off to school, and prepared to face the day.

I dressed for my meeting like an actress preparing for a role—the role of Howard’s widow. I did it for his sake. He had always been particular, and I wanted him to approve of my appearance. I wore my best black suit and shoes and my most discreet jewelry. The only thing missing was a black veil.

The offices of Caplin & Drysdale are in an impressive building on DC’s Thomas Circle. The firm specializes in tax law and is named for heavy hitters Mortimer Caplin, a former commissioner of the IRS, and Douglas Drysdale, a tax lawyer with more than four decades of experience.

I stepped off the elevator. There was a wash of cool gray in the walls, the carpet, the furniture, and the mood. The receptionist invited me to take a seat. “I’ll let them know you’re here, Mrs. Joynt,” she said.

I sat on a gray sofa, handbag in lap, and stared into the middle distance. The experience was new to me, and a little unsettling. Lawyers, contracts, business matters—these were all things Howard had handled on his own. My meeting today, I assumed, would be a formality. The lawyers would offer their condolences, maybe have me sign some documents, wish me well, and send me on my way.

Next: The case is now your responsibility. You are the defendant.

Not quite. Howard’s accountant, Martin Gray, had said it was urgent that I attend the meeting. And then there was something Howard had said over dinner sometime in the previous year. He mentioned a tax audit: “I won’t bother you with the details, and I’m not really supposed to talk about it. But you don’t need to worry. It’s bad, but I have a plan.”

The statement was unremarkable because whenever Howard mentioned audits—not uncommon with small businesses—they were nothing more than 24-hour storm clouds that always passed. When Howard told me not to worry about something, that he had a plan, I didn’t think any more about it.

“Hello, Carol.” An attractive woman walked toward me wearing a silk blouse with a bow at the neck and a straight skirt. She introduced herself as Julie Davis, one of Howard’s lawyers. She ushered me down a hall and into a conference room. When I walked in, all I saw was the large, dark table. It reminded me of the first time I walked into a bedroom with a man and all I saw was the bed. I took a deep breath to relax.

Several men stood around the table. Only one wore a tie, and that was Martin, the accountant. One by one, the men introduced themselves. There was a moment of almost Japanese politeness as we nodded toward one another. The men offered their condolences, hoped Spencer and I were doing well, and said they knew this was a hard time for us. “We don’t always dress this way,” one of them added. He explained that it was “casual Friday.”

It was difficult to comprehend the trouble Howard was in. I felt as if

I were in a slow-motion car crash.

Because I was meeting with Howard’s lawyers, I let myself believe they would be acting toward me on his behalf. So although I had approached this meeting with anxiety, I’d also expected it would be like visiting friends. The lawyers, as Howard’s surrogates, would wrap their arms around me and make me feel safe.

That wasn’t how it happened. All of the men—and the woman—squared their shoulders, adjusted the papers in front of them, and fixed their eyes on me. The needle on my fight-or-flight instinct suddenly moved to flight.

Cono Namorato, the lead lawyer, spoke first. He said that when Howard died, he was under investigation for federal criminal tax fraud and that the case against him covered both our personal taxes and the taxes of the business. As Mr. Namorato detailed Howard’s legal transgressions, I nodded as if I understood what he was talking about. Here was this tax lawyer with a sculpted face and a crisp manner telling me my husband was under investigation for tax fraud. What happened to the simple audit Howard had mentioned? What happened to the warm arms of lawyerly love? And why was it taking so long to get to the part where I signed whatever documents I had to sign so I could leave?

“Of course, as his will is written, with you as the sole heir, the case is now your responsibility,” Mr. Namorato said. “You are the defendant.” I froze. It was difficult to comprehend the trouble Howard was in but impossible to absorb that his mess was now mine. I felt as if I were in a slow-motion car crash.

Next: "What happens if I can't pay?"

