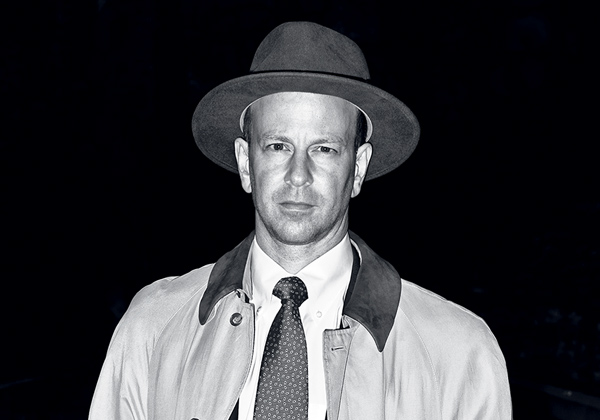

Photograph by Chris Leaman

David Kris was the United States’ top lawyer on counterterrorism and espionage for the first two years of the Obama administration, overseeing some of the nation’s biggest cases: “underwear bomber” Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, the Times Square bomber, and the ring of Russian spies captured in the summer of 2010.

He became a government lawyer years before the 9/11 attacks, but the war on terror turned into the defining theme of his career. He left government in 2003, worked in private practice, and then returned in 2009 to run a new national-security division at the Justice Department that he had a hand in creating.

Kris, 44, graduated from Haverford College and earned his law degree at Harvard. He’s married with two children, ages ten and seven. A few weeks after leaving his post in March for a new job in Seattle, he sat down to talk about whether America is safer from terrorist attack, why the country’s legal system is still the envy of the world, and what he’ll miss most about life in Washington.

You came into the Justice Department before the 9/11 terrorist attacks, when terrorism wasn’t as high-profile a calling for an attorney. How did you get into this line of work?

I stumbled into it. In 2000, I’d been at Justice eight or nine years as a prosecutor, doing ordinary criminal-law trials and appeals. It was near the end of the Clinton administration. Normally there are vacancies at the end of an administration. So in the spring of 2000, I was asked out of the blue whether I’d be interested in being an associate deputy attorney general. You know, in Washington, the more words that are in your title, the less important it is.

My initial thought was under no circumstances would I be interested. I was a lawyer, and I thought I wouldn’t enjoy working in a bureaucratic environment. But after taking counsel from a number of friends and advisers, I decided I could safely take that job on a temporary detail.

But then when I started to develop the expertise and acquired the security clearances to do national-security work, there was a momentum effect. And I found that I just kept doing this kind of law because I’d already been doing it.

But was there something about these cases that made you want to stick with them?

To me it’s the part of law where the stakes are highest on both sides—for the government and for civil liberties. One of the reasons I went into law as opposed to philosophy, which is what I studied in college, is I wanted to engage in debate and reasoning in a way that had a profound impact. You can do that in national security.

You obviously had no idea what was ahead for you. Just a little more than a year into the job, 9/11 happened.

That was not a good day for anybody. As I recall, the attorney general, John Ashcroft, was out of town. The deputy attorney general, Larry Thompson, was in the department headquarters building. When the attacks occurred, he and certain others went to an off-site location. Most of the department was evacuated. But there was a need to leave some people behind in the Justice Department’s command center so we’d have some redundancy. And I was one of the relatively small group to stay behind.

I have a vivid recollection of just concluding, or sort of knowing in some kind of elemental way, that we’d surely be dead by lunchtime, because one of the next planes that would strike would be aimed at either us or the FBI building or both.

At one point I stepped out to telephone my wife and say goodbye to her. In a strange way, I just dealt with the events, which were overwhelming on a minute-by-minute basis, rather than thinking big thoughts.

You stayed in the government until 2003, then you spent six years as an attorney in the private sector. What drew you back to this new job as head of the National Security Division, which was established while you were out of government?

Most of the jobs I’ve had have been unplanned. But this is an exception. I was involved in establishing what I consider to be its legal underpinnings. In 2002, I worked on the case before a special surveillance court that dealt with how intelligence and law-enforcement agencies could share information about terrorism and espionage cases. The so-called wall that existed between those groups came down after that case, and that led directly to the creation of the National Security Division. When I had an opportunity to lead the division, I was very eager to do it.

I worked harder in this job than I did after 9/11. I didn’t think that would be possible. There was more for me to do, but it wasn’t as emotionally challenging as the immediate aftermath of 9/11.

What achievement are you proudest of?

The division really developed in a way that I think makes sense: taking down the wall and encouraging cooperation between people who employ different disciplines—intelligence and law enforcement—but who have a common mission of protecting against the threats of terrorism and espionage.

It’s very similar to the idea that underlay the creation of the Civil Rights Division. It didn’t matter back then whether you were protecting civil rights by criminal law enforcement or through civil litigation. The key was that you were pursuing civil rights, which at the time was arguably the Justice Department’s highest priority.

Is the United States safer from terrorist attacks today than it was on 9/11? And how do you measure that? The past two years have seen a dramatic increase in the number of attacks attempted on US soil, and some of them nearly succeeded.