“At one point, we were afraid Howard would be indicted,” said Mr. Namorato, who’d been a criminal-tax-enforcement official at the Justice Department. “But we were able to clear that up. They didn’t have a strong enough case for a criminal indictment.”

My throat went dry. I kept hoping Howard would walk through the door and tell me everything would be okay.

“Did Howard know that?” I asked.

“Yes.” Mr. Namorato folded his hands on the papers in front of him. “That was decided before the end of the year.”

“Then does that mean the case is closed?”

“No. We got rid of the criminal charges, but we’ve got a long way to go. There’s still the debt and the penalties. This case is attractive to the IRS because it’s a big number.”

My voice was thin and barely audible. “Big number? What does that mean?”

“We don’t know the final number, but it’s large.”

“How large?”

“In the millions. We don’t yet know how many.”

I had the same sinking feeling I’d had in the intensive-care unit at Sibley Hospital. There I’d learned I could lose my husband. Here I was being told I could lose everything else. I had nowhere to turn. I was on my own.

“Sell everything,” one of the lawyers said with such gusto that I wanted to grab a tire iron and whack him. I didn’t have that option at hand, but the anger helped quell the panic. “Pay the debt and get this behind you.”

“If I sold every last thing—and I mean everything—home, apartment, the boat, the cars, books, clothes, art, toys, knickknacks, and my wedding ring—I wouldn’t be able to come up with millions of dollars,” I said.

“Where’s the money?” Mr. Casual Friday asked me, as if I’d robbed a bank and stashed the goods.

“What do you mean where’s the money?” The needle on my fight-or-flight gauge was now moving toward fight.

“There must be money somewhere,” he said. “He had to do something with the money. Is it in offshore accounts?”

Offshore accounts? These people were his lawyers, for God’s sake. Wouldn’t they have known if there were offshore accounts?

“Howard didn’t hide money,” I said. “He spent it. He liked to spread it around. He didn’t want his money stashed on an island somewhere. He wanted it close and available.” The room was suddenly quiet.

I finally worked up the courage to ask the question: “What happens if I can’t pay?”

That got everyone’s attention. It was clear they’d never considered that possibility. They looked at one another and then back at me. I could hear the hum of the ventilating system. Martin Gray tapped his pen on the table. Someone cleared his throat. Finally Julie broke the silence. “Well, you could go for ‘innocent spouse.’ ”

“What’s ‘innocent spouse’?” I asked.

“It’s a code in the tax law that’s designed for cases where a spouse who has committed, say, fraud dies, but the surviving spouse doesn’t know anything about the fraud. The spouse can be declared innocent. When that status is awarded, the spouse is absolved of responsibility for the debt.”

That’s it! Thank God—that’s the solution. Before I could open my mouth, Julie added, “But you wouldn’t qualify.”

“What? Why not? I am innocent.”

“Because . . . .” She paused, gathered her breath, then poured out in a rush: “You had to know. How could you not know? Look at you!”

Look at me? Look at me? I wrapped my arms around myself. I could feel the fabric of my expensive black suit, but I felt naked.

“I didn’t know,” I said. “The only thing Howard told me was he was being audited and that the lawyers told him not to talk to me about it. So he didn’t. You were his lawyers. You must have told him that.”

They nodded but offered nothing else. I felt that in their eyes I was as guilty as my husband. Mr. Namorato said they would have better information in a couple of weeks when we would reconvene. In the meantime, I should start to get my house in order.

Next: The IRS agent's report read like the tabloid profile of a frivolous, spendthrift airhead.

I walked out of the building back onto the same street and the same daylight that were there when I arrived, but everything was different. The numbing fog of widow’s grief that had been present when I’d gotten up and dressed that morning was gone, replaced by fear. My hands shook. Before starting the car, I had to take a few deep breaths to calm down, to focus. For the first time in my life, I felt trapped.

And Howard, the person I’d always gone to, who would listen and understand and give me good advice and protect me, was gone, too. The irony that the man responsible for this mess was the same man I yearned to run to didn’t hit me then, but it did soon enough.

The IRS agent on the case was a woman named Deborah Martin. “She’s a junior agent,” Mr. Namorato said. “That’s why she’s so eager to get a big dollar amount. This is huge for her.”

Deborah Martin submitted her report on April 16, 1997, the day I returned to the lawyers’ office. I knew the damage done by my earlier appearance—the widow in the Chanel suit—had only emphasized the image of me as a coconspirator in a tax fraud, the client who “had to know.” This time, I was the one who dressed casually.

Deborah Martin, I was surprised to discover, was not present. When I asked about meeting her, Cono Namorato’s response was swift: “No. We’ll keep you away from her. No contact. That’s what we’re here for.”

It was clear my lawyers viewed me as the person Deborah Martin described in the opening of her report. I was a woman living a “lavish” and “luxe” lifestyle. It didn’t matter that I hadn’t known we couldn’t afford the life we lived. I drove a Range Rover. Yes, I drove it. Still did. In fact, it was parked outside. I also had a weekday live-in babysitter and a weekend babysitter who doubled as a housekeeper. I had a demanding job as a producer for Larry King Live, for God’s sake. And when we had a big dinner party, I hired a cook who worked for a catering company. I thought we could afford it.

And so it went. Deborah Martin’s report read like the tabloid profile of a frivolous, spendthrift airhead. Everything she wrote was technically true, although highly embellished. It documented every dime Howard had spent in the past five years. All of his credit-card charges, all of the checks, money he’d deposited, all of his investments.

You Might Also Like:

Carol Ross Joynt Book Signing (Pictures)

According to Martin’s report, when I wasn’t off on a luxurious holiday aboard a private jet or yacht, I sunbathed by the pool at my “estate” on the Chesapeake Bay while relying on my domestic staff to attend to my needs. That wasn’t how I saw my life, but it was how a young IRS agent chose to describe it. I’d thought we were living within our means. I hadn’t been the one paying the bills. I hadn’t known Howard couldn’t pay for the life we were living. My protests either didn’t register with my lawyers or simply sounded lame to them.

Martin’s report explained how Howard had run his expenses through Nathans and operated the business at a loss. Essentially the only income reported was mine, which created a discrepancy of at least several hundred thousand dollars. While Howard withheld about $200,000 in federal taxes from his employees’ paychecks, he didn’t send that to the government. He kept it for himself, for Nathans, and for some favored employees.

As I continued reading, each page felt heavier. When I got to the part where it detailed that my husband had written off the live-in babysitter’s wages as “trash collection” and some of his Christmas presents to me as “uniforms,” I stopped reading. I had reached my threshold of humiliation, embarrassment, shame, and guilt—and before an audience, too. Deborah Martin had caught a man who had broken the law, who’d committed tax fraud against the US government. It was as simple as that. The crook was my husband. It didn’t matter that he was ashes. The government wanted its money, and because dead people don’t write checks, I would be the one to pay. I was the defendant.

Next: The total was a breath shy of $3 million

Mr. Namorato slid a single sheet of paper across the polished table. It broke down what was owed. The debt to the feds came to almost $2.5 million, and the meter on interest and penalties was running. The total was a breath shy of $3 million, an amount incomprehensible to me. Amounts owed to the District of Columbia and Maryland hadn’t yet been calculated. I stared at the numbers as the lawyers and accountant talked about my options. My inner voice begged: Don’t cry, don’t cry, not here, please don’t cry, not here, don’t cry, don’t cry.

“Well, she still has the issue of the promissory note.”

“We’re going to have to comb through that, but I don’t think it will fly.”

“The withholding is the big issue, and that’s where most of the debt is.”

“But we can try to flip that one issue with another.”

“No, it won’t work.”

“I think we go back to Deborah and ask for some backup on a few of these numbers.”