It’s a difficult question because the threat we’re facing has evolved in a substantial way. In some ways it’s more dangerous and in others less. The period from spring of 2009 through 2010 was enormously intense. The statistics paint a very dramatic picture. We have first a proliferation of terrorist nodes. It used to be that al-Qaeda in the tribal regions of Pakistan was the key. Now we see al-Qaeda in Yemen and al-Shabab and affiliate elements in the Horn of Africa.

You also have increased use of the Internet, spreading the word of jihad without respect to geographic boundaries. That contributes to radicalization.

But some terrorist operatives are not as well trained and as commanded as before 9/11. That means they’re going to be less likely to be sophisticated or successful. On the other hand, there may be fewer opportunities for us to pick up on instructions being relayed from known terrorist sources, which means they may be harder to detect.

Next: Controversial interrogation tactics and what the law taught Kris about life

Are we safer than we were ten years ago?

In some ways we definitely are. The government is without any doubt much better at protecting against terrorism and preventing attacks—better than it was in 2003, when I first left government. We have learned. But the adversary has also learned and changed. So it’s a constant challenge to keep up. On the one hand, we’re safer because our systems are better. On the other hand, the threat is changing day to day.

Do you think the American legal system has been damaged by our government’s response to 9/11 and to terrorism?

One of the strengths of the system is its resiliency. I think it is rightly the envy of the world, or certainly admired around the world.

But you’ve been a critic of it, too. Before you came back to the government, you wrote a rather famous paper about the Bush administration’s once-secret program of warrantless electronic surveillance, which had recently been exposed by the New York Times. You didn’t know about this program’s existence when you were in government, but given what an authority you are on national-security law, a lot of people read this paper as a broad critique of the Bush administration’s expansive views of presidential power in the war on terror.

I wrote a technically narrow report about the President’s surveillance program, and I reached the conclusion that it violated the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, the statute that governs when the government can and cannot monitor suspected terrorists or spies. I didn’t evaluate the constitutional issues.

But when you wrote your paper, yes, it was critiquing a mind-numbing statute that few people other than you deeply understand, but you pointed to a much larger issue: the great mistrust that people had of their government, that it wasn’t following the rules. The public interest in that wasn’t narrow. So I think you’re in a much better position to evaluate the legal system as a whole than you seem to be giving yourself credit for.

I tried in this job to make some space to invest in thinking about how we can improve the system. Because otherwise everyone’s just dealing with today’s emergency and suffering from the tyranny of the in box. But I do think the system is in pretty good shape.

One systemic concern I have is that we sometimes make policy judgments from 30,000 feet, based almost on aesthetic judgments, without giving enough attention to the actual operational questions. For example, we may limit our responses to terrorism because of some abstract belief rather than looking at the ground truth—what do we face, what is the threat?—and then working up from there to the policy. I worry we haven’t paid enough attention to the ground truth. If you accept that we’re in a war—and I do—and the goal is to win, then you have to ask yourself: What tools do I have at my disposal? There are some things we’re not going to do.

Like what?

Waterboarding is the most famous. There are some people today who’d say today they support that. I think former Vice President Cheney is one. Some people say no. But you can go down the continuum, even toward the medieval, and someone somewhere is going to say no, there are some tactics we simply will not employ.

You want to make sure that the people closest to a threat operationally have the tool to deal with it. Where the threat looks like a nail, the right tool is a hammer. Where it’s a bolt, the right tool is a wrench. But if policymakers say we’re going to tell you only to use a hammer, that doesn’t work. I believe that’s not the right way to think about it, artificially limiting the tools that people on the ground can use legally.

I fear we’re losing sight of the way the threat environment should inform our policy choices. To really be smart about the policy choices, you have to understand how the tools work at an extremely granular level. That’s very challenging.

Do you think Article III criminal courts can handle terrorism cases?

In a speech I gave in June 2010 at Brookings, and in a law-review article that I hope will be coming out soon, I advanced the argument that in some cases, from the government’s perspective, prosecution in an Article III court is more effective in disrupting, incapacitating, and gathering intelligence from terrorists than either prosecution in a military commission or detention under the law of war. In other cases, of course, it will not be the most effective method. Given that, it makes no sense to me to adopt some blanket rule against using Article III. If we want to win the war, we need to use whatever methods, consistent with our values, that are most effective under the circumstances of a particular situation.

More From Shane Harris:

Is Bloomberg Government the Next Washington Media Death Star?

You’re leaving one Washington for another, moving to Seattle to be general counsel for Intellectual Ventures, where you’ll work a lot on patent law. What are you going to miss most and least about this Washington?

I’ve lived here 19 years. And the two years I spent at the National Security Division were the highlight of my career. But it does take its toll. I have two young children. Typically when people say, “I’m leaving government to spend more time with my family,” it’s code for “I have a drinking problem.” Fortunately, that’s not the case with me. But I certainly am looking forward to spending more time with my wife and children and not getting calls at 2 in the morning demanding that some decision be made. It will be nice to sleep through the night again.

What has the law taught you about life?

I studied philosophy in college, but I am glad to have gone into law because law matters so much—the rule of law makes such a big difference to so many people.

One of the things I have enjoyed about my career in the law is the variety of things I’ve been able to do—criminal law, national-security law, corporate and business law, and intellectual property. Each time I move into a new area, it’s daunting; but it’s also exciting and interesting.

Even when I am out of government, I haven’t been able to stay away from national-security law for too long—as a hobby if not a profession.

This article appears in the June 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.