“At least Carol has her job at CNN. That looks good.”

“You can’t take this into a courtroom. It’s a slam-dunk against her.”

They debated while I sat there, invisible. No one asked my opinion. As the shock of the numbers wore off and I began to tune in to the lawyers’ words, something inside me clicked.

“Wait!” I said. “Stop! Listen to me.” All eyes shifted. “I don’t understand any of this.” I gestured at the documents on the table, the pages of evidence, the numbers that totaled up the debt. “And I don’t understand half of what you’re saying.”

I looked from one lawyer to the next. “Doesn’t anybody understand that I didn’t do this?” I said. “They’ve got the wrong person. The person who did this is dead! This is all news to me. I found out only two weeks ago that we even have mortgages. There wasn’t anything about our lives that struck me as inappropriate. Yes, we lived well, but it wasn’t outrageous, it wasn’t ridiculous, it wasn’t gross and over the top. My husband had a successful business. He had an inheritance. It all made sense to me.”

I continued to fight back the tears. The last thing I wanted was to let these people see me crumble.

“I don’t know what Howard did,” I said. “I hope that whatever it was, he didn’t do it on purpose, that it was a mistake. But I can’t ask him. He’s not here. I do know this: I didn’t do it, and my son didn’t do it. I’m innocent.”

Next: Grief will have to wait.

There was silence. Finally, Mr. Namorato spoke up. “But you signed the tax returns.”

“I know, but they were filled out by an accountant.” I looked at the accountant, who looked away. “Why wouldn’t I sign them?”

Martin Gray shifted in his seat and cleared his throat. “I was working with the numbers Howard provided me,” he said.

“So was I!”

“We’ve got a long way to go,” Mr. Namorato said, trying to calm me down.

“What happens now?” I asked.

“We’ll talk to Deborah Martin,” Julie said. “They can put liens on your accounts. We’ll try to stop that. You should find out how much you can come up with. What if you sell your house? What will you get for that? And the art? You have a lot of antiques, right? What would that add up to?”

“My house? Just sell it?”

“That’s one way of paying this off,” someone said.

“I want to keep my house.” It was our safe harbor. It was my little boy’s home.

“What about the life insurance?” one of the lawyers asked.

“There is no life insurance,” I said.

“What? How can that be?”

“Howard didn’t believe in life insurance. I only got him to sign a will a year ago. He didn’t want to do it because he thought it would jinx him, that he would die.” I smiled weakly at the irony. “It looks like he was right.”

That was that. The meeting ended with a refrain of “We’ll make some calls and get back to you. We’ll meet again next week.”

Mr. Namorato wrapped his arm around my shoulder and walked me to the elevator. “Now, Carol,” he said, “don’t leave here depressed.”

Was he crazy? All of my worst fears had come true. Spencer and I were going to lose everything. Our lives would be ruined. I was beyond depressed.

That night I had a fitful sleep, but the fact that I slept at all was probably the bigger surprise. What kept me awake was not simply the perplexing bad deeds my beloved husband had done but the sheer magnitude of what had landed on us. There was my frightening ignorance of this dangerous new world of cash flows and taxes, criminal fraud and lawyers. I had to get sophisticated fast. Grief, I knew, would have to wait. Tears could come later. First, I had to save us.

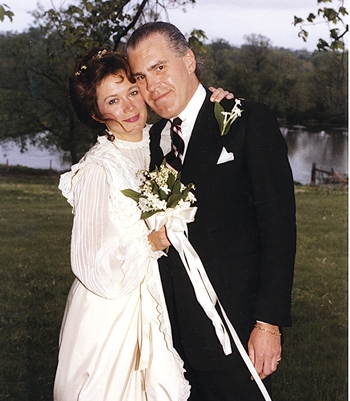

This article appears in the May 2011 issue of The Washingtonian. "Innocent Spouse" was published in May, 2011 by Crown, and is available from Amazon and other major retailers.